EM@3AM: Serotonin Syndrome

- Mar 13th, 2021

- Andrea Nillas

- categories:

Author: Andrea Nillas, MD (EM Resident Physician, UTSW/Parkland Hospital) // Reviewed by: Kerollos Shaker, MD (Medical Toxicology Fellow, UT Southwestern Medical Center), Nancy Onisko, DO (Medical Toxicologist / EM Attending Physician, UT Southwestern Medical Center); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 40-year-old female with history of depression is brought in by EMS for agitation. On arrival she is confused and diaphoretic. Vitals include temperature of 40°C, BP 150/80, HR 120, and RR 28. Exam is remarkable for muscle rigidity, hyperreflexia, and clonus of the lower extremities.

What is the next step in your evaluation and treatment?

Answer: Serotonin syndrome

Epidemiology:

- Observed across all ages with increase in incidence attributed to increased use of pro-serotonergic agents, such as anti-depressants, in clinical practice [1, 2]

- Commonly implicated drugs:

- SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, MAO inhibitors (associated with most severe reactions), Lithium [3]

- Opiate analgesics (e.g. Fentanyl, Tramadol) are second most common

- Anti-emetics (e.g. Ondansetron, Metoclopramide)

- Antibiotics (e.g. Linezolid) [4]

- Antimigraine (e.g. Sumatriptan) [2]

- Over-the-counter cough and cold remedies: dextromethorphan [2]

- Drugs of abuse (e.g. MDMA [ecstasy], LSD, cocaine)

- St John’s Wort, methylene blue

- True incidence is unknown as it is under-recognized if symptoms are mild [5,6]

- Majority of documented cases occurred in patients taking therapeutic doses, but about 10% of cases develop after overdose [6]

Mechanism of Action:

- Serotonin (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter that has central and peripheral effects

- CNS: modulates attention, cognition, behavior, thermoregulation [1]

- PNS: GI motility, vasoconstriction, bronchoconstriction, platelet aggregation [1,7]

- Of the 7 subtypes of serotonin receptors, the two most implicated in serotonin syndrome are 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A[1]

- 5-HT1A subtype has higher affinity for serotonin than 5-HT2A When fully occupied, 5-HT1Alikely contributes to milder symptoms

- Higher concentrations activate 5-HT2A receptors leading to more severe symptoms

- Increased serotonin activity can result from increases in serotonin synthesis or release, direct serotonin receptor agonism, inhibition of serotonin re-uptake, or decreased serotonin metabolism (from monoamine oxidase inhibitors) [8]

Clinical Presentation:

- Clinical triad [1-3]

- Mental state changes [2]

- Anxiety, agitation, delirium, seizure, coma

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Hyperthermia, hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, flushing, mydriasis, N/V/D prodrome

- Neuromuscular abnormalities

- Hyperreflexia, clonus, myoclonus, tremor, hypertonia/rigidity

- Mental state changes [2]

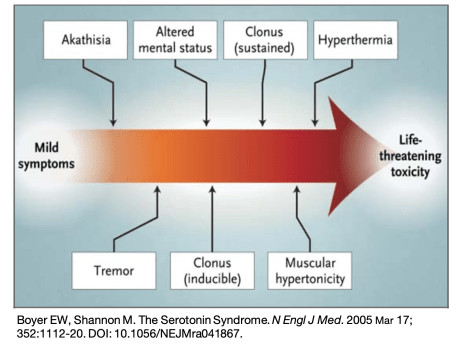

- Spectrum of findings from mild to severe [2]

- Mild- tachycardia, diaphoresis, mydriasis, intermittent tremor, inducible clonus

- Moderate- temperature up to 40°C, hypertension, hyperactive bowel sounds, spontaneous clonus, hyperreflexia, horizontal ocular clonus, agitation

- Severe- >41.1°C, rigidity usually replaces clonus, hypertonicity, seizures, renal failure, DIC

- Hyperthermia, seizures and elevated CK activities indicate severe serotonin syndrome and may portend a poor prognosis without treatment [9]

- Rapid onset within 24hrs of dose increase or second agent added will help distinguish from other toxidromes such as NMS [2]

- Resolution within 24hrs of discontinuation of offending agent(s)

Evaluation:

- ABCs and Vital signs

- Assess for airway compromise as severe chest wall rigidity may require immediate paralysis and intubation

- Hypertension is common, however, hypotension can be seen in MAOI use

- When possible, review patient’s history of prescription medications, OTC medications, herbal supplements and illicit substances [5]

- Perform a focused physical exam

- Tox exam: Vital Signs, Eyes, Mucous Membranes, Breath Sounds, Bowel Sounds, Skin Assessment, Reflexes/Neuro, and EKG.

