Authors: Erik Sherman, MD (EM Resident Physician, Mount Sinai Morningside/West) and Chen He, MD (EM Assistant Professor, Program Director, Mount Sinai Morningside/West) // Reviewed by: Edward Lew, MD (@elewMD); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case 1:

A 16-year-old female presents after accidentally closing a car door on her right thumb. The nail and surrounding soft tissues appear intact, but there is a purple discoloration beneath approximately 75% of the nail (Picture 1). She has full active range of motion of her thumb at the IP and MCP joints, with significant tenderness over the distal phalanx. She reports ongoing, throbbing pain.

Questions: What is on your differential diagnosis for this patient? What methods can you use to treat this condition acutely? Do you need to remove the nail?

Case 2:

A 35-year-old male presents with a crush injury to his left 5th digit after an industrial accident (Picture 2). A portion of his fingernail has been avulsed, and remains only partially attached to the nailbed. He also has a laceration to the nailbed itself, which cannot be completely visualized.

Questions: What is on your differential diagnosis for this patient? How should you evaluate the extent of nailbed trauma, and what are the evidence-based recommendations for management and repair? What other significant associated injuries are important to consider? When do patients require emergent orthopedic/hand surgery consultation, and what are the appropriate follow-up recommendations?

Background:

A stable and functional fingertip and nail are critical to the sensation, strength, fine motor function, durability, and cosmetic appearance of the hand.1-3 Many activities place the fingertips at risk because they are often the first part of the hand exposed to various obstacles, including doors and machinery. Not surprisingly, hand and fingertip trauma account for approximately 4.8 million emergency department visits annually.3 These injuries range in severity, but include subungual hematomas, nailbed lacerations or avulsions, phalanx fractures or dislocations, and complete or partial fingertip amputations. With a foundational understanding of the relevant anatomy and potential red flag findings, many of these injuries can be managed definitively in the emergency department without emergent specialist consultation. However, mismanagement or inadequate repair can easily lead to chronic deformity and disability.2-5

Anatomy:

