Authors: Alessia Cooney, DO (EM Resident Physician, North Shore/LIJ, Manhasset, NY); Alexander Nello, DO (EM Attending Physician, North Shore/LIJ, Manhasset, NY) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 72-year-old male with a past medical history of BPH and HTN presents from a subacute rehab facility for altered mental status. Per staff, the patient has had two days of confusion, subjective fevers, and foul-smelling urine. He has had a Foley catheter in place for the past 10 days following hospitalization for hip fracture repair. The patient’s daughter reports decreased oral intake and lethargy. He denies flank pain or hematuria.

Vital signs include BP 92/68, HR 110, T 103F rectally, RR 17, SpO2 98% on RA. Foley catheter is in place with cloudy urine in the Foley bag. His abdomen is soft and nontender, with no CVA tenderness bilaterally. While the patient appears tired, the rest of the exam is normal.

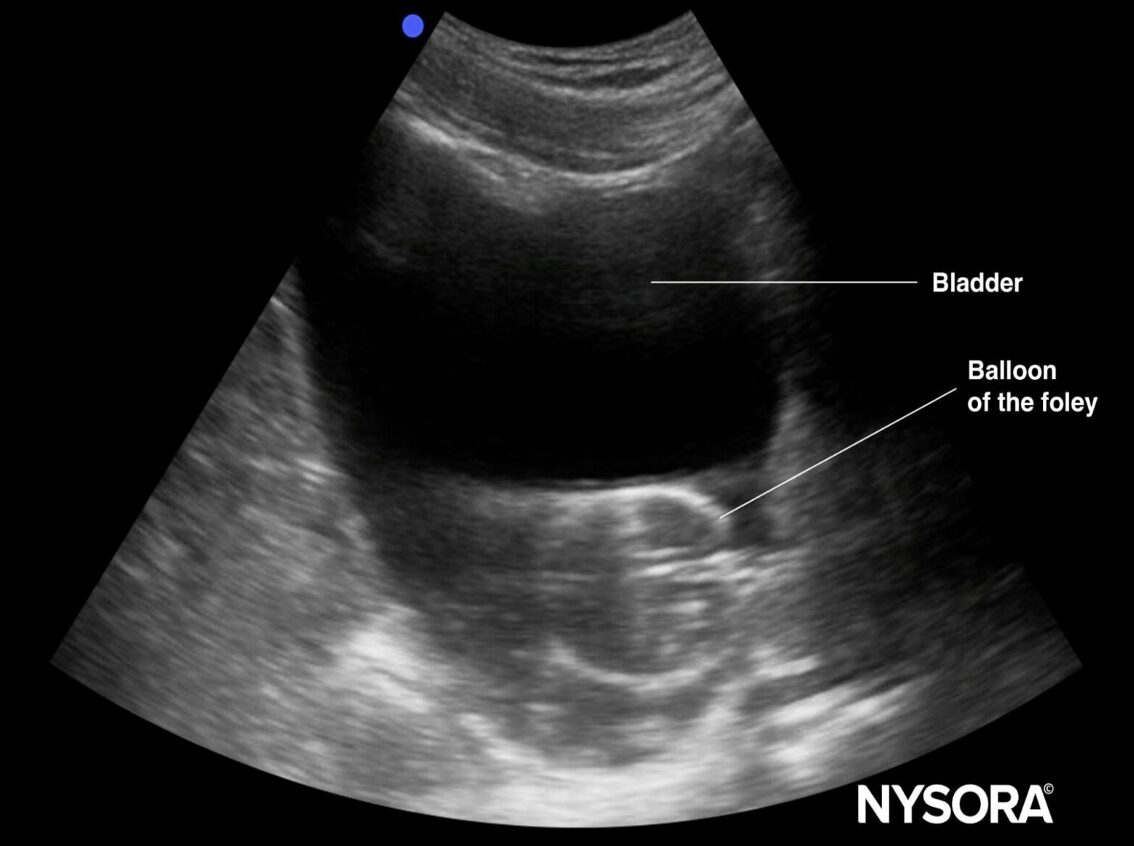

Ultrasound demonstrated a non-distended bladder with Foley balloon in good position.

