Today on the emDOCs cast with Brit Long, MD (@long_brit), we’re back with Part 2 on upper GI bleeding. Today we cover endoscopy, other interventions for bleeding cessation, intubation, and risk scores. Please see Part 1 for some background, NG tube lavage, blood product transfusion, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), prokinetic agents, somatostatin analogues, and antibiotics.

Episode 126: Upper GI Bleeding Evidence and Controversies Part 2

When is endoscopy recommended?

- Upper GI endoscopy key diagnostic modality with high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing source of bleeding. Integral to achieving hemostasis and preventing rebleeding. Thus, consult GI for admitted patients with UGIB.

- Risks of endoscopy: aspiration, GI perforation, increased bleeding, and adverse events to sedation.

- Current data suggest endoscopy within 24 hours associated with reduced in-hospital mortality, shorter LOS, and reduced costs in those with non-variceal UGIB.

- Endoscopy within 12 hours has demonstrated conflicting results.

- 2020 study evaluated endoscopy within 6 hours of GI consultation compared with endoscopy within 24 hours in those with acute UGIB, hemodynamic stability, and Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS) ≥ 12. No difference in mortality, but only a quarter underwent endoscopy within 6 hours, and there were no patients who were hemodynamically unstable.

- Another RCT evaluating endoscopy within 12 hours compared with after 12 hours for those with UGIB due to confirmed bleeding ulcer found no decrease in bleeding or mortality.

- Large prospective study with 12,601 patients with UGIB associated with peptic ulcers found higher in-hospital and 30-day mortality in patients undergoing endoscopy within 6 hours, particularly in those who were hemodynamically unstable or had an American Society of Anesthesiologists score ≥ 3.

- Data for variceal UGIB differ.

- Meta-analysis of 9 studies found patients with variceal UGIB undergoing early endoscopy within 12 hours had reduced mortality compared to delayed endoscopy after 12 hours, with no difference in rebleeding.

- Guidelines: ACG recommends performing endoscopy within 24 hours of admission or patient presentation in patients with non-variceal bleeding who are hemodynamically stable; ESGE guidelines and ICG recommend performing endoscopy within 24 hours but after resuscitation in those with non-variceal bleeding.

- ACG and ESGE guidelines do not recommend urgent endoscopy (≤12 hours) in patients with non-variceal UGIB, as there is no improvement in patient-centered outcomes. ICG does not make a recommendation before or against endoscopy within 12 hours in those with non-variceal bleeding.

- Guidelines for those with variceal bleeding differ; these patients should undergo endoscopic evaluation within 12 hours. In patients with variceal bleeding, guidelines recommend endoscopy as soon as possible after resuscitation.

- Must resuscitate prior to endoscopy.

- Take-home: Data and guidelines suggest that while endoscopy should be obtained within 24 hours in those with non-variceal UGIB, emergent resuscitation prior to endoscopy is necessary, along with GI consultation in the ED. In variceal bleeding, endoscopy within 12 hours (or sooner) is recommended after resuscitation. Evidence suggests that a normal hemoglobin or platelet count is not necessary prior to endoscopy. Antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, and a defined INR threshold should not be used as contraindications.

What are other interventions beyond endoscopy?

- For UGIB that fails other therapies including endoscopy, particularly in those with peptic ulcer disease, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) or surgery may be necessary.

- Meta-analysis including 13 studies comparing TAE versus surgery in patients with UGIB who failed endoscopy found no difference in mortality (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50-1.18), but fewer major complications (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.30-0.67) and reduced LOS (8 vs. 16 days) in TAE. There was higher risk of bleeding with TAE (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.77-3.36).

- TAE is a viable option for control of UGIB.

- If interventional radiology available, consult both IR and surgical specialist. Specific modality should be based on the hemodynamics, local expertise, and patient comorbidities. If TAE is an option, CTA can help to assist with localization of the bleeding. With appropriate localization, TAE successful in approximately 95% of patients.

- For patients with variceal bleeding who continue bleeding despite medical therapy while waiting endoscopy, a balloon tamponade device can be used for short-term bleeding control; there are complications and a risk of rebleeding when the balloon is deflated.