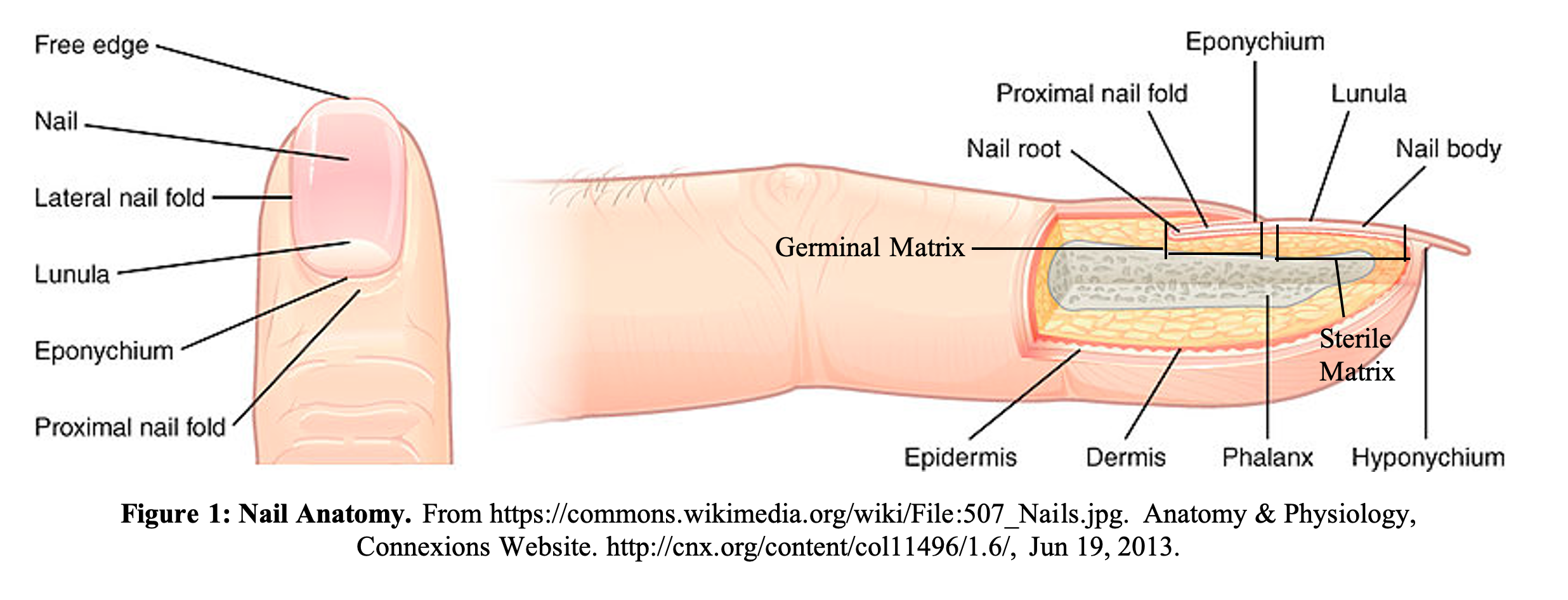

A clear understanding of the anatomy of the fingernail and distal fingertip is crucial for evaluating and managing these types of injuries. The nail, nail folds, nail bed, and surrounding soft tissue make up the perionychium (see Figure 1). The proximal nail fold contains the germinal matrix, where keratinized cells continuously replicate and generate the majority of nail growth. The germinal matrix extends from within the nail fold distally to the lunula, where it transitions to the sterile matrix. The sterile matrix attaches to the underside of the nail plate and provides stability and a small amount of additional nail growth. The hyponychium begins at the junction between the sterile matrix and the distal fingertip skin, where the nail becomes non-adherent. Any injuries involving the nail folds or proximal nail plate are especially concerning, as they can potentially jeopardize future nail growth and regeneration if not repaired adequately.1,6,7 The Van Beek Criteria offers a method to stratify nailbed injuries based on the precise location and extent of trauma (shown below).8

Sterile Matrix Injury

- SI: Small subungual hematoma (<25% nailbed surface)

- SII: Sterile matrix laceration, large subungual hematoma (>50% nailbed surface)

- SIII: Sterile matrix laceration with tuft fracture

- SIV: Sterile matrix fragmentation

- SV: Sterile matrix avulsion

Germinal Matrix Injury

- GI: Small subungual hematoma proximal nail (<25% nailbed surface)

- GII: Germinal matrix laceration, large subungual hematoma (>50% nailbed surface)

- GIII: Germinal matrix laceration and fracture of distal phalanx

- GIV: Germinal matrix fragmentation

- GV: Germinal matrix avulsion

Initial Evaluation:

Patients with nailbed injuries will generally present acutely with pain, swelling, bleeding, deformity, and inability to fully use the affected digit. Important historical elements include hand dominance, involved digit, mechanism of injury, occupation, and previous medical and surgical conditions. These factors may help guide expected pathology, associated infection risk or injury to deeper structures, as well as the need for emergent consultation or outpatient follow up.

A thorough physical examination must be performed to allow for full visualization of the injury.1,3,9 Individually examine the extensor digitorum, flexor digitorum profundus, and the flexor digitorum superficialis of the affected digit. Weak, limited, or significantly painful movement may suggest injury to an associated tendon. Assess pain and light touch sensation in the median, ulnar, and radial nerve distributions. Also assess the digital nerves by static two-point discrimination (normal <6mm). It is especially important to assess sensation at the ulnar side of the distal thumb and the radial side of the 2nd digit volar pad, as these areas are vital to pinch sensation.1,3 It is important to attempt to assess sensation prior to any local or regional anesthetic is given. Assess proximal vascular sufficiency by palpating the radial and ulnar pulses. Distal circulatory function can be assessed using capillary refill or with a doppler probe to detect decreased flow in the digital arteries.10

Any visibly contaminated wound should be thoroughly cleaned and irrigated and tetanus prophylaxis should be administered as indicated. If the patient presents with any portion of an avulsed nail, it should also be carefully examined for retained germinal or sterile matrix tissue, cleaned, and kept for possible use in repair.1,3

Greater than 50% of patients who present to the ED with nailbed injuries will also have an underlying distal phalanx fracture.11,12 As such, it is recommended that all patients with nailbed injuries receive an X-ray to evaluate for fracture or dislocation. Simple, nondisplaced distal phalanx fractures (“Tuft fractures”) are generally managed supportively with repair of any overlying nailbed injury and application of an external aluminum finger splint to prevent movement at the DIP joint and provide protection from further injury. However, with fractures of the middle and proximal part of the distal phalanx, or with those that are significantly displaced, more advanced reconstructive techniques including operative fixation are often indicated.11-13 Comminuted fractures of the distal phalanx are common, given these injuries are commonly secondary to crush mechanisms (Picture 2). In these cases, repair of the of the nailbed injury allows for approximation of any small bony fragments.9

Digital Nerve Block:

In order to adequately perform these steps of visualization and examination, many patients will first require some intervention to provide hemostasis and local anesthesia. A tourniquet can be applied briefly to the affected digit to help create a bloodless field. If a tourniquet or Penrose drain is unavailable, the finger from a nitrile exam glove can be cut off and rolled onto the finger like a ring.