- Hunter’s criteria can be used to determine whether a patient who has taken an overdose has significant serotonin toxicity. [11]

- 84% sensitivity, 97% specificity [3]

- Centered around the presence of clonus

- Several findings can distinguish SS from other syndromes [2]:

- Neuro: mydriasis, ocular clonus, hyperreflexia (more prominent in lower extremities), inducible or spontaneous clonus

- Abdomen: hyperactive bowel sounds

- MSK: muscle rigidity with hyperkinesia

- Laboratory evaluation is not diagnostic but may aid in excluding other etiologies[5]

- Nonspecific findings include leukocytosis, acidosis, elevated creatinine, elevated creatine kinase, elevated transaminases [10]

- Diagnosis should be based on clinical evaluation[2]

Treatment:

- Discontinue the offending agent(s)

- Fluoxetine has a longer half-life (1-2wks) and may precipitate symptoms even after discontinuation [7]

- Goal of therapy is symptom relief with supportive care

- Hyperthermia will cause death

- Aggressive cooling measures and fluid resuscitation [7]

- Cooling measures as follows:

- Fans, water sprays, ice packs, cooled crystalloids, cooling blankets [1]

- Severe cases: muscle paralysis, endotracheal intubation, and ventilation [1]

- No role for antipyretics as hyperthermia is caused by increased muscle activity

- Agitation will worsen hyperthermia

- Benzodiazepines are first line and lower risk of lactic acidosis and rhabdomyolysis [5]

- Vecuronium is preferred for paralysis because succinylcholine has theoretical risk of hyperkalemia and could potentially worsen ongoing rhabdomyolysis

- Hypertension or hypotension

- Short acting anti-hypertensives such as Esmolol or Nitroprusside if benzodiazepines are not sufficient to lower blood pressure [1]

- Hypotension can be a problem in those taking MAOI, and preferred treatment includes low doses of direct acting sympathomimetics (norepinephrine, epinephrine, or phenylephrine)[1]

- Hyperthermia will cause death

- Special considerations

- Cyproheptadine is a 5-HT2A and H-1 receptor antagonist, classically referred to as an “antidote”

- No randomized control studies to support its effectiveness [8] but has been used in severe, refractory cases

- Only available in PO form, absorption can take hours

- Initial dose 12mg, then 2mg every 2hrs as needed, max 20mg daily

- Haloperidol has demonstrated effectiveness in animal studies [7]

- Avoid Bromocriptine as it has serotonergic effects and can worsen symptoms

- Dantrolene, while used for malignant hyperthermia, has not been shown to be helpful in serotonin syndrome [12]

- Cyproheptadine is a 5-HT2A and H-1 receptor antagonist, classically referred to as an “antidote”

Disposition:

- Most mild cases do not need hospital admission [13] but may be observed for at least 6 hours [12]

- Moderate cases warrant admission for cardiac monitoring and further observation

- Severe, life-threatening cases should be admitted to the ICU as sedation, paralysis and intubation are necessary

Pearls:

- Consider with history of polypharmacy, antidepressant, or opioid use

- Presentation has fast onset and resolution

- Clonus is a key physical exam finding

- Hyperthermia, seizures, and rhabdomyolysis indicate severe serotonin syndrome

- Treatment is supportive, targeting hyperthermia and agitation

A 21-year-old woman with a history of depression and anxiety presents to the ED with fever and diaphoresis. She denies cough, dysuria, abdominal pain, rash, or recent travel. She is compliant with her medications and began taking a new one today. She appears restless and agitated. Her vital signs are T 102.0°F, HR 124 beats/minute, RR 16 breaths/minute, BP 150/95 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Her blood glucose is 112 mg/dL, and her urine pregnancy test is negative. Which of the following findings suggest the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome?

