Author: Michael Sperandeo, MD (Assistant Professor, Dept of Emergency Medicine, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Associate Program Director EMSL Medical Simulation Fellowship, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell); Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT) // Reviewed by: Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A previously healthy 32-year-old male presents to the ED via EMS following a high-speed motor vehicle collision on the interstate. He was a restrained driver involved in a head on collision. He reports he was wearing his seatbelt but the lower part of his abdomen hit the steering wheel. EMS had to help him out of the vehicle. He reports significant pain in the perineum and groin. He denies head strike and loss of consciousness. He denies chest pain or trouble breathing. He has intact sensation and motor function. He has the urge to urinate but is unsure if he is able to.

Vital Signs on arrival to the ED: HR 110, RR 18, blood pressure of 120/80, temperature (oral) of 99.1F, with an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. On exam he is protecting his airway and has breath sounds bilaterally. He has +2 pulses in all extremities. He can move and feel all extremities. GCS is 15. On secondary survey, the patient has mild diffuse lower abdominal tenderness. His pelvis is stable. He has no spinal tenderness and has intact rectal tone. There is no testicular swelling or pain; however, you observe blood at the urethral meatus.

Question: What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Genitourinary Trauma

Introduction

- Genitourinary (GU) trauma is rarely life threatening.1 It has a low mortality but is associated with high morbidity (especially if missed).

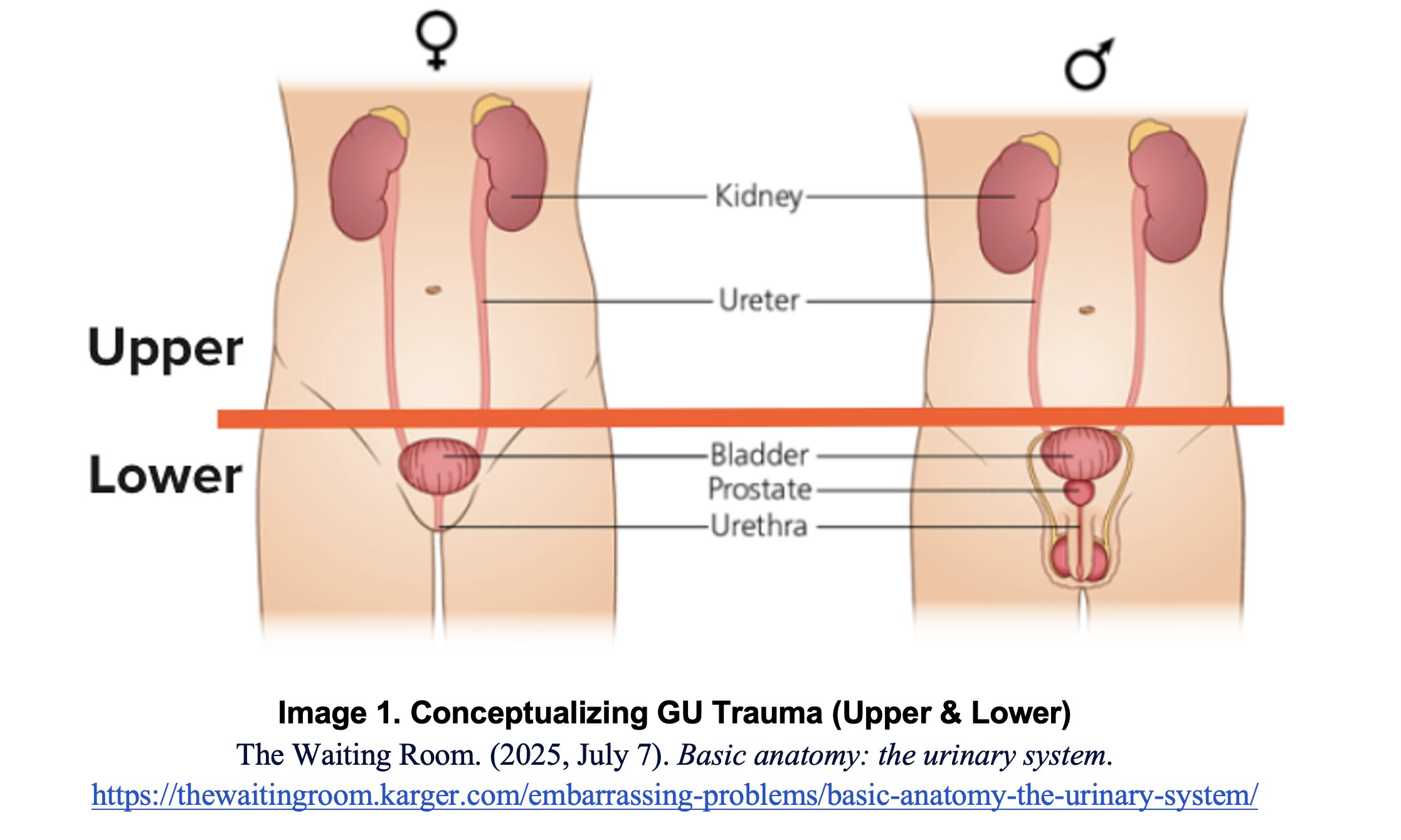

- Helpful to conceptualize GU trauma injury into upper and lower GU injury:

- Upper:

- Renal

- Ureter

- Lower:

- Bladder

- Urethra

- Genitals

Epidemiology

- Urologic organs are involved in about 10% of abdominal traumas.2,3

- Kidneys

- Most commonly injured GU organ.4

- ~5% of trauma victims, predominantly blunt trauma.

- Accounts for 24% of traumatic abdominal solid organ injuries.

- Ureter

- Injuries are rare, about 1% of urologic injuries.

- Bladder

- Injuries occur in 1.6% of blunt abdominal trauma victims.

- Extraperitoneal in approximately 60%, Intraperitoneal in approximately 30%.

- Urethra

- Posterior urethral injuries are almost exclusively associated with pelvic fractures.

- Genitals

- Little data on epidemiology.

- Most common is penile fracture, usually secondary to intercourse.

Approach

- Follow ATLS Trauma assessment algorithm for all patients presenting with concerning traumatic mechanism of injuries.

- Primary Survey: perform all aspects of the primary survey (ABCDEs).

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability

- Exposure

- Always address life threatening injuries first.

- Remember: GU injuries are rarely life threatening.

- Secondary Survey:

- Undress and thoroughly examine all patients.

- Any lower abdominal trauma/tenderness and/or pelvic instability or suspected fractures should raise suspicion for bladder injuries.3,5.