Local anesthesia is most often achieved using a digital nerve block. The most common technique requires two separate injections at the base of the digit and targets a ring of anesthetic at the two dorsal and two palmar branches of the digital nerve.1,14 After the skin is prepped, the patient’s hand is placed on a flat surface, with the palmar surface facing down and digits spread apart. A 27-gauge needle is inserted perpendicularly in the webspace near the base of the proximal phalanx, and advanced toward the palmar surface. Just before the needle begins to tent the skin on the palmar surface, 1mL of anesthetic is injected to block the palmar branch. While slowly withdrawing the needle, another 1mL of anesthetic is injected to block the dorsal branch. The procedure is then repeated on the other side of the digit. Alternate techniques allow for a single injection by targeting the flexor tendon sheath, though this approach may not fully anesthetize the distal fingertip. This technique can also be used in conjunction with the “ring block” method described above if adequate anesthesia cannot be achieved.1,17

Traditionally, the use of lidocaine with epinephrine has been controversial, due to fear of digital ischemia and necrosis. However, in patients with normal baseline peripheral circulation, studies have not demonstrated any significant difference in outcomes after digital blocks performed with lidocaine with epinephrine.15,16

Subungual Hematoma Treatment:

A subungual hematoma is an accumulation of blood under an intact nail plate, often the result of a direct crush injury to the fingertip, similar to Case 1 above. This injury often requires decompression for pain relief, typically through trephination or complete removal of the nail plate. This is often performed within 24-48 hours of the initial injury. 1,12The amount of the nail that is involved with the hematoma has traditionally dictated whether intervention was necessary—typically if 50% or more of the nail is involved, trephination is indicated.1,3,12,18 The most common method of nail plate trephination utilizes electrocautery to quickly and painlessly burn a hole through the nail plate to express the underlying hematoma. Alternatively, a punch biopsy, scalpel or 18-gauge needle can be used to carefully bore a hole through the nail.1,3,18 With any method, it is critical to take care to avoid further injuring the underlying nailbed. After trephination, pain relief is generally immediate, and patients should be instructed to soak the affected finger in warm, soapy water 2-3 times daily for one week.1

Evidence regarding the appropriate management of subungual hematomas larger than 50% of the nailbed, or those associated with underlying distal phalanx fractures remains somewhat controversial. Classically in these cases, removal of the nail and direct examination of the nail bed has been recommended.12,13 However, if the nail fold edges and underlying germinal matrix tissue are intact, and there is no displaced fracture, then trephination has shown similar cosmetic outcomes and complication rates, regardless of the size of the hematoma.12,18 As an adjunct, ultrasound can be used to evaluate extent of soft tissue disruption of the nailbed, and is also extremely sensitive and specific at identifying underlying distal phalanx fractures.19

Nailbed Laceration and Nail Avulsion:

Patients presenting with more severe injuries, including large nailbed lacerations, avulsions or amputations, will generally require alternative methods of evaluation and repair. Due to potentially sensitive functional and cosmetic issues, fingertip amputations, phalanx fractures that are displaced or complicated, or injuries with significant damage to the nail fold warrant emergent consultation with a hand surgeon to consider immediate vs delayed repair with advanced surgical techniques, including various flap procedures, grafting or nail matrix transfer.3,5,12,13,20

As mentioned above, removal of all or part of the nail is generally indicated when there is significant damage to the nail plate, disruption of the nail folds, or with a displaced distal phalanx fracture.12 After a digital block is performed, the nail can be removed by first bluntly dissecting the nail plate from the nail bed using Iris scissors, and then providing gentle outward traction with a pair of clamps.1,3,7,13 Gripping the nail as proximally as possible minimizes the risk of breaking the nail, or causing additional nailbed trauma as it is removed. Classic repair of the nail bed consists of approximation of the lacerated edges with 6.0 chromic or other small, absorbable suture.1,12 Alternatively, medical adhesives such as Dermabond can also be used to effectively repair these injuries. Though sample sizes are frequently small, research has shown that adhesives achieve similar cosmetic outcomes and complication rates compared to repair with sutures.12,21 If attempting primary closure with an adhesive, it is critical that the injury be well-exposed and bloodless to ensure quick and complete drying and adequate hemostasis.

