Author: Lloyd Tannenbaum, MD (EM Attending Physician, APD, Geisinger Wyoming Valley, PA) // Reviewer: Anthony Spadaro, MD (Fellow in Medical Toxicology, Rutgers NJMS) and (Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Hello and welcome back to ECG Pointers, a series designed to make you more confident in your ECG interpretations. This week, we feature a post from Dr. Tannenbaum’s ECG Teaching Cases, a free ECG resource. Please check it out. Without further ado, let’s look at some ECGs!

“Hey, we need some help with this admitted patient NOW!” you hear one of your nurses tell you.

You hustle over to her room and see a 23-year-old male in extremis. He is shaking, he’s dripping sweat, and looks very unwell. He tells you that everything hurts and he feels like he can’t breathe.

Your charge nurse, Shannon, comes over and catches you up. “This is Mr. Jones. He came in from the local substance use rehab facility. He has a history of fentanyl abuse and last used 6 hours ago. He states that his dealer gets his stash from Philadelphia. This is his second episode of this ‘shaking/sweating/can’t breathe’ thing. The first one happened when he was en-route to us. EMS gave him some diazepam and it seemed to relax those symptoms. The admitting team isn’t quite sure what’s going on with him. Since you’re going to ask, here is his ECG:”

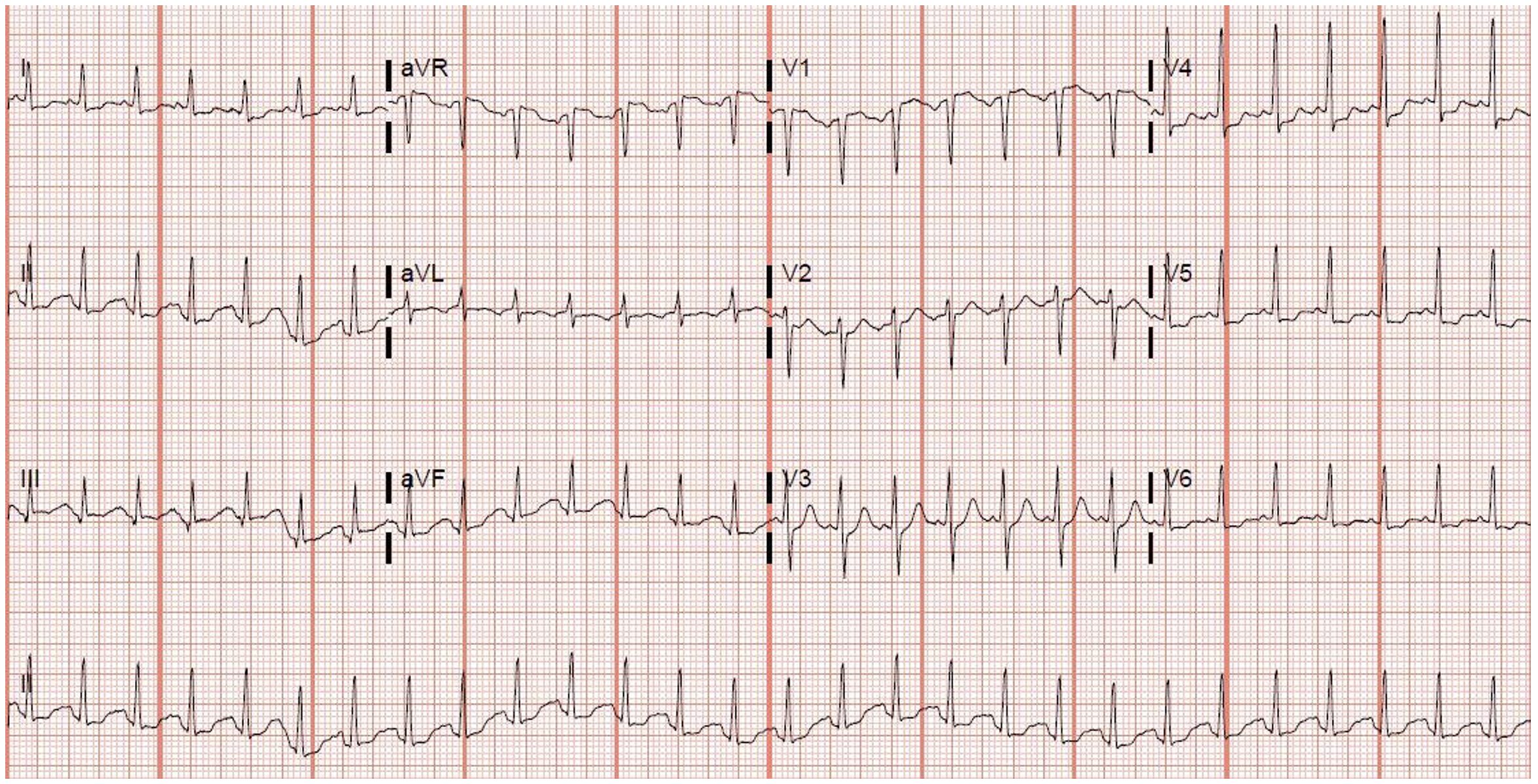

Rate: 160s

Rhythm: It’s challenging to see P waves in this ECG, but look closely at lead V2 and V3 and you can tease them out. This is sinus tachycardia

Axis: Normal

Intervals: Narrow QRS, normal PR, QTc looks ok too

Morphology: There is some evidence of strain given the ST segment depression in V4/V5/V6 and the ST segment elevation in aVR

Final Read: This is Sinus Tachycardia with strain. This heart is beating too fast!

“Doc, take a look at the rest of his vitals!” You hear Shannon tell you as she notices you staring at the ECG too long (again).”

He’s tachycardic as high as the 190s, his blood pressure is 201/142 mmHg, O2 sat is 96% on 2L NC. He’s afebrile and blood sugar was 140 when checked upon arrival.

This is not good. His twitching/shaking is getting worse. It looks like he’s having rigid myoclonic jerks that could be confused as a seizure, but he’s talking to you the entire time (so definitely not a seizure). He’s extremely anxious, diaphoretic, and vomiting. Something bad is going on, but what could it be?