- Flank hematoma may suggest renal injury.3

- Blood found at urethral meatus is considered a urethral injury until proven otherwise.

- Do not place foley catheter until urethral injury is ruled out.

- Inability to urinate should raise suspicion for GU injury.6

Upper GU Trauma

Renal

- Most common injuries are lacerations and contusions.

- Urine studies may reveal microscopic or gross hematuria.

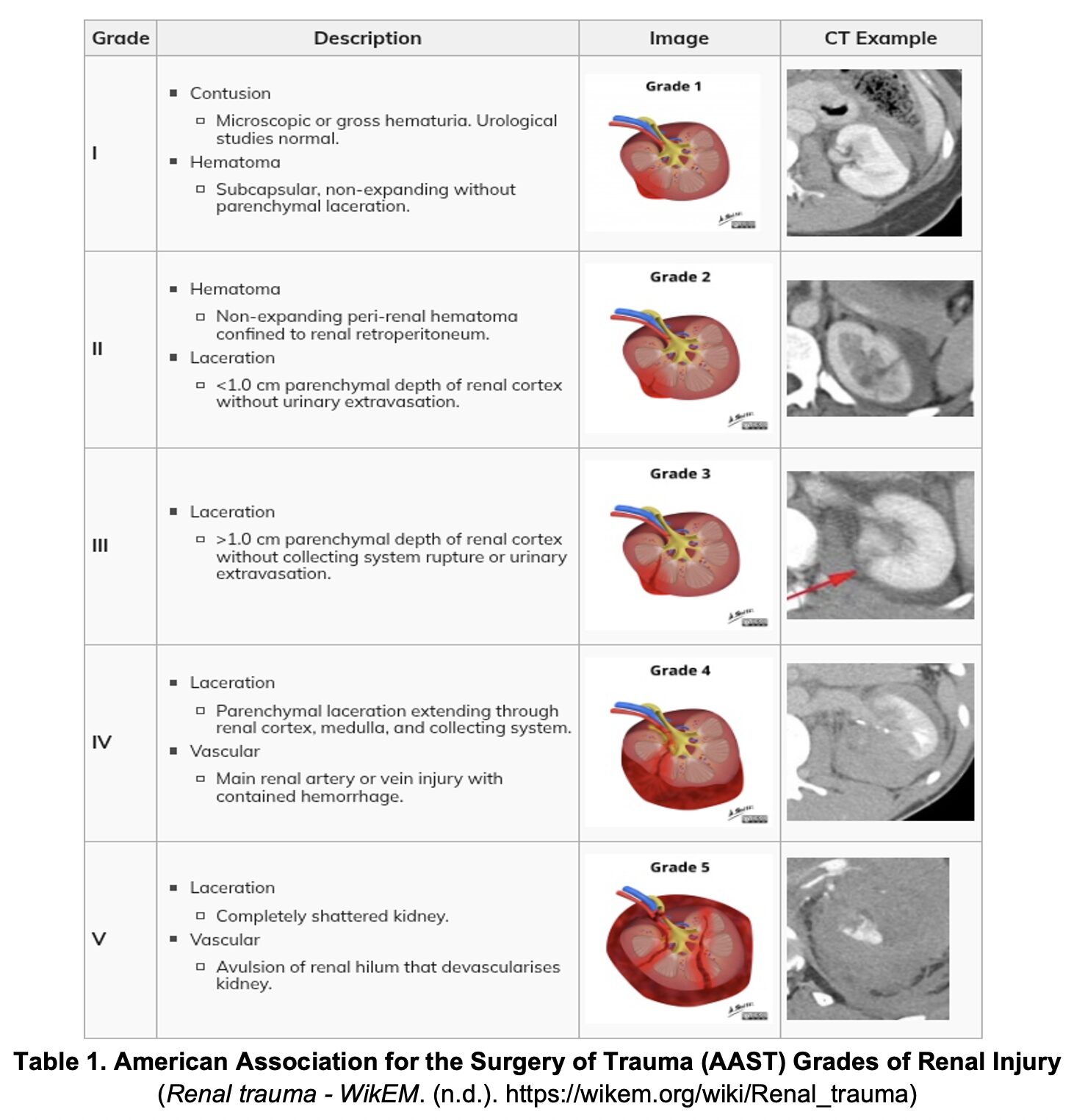

- Renal injuries are graded on severity (Table 1).

- Hemodynamically stable patients of all grades may be treated nonoperatively.

- Still warrant urology consult.

- Likely admission for observation and serial hemoglobin/hematocrit blood draws.

- Any injury higher than Grade 1 requires admission.

- Hemodynamically unstable patients require operative exploration (laparotomy) with urology.3

- Renal Artery Embolization (RAE) with Interventional Radiology is a consideration for stable renal trauma patients and in select cases of patients who are hemodynamically unstable or in cases of renal injury secondary to penetrating trauma.7,8

- Grade I-II injuries are usually self-limited.

- Grade III-V injuries are most likely to benefit from RAE with the goal of preserving renal function and avoiding surgery.

- RAE is considered first line treatment in hemodynamically stable patients achieving an overall 90% success rate.

- For stable patients, multi-phase CT is the diagnostic modality of choice.9

- CT is highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing blunt traumatic injury, including renal injuries.

- Ideally, CT should be a 3-phase study:9

- Arterial phase to assess for vascular injury.

- Nephrographic phase to assess for contusions or lacerations to the kidney.

- Delayed phase to assess for collecting system and ureteric injury.

- Ultrasound is not sensitive or specific.

- Although a FAST exam identifies hemoperitoneum, not all GU injuries will cause hemoperitoneum.

- The kidneys are retroperitoneal which may result in a negative FAST even if they are bleeding.

