Originally published at CoreEM.net, dedicated to bringing Emergency Providers all things core content Emergency Medicine available to anyone, anywhere, anytime. Reposted with permission.

Follow Dr. Swaminathan and CORE EM on twitter at @EMSwami and @Core_EM

Written by Darien Sutton-Ramsey, MD and Edited by Anand Swaminathan, MD

Definition: Any trauma associated with facial, orbital, nasal or jaw bones. Also known as maxillofacial trauma

Mechanism + Epidemiology

- Most commonly due to blunt trauma (violence), motor vehicle accidents, and athletic injuries. (Tintinalli 2011)

- Majority of facial trauma in patients aged 35-40

- Mostly male

- Significantly associated with traumatic brain injury, C-Spine injuries, and airway compromise (Sethi 2014)

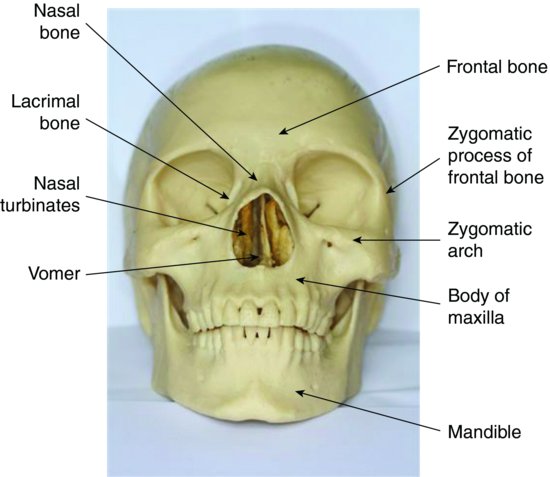

Skull Anatomy (pocketdentistry.com)

Anatomy

There are 5 important facial bony areas to evaluate in the setting of an acute facial fracture