UA from old Foley: >10 WBC per HPF

UA + Culture from new Foley: >10 WBC per HPF

Additional infectious workup negative including no leukocytosis.

Question: What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer: CAUTI (catheter-associated urinary tract infection)

Definition

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections, CAUTIs, are urinary tract infections that occur in patients whose bladder is catheterized or has been catheterized within the past 48 hours.1

- This includes patients who self-catheterize as well as those with suprapubic catheters.2,3

- Self-catheterized patients are especially susceptible if there is any breach in sterile technique when performing the catheterization or those with repeated catheterizations. Populations who self-catheterize are at lower risk for CAUTIs given prolonged exposure and biofilm formation are minimized.3,4

Background

- In the U.S., indwelling urinary catheters are responsible for as many as 80% of complicated urinary tract infections.1

- CAUTIs represent the most frequent hospital-acquired infection, contributing to roughly one million cases each year.1

- CAUTIs are the leading cause of secondary bloodstream infections.1

- The length of time a catheter remains in place is the strongest predictor for developing bacteriuria, with an estimated daily risk between 3–7%.1

Pathophysiology

- Urinary Tract Infection: translocation of rectal flora → invasion mediated by pili and adhesions → neutrophils infiltrate and bacteria multiply which forms a biofilm.1

- Biofilms are made up of microbes and their metabolic products that adhere to one another and the surface of the catheter. This forms an extracellular polymeric matrix that inhibits diffusion of antibiotics and host responses which allows for infection to persist.1

- Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection1

- Catheters provide a direct channel for rectal and periurethral microbe ascension to the bladder.

- Biofilm formation is initiated within minutes of catheterization and progresses as the length of indwelling time increases.

- Placement of catheters can irritate and traumatize the uroepithelium, thereby disrupting the physiologic mucopolysaccharide coating which renders the tract more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

- Catheter insertion also causes an immune response which leads to fibrinogen accumulation on the catheter which produces an environment where pathogens can adhere through use of their fibrinogen-binding proteins.

- Over time, most patients with a urinary catheter will develop bacterial colonization of their bladders. This is also commonly seen in normal elderly people as well, even without having urinary catheters (asymptomatic bacteriuria).6

- Elderly people are more prone to persistent bladder bacterial colonization due to age-related immune decline, epithelial changes, and urinary tract abnormalities.5

Clinical Presentation

- Not every patient with an indwelling catheter has CAUTI.

- Signs and symptoms to look out for include:6,7

- New onset/worsening fever – without alternative explanation

- Rigors – without alternative explanation

- Altered mental status – without alternative explanation

- Flank pain

- Costovertebral angle tenderness

- Acute hematuria

- Pelvic discomfort

- Malaise or lethargy – without alternative explanation

- Worsening spasticity or autonomic dysreflexia in a patient with chronic spinal cord injury

- If patient had the catheter removed in the last 48 hours they may present with:7

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary urgency

- Suprapubic pain/tenderness

- Since having a catheter in place could cause complaints of “frequency,” “urgency,” or “dysuria” this would not be considered a sign of a CAUTI unless symptoms are present when catheter removed.8

- Cloudy or malodorous urine is not a valid indicator of a CAUTI.6, 9, 10

- One clinical trial demonstrates that smell fails at predicting pyuria with bacteriuria.9

Evaluation

- Foley function

- Check Foley flushes properly

- If patients are asymptomatic and just have a nonfunctional foley there is no indication to obtain routine urinalysis after foley catheter exchange regardless of duration of catheterization. All indwelling rapidly develop a biofilm and bacterial colonization so urinalysis would likely reflect colonization rather than acute infectiona.2

- Ultrasound:6,11

- Under distended bladder indicates that Foley is functioning properly.6,12

- Ultrasound:6,11

Image One: Ultrasound image of an under distended bladder with inflated Foley balloon in place.12

- Distended bladder indicates that the Foley is malfunctioning which puts patients at a higher risk for pyelonephritis, obstructive renal failure and septic shock.7,11

Image Two: Ultrasound image of a distended bladder with inflated Foley balloon surrounded by hypoechogenic fluid11

- Replace Foley and recheck urinalysis WITH culture

- Only proceed to obtain UA/culture if you have signs/symptoms compatible with CAUTI AND there is no other possible identified source for the presenting signs/symptoms.7

- Replace the Foley catheter before collecting urine studies to avoid contamination from biofilm and to enhance antibiotic effectiveness by removing a potential source of reinfection.6,13

- Replace Foley regardless of whether it is functional

- Confirm the original reason for Foley catheter placement to ensure that removal will not interfere with healing from any recent urologic procedure.

