The Chest Bump: Pulmonary Pearls & Pitfalls to Consider in Patients with Chest Trauma

- May 7th, 2018

- Mark M. Ramzy

- categories:

Authors: Mark M. Ramzy, DO, EMT-P (@MarkRamzyDO, EM Resident Physician, Drexel University, Department of Emergency Medicine) and Richard J. Hamilton, MD (EM Chair, Drexel University, Department of Emergency Medicine)// Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 39-year-old male presents to the emergency department with shortness of breath and chest pain. Patient states he was assaulted three days ago with a punch to the chest, he suffered no head trauma or loss of consciousness. He was evaluated at another hospital immediately following the assault where a chest x-ray was performed, he is unable to recall the results. He was subsequently discharged from that hospital. Today he describes his centrally located chest pain as non-radiating, sharp, and pleuritic. Pertinent positives on physical exam include the following: anxious-appearing African American male in mild distress. The breath sounds on the upper left chest are decreased. There is point tenderness over the left anterior and lateral chest wall. Vital signs: BP 118/75, HR 96, RR 24, SpO2 88% on room air.

This patient’s clinical presentation and history raise many questions. Several of the diagnoses that emergency physicians are concerned about can often be answered by a good history. Unfortunately, the above patient is not a very good historian, leaving us to rely on our physical exam findings and clinical judgement skills. This post will focus on both threatening and non-threatening pulmonary conditions that may arise from blunt trauma to the chest. Furthermore, it will provide pearls and pitfalls for each condition that will enhance your ability to evaluate a patient with blunt injury to the chest.

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures, though often minor, can be an indication of a potentially more serious internal injury with significant associated structural and vascular complications. When considering the diagnosis of rib fracture in a patient, think of the following pearls and pitfalls:

Pearls

- 50/50 Rule (part 1):50% of patients admitted to the hospital following chest trauma are diagnosed with rib fractures.

- Due to their short length, a considerable amount of force is required to fracture the first and second ribs.1

- If you’re having difficulty appreciating a lateral rib fracture on a chest x-ray (CXR), try rotating it 90° with the concerning side pointing upwards. Because this breaks up the usual chest radiograph pattern that your brain is accustomed to, your vision does a better job of “seeing” each rib as it is, rather than defaulting to a normal interpretation.

Case Continued

Following our exam, the patient was placed on 3 liters of oxygen via nasal cannula. His dyspnea continued, and his oxygen saturation only improved to 90% after 5 minutes. He was then switched to 10 liters of oxygen via non-rebreather. Given the shortness of breath and point tenderness over the left anterior and lateral chest wall, a chest x-ray was ordered and interpreted using some of the pearls above.

Pitfalls

- 50/50 Rule (part 2): Within the first few days following an injury, 50% of rib fractures are not seen on a CXR.2

- With multiple lower rib fractures, particularly ribs 9-12, it is important to consider intra-abdominal bleeding often from a liver or spleen laceration.

- Elderly patients with multiple rib fractures may have difficulty clearing secretions and should be closely monitored for airway compromise.

Pulmonary Contusion

Most commonly caused by significant blunt injury to the chest wall following high speed motor vehicle crashes, pulmonary contusions and their complications can be associated with severe mortality and morbidity. On exam, there may be significant external skin findings such as ecchymosis or the classic “seat belt” sign as well as decreased breath sounds over the affected area. When diagnosing a patient with a possible lung contusion, it is important to remember that contusions are typically located across non-segmental areas of the lung. Furthermore, the timing and progression of the injury can serve as helpful indicators as to which disease process is actually present.1

Pearls

- Computed tomography (CT) imaging is more sensitive for the detection of pulmonary contusions, however in most cases the contusion is an incidental finding.3

- A lung consolidation within 6 hours of blunt trauma lasting 48 to 72 hours is diagnostic for a pulmonary contusion.1

- “Good Lung Down”: mechanically ventilated patients are more susceptible to lung contusions, however improvements in ventilation-perfusion matching can be made by turning the patient in the lateral decubitus position so that the non-injured lung is now dependent or downwards pointing to the floor.4

Pitfalls

- Up to 70% of pulmonary contusions are not visible on the initial radiograph.6

- TIMING MATTERS: Pulmonary contusion on CXR may often initially be confused with aspiration, atelectasis, and/or infection but progress differently on radiographs.

Pneumomediastinum

Most commonly caused by blunt chest trauma resulting in alveolar rupture, air in the mediastinum is an injury that warrants a thorough history and physical exam. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum may also occur in non-traumatic patients and is usually a result of asthma, diabetic ketoacidosis, forceful straining during exercise, and inhalation of drugs or medications. The dissection of the bronchoalveolar sheath and spread of air into the mediastinum is known as the Macklin Effect.1,7

Pearls

- The presence of a crunching sound over the heart known as Hamman’s Sign or Hamman’s crunch is best heard in the left lateral position.