- Frontal Bone Fracture

- Orbital Bone Fractures

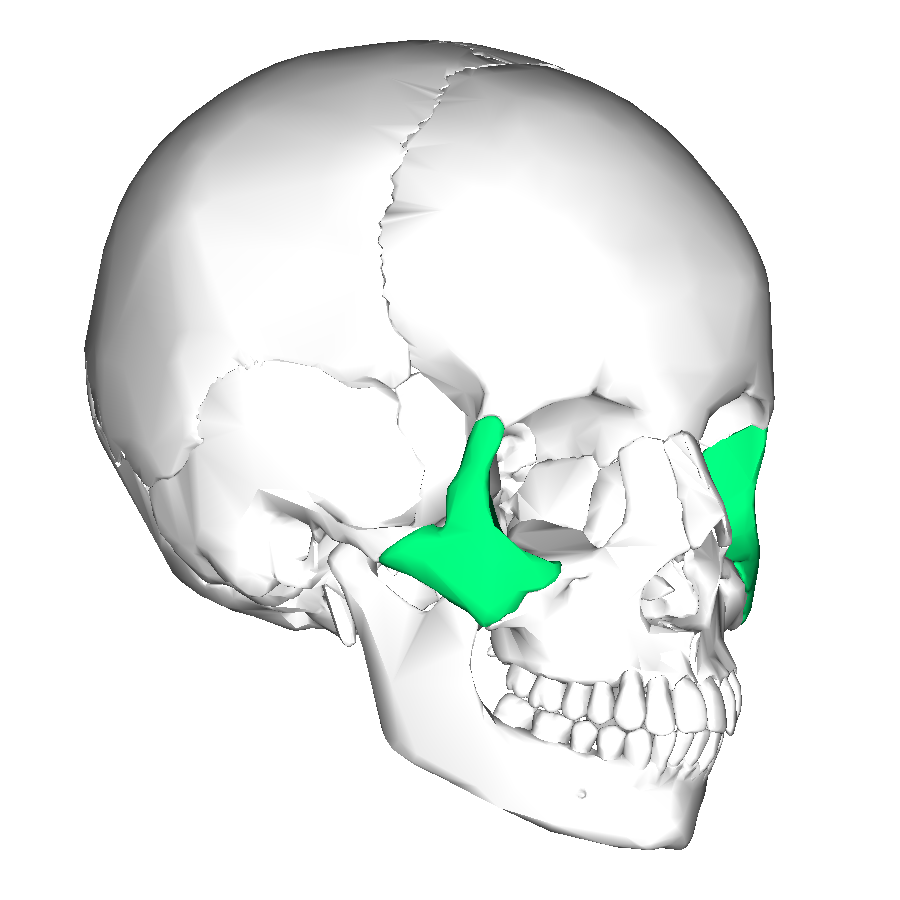

- Zygoma Fractures

- Midface (Le Fort) Fractures

- Mandibular Fractures

Specific Fractures

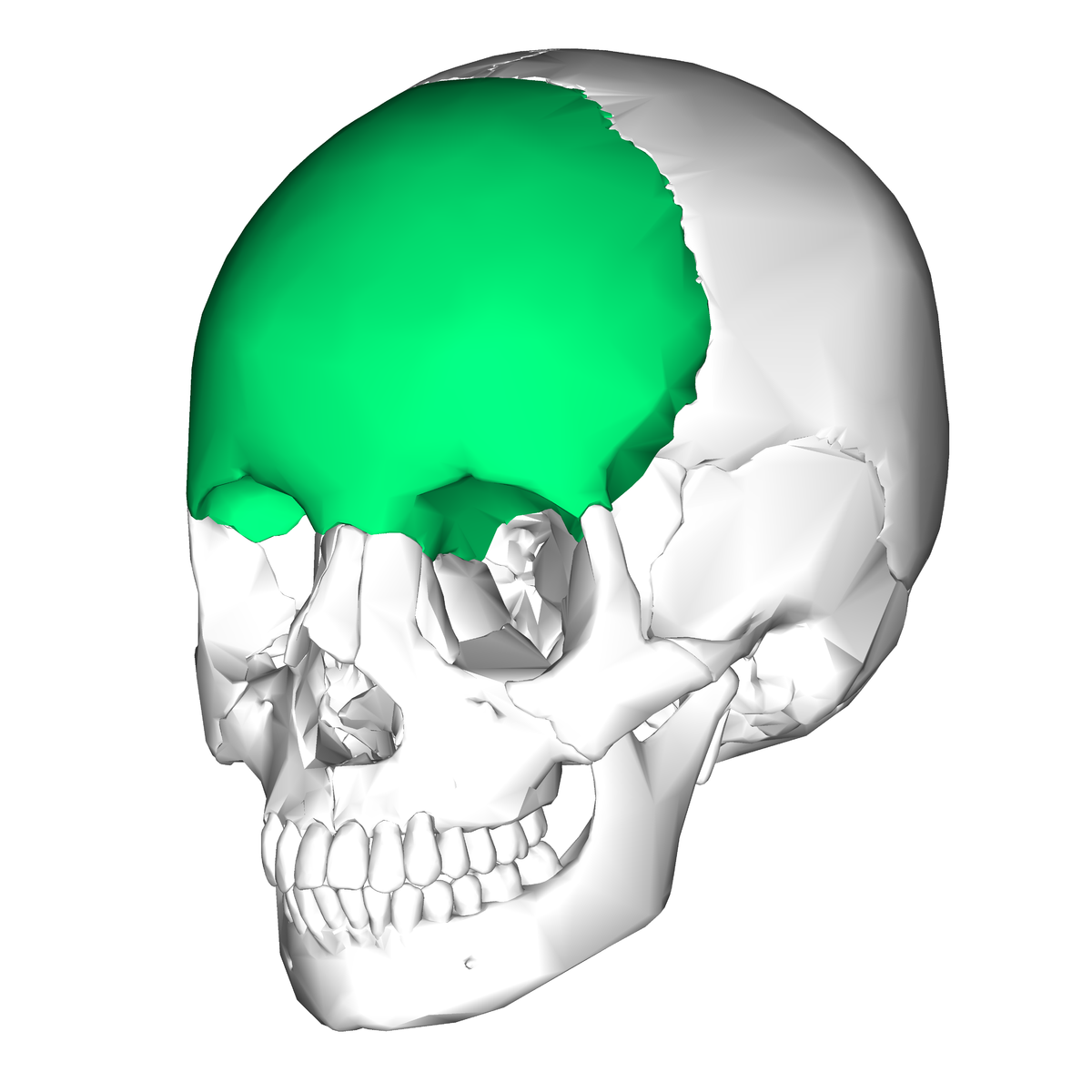

Frontal Bone (en.wikipedia.org)

Frontal Bone Fractures

- These fractures require significant force, as this is the most dense bone in the face

- Look for concomitant craniofacial trauma and intracranial brain injury

- There is also concern for associated temporal bone fracture