- Suprapubic catheters can be exchanged by emergency physicians under sterile technique 7-14 days after initial placement to allow for the tract to mature.14

- Indwelling urinary catheters have no universally defined minimum timeframe in which they should remain in place before being exchanged. Urologic referral is recommended for patients with suspected urethral injury or difficulty placement.15

- >10 WBC per HPF AND >100,000 CFU/ml of pathologic bacteria is likely indicative of CAUTI if also present with compatible signs/symptoms.6-8

- Confirm the original reason for Foley catheter placement to ensure that removal will not interfere with healing from any recent urologic procedure.

Management

- There is no indication to treat pyuria (>5 WBC/hpf) and/or bacteriuria in the absence of signs or symptoms of infection.20

- Antibiotics (for nonpregnant patients)

- Evaluate whether patient has a history of multidrug resistance (MDR) based on prior urine cultures.21

- If prior cultures are positive for MRSA or VRE, add vancomycin or daptomycin/linezolid respectively.

- Outpatient – no MDR risk21

- Levofloxacin 500 to 750 mg orally once daily for 5 to 7 days or

- Ciprofloxacin 500 to 750 mg orally twice daily for 5 to 7 days or

- Ciprofloxacin extended-release 1000 mg orally once daily for 5 to 7 days

- Outpatient – MDR risk21

- Ertapenem 1 g IV or IM once

- Followed by:

- Levofloxacin 500 to 750 mg orally daily for 5 to 7 days or

- Ciprofloxacin 500 to 750 mg orally twice daily for 5 to 7 days or

- Ciprofloxacin extended-release 1000 mg orally once daily for 5 to 7 days or

- Fluoroquinolones are associated with slightly lower risk of treatment failure, higher rates of clinical cure and lower rate of repeat positive urine cultures post treatment.22

- Adverse events include tendinopathy, neuropathy, aortopathy, arrhythmia, and blood glucose disturbances. Fluoroquinolones should be avoided in patients over 60 years old.23Other alternatives include:21

- Cefpodoxime 200 to 400 mg orally twice daily for 7 days or

- Cefixime 400 mg orally once daily for 7 days or

- Cefuroxime 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days or

- Cefadroxil 1 g orally twice daily for 7 days or

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate 875 mg orally 2 or 3 times daily for 7 days or

- TMP-SMX 1 double-strength tablet orally twice daily for 7 days

- Adverse events include tendinopathy, neuropathy, aortopathy, arrhythmia, and blood glucose disturbances. Fluoroquinolones should be avoided in patients over 60 years old.23Other alternatives include:21

- Inpatient – septic shock or acute urinary tract obstruction21

- Meropenem 1 to 2 g IV every 8 hours infused over 3 hours or

- Imipenem 500 mg IV every 6 hours or 1 g IV every 8 hours infused over 3 hours or

- PLUS

- Imipenem and meropenem are generally effective against most Enterococcus faecalis and many Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains, even those resistant to broad-spectrum penicillins and cephalosporins; however, these organisms are typically resistant to ertapenem. Notably, meropenem shows reduced activity against faecalis compared to imipenem.24

- Vancomycin 15 to 20 mg/kg IV every 8 to 12 hours with or without a loading dose

- Inpatient – no MDR risk21

- Ceftriaxone 1 to 2 g IV once daily

- Inpatient – MDR risk21

- Cefepime 1 g IV every 12 hours or 2 g IV every 8 to 12 hours or

- Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV every 6 hours or 4.5 g IV every 8 hours or

- Imipenem 500 mg IV every 6 hours infused over 3 hours or

- Meropenem 1 to 2 g IV every 8 hours infused over 3 hours

- Duration of antibiotics for 5 to 7 days is effective for treating CAUTI.6,22

- Evaluate whether patient has a history of multidrug resistance (MDR) based on prior urine cultures.21

Disposition

- If concern for sepsis, admit to the hospital; otherwise, patient can be discharged home with oral antibiotics.

