Author: Lloyd Tannenbaum, MD (EM Attending Physician, APD) // Reviewer: Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Hello and welcome back to ECG Pointers, a series designed to make you more confident in your ECG interpretations.

Disclaimer: This is a fictional case and morbidity and mortality conference. This case did not happen.

ER Chairman, Dr. Sullivan: “Good morning. For this month’s Morbidity and Mortality (M and M) Conference, we will be discussing a recent death in the emergency room. Joining us today, in addition to my ER colleagues, we have representatives from the departments of congenital cardiology, cardiac anesthesia, critical care, and pharmacy. Our case today involved patient, JM, who was a 32-year-old male coming into the ER complaining of shortness of breath. Dr. Jackson, he was your patient, please present this case to the room. As with all M and M conferences, please remember that everything discussed is confidential and designed for honest reflection and growth, not blame. For those of us in attendance today who are not part of the ER, please feel free to interrupt Dr. Jackson as he presents to ask any clarifying questions as needed. Go ahead Dr. Jackson.”

Dr. J: “Thank you Dr. Sullivan. And thank you to my colleagues both from the ER and from other departments who have taken time out of their busy day to discuss our care. This was a tough case; one that I think will really benefit all of our departments from reviewing. Patient JM presented to the ER during a busy Friday night shift by car. It was around 8 pm when he checked in. He was initially triaged as a level 1 patient, meaning that he needed to get brought back from the waiting room, ideally as soon as possible. Looking over the nurse’s triage notes, she wrote that the patient was complaining of shortness of breath for the past 3-4 days, but it was getting progressively worse, to the point that he could no longer speak in full sentences. Nursing notes mention that they called for a stat bed, but unfortunately, none were available. One was being cleaned, however, and it was reserved for JM. Triage vitals show an O2 sat of 78% on room air, heart rate of 126, respiratory rate of 27, blood pressure of 140/83, and a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius (98.6F). Once vitals were obtained, nursing again called for a stat bed, placed the patient on oxygen (6L NC), and alerted respiratory therapy to be on standby. The patient remained in the triage room for an additional 5-7 minutes until the room was available, during which time an ECG was performed. After completing the ECG, the patient was wheeled immediately to the room and nursing asked me to come over and look at him right away.”