- Look for hearing and facial nerve dysfunction

- Any otorrhea or ear discharge is a CSF leak until proven otherwise and appropriate evaluation and treatment are important!

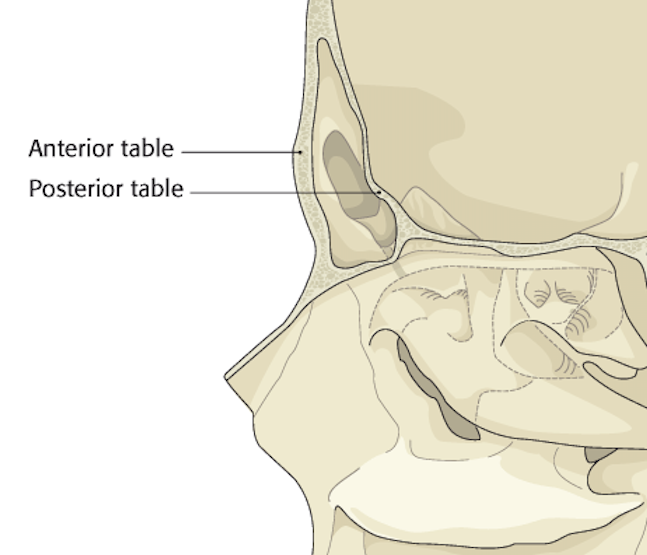

- Imaging is important to distinguish between frontal posterior and anterior table fractures

- The dura is adherent to the posterior table and disruption of this bone can lead to pneumocephalus, CSF leak and infection, therefore emergent surgical consultation is necessary. (Tintinalli 2011)