Pearls

- CAUTI is a urinary tract infection that occurs in patients whose bladder is catheterized or has been catheterized within the past 48 hours.

- Must have fever, rigors, AMS, flank pain, hematuria, or pelvic discomfort AND >10 WBC per HPF + >100,000 CFU/ml of pathologic bacteria to be classified as a CAUTI. Cloudy/malodorous urine alone is not diagnostic.

- Always replace the Foley catheter before obtaining a urine culture. Confirm with urology before replacing any Foley catheter that was placed in the context of a recent urologic procedure.

- Do not treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.

- Treat confirmed CAUTI with targeted antibiotics for 5–7 days. Admit if sepsis is suspected.

An 84-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and recurrent multidrug-resistant urinary tract infections presents to the hospital with altered mental status. His vital signs are BP 89/55 mm Hg, HR 110 bpm, RR 20/min, and T 38°C. He was admitted to the hospital 3 weeks ago to receive intravenous antibiotics for pneumonia. Today, his physical exam is notable for suprapubic and costovertebral tenderness. You note a serum lactate of 3.2 mmol/L on his initial point-of-care lab tests. His urinalysis demonstrates pyuria, and a urine culture was sent to the microbiology lab. Intravenous vancomycin is ordered. What additional antibiotic is the best choice for this patient?

A) Cefepime

B) Ceftriaxone

C) Levofloxacin

D) Meropenem

E) Piperacillin-tazobactam

Answer: D

This patient is presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with sepsis. His vital signs, elevated lactate, and altered mental status are concerning for systemic infection with evidence of end-organ damage. His medical history is notable for recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs). Patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia are at increased risk for bladder outlet obstruction, which predisposes them to the development of UTIs and prostatitis. Acute UTIs commonly present with dysuria, urinary frequency, or suprapubic pain. If the infection has spread beyond the bladder, the patient may present with symptoms of pyelonephritis, such as flank pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting. An acute UTI is consideredcomplicated in the presence of fever, systemic signs of infection, flank pain, costovertebral tenderness, or symptoms of prostatitis in men. In addition to suprapubic pain and pyuria, this patient also has systemic signs of infection, fever, and costovertebral tenderness. Therefore, his presentation is most consistent with sepsis due to acute complicated UTI.

The most common bacteria associated with acute complicated UTI is Escherichia coli. However, it may also be caused by other pathogens, such as Klebsiella, Proteus, and Pseudomonas. Recent antibiotic use, recent hospitalizations, or travel to regions with high rates of drug-resistant organisms increases the likelihood of drug-resistant pathogens. In a patient with an acute complicated UTI, the presence of critical illness or a known urinary tract obstruction should prompt treatment with broad–spectrum gram–positive coverage, such as vancomycin, as well as a carbapenem for broad-spectrum gram–negative coverage and coverage for extended–spectrum beta–lactamase (ESBL). Because this patient has sepsis and known urinary tract obstruction due to his enlarged prostate, the most appropriate antibiotic for empiric coverage is vancomycin and meropenem. ESBL is an enzyme produced by some gram-negative bacteria that lends resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillins, cephalosporins, and aztreonam. ESBL-producing organisms are becoming more prevalent and are commonly the cause of complicated UTIs. Risk factors for ESBL infection include prior history of ESBL infection, hospitalizations, recent antibiotic use, residence in long–term health care facilities, and presence of indwelling catheters. Antibiotic selection for patients with these risk factors who present with systemic signs of infection should include ESBL coverage. Carbapenems such as meropenem or imipenem are first–line therapy for ESBL organisms.

Cefepime (A) is a fourth-generation cephalosporin. Efficacy data does not support its use for the treatment of infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms, even if cefepime susceptibility is demonstrated.

Ceftriaxone (B) is a third-generation cephalosporin that would be an appropriate choice for an acute complicated UTI if there was no suspicion for drug-resistant organisms. This patient has risk factors for drug resistance, so he requires broader antibiotic coverage.