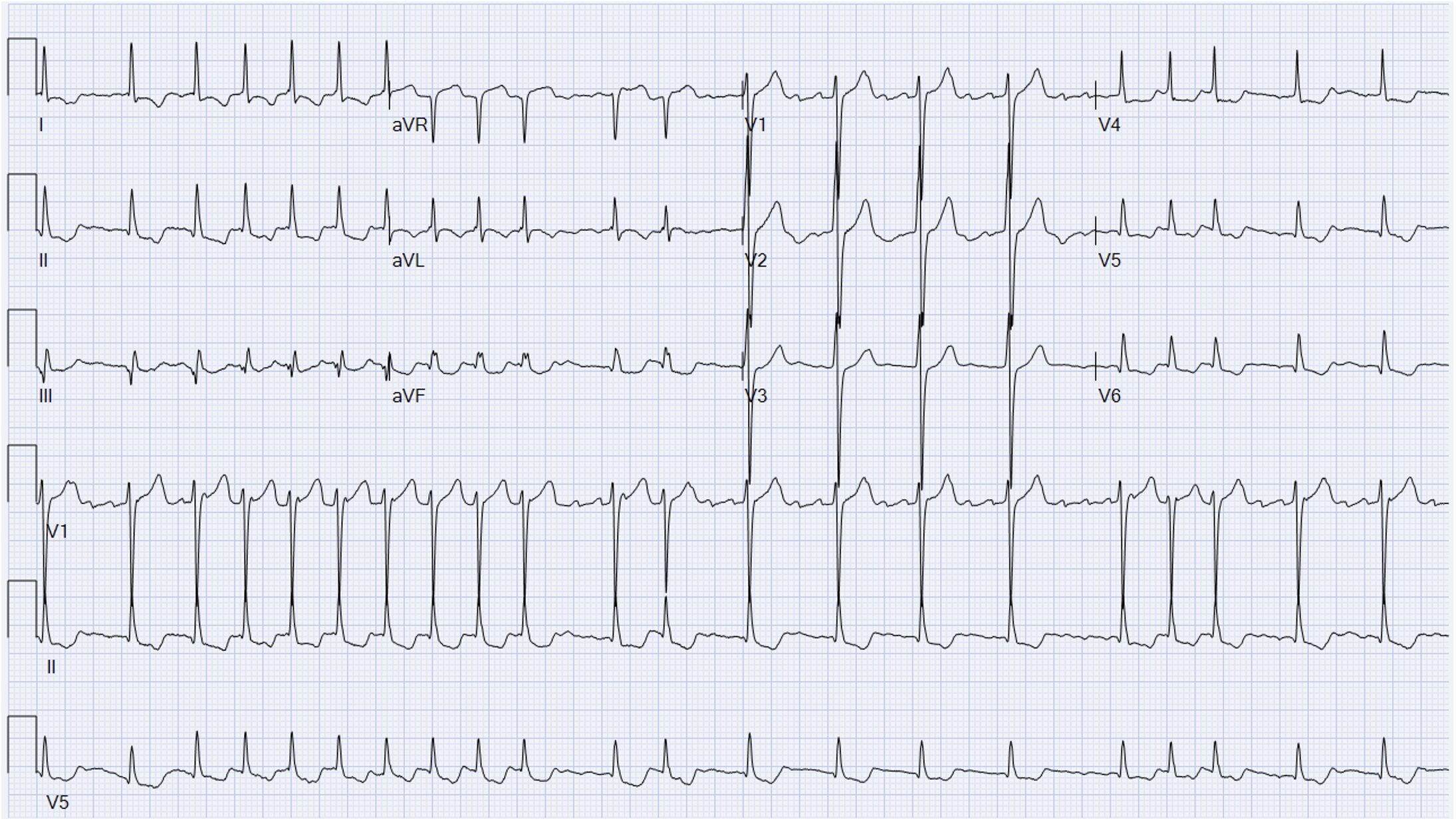

Dr. J: “I met the patient at the room and saw an early 30s-year-old male in distress. He was short of breath. He had audible rales and rhonchi from across the room and looked unwell. I called RT to the bedside and asked them to get BPAP ready, as the patient appeared to be in some kind of heart failure exacerbation or volume overload state. When I tried to get more history from him, he kept saying, ‘I can’t breathe! I … Can’t … Breathe!’ He was able to tell me that his mother was on her way, and he kept pointing to his chest and said ‘Tan! Tan!’ but we weren’t sure what that meant. At this time, the tech handed me his ECG, which I have enlarged and displayed on the screen. If you’d all please take a second to review his ECG:”

Dr. J: “I interpreted the ECG as:

Rate: 126 bpm

Rhythm: irregularly irregular, but with P waves; very confusing

Axis: Normal

Intervals: Narrow QRS, variable PR, sometimes PR not present

Morphology: Some ST segment depressions, some ST elevation in AVR, likely some strain going on

Final read: I read this ECG to show some kind of atypical atrial rhythm with signs of strain. Given the P wave’s axis, they aren’t coming from the SA node. I was concerned for possible multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT), but all of the P waves looked the same, making MAT less likely.”

Dr. J: “At this time, the nurse had pulled up JM’s chart, and as I finished looking at the ECG, I heard her say, ‘He has a Fontan and a history of hypoplastic left heart syndrome.’”

Dr. Kimber: “Pardon me, may I interrupt for a second? I’m Dr. Kimber from the department of congenital cardiology. I’d like to just spend a few seconds going over this ECG; I think there are a lot of good learning points to take away from it. You are correct; this is an atypical atrial rhythm, likely atypical flutter. Fontan patients are at high risk for atrial dysrhythmias, stemming from years of stretch being placed on their atria, given their abnormal cardiac mechanics. Typical flutter usually presents as a circuit around the tricuspid valve and tends to have a predictable rate. For atypical flutter, as often seen in these patients, it can be irregular since the circuit isn’t around the tricuspid. Remember, Fontan patients are very sensitive to atrial dysrhythmias, Dr. Jackson, what happened next?”

Dr. J: “Thank you Dr. Kimber. At this point, I think we all knew JM was in trouble. Once we recognized that he was a Fontan patient, we took the BPAP mask off of him immediately and I asked the charge nurse to stat page the congenital team. I think the BPAP was only on him for 30-60 seconds. RT had just finished setting it up when I ripped it off of him. I know how sensitive Fontan patients are to positive pressure ventilation. We placed a non-rebreather (NRB) mask on JM and cranked it up to 15L. Also, we tried to get more history out of JM, but he was so short of breath, he could barely talk. We did finally figure out that “Tan” and pointing to his chest meant that he is a Fontan patient, but unfortunately, Mom still had not arrived. Right around now, stat labs were being run, and I took a look with the ultrasound. I’ve blown up some images on the screen ahead to review:”

Dr. J: “I was really worried about his volume status. I took a look at his IVC to see if it was plethoric or not. Here is a clip I recorded, showing a severely dilated IVC.”