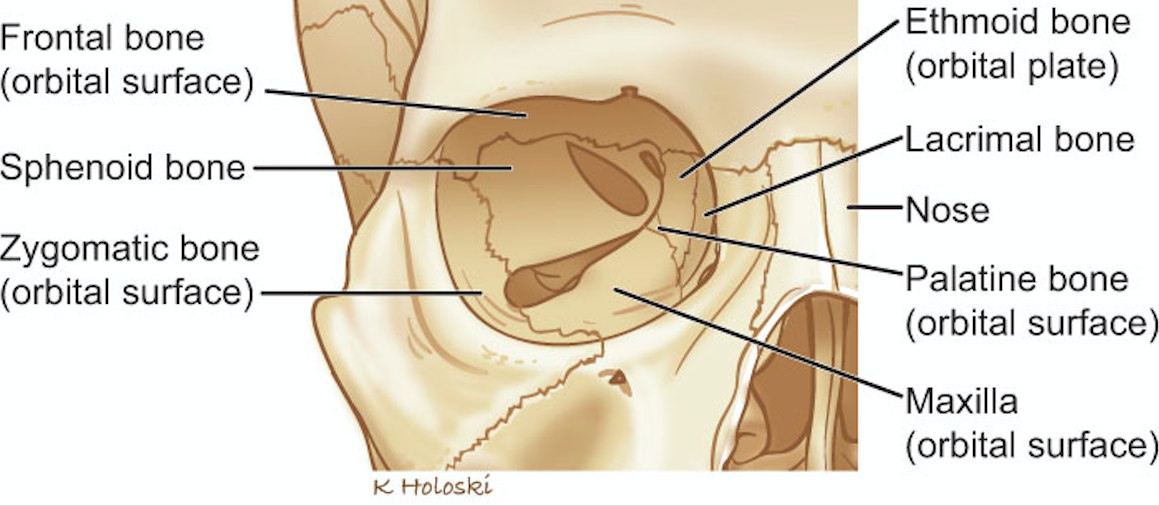

Orbital Fractures

Orbit Anatomy (headandneckcancerguide.org)

- Orbital Wall Anatomy: The bony orbit is composed of several different bones with the inferior and medial walls being the most fragile (See Photo above)

- Superior Wall: frontal bone

- Medial Wall: lamina papyracea and ethmoid bones

- Lateral Wall: zygoma and sphenoid bones

- Inferior Wall: zygoma and maxillary bone

- Note: Significant force applied to the nasal bridge can result in naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures and these are usually accompanied with intracranial injury.

- Blowout fracture

- Any fracture involving the orbital floor or medial wall

- There are closed door and trap door injuries

- The closed door is non displaced

- The trap door is usually linear and minimally displaced

- Orbital Floor Fractures

- Always evaluate for neuromuscular pathology

- These fractures are in close proximity to inferior rectus muscle. Therefore external, upward strabismus creates concern for inferior rectus entrapment.

- The maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve escapes through the inferior orbital groove

- Numbness of the middle face is a clinical sign of orbital floor fracture and nerve entrapment

- Orbital Medial Wall fractures

- Rare injuries. Documented in 4% of cases (Hutchison 1990)

- Can involve extraocular muscle disorders (medial rectus), leading to diplopia, and enophthalmos

- Medial rectus entrapment creates restricted and painful abduction and pseudo sixth nerve paresis.

Zygoma Bones

Zygoma Fractures

- Zygoma forms the inferior and lateral walls of the orbit and superior and lateral roof of of the maxillary sinus

- Zygomaticomaxillary fractures are considered orbital and sinus fractures (Tintinalli 2011)

- These are most frequently due to assault

- Signs to look for on exam

- Malar eminence flattening [Insert Photo: Facial Trauma Zygoma Bone 2]

