Authors: Zain Talukdar, MD (Pediatric Resident Physician, University of Chicago); Kimberly Schwartz, MD (Clinical Associate, Pediatrics, Child Abuse Pediatrics) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT), Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 15-year-old female with no reported past medical history presents with lower abdominal pain and possible STI symptoms. She reports living with a “friend” but cannot provide an address, does not attend school regularly, and is accompanied by an adult male who claims he’s “just a family friend” but refuses to leave her side and answers all questions for her. She is alert and oriented but appears fatigued, with mildly matted hair. She avoids eye contact with the clinician and nurse, and her story has changed multiple times since arrival.

What are you concerned about outside of the abdominal pain?

Answer: Sex trafficking

Why Is This Important?

- ED clinicians must recognize risk factors, indicators, and complications associated with trafficking and exploitation (T/E).

- Clinicians are mandated reporters of suspected child abuse and neglect.

- Children are particularly vulnerable due to immature prefrontal cortices, a need for attachment, and limited life experience—worsened by factors like poverty, migration, and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).¹

- An estimated 3.3 million children/adolescents experienced forced labor in 2021, with 1.7 million involved in commercial sexual exploitation.2

- The top three countries of origin of trafficking victims in the U.S.: the U.S. (domestic), Mexico, and the Philippines.3

- Patients rarely disclose T/E; many are medically transient, so referrals are often not followed up.

- In North America, 75% of victims are trafficked domestically. Detection increased by 78% (2019–2022), while convictions decreased by 28%.4

- No robust national prevalence data on sex or labor trafficking exists in the U.S.

Important Terms

- Trafficking: Involves coercion, fraud, or force for labor or sex, including involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.

- Child sex trafficking: Recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a minor for commercial sex (consent is irrelevant under U.S. law).5

- Child labor trafficking: Forced/coerced labor of minors in violation of labor laws.5

- Domestic trafficking: T/E occurring within the victim’s home country.

- Transnational trafficking: T/E across international borders.

- Enmeshment: Blurring boundaries to foster emotional dependence on the trafficker.

- Entrapment: Control tactics such as financial control, isolation, drug addiction, pregnancy, emotional blackmail, and manipulation.5