Dr. Kimber: “This was a good thought, but these patients will always have a dilated IVC. Think of them as living in chronic right heart failure; they will always have a dilated IVC. Unfortunately, you can’t trust an IVC POCUS to help you with volume status in these patients.”

Dr. J: “That’s unfortunate. Thanks Dr. Kimber. Then I took a look at his heart and recorded the following two images:

Dr. J: “To be honest, as an ER doc, this is beyond my US abilities. Dr. Kimber, would you be able to go over what we were seeing on US?

Dr. Kimber: “Of course: (Take a look at the video below)”

Dr. J: “This is when it started to get really bad. Despite 15L NRB, JM was still not doing well. His chest x-ray showed severe volume overload, and we were struggling with ways to get the fluid off of him. His initial venous blood gas showed a pH of 6.89 with a CO2 over 140, O2 of 20, and a bicarb of 21. I interpreted this as a severe respiratory acidosis. Vital signs showed a heart rate in the 140s now, still irregular, blood pressure of 100/65, SpO2 around 75-80% on the NRB at 15, and respiratory rate closer to 30-35 now. While I recognize now that it was not ideal, we made the decision to intubate JM. As we were getting set up for intubation, his mom arrived and was brought right back to the bedside. I introduced myself, explained that her son was critically ill, and discussed the need for emergent intubation. She was extremely worried and talked about how every other time he’s needed to be intubated it involved a special congenital cardiac team. I explained to her that I did not have time to request back up and that I was worried her son was about to code.”

Dr. J: “At this point, Dr. Kimber and the congenital team called me back. Dr. Kimber, would you like to take it from here?”

Dr. Kimber: “Sure, thank you. As you said, Dr. Jackson, JM was critically ill. You and I spoke briefly and reviewed his clinical status, the VBG that was back, his chest xray, and his ECG. I agreed with you that this was likely an atypical flutter and needed immediate attention. I recognize that the patient may need intubation, but I asked you to first anticoagulate him and then perform a synchronized cardioversion to get him back into sinus rhythm. Fontan physiology is HIGHLY dependent on low atrial pressure and effective atrial contraction in order to maintain cardiac output. When these patients have abnormal atrial dysrhythmias (which they are at high risk for, given their altered anatomy), they are at high risk for hemodynamic compromise, heart failure, thromboembolic events, and have an increased risk of mortality.

Dr. J: “Correct, with your assistance, we made the decision to start the patient on heparin, push a small amount of fentanyl quickly for pain control, and emergently cardiovert JM out of his atrial dysrhythmia. The cardioversion was successful; he was back in normal sinus rhythm, but he still could not breathe. Honestly, at this point, it seemed like he was getting worse; I think he was beginning to tire out from breathing so hard. Given his clinical picture, I asked pharmacy for any medication recommendations for a crash intubation on a Fontan patient. Scott, do you want to chime in now?”

Scott: “Sure, hi everyone, Scott from the department of pharmacy. What a tough case. From everything I know about intubating a Fontan patient, the rule of thumb is, ‘Don’t intubate a Fontan patient, especially not in the ER.’ But sometimes you have to break rules. From a pharmacy point of view, I recommended etomidate for induction and rocuronium for paralysis. Goals here are not to drop preload and not to depress ventricular function. Etomidate should give the least hit to systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and contractility of the induction agents, and rocuronium will hopefully avoid the sympathetic swing that you can see with succinylcholine. I recommended against propofol as it can cause a rapid drop in preload and SVR.”

Dr. J: “Thanks Scott. Next, I called the OR to see if they happened to have anyone in house for cardiac anesthesia who may be able to offer some tips for intubating a Fontan patient. While he wasn’t in house, luckily Dr. Philippo was willing to call and go over some ideas he had about intubation. Dr. Philippo, would you like to go over your recs?

Dr. Philippo: “Sure, no problem. Hello everyone, Dr. Philippo, director of cardiothoracic anesthesia. I do a significant amount of work with complex cardiac cases. Intubating a Fontan patient is extremely challenging. These patients are extremely tenuous and very sensitive to small changes that can cause huge problems. For these patients, I recommend at least 2 large bore peripheral IVs AND an arterial line. If you’re relying on a peripheral blood pressure cuff alone, by the time you find out that the patient is hypotensive, it will be too late. I’d consider a central line too, but with the way he’s breathing and his volume status, I doubt the patient will be able to lay flat to tolerate it. I also have an epi drip primed and already connected to one of the IVs, as I can almost guarantee that the patient will be hypotensive at some point during the intubation process and require emergent pressors. This needs to be a slow, controlled intubation with everything as optimized as possible. Even if you prep to do everything right, Fontan patients can still crash during induction. Once the tube is in, you need to use the lowest PEEP possible.”