- Can be diagnosed on CXR, however it has been shown that CT is superior in diagnosing pneumomediastinum.

- Unless the patient is symptomatic, no additional imaging or intervention is necessary.8

Pitfalls

- Patients with these injuries may be asymptomatic or only have mild symptoms of cough or voice changes.

- Be sure to assess for subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and surrounding tissue.

- The Macklin effect has been frequently seen on CT images of patients with spontaneous pneumomediastinum not associated with trauma.7

Hemothorax

Most commonly caused by hemorrhage from intercostal or internal mammary arteries secondary to blunt and penetrating trauma, the accumulation of blood in the pleural space can quickly progress to hypovolemic shock if not appropriately managed. When dealing with blunt trauma patients, the presence of a flail chest or multiple rib fractures should raise serious concern for an underlying hemothorax. This is especially the case in tachypneic and tachycardic patients as they can quickly decompensate into a state of hemodynamic instability.1

Pearls

- Ultrasound has greater sensitivity than supine chest radiography in detection of hemothoraces.

- Should ultrasound be delayed or not immediately available, the diagnosis can be made with an upright Attempts should be made at obtaining imaging in this position just before or after transfer of the patient from ambulance stretcher to hospital bed.

- Costophrenic angle blunting secondary to hemothorax typically seen on CXR requires at least 200 to 300 mL of fluid to accumulate.10

Pitfalls

- Posterior accumulation of blood creates a diffuse infiltrate appearance that is often mistaken for a pulmonary contusion.

- A chest tube that is too small can result in obstruction, kinking, or inadequate evacuation of fluid. A 36 to 40 French should be inserted at the 5th intercostal space at the anterior axillary line to ensure adequate drainage of fluid.11

- Remember that initial drainage of 1500 mL of blood from the chest tube, or >200mL/hour over 2-4 hours, requires a thoracotomy.12,13

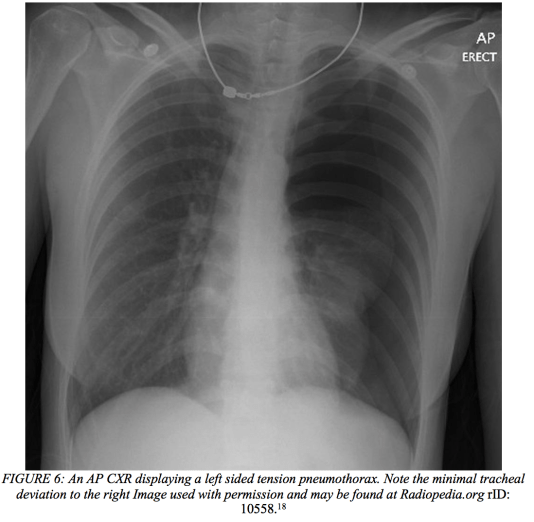

Tension Pneumothorax

Defined as the buildup of air within the already highly pressurized pleural cavity, this potentially fatal lung condition is characterized as a “tension pneumothorax” when it leads to a shift of mediastinal contents in the opposite direction. Furthermore, a patient who presents as hemodynamically unstable may a pneumothorax with underlying tension etiology due to various traumatic mechanisms. The circulatory consequences of this kind of anatomical movement can have devastating outcomes when not managed quickly and appropriately. The increase in intrapleural pressure from the accumulation of air, results in vena cava compression leading to dyspnea, agitation, hypotension, and cyanosis. These clinical symptoms are due to the cardiovascular compromise that occurs from decreased diastolic filling and decreased cardiac output.11

Pearls

- Ultrasound has been shown to have a greater sensitivity for identifying pneumothorax than CXR.14,15,16,17

- Chest tube placement should immediately follow the placement of a needle thoracostomy even if resolution of symptoms occurs.

- One of the earliest signs of a tension pneumothorax in a mechanically ventilated patient is resistance to manual ventilation when using a bag-valve mask.11

Pitfalls

- Placement of a needle thoracostomy at the lateral aspect of fourth or fifth intercostal space of the affected side is recommended as studies have shown that some catheters are not long enough to penetrate the pleural space in the second intercostal space.19

- Fractured ribs secondary to cardiopulmonary resuscitation may cause a tension pneumothorax and thus lead to hypoxia even when the patient is intubated and mechanically ventilated.

- Unlike a hemothorax, the signs and symptoms of a patient do not always correlate with the degree, timing, or duration of the pneumothorax.