[Please note, much of the following information comes from a Philadelphia Department of Public Health alert that can be found here (https://www.pa.gov/content/dam/copapwp-pagov/en/health/documents/topics/documents/2025%20HAN/2025-794-06-18%20Medetomidine%20Guidance.pdf) and a report from the CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/74/wr/pdfs/mm7415a2-H.pdf). Much of this information is expert consensus and, more evidence will emerge that may change these recommendations because this is so new; this is also much more toxicology than my typical emergency cardiology case, but those of us in the northeastern region of the USA will definitely be seeing it soon, and it may be spreading to an ER near you, so please be on the lookout!]

It’s not uncommon for street drugs (such as fentanyl) to be cut (or mixed) with different substances. In the past several years, we’ve seen an increase in opioids being cut with xylazine (street name Tranq). Xylazine is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist and is traditionally used as a veterinary anesthetic. We’ve seen fentanyl and Xylazine being mixed on the streets for the past few years (also called Tranq Dope) but, medetomidine is something new.

Medetomidine is a synthetic alpha-2 agonists sedative that is 100-200 x more potent than xylazine. Medetomidine is the racemic mixture of levo-medetomidine and dex-medetomidine (commonly used in the hospital as Precedex). From September 2024 to January 2025, 165 patients were hospitalized at different hospitals in Philadelphia for abnormal opioid withdrawal. Not only did these patients have the traditional symptoms (nausea, vomiting, sweating, agitation, etc.), they also had autonomic dysfunction, such as severe hypertension and tachycardia. Importantly, these patient’s symptoms that did not resolve with medications that are classically used to treat fentanyl and xylazine withdrawal. Testing showed that much (>70%) of the fentanyl supply in Philadelphia, PA is being mixed with medetomidine, largely replacing xylazine in the drug supply..

So what symptoms are we seeing and what is the timeline?