- Lateral canthus tilting

- Diplopia

- Infraorbital anesthesia

- Trismus

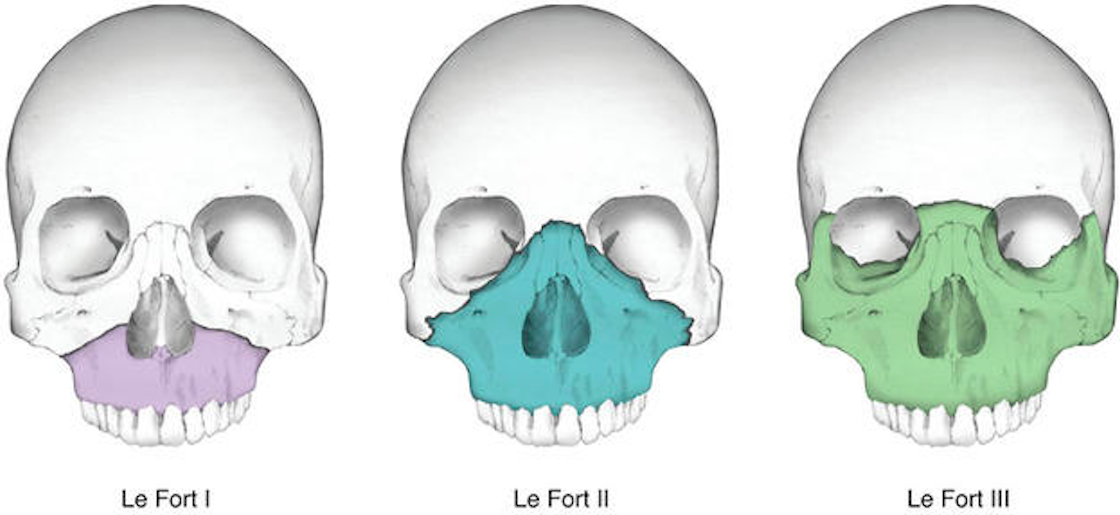

Le Fort (Midface) Fractures

Le Fort (Midface) Fractures (havemursey.com)

- Concomitant Injury Considerations

- High probability (approximately 50%) of concomitant skull, ocular and orbital fractures (Dal Canto 2008)

- Significant bleeding/swelling which need to be packed and controlled prior to evaluation, also important to check for CSF leak

- Type 1

- Floating Palate – involves the pterygoid plate, lateral nasal opening, upper alveolar plate

- Seperates body of maxilla from pterygoid and nasal septum.

- Type 2 (Medial wall and floor) Pyramidal

- Creates pyramid shape

- Inferior orbit, nasal bridge, and lacrimal bones

- There is movement of hard palate and nose but not the eyes

- Type 3 (Medial wall, posterior orbital floor, lateral wall)

- Transverse line

- Craniofacial Dislocation (involves the zygomatic arch)

- Nasofrontal and Frontomaxillary sutures and continues along the orbital floor

- Type 4: Fracture of the frontal bone with Lefort 3 fractures

Mandibular Fractures/Dislocations

- Majority of time, will see 2 or more fractures of the mandible (as opposed to a single fracture)

- Intraoral examination

- Evaluate for open fractures – any intraoral laceration with a fracture should be considered open

- Look for subungual hematomas

- Dental & Alveolar ridge fractures

- “Tongue Blade” test

- Rapid bedside assessment for fractures

- High sensitivity (>95% in some studies) for fracture (Neiner 2016)

Primary Exam

- Airway

- Airway obstruction is common in significant facial trauma and obstruction often dynamic

- Consider early securing of the airway – up to 44% with severe injury require intubation (Tintinalli 2011)

- Consider awake intubation if patient maintaining respiratory status

- In high speed mandibular injury the airway can be easily compromised due to dysfunctional swallowing mechanism. Displacement of the maxilla/mandible posteriorly can decrease airway patency (Passi 2014)

- Breathing

- Assess for stridor and associated pulmonary trauma

- Maximally pre-oxygenate patients in anticipation of intubation

- Circulation

- Maxillofacial injuries are prone to significant hemorrhage

- Control bleeding with early nasal/oral cavity packing

- Be aware facial trauma can lead to life threatening hemorrhage

- Bleeding control: Pressure packing, fracture manual reduction, if persistent: IR consultation may be needed for possible embolization.

Secondary Exam

- Inspection for facial asymmetry

- Vision, Sensation, “Bite”

- Vision testing

- Sensation: supraorbital, infraorbital, mental nerves

- Tooth alignment for possible mandibular fracture

- Ocular Exam

- Consider concomitant globe injuries

- Key findings on visual examination

- Binocular double vision: High risk extraocular muscle entrapment

- Monocular double vision: High risk lens dislocation

- Teardrop pupils: High risk globe rupture

- Hyphema

- Afferent pupillary defect

- Extraocular movements

- Fundoscopic, slit-lamp, fluorescein examination

- Pressure examination

- Nasal bridge

- Test for anosmia

- Palpation of the nasal bridge for tenderness, crepitus, movement

Nasal Trauma Exam (www2.aofoundation.org)

-

- Look for septal hematomas – Incision and drainage are necessary to prevent saddle deformity

- Midface instability

- Pack and stabilize bleeding

- Look for step offs of the upper alveolar ridge

- Grasp the superior teeth or alveolar ridge and edentulous patients and attempt to move anteriorly and posteriorly while stabilizing the head.