- Three balloon tamponade devices: Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (with a gastric and esophageal balloon and single gastric suction port), Minnesota tube (gastric and esophageal balloon with esophageal and gastric suction ports), and Linton-Nachlas tube (gastric balloon).

- These devices are effective in 30-90% of patients with variceal bleeding.

- Patients should be intubated prior to balloon placement.

- After the device is placed, it can remain in place for 24 hours, but gastric balloon needs to be deflated every 12 hours to assess for rebleeding. If bleeding recurs upon deflation, the balloon can be reinflated.

- Balloon tamponade is only a temporizing measure; relative contraindications include recent esophageal or gastric surgery and esophageal stricture.

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an option for patients with severe, continued variceal bleeding and functions as a surgical portacaval shunt. 90-100% success rate in decreasing bleeding, but may increase the risk of encephalopathy.

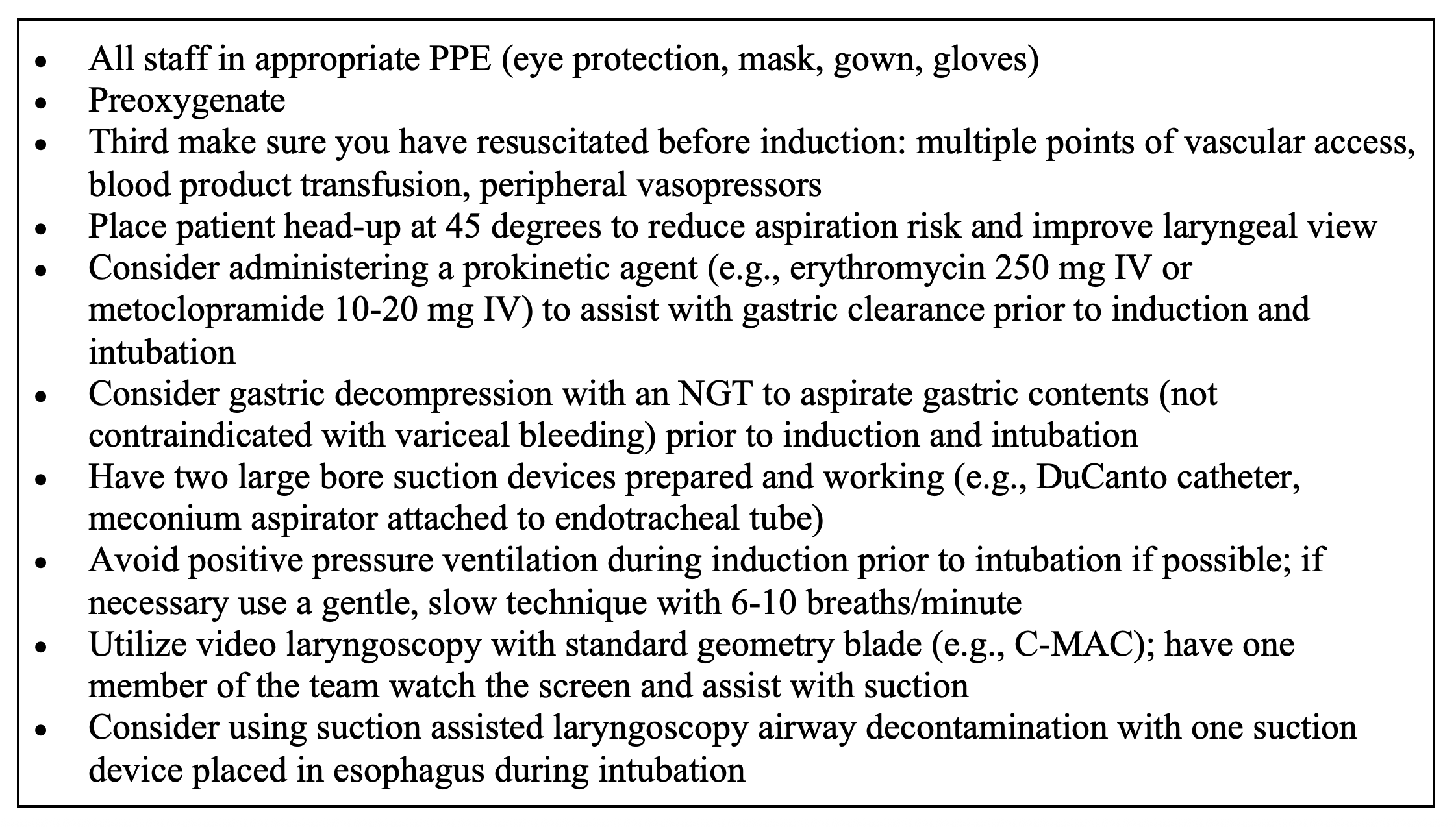

What airway considerations are necessary in those with UGIB?

- Challenging airway. If y intubating, must manage complications like an obstructed view due to the blood or vomit; risk of aspiration, hemodynamic instability, comorbidities, and blood or body fluid exposure.

- Avoid endotracheal intubation if at all possible. Prophylactic intubation in UGIB is associated with greater risk of mortality, pneumonia, hospital LOS, and cost.

- ESGE recommends against routine endotracheal intubation prior to upper endoscopy.

- Intubation necessary in those with respiratory distress/failure, decreasing level of consciousness, continued ongoing hematemesis, inability to adequately control the airway, high risk of continued deterioration, aspiration, and need for further intervention like a GI tamponade device or endoscopy).

- Resuscitate prior to intubation and have double setup for cricothyrotomy.

Table. Approach for endotracheal intubation in those with UGIB.

Which decision tools are effective at risk stratifying patients with UGIB?