Medetomidine withdrawal starts abruptly within hours of last use and progresses rapidly. It has been reported to occur 18-36 hours after the last drug use, however the timeline of medetomidine is not well described other than patients can appear okay before decompensating rapidly.

Symptoms include:

- Tachycardia

- Severe Hypertension

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Waxing and waning alertness

- Anxiety

- Severe diaphoresis

- Restlessness

- Tremor/Myoclonic jerks

How do we treat these patients?

- Consider IV/IM route for medications since patients often have significant vomiting.

- Initiate alpha-2 agonists, such as dexmedetomidine or clonidine, EARLY (PA Dept of heath recommends Clonidine).

- Treat the opioid withdrawal symptoms with buprenorphine, methadone, or a short-acting fullopioid agonist such as morphine.

- These patients will need intensive monitoring (vital sign checks every hour, if not connected to continuous monitoring).

- Check an ECG (the best part) and monitor for signs of demand ischemia. QTc prolongation may occur in the setting of electrolyte derangements from vomiting, critical illness, and concurrent medication use.

- Treat anxiety and nausea/vomiting with medications such as olanzapine, haloperidol, ondansetron, benzodiazepines. (PA Dept of heath recommends olanzapine).

- Treat any concurrent pain, consider a ketamine infusion, short-acting opioids, or NSAIDS.

- SOME OF THESE PATIENTS will require a dexmedetomidine infusion in the ICU.

- ***WATCH OUT for concomitant medical problems such as heart disease, COPD/Asthma, liver, psych disorders that can be exacerbated by the severe autonomic dysregulation***.

***Please be aware, if you are a first responder responding to an overdose patient, when you give naloxone, check for BREATHING first, instead of responsiveness, as the patient may still be sedated from the medetomidine. The goal of giving naloxone in overdose is to restore an adequate respiratory rate from the opioid induced respiratory depression, not return the patient to a normal mental status. ***

Why Dexmedetomidine?

Great question. Dexmedetomidine (aka Precedex) is related to medetomidine. Dexmedetomidine is one half of the racemic mixture that makes up medetomidine. Prolonged exposure to dexmedetomidine can produce similar withdrawal symptoms as medetomidine and is traditionally reversed by a slow, controlled weaning off of the drug. From the CDC’s recent brief on the initial 165 patients in Philadelphia, 137 (83%) were treated with and responded to Dexmedetomidine. Please be aware, of the 165 patients, 91% required ICU admission and 24% required intubation. Please be careful with these patients. Some come in looking like a traditional fentanyl overdose, get admitted to the floor, and then crash. Involve your toxicology colleagues and addiction medicine colleagues early.

Case wrap up:

“SCOTT! I need some help in here. I need some clonidine and Olanzapine, now!”

“I’ll let the ICU team know then need to come down and upgrade this patient from floor holding to ICU holding,” Shannon tells you. You, Scott, and the nursing team scramble to stabilize Mr. Jones’s blood pressure and heart rate. The ICU team comes down and takes over care.

Case Review:

- Please be aware that there is a new drug (medetomidine) present in the street fentanyl supply, causing severe and life-threatening withdrawal symptoms

- The Pennsylvania Department of Health and the CDC have put out several articles reviewing signs and symptoms of medetomidine withdrawal, which are linked below

- Symptoms include traditional opioid withdrawal and AUTONOMIC INSTABILITY

- Watch out for severe hypertension and tachycardia

- Consider treating their symptoms with clonidine, olanzapine, and potentially a dexmedetomidine drip

- Many of these patients will require an ICU admission

- Involve your toxicology, regional poison center (1-800-222-1222), and/or addiction medicine specialists early

- Information on this complex overdose is constantly evolving.Here are 2 more articles that may help with management:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40310861/ – From the University of Pitt’s Tox group noting that median peak blood pressure was 200/114 and median peak heart rate was in the 160s. Interestingly 30% of patients had a myocardial injury, likely secondary to demand

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15563650.2025.2500601?scroll=top&needAccess=true#d1e274 – From Temple University’s Tox group. This study looked more at medetomidine overdose than withdrawal but noted that these patients had bradycardia in the 30s-40s with a (mostly) normal blood pressure.