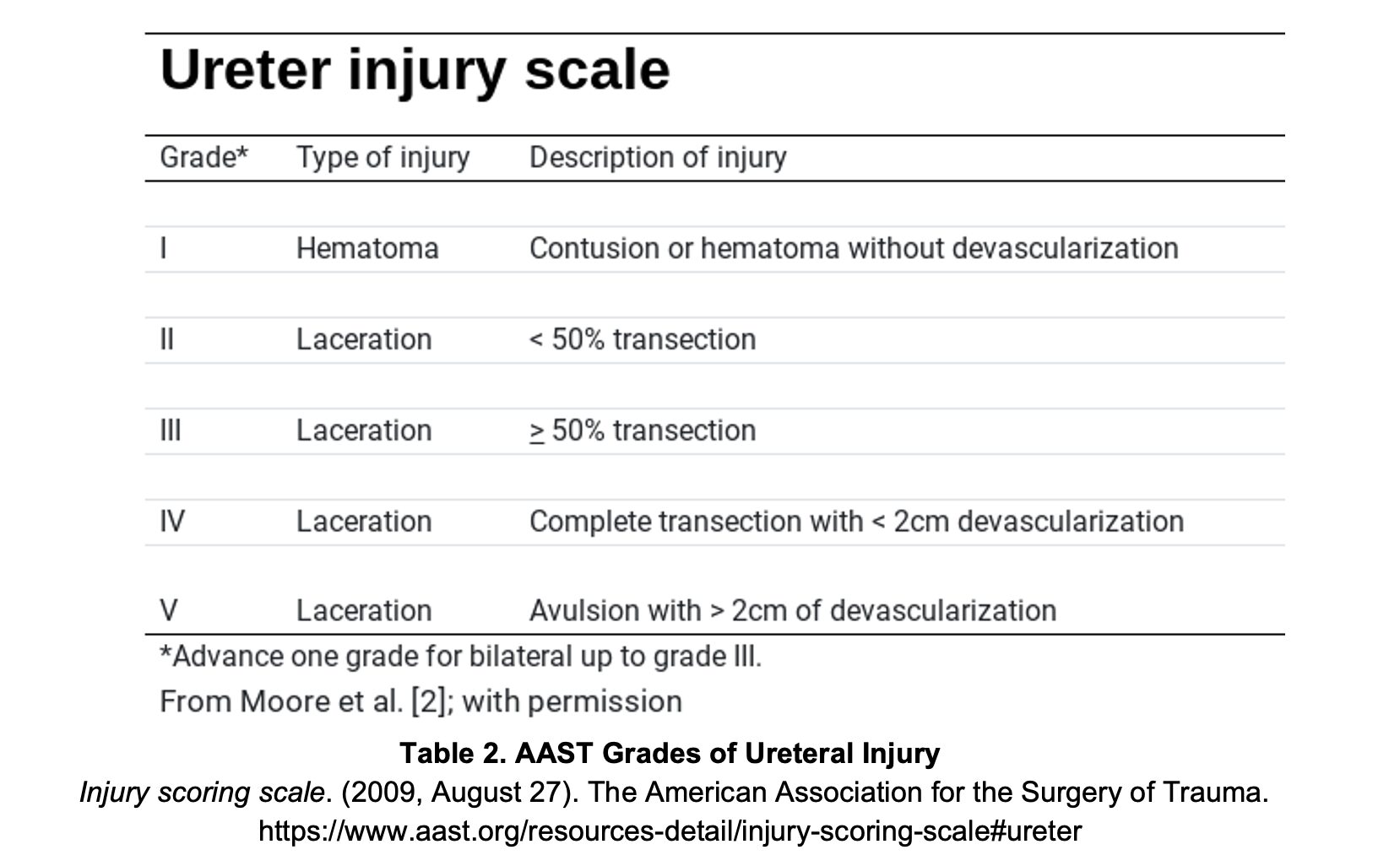

Ureter

- Rarely injured in isolation; usually found in multisystem trauma.

- Surgical management of urethral injuries is dependent on grade, location and patient stability.

- More common in penetrating injuries.

- Urethral injuries are often missed unless specifically evaluated for.

- CT Urography is the diagnostic modality of choice

- Sensitivity and Specificity data is limited due to the lower incidences of these injuries.

- Symptoms are usually nonspecific:

- Hematuria present in ~70%.10

- Delayed signs of occult injury include:3

- Fever / sepsis

- Flank pain

- Ileus

- Complications of missed ureter injury:

- Peritoneal or retroperitoneal urinary leakage

- Perinephric abscess

- Fistula formation

- Ureteral stricture or obstruction

Bladder

- Presenting symptoms of bladder injury include:

- Suprapubic pain

- Blood at meatus

- Urinary retention

- Gross hematuria

- Present in 95% of significant bladder injuries.11

- Bladder injury must be considered present until proven otherwise in the setting of:

- Pelvic fracture with gross hematuria.

- Penetrating injuries of the buttocks, pelvis, or lower abdomen with any hematuria.12

- When concern for bladder injury is high a retrograde cystogram (CT or plain film X-ray) is indicated.