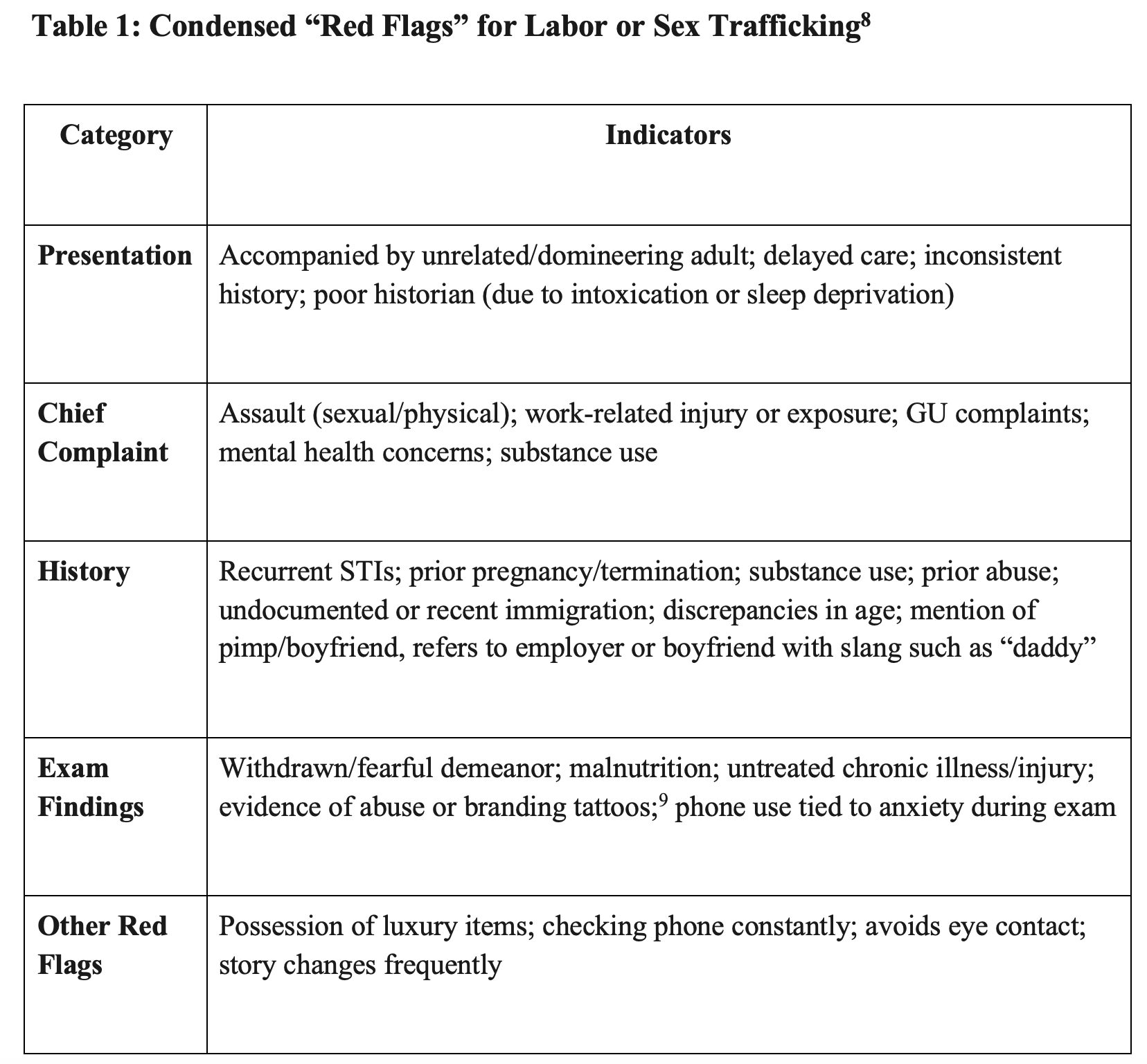

How to Identify/Evaluate for Trafficking

Patient Factors

- Fear of deportation or retaliation

- Belief they are not being exploited

- Females are more often victims of sex trafficking; males more commonly trafficked for labor.6

- LGBTQIA+ youth, undocumented individuals, or those experiencing homelessness are more vulnerable

- Involvement with legal system, child protective services, foster care

Relationship Factors

- Victims may be recruited by friends, family, community members, or strangers.

- Control exerted via blackmail, emotional manipulation, or threats.

- Influence of a trafficker who may provide false information or attend the visit (sometimes recording it or having an active phone call during encounter).6

- Common dynamics include enmeshment and ⁷

Community Factors

- Areas with high poverty or crime

- Recent immigration from unstable regions, parts of the world with weak recognition of child rights/labor rights

- Lack of tolerance for gender identity or sexual orientation in community

History / Physical Exam

- Note any temporal gaps in HPI (possible drugging/sedation).

- Assess immediate safety and mental health.

- Perform a HEADSSS exam (Home, Education/Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicidality, Safety), focusing on:

- Housing instability

- Work conditions

- Access to school or guardianship

- Ideally speak to patient separately without anyone else in room

- Explain each step clearly to reduce re-traumatization and restore patient control.

- Document injuries carefully, noting age and appearance. Include photos in EMR.

- Document tattoos, particularly those suggestive of ownership or branding.9

- Genital exam caveats:

- Normal anogenital findings do not rule out sexual assault.10

- For prepubertal children: exam limited to external genitalia/anus unless concern for active bleeding or other internal injuries.

- For adolescents: external exam + bimanual/pelvic exam as clinically indicated.