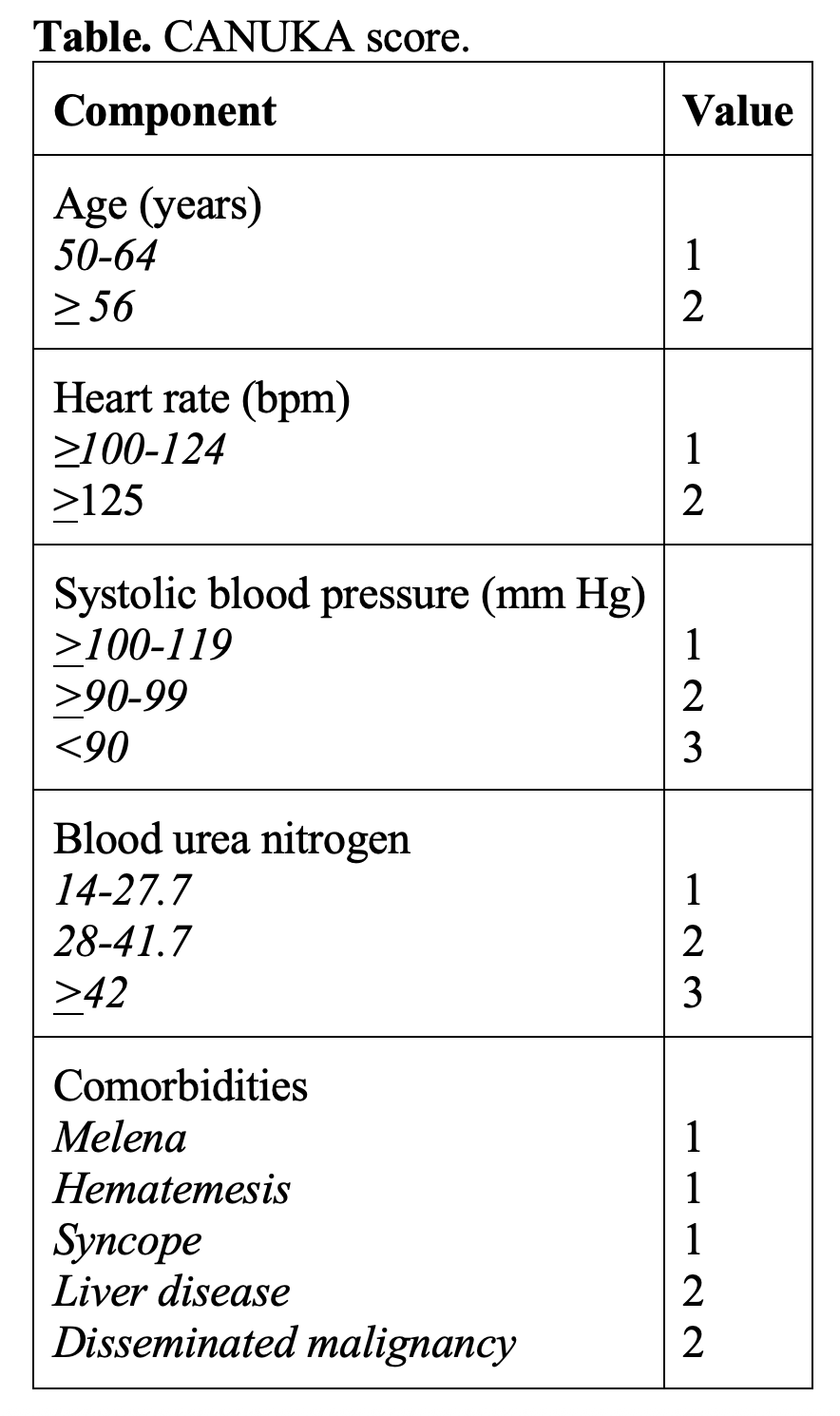

- Tools: GBS, AIMS65 score, ABC score, Canada–United Kingdom–Adelaide (CANUKA) score, and the Rockall score.

- Two versions of the Rockall score: pre-endoscopy and post-endoscopy; pre-endoscopy score is the most relevant for the emergency clinician and includes age, shock, and comorbidities.

- GBS is the most commonly used score and have been validated several times. GBS ≤ 1 over 98% sensitive in predicting low risk UGIB. Multiple studies comparing GBS with other scores suggest GBS is more accurate in determining who is low risk and predicting mortality and need for in-hospital intervention. Modified version of GBS removes melena, recent syncope, history of liver disease, and the presence of heart failure. Several studies suggesting similar accuracy between the original and modified versions of GBS.