A) Bilateral miosis

B) Cogwheel rigidity

C) Lower extremity clonus

D) Torsional nystagmus

Answer: C

Serotonin syndrome is a clinical constellation of findings that result from excessive serotonin neurotransmission. It is caused by either serotonergic medications or a combination of medications that result in a hyper-serotonergic state within the central nervous system (CNS). The most common drug class responsible for serotonin syndrome is antidepressants. The onset is typically between two and 24 hours after a serotonergic medication dose has been increased or a second serotonergic agent has been added. The clinical syndrome is manifested by cognitive or behavioral, neuromuscular, and autonomic findings. These can include agitation, altered mentation, diaphoresis, hyperthermia, tachycardia, mydriasis (not miosis), muscle rigidity, hyperreflexia, lower extremity clonus, restlessness or akathisia, and tremor. Of these altered mental status, increased muscle tone, and hyperthermia are the most commonly reported among patients with serotonin syndrome. Because many of these symptoms, even in combination, are nonspecific, the diagnosis is frequently missed. Providers should keep a high index of suspicion and complete a thorough history including medication use and social history. The finding of myoclonus is important because other clinical syndromes that mimic serotonin syndrome do not exhibit myoclonus. Because there is no laboratory test to confirm the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome, the diagnosis is essentially clinical based on history and physical examination findings. Treatment is mainly supportive and involves discontinuing all serotonergic agents. Endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation, external cooling, benzodiazepines for agitation, and intravenous antihypertensives for hypertension may be needed. Cyproheptadine can be considered for refractory cases. Patients should be admitted until symptoms have resolved.

Bilateral miosis (A) would not be expected, but rather mydriasis, in serotonin syndrome. Cogwheel rigidity (B) is more common in neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a condition that is commonly mistaken with serotonin syndrome. Torsional nystagmus (D) suggests a CNS pathology such as acute cerebellar stroke or vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency, or may be seen in dextromethorphan overdose. Nystagmus is not a classic finding of serotonin syndrome.

Further Reading:

FOAMed:

emDocs – Serotonin Syndrome vs. NMS

References:

- Scotton WJ, Hill LJ. Serotonin Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, Management, and Potential Future Directions. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2019; 12:1-14. DOI: 10.1177/1178646919873925.

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The Serotonin Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 17; 352:1112-20. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra041867.

- Dunkley EJC, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. 2003; 96:635-642. DOI:10.1093/qjmed/hcg109.

- Millas DG, Lovell EO. Antibiotic-Induced Serotonin Syndrome. J of Emerg Med. 2011; 40(1):35-27.

- Nordstrom K, Vilke GM, Wilson MP. Psychiatric Emergencies for Clinicians: Emergency Department Management of Serotonin Syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2016; 50(1):89-91.

- LoVecchio F, Mattison EG. Atypical and Serotonergic Antidepressants. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill; 2020.

- Martin TG. Serotonin Syndrome. Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Mar 27; 28:520-526.

- Tormoehlen LM, Rusyniak DE. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome. In: Romanovsky, AA. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol 157 3rd Series. Elsevier; 2018.

- Prakash S, Rathore C, Rana K, Prakash A. Fatal serotonin syndrome: a systematic review of 56 cases in the literature. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021 Feb;59(2):89-100. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2020.1839662. Epub 2020 Nov 16.

- Nguyen H, Pan A, Smollin C, Cantrell LF, Kearney T. An 11-year retrospective review of cyproheptadine use in serotonin syndrome cases reported to the California Poison Control System. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44:327-334.

- Isbister GK, Buckley NA, Whyte IM. Serotonin toxicity: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Med J Aust. 2007 Sep 17;187(6):361-5.

- Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Serotonin Syndrome. Oschner J. 2013;13(4): 533-540.

- Ables AZ, Nagubilli R. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Serotonin Syndrome. Am Fam Physician.2010;81(9):1139-1142.

One thought on “EM@3AM: Serotonin Syndrome”