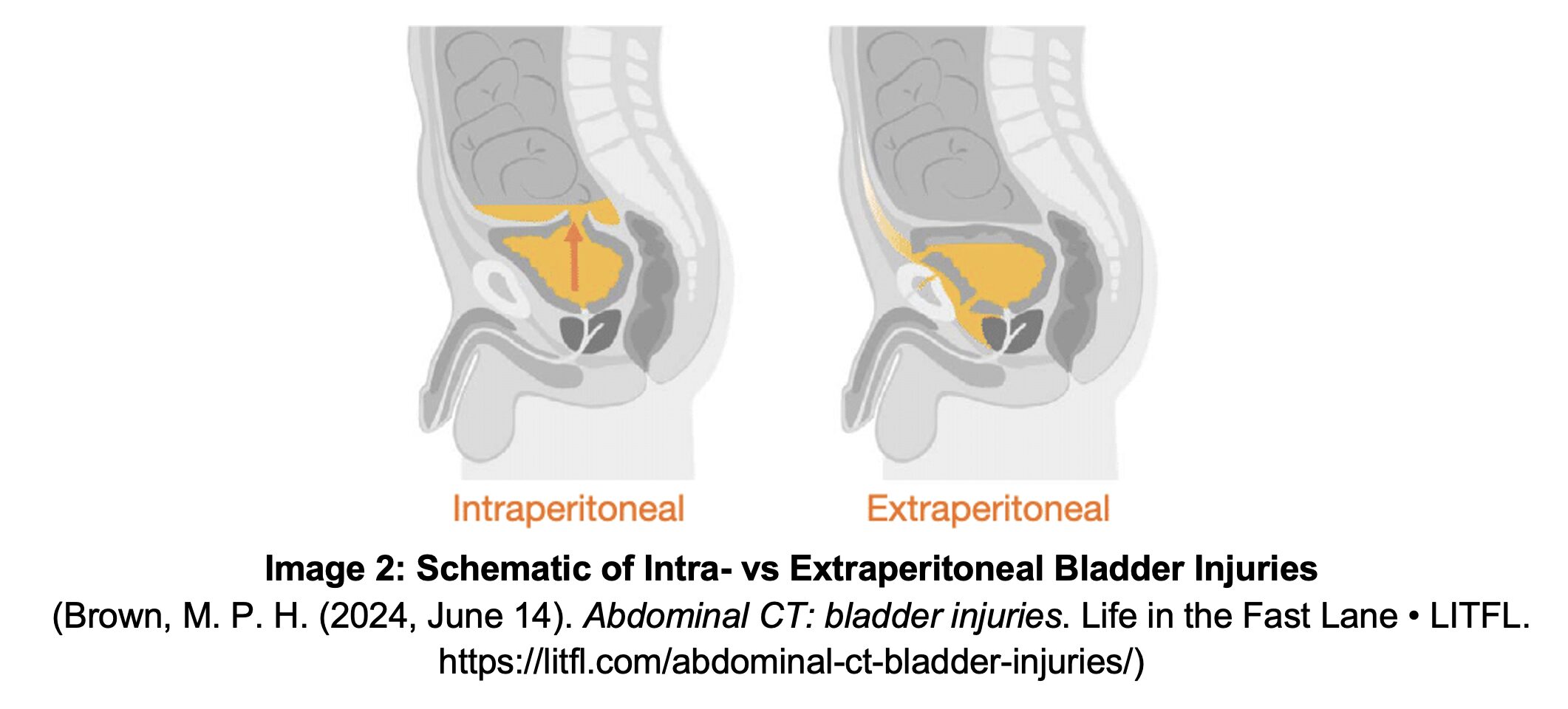

- Management is dependent on type of injury: extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal.

Extraperitoneal Bladder Rupture

- Associated with pelvic fracture and laceration by bony fragments.

- Leakage of urine into the perivascular space; “Tear Drop” pattern on CT imaging.

- Management:

- Non-operative – suprapubic vs urethral (Foley) catheter drainage.

- Consider broad-spectrum antibiotics.13

Intraperitoneal Bladder Rupture

- Associated with compressive force in presence of full bladder.

- Injury to the dome of the bladder results in leakage of urine into the peritoneal space.

- Contrast will outline loops of small bowel within the peritoneum.

- Management

- Operative – OR for laparotomy.

- Consider broad-spectrum antibiotics.13

Lower GU Trauma

Urethra

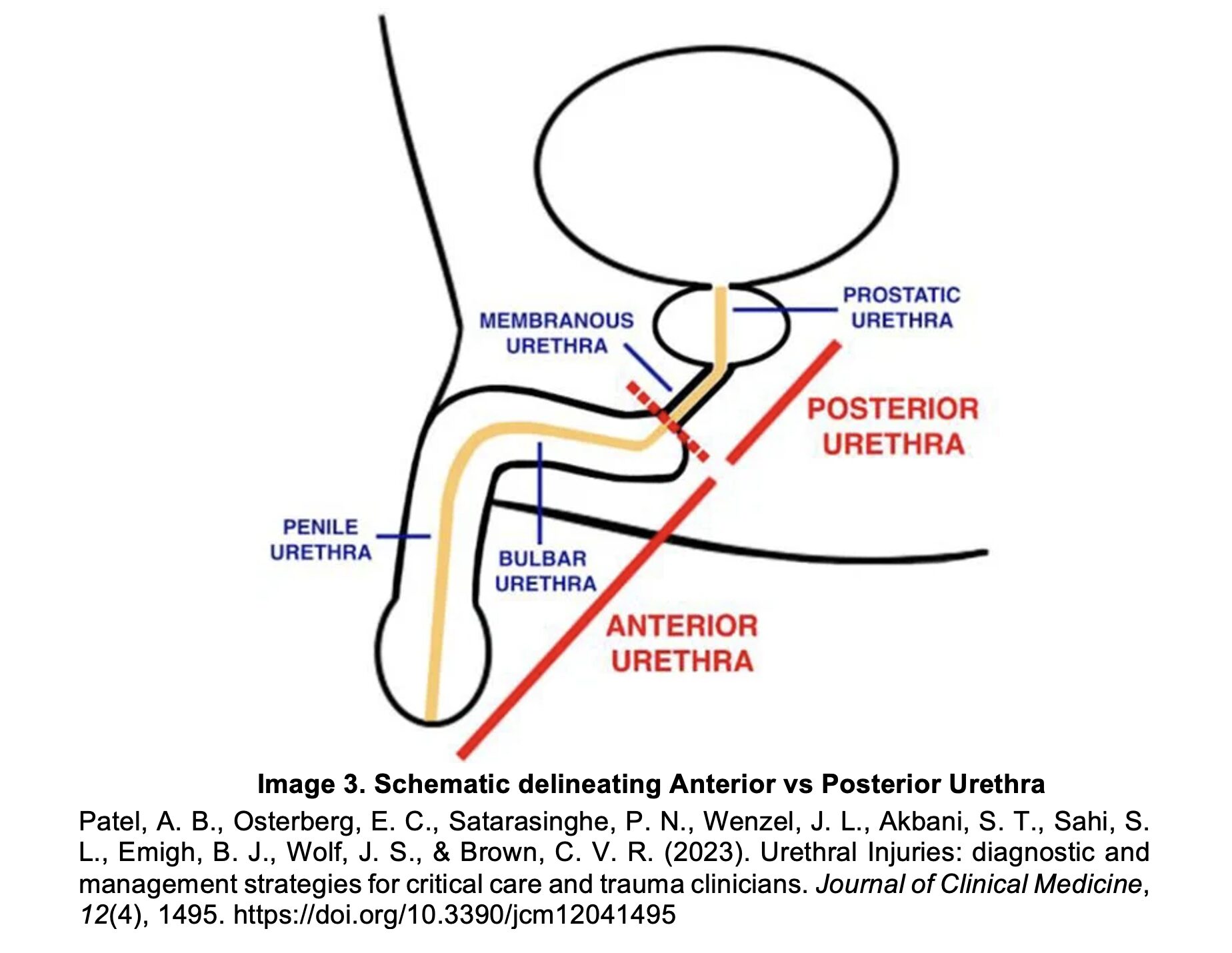

- Anterior Injury:

- Located Anterior to the membranous urethra.

- Common in straddle injuries, self-instrumentation (Foley) injuries.

- Management:

- Surgical exploration (urology) for repair.

- Posterior Injury:

- Located in the membranous and prostatic urethra.

- Common in blunt trauma from massive deceleration.

- Associated with pelvic fractures.

- Management:

- Suprapubic catheter placement.

- Do NOT place a urethral catheter.

- Surgery days/weeks later.

- Blood at urethral meatus in the setting of trauma is a urethral injury until proven otherwise.