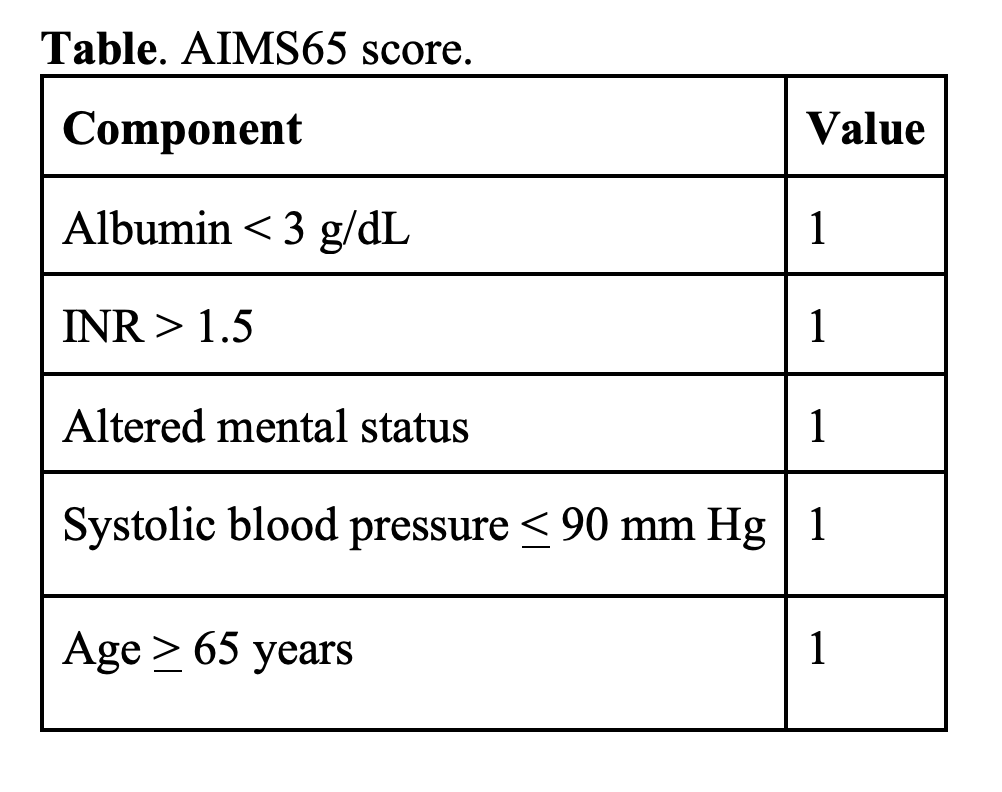

- AIMS65 was derived in 2011 to predict mortality and can also be used prior to endoscopy. One study suggests AIMS65 may be better at predicting in-hospital mortality, intensive care unit admission, and hospital LOS, while the GBS is better at predicting the need for transfusion.

- ABC score has demonstrated good performance in predicting mortality.

- Most recently evaluated score is the CANUKA scoring system, derived in 2019. A second study evaluating the CANUKA score found those with a score < 4 had no adverse events, and no patient with a score < 6 died. Third study found GBS ≤ 1, modified GBS of 0, and CANUKA ≤ 2 had high sensitivity in determining low risk, with no patient deaths.

- 2016 systematic review compared the GBS, Rockall, and AIMS65 scoring systems. GBS score had better predictive value in determining low risk for 30-day adverse events.

- 2023 meta-analysis comparing risk scores for UGIB included 38 studies evaluating the GBS, clinical Rockall score, CANUKA, AIMS64, and ABC score. GBS score with a threshold of ≤ 1 was the best discriminator in predicting low risk (including mortality; rebleeding; and need for endoscopic, surgical, or radiologic intervention).

- Guidelines: ACG, ESGE, and ICG suggest using a GBS score of ≤ 1 over other scores to identify UGIB patients at very low risk of mortality or rebleeding and who may be appropriate for outpatient management.

- Do NOT rely on these scores alone.

- Severe or recurrent bleeding, hemodynamic instability, significant comorbidities, suspected high risk bleeding sources (e.g., varices, ulcer, Dieulafoy’s lesion), or inability to follow up should be admitted.

- Consider discharge with follow up if these are not present and the patient can be stratified as low risk (e.g., GBS of ≤1).

Summary:

- Endoscopy is recommended within 24 hours for those with non-variceal bleeding for diagnosis and management, though this should be completed sooner in those with variceal bleeding.