Another controversial element of wound management in nailbed injuries involves the replacement or splinting of the nail fold after repair. Replacement of a native or prosthetic nail theoretically serves to protect and splint any underlying injuries, keeps the nail folds open to maintain normal shape and anatomy for future nail growth, and may possibly replace any portion of the proximal germinal matrix attached to the nail. However, replacement may also be associated with higher rates of infection, pain and delayed healing.12,13 When the nail is unavailable, or is significantly damaged, a common solution is to use a silicone nail prosthesis, or to craft an artificial nail using the outer foil of a chromic suture package.12,22 The foil is cut to a size and shape similar to the native nail, with care taken to avoid and sharp edges, and then placed within the proximal nail fold. Various strategies exist to suture or secure the nail in place, though there is no clear evidence that any specific technique is superior.3,5,6,12

The NINJA (Nailbed INJury Analysis) Trial is an ongoing, randomized multicenter study looking at short-term and long-term outcome of nail plate replacement after nailbed repair in children, and may provide more insight into management strategy.23 When repairing these injuries, great care should be taken not to cause any additional local tissue trauma, or incur accidental needle sticks—especially when attempting to create a hole in a native nail to suture it in place.

Distal phalanx fractures with overlying nailbed injuries are technically “open” fractures, but antibiotic prophylaxis is not generally indicated. Studies have shown no statistically significant difference in the rate of superficial infection or osteomyelitis in patients who receive antibiotics.12, 24, 25 In order to limit infection risk, the focus of treatment should be on prompt irrigation and debridement.

Follow-up/Disposition:

Patients with fingertip amputations, phalanx fractures that are displaced or complicated, or have significant damage to the nail fold should have emergent consultation with a hand surgeon. Otherwise, any patient requiring nailbed repair in the ED can generally follow up with a hand surgeon on an outpatient basis to monitor for normal wound healing or evaluation for additional repair as indicated. Patients with small subungual hematomas without an associated distal phalanx fracture do not require specialist follow up.1,3,12

Clinical Case 1 Resolution:

A thorough physical exam reveals the patient’s sensation, strength/range of motion (at the DIP, PIP and MCP joints) and capillary refill are fully intact. An X-ray of the affected digit demonstrates no underlying acute traumatic fracture or dislocation. The patient is diagnosed with an uncomplicated subungual hematoma, and is given 600mg ibuprofen for analgesia. Trephination of the nailbed is performed using electrocautery, which results in immediate relief of pain. The patient is discharged home with instructions for warm water soaks for 1 week.

Clinical Case 2 Resolution:

To provide analgesia and allow for a complete physical exam, a digital block is performed using lidocaine in the ring-block technique. Though sensation is intact, you note that the patient is unable to fully range at the DIP due to pain. Capillary refill is normal. An X-ray of the affected digit confirms a mildly displaced distal phalanx fracture. Orthopedic surgery/hand surgery is consulted for this complex nailbed laceration. In order to fully expose and repair the nailbed, the entire nail is removed. A slowly oozing 0.5 cm laceration to the nail bed is identified, cleaned, debrided and repaired with 6-0 chromic sutures. Several 5-0 nylon sutures are used to repair a laceration over the DIP joint. The native nail is discarded, and a chromic suture foil is molded to create a prosthetic nail and inserted within the nail fold. The digit is placed in an aluminum splint, and the patient is given follow up with hand surgery in 1 week.

Clinical Pearls:

- For all nailbed injuries, perform a thorough exam to assess neurovascular status and identify involved tissue, and obtain an X-ray to rule out underlying phalanx fractures.

- Consider trephination alone instead of nail removal – even for large subungual hematomas – so long as the nail fold edges are intact and there is no underlying displaced phalanx fracture.

- Lacerations to the nailbed can be repaired effectively with similar outcomes using either absorbable sutures or tissue adhesive.

- Replacement of the nail or use of another material to splint the nail fold after repair remains controversial, and ongoing studies hope to provide a clearer management plan.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is not generally indicated in patients with nailbed trauma with simple open distal phalanx fractures (of note: controversial).

References:

- Tintinalli, JE, Stapczynski, JS, Ma, OJ, Yealy, DM, Meckler, GD, & Cline, D (2016). Arm, Forearm and Hand Lacerations. Tintinalli’s emergency medicine: A comprehensive study guide (Ninth edition.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Yeo C.J., Sebastin S.J., Chong A.K. Fingertip injuries. Singap. Med. J. 2010;51(1):78–86. Epub 2010/03/05.

- Hawken JB, Giladi AM. Primary Management of Nail Bed and Fingertip Injuries in the Emergency Department. Hand Clin. 2021 Feb;37(1):1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2020.09.001.