- May also present as:

- Vaginal bleeding

- Perineal or scrotal hematoma

- High-riding or detached prostate

- DO NOT PASS URETHRAL FOLEY UNTIL URETHRAL INJURY IS EXCLUDED

- Can cause iatrogenic “false track.3

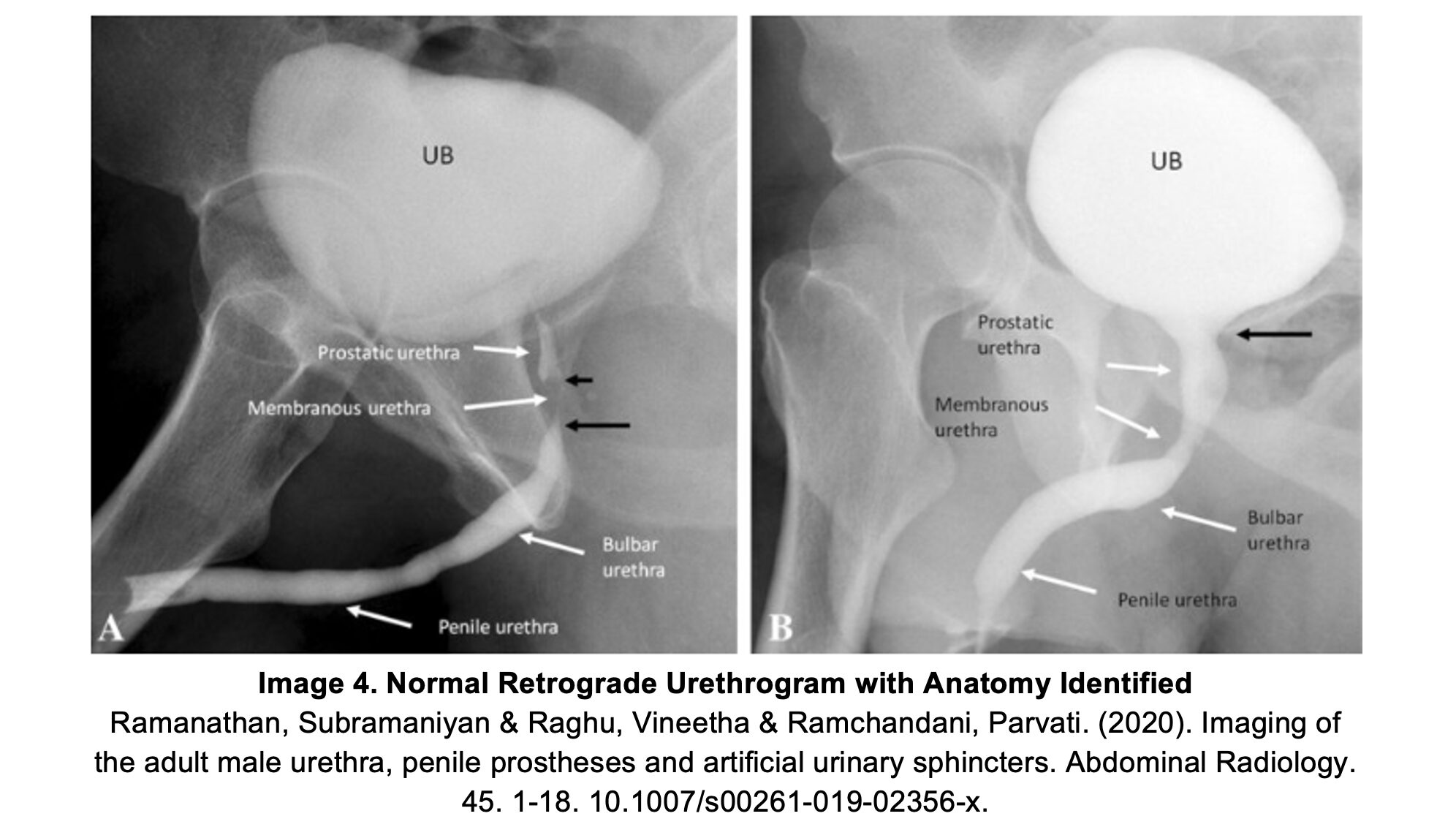

- Retrograde urethrogram (RUG) is diagnostic for urethral injury.

- Standard CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast is likely to miss a urethral injury.

- Procedure:3

- Insert a small caliber (12-14 Fr) Foley or catheter trip 2-4 cm beyond the urethra.

- Inflate balloon with 2-3cm saline to reduce displacement.

- While holding penis upright (perpendicular to the patient) slowly inject water-soluble contrast (Iohexol) 20-60mL.

- Obtain serial anterior/lateral images (X-ray/fluoroscopy) to evaluate for extravasation.

- Continue to slowly inject contrast until contrast fills bladder (or extravasation is detected).

Genitals – Male

- Penile or Testicular Amputation

- Often associated with decompensated psychiatric illness (self-inflicted).

- Urology / Surgical Consult

- Amputation Care:14

- Wrap in Saline Soaked Gauze and place in sterile plastic bag (Bag #1).

- In separate sterile bag place ice and water (Bag #2).

- Place Bag #1 into Bag #2.

- Penile Contusion

- Can’t miss a urethral injury!: (see above)

- Assess for urethral injury:

- Hematuria?

- Can the patient void?

- If no – patient will require foley placement.15

- Most can be managed outpatient with RICE therapy:

- Rest-Ice-Compression-Elevation.

- Assess for urethral injury:

- Can’t miss a urethral injury!: (see above)