- If endoscopy fails to achieve hemostasis, TAE or surgical intervention may be necessary.

- Endotracheal intubation may be necessary in select patients but is not recommended routinely.

- GBS ≤ 1 suggests the patient is at low risk of adverse events, but these risk scores should never replace clinical judgment.

References:

- Kamboj AK, Hoversten P, Leggett CL. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Etiologies and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Apr;94(4):697-703.

- Stanley AJ, Laine L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ. 2019 Mar 25;364:l536.

- Abougergi MS, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. The in-hospital mortality rate for upper GI hemorrhage has decreased over 2 decades in the United States: a nationwide analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Apr;81(4):882-8.e1.

- Alali AA, Barkun AN. An update on the management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2023 Mar 20;11:goad011.

- Laine L. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1198.

- Fouad TR, Abdelsameea E, Abdel-Razek W, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Egyptian patients with cirrhosis: Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep;34(9):1604-1610.

- Cooper AS. Interventions for Preventing Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in People Admitted to Intensive Care Units. Crit Care Nurse. 2019 Apr;39(2):102-103.

- Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, et al. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40(3):652-659.

- Laine L, Barkun AN, Saltzman JR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Upper Gastrointestinal and Ulcer Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 May 1;116(5):899-917.

- Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021 Mar;53(3):300-332.