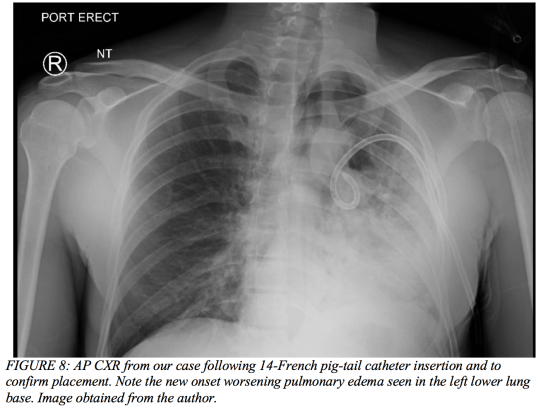

- Be aware of re-expansion pulmonary edema that typically occurs following chest tube placement. This is particularly the case in patients that may have had a small subacute asymptomatic pneumothorax for more than one or two days.1

When is imaging NEXUSsary?

Similar to the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Criteria, a NEXUS Chest Rule has been developed to help limit overutilization of imaging and radiation exposure in blunt trauma patients. A cohort study prospectively validated this decision instrument and found it to have a 98% sensitivity for predicting clinically significant intrathoracic injury in blunt trauma patients over the age of 14 years old.20 However, the criteria should only supplement clinical gestalt and decision making, rather than replace it.

Case Conclusion

After initial imaging displayed a pneumothorax (Figure 7 above), our 39-year-old male had a pig-tail catheter placed successfully (Figure 8 below). However, his dyspnea failed to improve, and he continued to desaturate even when connected to supplemental oxygen via non-rebreather. The decision was made to replace the pig-tail catheter for a 28-French chest tube (Figure 9). His clinical status failed to improve even after this intervention, and he ultimately required intubation due to impending respiratory failure and an evolving pulmonary contusion. The patient was then transferred to the surgical intensive care unit and closely monitored on mechanical ventilation for two weeks. His oxygenation and ventilation improved over time, and he was extubated and subsequently discharged without any further complications.

References / Further Reading

- Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Livingston DH, Shogan B, John P, Lavery RF: CT diagnosis of rib fractures and the prediction of acute respiratory failure. J Trauma64: 905, 2008

- Kaewlai R, Avery LL, Asrani AV, Novelline RA: Multidetector CT of blunt thoracic trauma. Radiographics28: 1555, 2008.

- Choe K, Kim Y, Shim T, Lim C, Lee S, Koh Y, et al. Closing volume influences the postural effect on oxygenation in unilateral lung disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2000;161(6):1957-62.

- Case courtesy of Dr Gagandeep Singh,

From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/7259″>rID: 7259</a> - Exadaktylos AK, Sclabas G, Schmid SW et al.: Do we really need routine computed tomographic scanning in the primary evaluation of blunt chest trauma in patients with “normal” chest radiograph? J Trauma51: 1173, 2001.

- Murayama S, Gibo S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and Macklin effect: Overview and appearance on computed tomography. World Journal of Radiology. 2014;6(11):850-854.

- Okada M, Adachi H, Shibuya Y, Ishikawa S, Hamabe Y. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Respir Investig. 2014;52:36–40.

- Case courtesy of Radswiki, From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/11793?iframe=true”>rID: 11793</a>

- Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al: International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: pp. 577-591

- Rosen, N. G., & Green, T. J. (2014). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (9th ed., pp. Chapter 38, 382-403.e2). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- Subcommittee A, American College of Surgeons’ Committee on T, International Awg. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS(R)): the ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1363-6.

- Mowery NT, Gunter OL, Collier BR, et al. Practice management guidelines for management of hemothorax and occult pneumothorax. J Trauma 2011; 70: pp. 510-518

- Volpicelli G: Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37: pp. 224-232

- Donmez H, Tokmak TT, Yildirim A et al. Should bedside sonography be used first to diagnose pneumothorax secondary to blunt trauma? J Clin Ultrasound 40: 142, 2012.

- Hyacinthe AC, Broux C, Francony G et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in the acute assessment of common thoracic lesions after trauma. Chest 141: 1177, 2012.

- Blaivas M, Lyon M, Duggal S: A prospective comparison of supine chest radiography and bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med

- Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard,

From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/10558″>rID: 10558</a> - Sanchez LD, Straszewski S, Saghir A, et al: Anterior versus lateral needle decompression of tension pneumothorax: comparison by computed tomography chest wall measurement. Acad Emerg Med 2011; 18: pp. 1022-1026

- Rodriguez RM, Anglin D, Langdorf MI, Baumann BM, Hendey GW, Bradley RN, Medak AJ, Raja AS, Juhn P, Fortman J, Mulkerin W, Mower WR. NEXUS Chest Validation of a Decision Instrument for Selective Chest Imaging in Blunt Trauma. JAMA Surg.2013;148(10):940–946.

One thought on “The Chest Bump: Pulmonary Pearls & Pitfalls to Consider in Patients with Chest Trauma”