- Penile Fracture

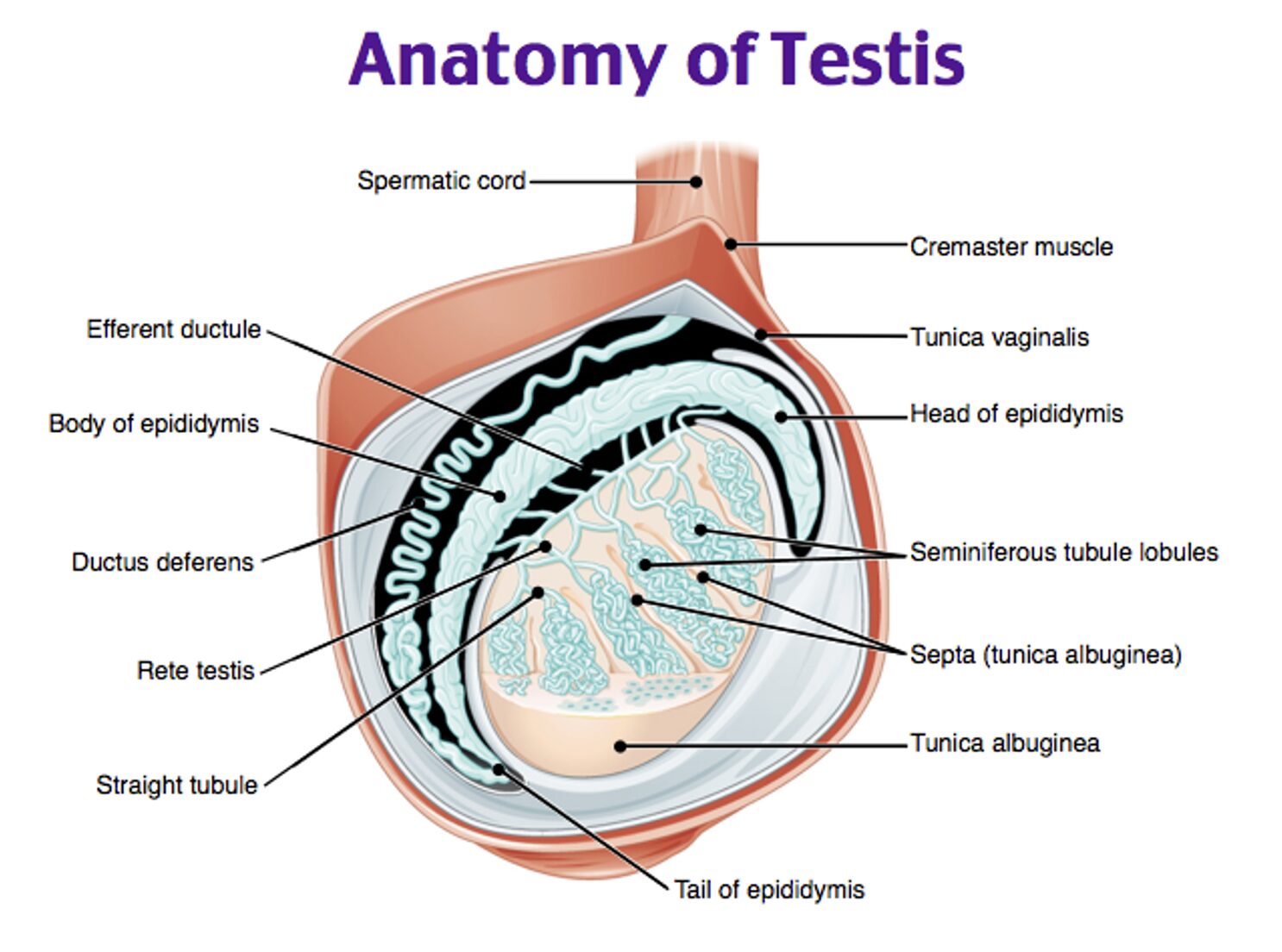

- Tunica albuginea of one or both corpora cavernosa ruptures due to trauma to erect penis.

- Typically occurs with an erect penis during intercourse.

- Patient will often report a “cracking sound” followed by pain, immediate detumescence, swelling, dislocation and obvious deformity.

- Can be associated with urethral rupture and deep dorsal vein injury.

- Can’t miss a urethral injury!

- Urethral injury present in 38% of penile fractures.12

- Evaluate for other trauma.

- MRI or Ultrasound can assist with diagnosis.

- Penile laceration with no fracture can be closed with 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures.

- Surgical exploration is required for most injuries in setting of fracture.

- Traumatic Epididymitis

- Trauma to testicle without evidence of testicular rupture.

- Ultrasound to diagnose.

- Scrotal Support /NSAIDS +/- Antibiotics are the mainstay of therapy.

- Zipper Injury

- Young children

- How to Manage Zipper Injury in ED:16

- Cut clothing around zipper.

- Pain control.

- Consider: Mineral Oil + Lidocaine anesthetic to free penile skin.

- Shears to cut through zipper (horizontally across plane of zipper).

- Avulsed penile skin should not be reapplied (will become necrotic and infected).