- Look for movement and increased bleeding

- Mouth/Maxilla/Mandible

- Ask the patient to state their name and evaluate dysphonia

- Intraoral exam assessing for superior/inferior alveolar ridge injuries

- Stensen’s Duct injuries

- Traverses over the masseter muscle into the superior alveolar ridge

- Can occur with facial injuries in this area

- Uncorrected damage to this duct may result in cutaneous fistula formation

Management

- Imaging

- CT is current gold standard

- Consider in patients with significant trauma, significant swelling or tenderness

- Antibiotics

- Often recommended in isolated orbital, sinus and frontal bone fractures

- Recommendation: first generation cephalosporins or amoxicillin/clavulanate

Frontal Bone Fracture Management

- Isolated anterior fractures

- Nasal/oral decongestants

- Close follow up with a facial surgeon

- Anterior table fractures

- Usually stable

- Can lead to cosmetic deformity if not followed

- Posterior table fractures: neurosurgery consultation

- Patients with associated intracranial, cervical spine injuries or neurovascular complications need consultation with surgery

- Antibiotics are recommended for 7-10 days

Orbital Bone Fracture Management

- Rule out orbital trauma with a complete visual acuity exam, testing pupil reflex, fundoscopic exam, slit lamp, fundoscopic exam, fluorescein, and ocular pressure testing

- Rule out retrobulbar hematoma (orbital compartment syndrome)

- Assess extraocular movements for entrapment

- Isolated orbital fractures

- treat with antibiotics and nasal decongestants

- Precautions regarding nose blowing

- Close facial surgery follow up

Zygoma/Temporal Bone Fracture Management

- Zygomatic fractures rarely need emergent surgical intervention

- Isolated temporal arch fractures can be discharged with close facial surgery follow up

- Antibiotics are up to the discretion of the clinician

- Presence of loss/change of vision requires surgical consultation

Le Fort (Midface) Fracture Management

- Requires immediate surgical consultation (and likely intervention)

- Assess the airway

- Control the bleed

- Start IV antibiotics

Mandibular Fracture CT Management

- Mandibular CT if suspicion for fracture

- CXR is needed if concerned for associated dental injury to evaluate for possible aspiration

- Surgical consultation for any fracture pattern

- Administer antibiotics if fracture is open (most commonly intraoral lacerations)

Take Home Points

- Airway complications are commonly found in facial trauma

- Awake intubation with sedation and local airway anesthesia should be considered

- Etomidate and Ketamine both provide sedation and preservation of respiratory drive

- Always consider concomitant intracranial and cervical spine injuries

- A thorough neurologic examination is necessary in all injuries

- The following injuries need emergency surgical consultation

- Mandible fractures (oral surgery)

- Frontal bone posterior table fractures (neurosurgery)

- Orbital fractures with entrapment (plastic surgery)

- Zygoma fractures with change in vision

- Midface fractures

References

Dal Canto AJ, Linberg JV. Comparison of orbital fracture repair performed within 14 days versus 15 to 29 days after trauma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(6):437-43. PMID: 19033838.

Hutchison I, Lawlor M, Skinner D. ABC of major trauma Major maxillofacial injuries. BMJ. 1990; 301(6752):595-9. PMID: 2242459

Nagori JA et al Management of maxillofacial trauma in emergency: An update of challenges and controversies. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2016; 9(2):73-80. PMID: 27162439

Neiner J et al. Tongue Blade Bite Test Predicts Mandible Fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2016 Jun;9(2):121-4. PMID: 27162567

Passi D et al. Total avulsion of mandible in maxillofacial trauma.Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4(1):115-8. PMID: 24987613

Sethi, RKV et al. Epidemiological Survey of Head and Neck Injuries and Trauma in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 151(5), 776–784. PMID: 25139950

Check out this amazing illustration from @HansonsAnatomy

1 thought on “CORE EM: Facial Fractures”

Pingback: Facial Trauma – EM Clerkship