- Always keep trauma-informed care, patient assent, and appropriate chaperoning in mind.11

- If sexual abuse is suspected, consider a forensic evidence kit (ideally within 24 hours of assault for prepubertal children and 72 hours for adolescents for optimal DNA recovery rates, but can be within 5-7 days of assault).10,11

Screening Tool

- Short Screen for Child Sex Trafficking (SSCST): A concise, validated tool that asks targeted yes/no questions (e.g., history of running away, physical assault, trading sex for necessities, forced sexual activity).12

Evaluation

Order testing based on clinical scenario or risk factors:

- STIs: gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas (NAAT), syphilis (RPR), HIV (Ag/Ab)

- Misc: Hep B/C, Utox, UA, iron, vitamins, CBC, metabolic panel

- Infectious diseases: TB, MRSA, COVID

- Consider endemic infections from home region if recently immigrated, involve infectious disease team as needed15

- Offer contraception if indicated; involve adolescent gynecology as needed

- Consider transfer to a capable center if your center does not have child abuse pediatrics, or if the patient requires multidisciplinary coordination of care not available in your ED (legal services, mental health services, immigration services, social work)

Documentation: Best Practices

- Use objective, nonjudgmental language (avoid terms like “claims” or “alleges” unless quoting).

- Clearly record injuries, suspicious findings, and demeanor (e.g., “appeared anxious when an adult was present”).

- Note any discrepancies in history or behavior that raised concern.

- Avoid detailed speculation or premature conclusions; document facts, not assumptions.

- Document:

- Presence and behavior of accompanying adult

- Patient’s affect, engagement, and cooperation

- Interpreter use (and language spoken)

- Whether separation from guardian occurred

- Any referrals made (social work, law enforcement, CPS, etc.)

- If photos or forensic kits were performed or deferred

- Check with your hospital and state laws/policies for any specific information required.

Example phrasing:

“Patient arrived with an adult male who declined to provide relationship; adult answered most questions. Patient avoided eye contact and appeared fearful. Interpreter used for Spanish. Social work notified. Patient separated for interview. GU exam normal. STI testing sent.”

Clinical Pearls:

- If child seems uncomfortable by having clinician of opposite sex, then consider history gathering from a different clinician.

- Disconnect video or audio call during the examination as a matter of practice and procedure.

- Discreetly provide resources to child outside of view and hearing of adult, for when patient wants to take advantage (can text BeFree, see below).

A 17-year-old girl presents to the emergency department with abdominal pain. The history is challenging even in her native language, so her young adult friend in the room answers most of the questions but reports no fevers, vomiting, diarrhea, or other ill symptoms. The friend does not want to leave the patient alone for a personal interview because the patient has only recently arrived from a foreign country. Other than tachycardia of 120 bpm, her vital signs are within normal limits. She is fearful on exam and has active guarding on palpation of her lower abdomen. She has a positive pregnancy test result. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step to care for this patient?

A) Contact law enforcement

B) Draw serum abdominal labs

C) Interview the patient alone

D) Obtain a pelvic ultrasound

Correct answer: C

Human trafficking refers to forced labor or sexual exploitation of people. It can involve sex work, the creation of pornography, or forced marriage. The patients will not identify as trafficked and may present with a parent or person who is unaware of the trafficking. Those who are trafficked are controlled by some other person, usually out of fear or debt. They can feel threatened with violence, guilt, shame, humiliation, or arrest. Many of them have committed some crime and are also fearful of law enforcement. They often present with a wide range of concerns, including physical or sexual assault, sexually transmitted infections, need for HIV testing, pregnancy, abortion complications, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, suicidal behavior, aggression, and somatization.

When the trafficker or a trafficker’s employee is present, they may refuse to leave the child alone, be in a hurry to leave, or want to control the conversation. It is important to establish a safe space for those who are potentially being trafficked. Universal department protocols to discuss relationship abuse alone with adolescents are important to empower clinicians to provide this safe moment to identify potential trafficked individuals. It also allows the clinician to determine the source of the patient’s fear (e.g., the above patient may fear deportation and not a trafficker). When this discussion is done appropriately and sensitively, the team can use this moment to reaffirm the patient’s rights, discuss the limits of confidentiality, ensure nonjudgment, and assess safety concerns. They can also disclose sensitive results, such as a positive pregnancy test result. Some people who are being trafficked may not be ready to discuss it out of fear of retaliation against friends or family, so these universal protocols can inform them to return to use this safe moment on a subsequent visit. Adolescents may also be more willing to disclose abuse to friends, and when done universally, this allows them to share the caring nature of the emergency department with others.