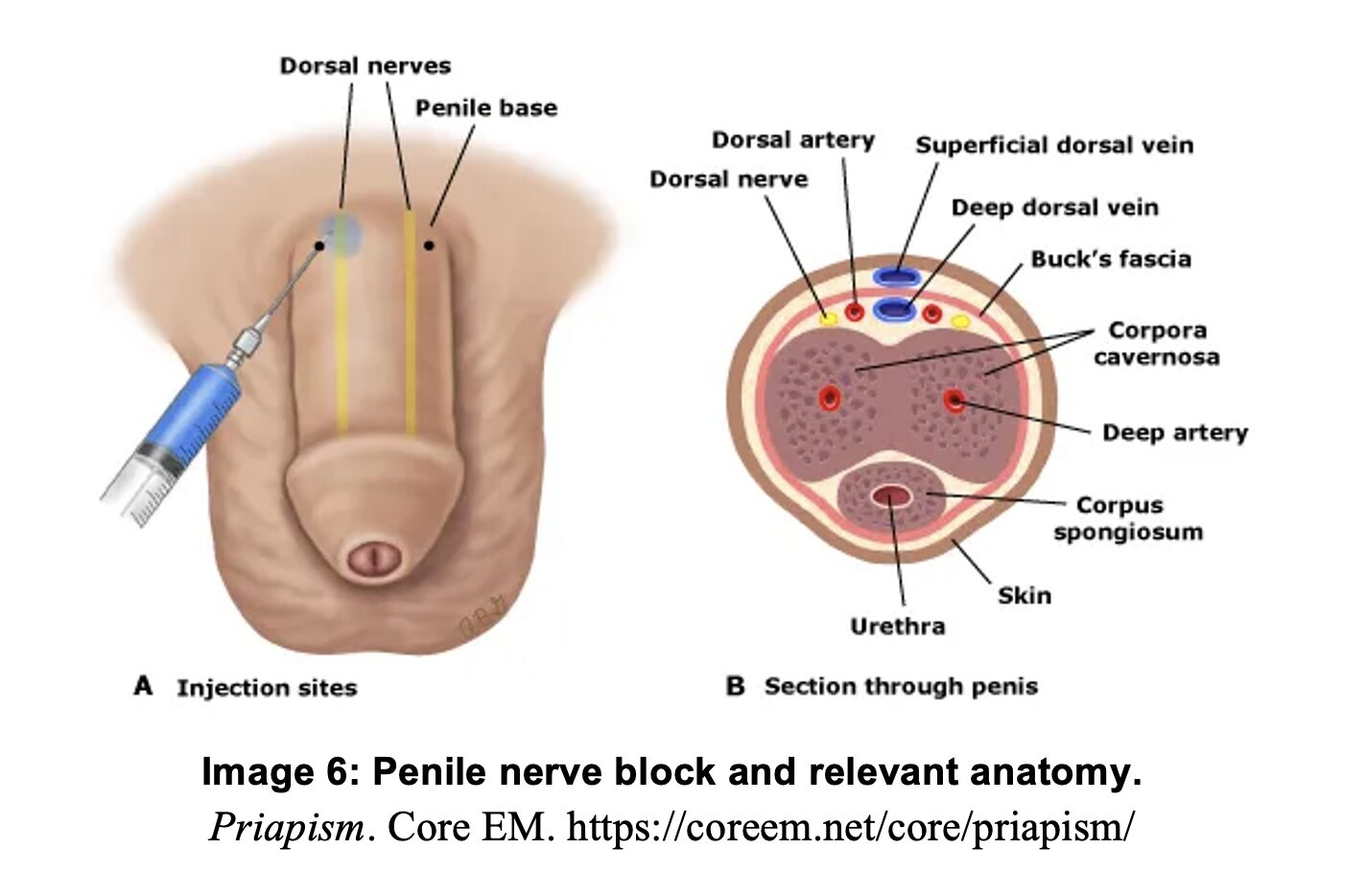

Penile Nerve Block Procedure:17

- Useful for pain control and local anesthetic during procedures such as suturing.

- Procedure:

- Identify dorsal penile base, dorsal nerves run at about the 2 and 10 o’clock positions.

- Clean area with antiseptic solution, apply small wheal of local anesthetic at the 2 and 10 o’clock positions.

- Insert needle just lateral to the midline at 2 and 10 o’ clock positions.

- Advance needle just below Buck’s fascia (a loss of resistance or ‘pop’ may be felt once deep to Buck’s Fascia), avoid deep insertion (target depth ~0.5cm), and aspirate to ensure no vascular injury.

- Inject 2-5 mL of anesthetic agent.

Scrotal Injuries

- Testicular

- Blunt trauma usually due to impingement against symphysis pubis.

- Testicular contusion or rupture is largely dependent on whether tunica albuginea is disrupted.

- Will present as a large, blue, tender scrotal mass (hematocele).

- Ultrasound is diagnostic.18

- Patients with disruption to tunica albuginea should be evaluated by urology/surgery for operative exploration/repair.3

- Penetrating imaging should be evaluated promptly by urology or surgery.3

- Scrotal Skin Lacerations

- Simple Lacerations involving only the skin.

- Can be repaired in the ED with local anesthetic.19

- Close in layers using absorbable for subcutaneous tissue.

- Non absorbable for skin.

- Complex Lacerations involving deeper structures:

- Explore wound to assess for testicular rupture of tunica albuginea injury (or other structures, dartos fascia, tunica albuginea or testicles).

- Urology/Surgery consult for all lacerations involving deeper structures (or equivocal exams).

- Simple Lacerations involving only the skin.

Genitals – Female

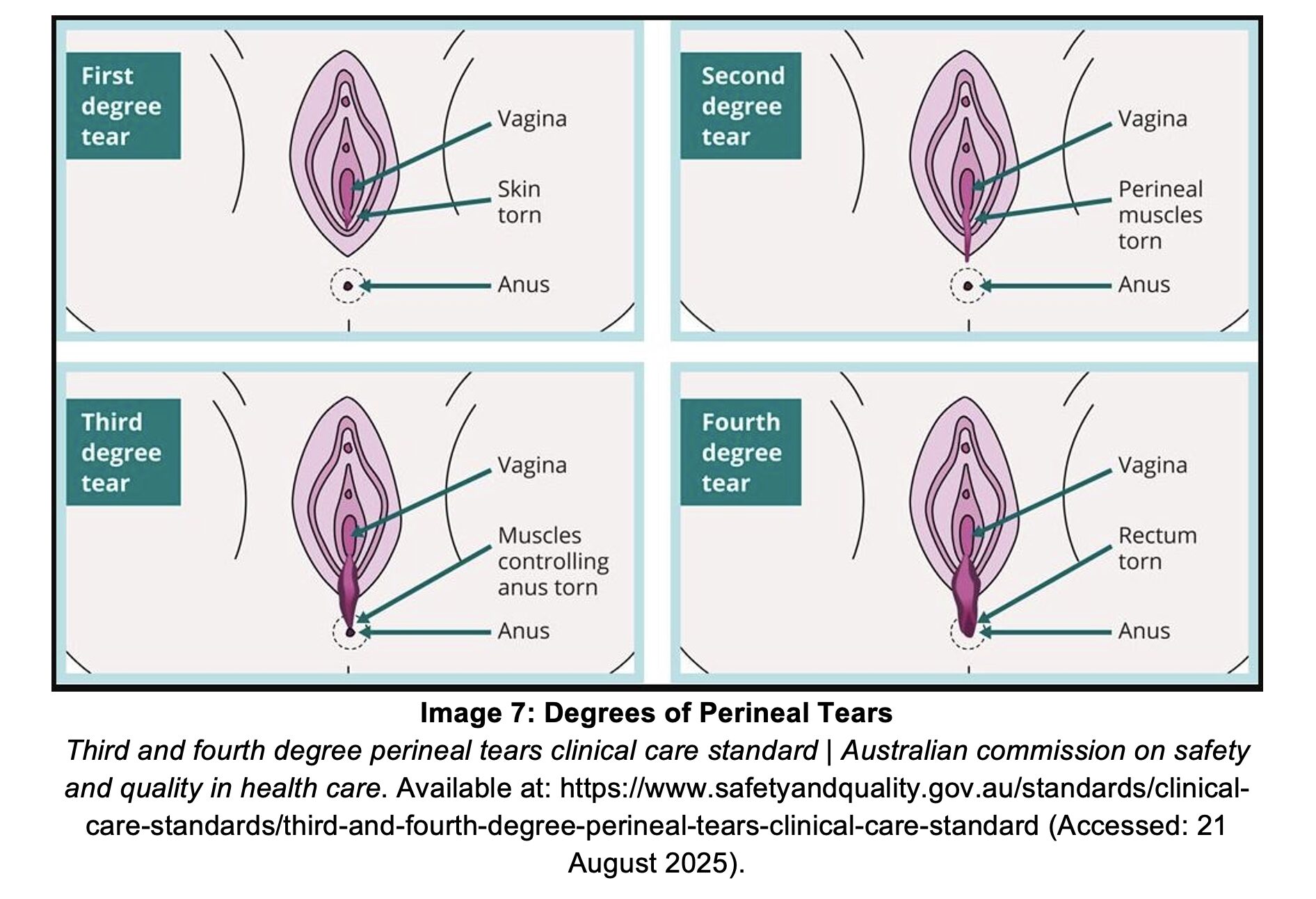

- Perineal Tears:

- 1st Degree: Injury to vaginal mucosa and perineal skin only.