In addition to carbapenems, fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin (C) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are options for the treatment of complicated UTIs caused by ESBL-producing organisms. However, carbapenems are the preferred empiric therapy for this patient, who is likely bacteremic.

Piperacillin-tazobactam (E) is not recommended for the treatment of infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms due to conflicting evidence regarding their efficacy compared to carbapenems.

References

- Werneburg GT. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections: Current challenges and future prospects. Research and Reports in Urology. 2022;Volume 14:109-133. doi:10.2147/rru.s273663

- Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;68(10). doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1121

- Tenke P, Köves B, Johansen TEB. An update on prevention and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2014;27(1):102-107. doi:10.1097/qco.0000000000000031

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. Guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2024 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clinical Infectious Diseases. Published online March 5, 2024. doi:10.1093/cid/ciae104

- Ligon MM, Joshi CS, Fashemi BE, Salazar AM, Mysorekar IU. Effects of aging on urinary tract epithelial homeostasis and immunity. Developmental Biology. 2023;493:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2022.11.003

- Farkas J. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI). EMCrit Project. December 2, 2024. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/cauti/#is_CAUTI_real?

- Guideline for the management of catheter-associated … Accessed August 11, 2025. https://www.denverhealth.org/-/media/files/patients-visitors/referral-guides/catheterassociated-urinary-tract-infection-cauti-nonpregnant-adults.pdf.

- Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated … Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf.

- Loeb minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in … Accessed September 1, 2025. https://health.mo.gov/professionals/antibiotic-stewardship/guides/example-minimum-criteria-for-initiation-of-antibiotics-reference-sheet.pdf.

- Jump RLP, Crnich CJ, Nace DA. Cloudy, foul-smelling urine not a criteria for diagnosis of urinary tract infection in older adults. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2016;17(8):754. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.04.009

- Nysora. Ultrasound for Foley catheter: Positioning & Obstruction identification. NYSORA. March 14, 2024. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.nysora.com/education-news/ultrasound-for-foley-catheter-positioning-obstruction-identification/.

- Dinh V. Bladder Ultrasound Made Easy: Step-by-step guide. POCUS 101. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://www.pocus101.com/bladder-ultrasound-made-easy-step-by-step-guide/.

- Trautner BW, Darouiche RO. Role of biofilm in catheter-associated urinary tract infection☆. American Journal of Infection Control. 2004;32(3):177-183. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2003.08.005

- Hobbs C, Howles S, Derry F, Reynard J. Suprapubic Catheterisation: A study of 1000 elective procedures. BJU International. 2022;129(6):760-767. doi:10.1111/bju.15727

- MI; CFCS. Policies for replacing long-term indwelling urinary catheters in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27457774.

- Yan ST, Sun LC, Jia HB, Gao W, Yang JP, Zhang GQ. PROCALCITONIN levels in bloodstream infections caused by different sources and species of bacteria. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;35(4):579-583. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.12.017

- Julián-Jiménez A, Gutiérrez-Martín P, Lizcano-Lizcano A, López-Guerrero MA, Barroso-Manso Á, Heredero-Gálvez E. Usefulness of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for predicting bacteremia in urinary tract infections in the emergency department. Actas Urol Esp. 2015;39(8):502-510. doi:10.1016/j.acuro.2015.03.003

- Levine AR, Tran M, Shepherd J, Naut E. Utility of initial procalcitonin values to predict urinary tract infection. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;36(11):1993-1997. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.03.001

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49(11). doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000005337

- Givler DN. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. StatPearls [Internet]. July 17, 2023. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441848/.

- UpToDate. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/catheter-associated-urinary-tract-infection-in-adults?search=cauti&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H9.

- Langford BJ, Daneman N, Diong C, et al. Antibiotic selection and duration for catheter-associated urinary tract infection in non-hospitalized older adults: A population-based Cohort Study. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology. 2023;3(1). doi:10.1017/ash.2023.176

- Baggio D, Ananda-Rajah MR. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics and adverse events. Australian prescriber. October 2021. Accessed September 7, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8542490/.

- Carbapenems – Infectious Diseases. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Accessed September 10, 2025. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/bacteria-and-antibacterial-medications/carbapenems