Whenever trafficking is suspected, it is appropriate to contact law enforcement (A) and child protective services, but when done before a separate interview, it may dissuade the use of the emergency department if patients who are not trafficked are fearful of law enforcement.

Drawing serum abdominal labs (B) is appropriate in this patient, but a confidential interview may lead to more specific and complete testing such as HIV and hepatitis C.

This patient may need a pelvic ultrasound (D) depending on information obtained in a confidential interview and further examination (e.g., vaginal bleeding, discharge, cervical motion tenderness).

Further Reading:

Resources

- National Children’s Alliance – CAC Coverage Map

- CDC Immigrant Health Toolkit

- National Human Trafficking Hotline

Call 1-888-373-7888 or text HELP or INFO to BeFree (233733) - NHTTAC: National Human Trafficking Training & Technical Assistance Center

- DHS Blue Campaign – Red Flags Card

References

- Baird K, Connolly J. Recruitment and Entrapment Pathways of Minors into Sex Trafficking in Canada and the United States: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(1):189–202.

- International Labour Organization, Walk Free, International Organization for Migration. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage. Geneva, 2022

- United States Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Trafficking in Persons Report 2024.https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2024/GLOTIP2024_BOOK.pdf

- U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), 22 U.S.C. § 7102(11). https://www.justice.gov/criminal/criminal-ceos/child-sex-trafficking

- Cindy C, COMMITTEE ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT; The Evaluation of Suspected Child Physical Abuse. Pediatrics May 2015; 135 (5): e20150356. 10.1542/peds.2015-0356

- Reid JA. Entrapment and Enmeshment Schemes Used by Sex Traffickers. Sexual Abuse. 2016;28(6):491–511

- Jordan G et al, COUNCIL ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT, COUNCIL ON IMMIGRANT CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH; Exploitation, Labor and Sex Trafficking of Children and Adolescents: Health Care Needs of Patients. Pediatrics January 2023; 151 (1): e2022060416. 10.1542/peds.2022-060416

- Fang S, et al. Tattoo recognition in screening for victims of human trafficking. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(10):824–827

- Smith TD, et al. Anogenital findings in pediatric examinations for sexual abuse. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31(2):79–83

- Adams, J et al,. Updated guidelines for the Medical Assessment and care of children who may have been sexually abused. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 29(2), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.01.007

- Greenbaum VJ, et al. A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(1):33–37

- Panlilio CC, Dierkhising CB, Richardson J, Runner J. Evaluating and Validating the Classification Accuracy of a Screening Instrument to Assess Risk for Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Child Welfare-Involved Children and Adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2022 Jul-Aug;137(1_suppl):73S-82S. doi: 10.1177/00333549211065523. PMID: 35775915; PMCID: PMC9257490.

- Basson D. Validation of the Commercial Sexual Exploitation–Identification Tool (CSE-IT). WestCoast Children’s Clinic; 2017. Available from: https://www.westcoastcc.org/cse-it/cse-it-research

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for the U.S. domestic medical examination for newly arriving refugees.

- Greenbaum J et al, COUNCIL ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT, COUNCIL ON IMMIGRANT CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH; Exploitation, Labor and Sex Trafficking of Children and Adolescents: Health Care Needs of Patients. Pediatrics January 2023; 151 (1)

- Wallace C, et al. Share our stories: healthcare experiences of child sex trafficking survivors. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;112:104896

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of children: subject review.Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):186–191

- Jordan Greenbaum, Dana Kaplan, Nia Bodrick, Council on Child Abuse and Neglect, Section on Global Health; Human Trafficking and Exploitation of Children and Adolescents: Policy Statement. Pediatrics July 2025; 156 (1): e2025072214. 10.1542/peds.2025-072214

- CDC. “Refugee Health Domestic Guidance.” Immigrant and Refugee Health, 21 May 2024

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “Indicators of Human Trafficking.” Department of Homeland Security, 17 Oct. 2018, www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/indicators-human-trafficking.