- 2nd Degree: Extends into perineal muscle but not anal sphincter.

- 3rd Degree: Involves anal sphincter.

- 4th Degree: Extends through anal sphincter and rectal mucosa.

- Management:20

- 1st & 2nd Degree: Conservative management.

- Cleanse wound, repair in layers with absorbable sutures, or skin glue.

- 3rd & 4th Degree:

- May require complex, multilayer repair in OR.

- Recommend OB/GYN or colorectal surgical consult.

- 1st & 2nd Degree: Conservative management.

Pearls

- GU trauma is rarely fatal, but can easily be overlooked and lead to high morbidity.

- Blood at the urethral meatus is a urethral injury until proven otherwise.

- Do not pass a foley catheter until injury is excluded via retrograde urethrogram.

- CT is imaging of choice for renal injuries

- Multiphase CT abdomen and pelvis (arterial and venous phase) has sensitivities and specificities of >95%.9, 21

- Ultrasound is neither sensitive nor specific in this setting.

- If a patient has a pelvic fracture, consider:

- Concomitant bladder injury; intraperitoneal vs extraperitoneal.

- Urethral Injury.

- Genital Trauma is rare, but often signals something deeper.

- Penile fracture: consider urethral injury.

- Testicular Trauma: US to evaluate for contusion versus rupture.

- Female perineal trauma: always perform a thorough exam, consider OB/GYN or colorectal consult evaluations as indicated.

- Always consider abuse!

A 33-year-old man fell from a tree while cutting limbs. He sustained significant perineal and genital trauma. Disruption of which of the following structures indicates a testicular rupture?

A) Buck fascia

B) Tunica albuginea

C) Tunica vaginalis

D) Vas deferens

Correct answer: B

The common mechanisms of blunt genitourinary traumas are falls, assaults, motor vehicle-related injuries, and sports-related injuries. Penetrating injuries are usually due to stab wounds or gunshot wounds. Timely diagnosis and appropriate management are aimed at minimizing or preventing kidney dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction. A detailed history should be obtained to determine the time and mechanism of injury. The external genitalia, perineum, and gluteal folds should be thoroughly checked. Blood found on the pants or underwear is an important finding that may suggest genitourinary trauma. A digital rectal examination should be performed to inspect for blood, sphincter tone, or prostate abnormalities (e.g., bogginess or “high riding” prostate). External genital trauma may include penile fractures, scrotal lacerations or avulsions, testicular rupture, or testicular dislocation. A rupture has occurred if the tunica albuginea, the thick fibrous capsule that envelops each testis, is disrupted. The tunica vaginalis fills with blood and forms a hematocele. Diagnosis of testicular trauma is best evaluated with color Doppler ultrasonography. In addition to parenteral analgesia and appropriate tetanus prophylaxis and antibiotics (when indicated), urology should be consulted for testicular blunt or penetrating trauma. Testicular ruptures require immediate repair.

Buck fascia (A) is one of many membranous tissue layers that define the male genitourinary system. It is the deep fascial layer of the penis and does not envelop the testes.

The tunica vaginalis (C) is a potential space that remains intact in testicular rupture. It fills with blood and forms a hematocele.

The integrity of the vas deferens (D) does not define testicular rupture as it is external to the testes.

Further Reading:

- Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Practice management guidelines for the management of genitourinary trauma. Chicago, IL: Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma; 2004. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://www.east.org/education-resources/practice-management-guidelines/details/genitourinary-trauma-management-of

- American Urological Association. Urotrauma guideline. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/urotrauma-guideline

- Joseph M. Urological trauma. In: Johnson W, Nordt S, Mattu A, Swadron S, eds. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. Updated April 28, 2023. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recaJu5DEYdYF4Udy/Urological-Trauma

- Holevar M, DiGiacomo C, Ebert J, et al. Practice management guidelines for the evaluation of genitourinary trauma. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Gomella S. Bladder trauma. In: MSD Manual Professional Edition. Updated January 2025. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- EAU guidelines on urological trauma. Urology Cheatsheets. Published February 2023. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- IR management of splenic and renal trauma. Applied Radiology. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://appliedradiology.com/Articles/ir-management-of-splenic-and-renal-trauma

- Liguori G, Rebez G, Larcher A, Rizzo M, Cai T, Trombetta C, Salonia A. The role of angioembolization in the management of blunt renal injuries: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 2021;21(1):104. doi:10.1186/s12894-021-00873-w

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Urological Trauma: Urogenital Trauma Guidelines. Uroweb. Accessed September 14, 2025. https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urological-trauma/chapter/urogenital-trauma-guidelines

- Armenakas NA, Gomella LG. Ureteral trauma. In: Merck Manual Professional Edition. Updated January 2025. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/genitourinary-tract-trauma/ureteral-trauma

- WikEM contributors. Bladder trauma. In: WikEM. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://wikem.org/wiki/Bladder_trauma

- Wessells H, et al. Penile and genital injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33(1):117-126.

- Morey AF, Brandes S, Dugi DD 3rd, et al. Urotrauma: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2014;192(2):327-335.

- Chang AJ, Brandes SB. Advances in diagnosis and management of genital injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2013;40(3):427-438.

- Van Der Horst C, Martinez Portillo FJ, Seif C, et al. Male genital injury: diagnostics and treatment. BJU Int. 2004;93(7):927-930.

- Rejali N. Unlocking common ED procedures: penile zipper injuries and entrapment. emDocs. Published February 27, 2020. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://www.emdocs.net/unlocking-common-ed-procedures-penile-zipper-injuries-and-entrapment

- Mason J, Sandlin D. Dorsal penile nerve block. In: Swadron S, Nordt S, Mattu A, Johnson W, eds. CorePendium. 5th ed. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. Updated May 31, 2024. Accessed September 4, 2025.https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recSi5S4PGUwHbhXN/Dorsal-Penile-Nerve-Block

- Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Use of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of testicular injuries in blunt scrotal trauma. J Urol. 2006;175(1):175-178.

- Ferlice VJ, Haranto VH, Ankem MK, Barone JG. Management of penetrating scrotal injury. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(2):95-96.

- Arnold MJ, Sadler K, Leli K. Obstetric lacerations: prevention and repair. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(12):745-752. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2021/0615/p745.html

- Ledbetter S, Smithuis R. CT in abdominal trauma. The Radiology Assistant. Published August 2, 2007. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://radiologyassistant.nl/abdomen/acute-abdomen/ct-in-trauma