- Sorock GS, Lombardi DA, Hauser RB, et al. Acute traumatic occupational hand injuries: type, location and severity. J Occup Environ Med 2002; 44:345-51.

- Sindhu K, DeFroda SF, Harris AP, et al. Management of partial fingertip amputation in adults: operative and non operative treatment. Injury 2017;48(12): 2643–9.

- Lee DH, Mignemi ME, Crosby SN. Fingertip injuries: an update on management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013 Dec;21(12):756-66. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-12-756. PMID: 24292932.

- Brown RE. Acute nail bed injuries. Hand Clin. 2002 Nov;18(4):561-75. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(02)00075-6. PMID: 12516973.

- Van Beek AL, Kassan MA, Adson MH, Dale V. Management of acute fingernail injuries. Hand Clin. 1990 Feb;6(1):23-35; discussion 37-8. PMID: 2179235.

- Abramson T, Miller S. Nail Bed Injuries. In: Mattu A and Swadron S, ed. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recOwas4iU6IZFWnJ/Nail-Bed-Injuries. Updated March 1, 2021. Accessed May 9, 2021.

- Levy BA, Zlowodzki MP, Graves M, et al. Screening for extremity arterial injury with the arterial pressure index. Am J Emerg Med 23: 689, 2005.

- George A, Alexander R, Manju C. Management of Nail Bed Injuries Associated with Fingertip Injuries. Indian J Orthop. 2017;51(6):709-713. doi:10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_231_16

- Venkatesh A, Khajuria A, Greig A. Management of Pediatric Distal Fingertip Injuries: A Systematic Literature Review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020 Jan 20;8(1):e2595. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002595. PMID: 32095403; PMCID: PMC7015615.

- Tos P, Titolo P, Chirila NL, Catalano F, Artiaco S. Surgical treatment of acute fingernail injuries. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012 Jun;13(2):57-62. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0161-z. Epub 2011 Oct 8. PMID: 21984203; PMCID: PMC3349021.

- Napier A, Howell DM, Taylor A. Digital Nerve Block. 2021 Jan 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 30252367.

- Prabhakar H, Rath S, Kalaivani M, Bhanderi N. Adrenaline with lidocaine for digital nerve blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 19;3

- Ilicki J. Safety of Epinephrine in Digital Nerve Blocks: A Literature Review. J Emerg Med. 2015 Nov;49(5):799-809. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.05.038. Epub 2015 Aug 4. PMID: 26254284.

- Okur OM, Şener A, Kavakli HŞ, et al. Two injection digital block versus single subcutaneous palmar injection block for finger lacerations. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 43: 863, 2017.

- Roser SE, Gellman H. Comparison of nail bed repair versus nail trephination for subungual hematomas in children. J Hand Surg Am 1999;24(6):1166–70.

- Prats, M. Ultrasound for Nail Bed Injury. Ultrasound G.E.L. Podcast Blog.Published on January 16, 2017. https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/11

- Martin-Playa P, Foo A. Approach to Fingertip Injuries. Clin Plast Surg. 2019 Jul;46(3):275-283. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2019.02.001. Epub 2019 Apr 16. PMID: 31103072.

- Edwards S, Parkinson L. Is Fixing Pediatric Nail Bed Injuries With Medical Adhesives as Effective as Suturing: A Review of the Literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Jan;35(1):75-77. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000994. PMID: 27977531.

- Weinand C, Demir E, Lefering R, Juon B, Voegelin E. A comparison of complications in 400 patients after native nail versus silicone nail splints for fingernail splinting after injuries. World J Surg. 2014 Oct;38(10):2574-9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2583-2. PMID: 24777661.

- Jain A, Jones A, Gardiner MD, et al. NINJA trial: should the nail plate be replaced or discarded after nail bed repair in children? Protocol for a multicentre randomised control trial BMJ Open 2019;9:e031552. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031552

- Altergott, C, Garcia, FJ, Nager, AL. MD Pediatric Fingertip Injuries, Pediatric Emergency Care: March 2008 – Volume 24 – Issue 3 – p 148-152 doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f5d

- Metcalfe D, Aquilina AL, Hedley HM. Prophylactic antibiotics in open distal phalanx fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016 May;41(4):423-30. doi: 10.1177/1753193415601055. Epub 2015 Sep 1. PMID: 26329883.

2 thoughts on “Evidence-based Approach to Nailbed Injuries: ED Presentations, Evaluation, and Management”

Pingback: They Catch on Fire – Electrocautery Trephination with Acrylic Nails – JournalFeed

Pingback: April 2023 Asynchronous – MSK/Ortho | Harbor-UCLA DEM Education