- Barkun AN, Almadi M, Kuipers EJ, et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 3;171(11):805-822.

- Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 Feb;90(2):206-10.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. Initial management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: from initial evaluation up to gastrointestinal endoscopy. Med Clin North Am. 2008 May;92(3):491-509, xi.

- Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, et al. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 2;382(14):1299-1308.

- Cooper GS, Chak A, Connors AF Jr, et al. The effectiveness of early endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: A community-based analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:462–74.

- Cooper GS, Chak A, Way LE, et al. Early endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Associations with recurrent bleeding, surgery, and length of hospital stay. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:145–52.

- Cooper GS, Kou TD, Wong RC. Use and impact of early endoscopy in elderly patients with peptic ulcer hemorrhage: A population-based analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:229–35.

- Wysocki JD, Srivastav S, Winstead NS. A nationwide analysis of risk factors for mortality and time to endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:30–6

- Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, et al. Early or delayed endoscopy for patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. A prospective randomized study. J Clin 1996;22:267–71.

- Bjorkman DJ, Zaman A, Fennerty MB, et al. Urgent vs. elective endoscopy for acute non-variceal upper-GI bleeding: An effectiveness study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:1–8.

- Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, et al. Endoscopy-based triage significantly reduces hospitalization rates and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:755–61.

- Laursen SB, Leontiadis GI, Stanley AJ, et al. Relationship between timing of endoscopy and mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: A nationwide cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:936–44 e3.

- Bai Z, Wang R, Cheng G, et al. Outcomes of early versus delayed endoscopy in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec 1;33(1S Suppl 1):e868-e876.

- Garg SK, Anugwom C, Campbell J, et al. Early esophagogastroduodenoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a nationwide study. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E376-E386.

- Siau K, Hodson J, Ingram R, et al. Time to endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results from a prospective multicentre trainee-led audit. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:199-209.

- Jeong N, Kim KS, Jung YS, et al. Delayed endoscopy is associated with increased mortality in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:277-280.

- Ahn DW, Park YS, Lee SH, et al. Clinical outcome of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding after hours: the role of urgent endoscopy. Korean J Intern Med. 2016; 31: 470-478.

- Kumar NL, Cohen AJ, Nayor J, et al. Timing of upper endoscopy influences outcomes in patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:945-952.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017 Jan;65(1):310-335.

- de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, et al; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII – Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022 Apr;76(4):959-974.

- Balderas V, Bhore R, Lara LF, et al. The hematocrit level in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: safety of endoscopy and outcomes. Am J Med. 2011 Oct;124(10):970-6.

- Sverden E, Mattsson F, Lindstrom D, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization compared with surgery for uncontrolled peptic ulcer bleeding: A population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2019;269:304–9.

- Loffroy R, Rao P, Ota S, et al. Embolization of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage resistant to endoscopic treatment: results and predictors of recurrent bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010 Dec;33(6):1088-100.

- Mirsadraee S, Tirukonda P, Nicholson A, et al. Embolization for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal tract haemorrhage: a systematic review. Clin Radiol. 2011 Jun;66(6):500-9.

- Ripoll C, Bañares R, Beceiro I, et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004 May;15(5):447-50.

- Duvnjak S, Andersen PE. The effect of transcatheter arterial embolisation for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dan Med Bull. 2010 Mar;57(3):A4138.

- Bridwell RE, Long B, Ramzy M, Gottlieb M. Balloon Tamponade for the Management of Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2022 Apr;62(4):545-558.

- D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995 Jul;22(1):332-54.

- Hunt PS, Korman MG, Hansky J, Parkin WG. An 8-year prospective experience with balloon tamponade in emergency control of bleeding esophageal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27(5):413-416.

- Nadler J, Stankovic N, Uber A, et al. Outcomes in variceal hemorrhage following the use of a balloon tamponade device. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(10):1500-1502.

- Jayakumar S, Odulaja A, Patel S, et al. Surviving Sengstaken. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(7):1142-1146.