Dr. J: “And what about meds for induction Dr. Philippo?”

Dr. Philippo: “Fontan patients do not do well with positive pressure ventilation. For this patient, I agree with Scott on using etomidate, but I would recommend succinylcholine for paralysis. It will work quicker and time is of the essence here. Additionally, the succinylcholine will wear off quickly and I’ll have the option to let the patient spontaneously ventilate, which I probably won’t do but at least the option is there.”

Scott: “Dr. Philippo, with the succinylcholine, I’d be worried about a sympathetic swing, given how worked up the patient is. The last thing we want is for him to lose his sympathetic drive. Would you premedicate the patient before induction?”

Dr. Philippo: “Exactly. I’d probably give him a fentanyl bolus to really blunt that response. Like we’re both saying, these patients are extremely tenuous. It’s highly likely he arrests during induction.”

Dr. Kimber: “I’d actually recommend no paralytic for this patient. I’d probably reach for ketamine or etomidate, but avoid paralysis, if possible.”

Scott: “I’d still lean towards rocuronium…”

Dr. Sullivan: “Gentlemen, thank you for highlighting a common problem in the ER. We have very little time to make a quick decision on an unstable patient with many specialized consultants having differing opinions, all of which are likely not wrong, but maybe not best either. Dr. Jackson, what did you decide to do?”

Dr. J: “Taking into account Dr. Kimber, Dr. Philippo, and Scott’s advice, I immediately placed an arterial line and ensured proper peripheral access. I think that was the fastest art line I’ve ever placed in my career. I knew we didn’t have a lot of time, and JM was really not doing well. We had an epi drip primed and connected. We had JM as optimally positioned as we could; we were as ready as we could be. I wanted the least amount of time between pushing meds and getting the tube in, so I decided to use a paralytic. Additionally, I was most worried about a sympathetic swing causing JM to crash, so I decided to go with roc and etomidate. Scott drew up the meds, and the whole team hoped for the best.”

Dr. J: “Despite all of our preparation and multiple specialists weighing in, as soon as we pushed induction and paralytic medications, JM immediately began to brady down, and his blood pressure on the art line dropped precariously. We started the epi drip at the max rate and gave a bolus of push dose pressors, but unfortunately, it didn’t have much of an effect. The art line went flat. I know in the ER we don’t call a “Code Blue” but we initiated ACLS immediately and started CPR. I was able to secure the airway quickly. I also placed a call to critical care for emergent ECMO, but the ECMO team was unavailable. We coded JM for 45-60 minutes, but unfortunately, never were able to get ROSC. It’s never easy to have a patient come in talking and end up in the morgue. My team and I took this patient’s death pretty hard.”

Dr. Inman: Dr. Jackson, what a tough case. I apologize that the ECMO team was unavailable to assist; we were actively cannulating a different patient in the hospital when you called. When you placed the arterial line, what vessel did you use?”

Dr. J: “I used the right radial artery, why?”

Dr. Inman: “Just something to think about next time; consider using the common femorals in a crashing patient for both an arterial line and a central line. These can help us save time when we canulate for ECMO if you’ve already accessed these vessels.”

Dr. J: “Thank you.”

Dr. Sullivan: “Thank you everyone, excellent discussion on a very sad outcome. Scott, Drs. Kimber, Philippo, and Inman, thank you for your expertise. Dr. Jackson, we will continue to review this case and let you know if the department has any follow up questions. That will conclude today’s M and M. Thank you.”

Case Wrap up:

- These patients are incredibly complex, they shouldn’t be managed alone.

- Most patients or their families have a way to get in touch with their cardiologist emergently; don’t be afraid to ask them.

- Intubating a fontan patent is incredibly complex and very dangerous.

- Rule number one is don’t intubate these patients

- They are incredibly sensitive to induction and will likely crash during induction

- Fontan patients are incredibly sensitive to positive pressure ventilation.

- Even high flow nasal cannula can be too much for them.

- These patients live in a state of chronic RV failure, so an IVC ultrasound will not help you assess volume status

- If you need central access or an arterial line in a crashing patient who may need ECMO, consider using the common femorals, as they can give the ECMO team a head start when they come to cannulate.

- A BIG thank you to Scott and Drs. Kimber, Philippo, and Inman for their expertise and management suggestions.