- Ni J Bin, Xiang XX, Wu W, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients treated with a balloon tamponade for variceal hemorrhage without response to high doses of vasoactive drugs: A real-world multicenter retrospective study. J Dig Dis. 2021;22(5):236-245.

- Chaudhuri D, Bishay K, Tandon P, et al. Prophylactic endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients with upper gastrointestinal bleed: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JGH Open. 2019 May 24;4(1):22-28.

- Almashhrawi AA, Rahman R, Jersak ST, et al. Prophylactic tracheal intubation for upper GI bleeding: A meta-analysis. World J Metaanal. 2015 Feb 26;3(1):4-10.

- Perisetti A, Kopel J, Shredi A, et al. Prophylactic pre-esophagogastroduodenoscopy tracheal intubation in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019 Jan;32(1):22-25.

- Alshamsi F, Jaeschke R, Baw B, Alhazzani W. Prophylactic Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Undergoing Endoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2017 Sep-Dec;5(3):201-209.

- Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. 2000 Oct 14;356(9238):1318-21.

- Pognonec C, Dirhoussi Z, Cury N, et al. External validation of Glasgow-Blatchford, modified Glasgow-Blatchford and CANUKA scores to identify low-risk patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in emergency departments: a retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2023 Jun;40(6):451-457.

- Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996 Mar;38(3):316-21.

- Cheng HC, Wu CT, Chang WL, et al Double oral esomeprazole after a 3-day intravenous esomeprazole infusion reduces recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding in high-risk patients: a randomised controlled study. Gut. 2014 Dec;63(12):1864-72.

- Pang SH, Ching JY, Lau JY, et al. Comparing the Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall score in predicting the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Jun;71(7):1134-40.

- Chen IC, Hung MS, Chiu TF, Chen JC, Hsiao CT. Risk scoring systems to predict need for clinical intervention for patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Am J Emerg Med. 2007 Sep;25(7):774-9.

- Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, et al; International Gastrointestinal Bleeding Consortium. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017 Jan 4;356:i6432.

- Laursen SB, Oakland K, Laine L, et al. ABC score: a new risk score that accurately predicts mortality in acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: an international multicentre study. 2021 Apr;70(4):707-716.

- Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, et al. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec;74(6):1215-24.

- Abougergi MS, Charpentier JP, Bethea E, et al. A Prospective, Multicenter Study of the AIMS65 Score Compared With the Glasgow-Blatchford Score in Predicting Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul;50(6):464-9.

- Kim MS, Choi J, Shin WC. AIMS65 scoring system is comparable to Glasgow-Blatchford score or Rockall score for prediction of clinical outcomes for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul 26;19(1):136.

- Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jun;83(6):1151-60.

- Oakland K, Kahan BC, Guizzetti L, et al. Development, Validation, and Comparative Assessment of an International Scoring System to Determine Risk of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;17(6):1121-1129.e2.

- Kherad O, Restellini S, Almadi M, et al. Comparative Evaluation of the ABC Score to Other Risk Stratification Scales in Managing High-risk Patients Presenting With Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023 May-Jun 01;57(5):479-485.

- Goff S, Friedman E, Toro B, et al. Utility of the CANUKA Scoring System in the Risk Assessment of Upper GI Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul 1;57(6):595-600.

- Ramaekers R, Mukarram M, Smith CA, Thiruganasambandamoorthy V. The Predictive Value of Preendoscopic Risk Scores to Predict Adverse Outcomes in Emergency Department Patients With Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review. Acad Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;23(11):1218-1227.

- Quach DT, Dao NH, Dinh MC, et al. The Performance of a Modified Glasgow Blatchford Score in Predicting Clinical Interventions in Patients with Acute Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Vietnamese Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Gut Liver. 2016 May 23;10(3):375-81.

- Shahrami A, Ahmadi S, Safari S. Full and Modified Glasgow-Blatchford Bleeding Score in Predicting the Outcome of Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding; a Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2018;6(1):e31.

- Boustany A, Alali AA, Almadi M, et al. Pre-Endoscopic Scores Predicting Low-Risk Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug 9;12(16):5194.