Authors: Mark M. Ramzy, DO, EMT-P (@MRamzyDO, Emergency Medicine Resident at Drexel University, Department of Emergency Medicine) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 54-year-old female with past medical history of Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, alcohol and IV heroin abuse (both over six months ago), and depression presents to the emergency department for a cough. She reports that her cough started 3 weeks ago with clear mucus that progressed to yellow-green sputum. Over the past two days she noticed dark blood sputum with coughing. The patient also endorses an intentional weight loss of 13 pounds over the past 6 months. She denies any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, fever, chills, night sweats, or recent travel outside of the country. Pertinent positives on physical exam include the following: anxious-appearing African American female actively coughing, decreased breath sounds on the right upper chest, and dry mucous membranes. Vital signs: BP 106/69, HR 119, RR 18, SpO2 95%, and Temperature 36.7oC.

The above patient’s presentation and her overall clinical picture leave a broad differential. It is necessary for emergency physicians to identify key points in the history that raise red flags for more concerning underlying diagnoses. This post will focus on the presentation, clinical features, management, and disposition of patients with a lung abscess, on their chest x-ray. Furthermore, it will provide some pearls and pitfalls to be on the lookout for when you suspect a lung abscess.

Etiologies and Risk Factors

Lung abscesses are the result of lung parenchyma necrosis due to an underlying microbial infection. These microbes break down the body’s innate pulmonary defense mechanisms and lead to the formation of a pus-filled cavity.1,2 The most common cause of a lung abscess is aspiration pneumonia.1-3 It is vital to consider this complication in patients who pose a high risk for aspiration (Table 1). Diabetes continues to remain a known risk factor, especially with Klebsiella Pneumonia, where up to 31% of patients with lung abscess are diabetic.4,5 While alcoholism remains a known risk factor, studies suggest no difference in patients with lung abscess due to K. Pneumonia and those with a lung abscess due to other pathogens.5

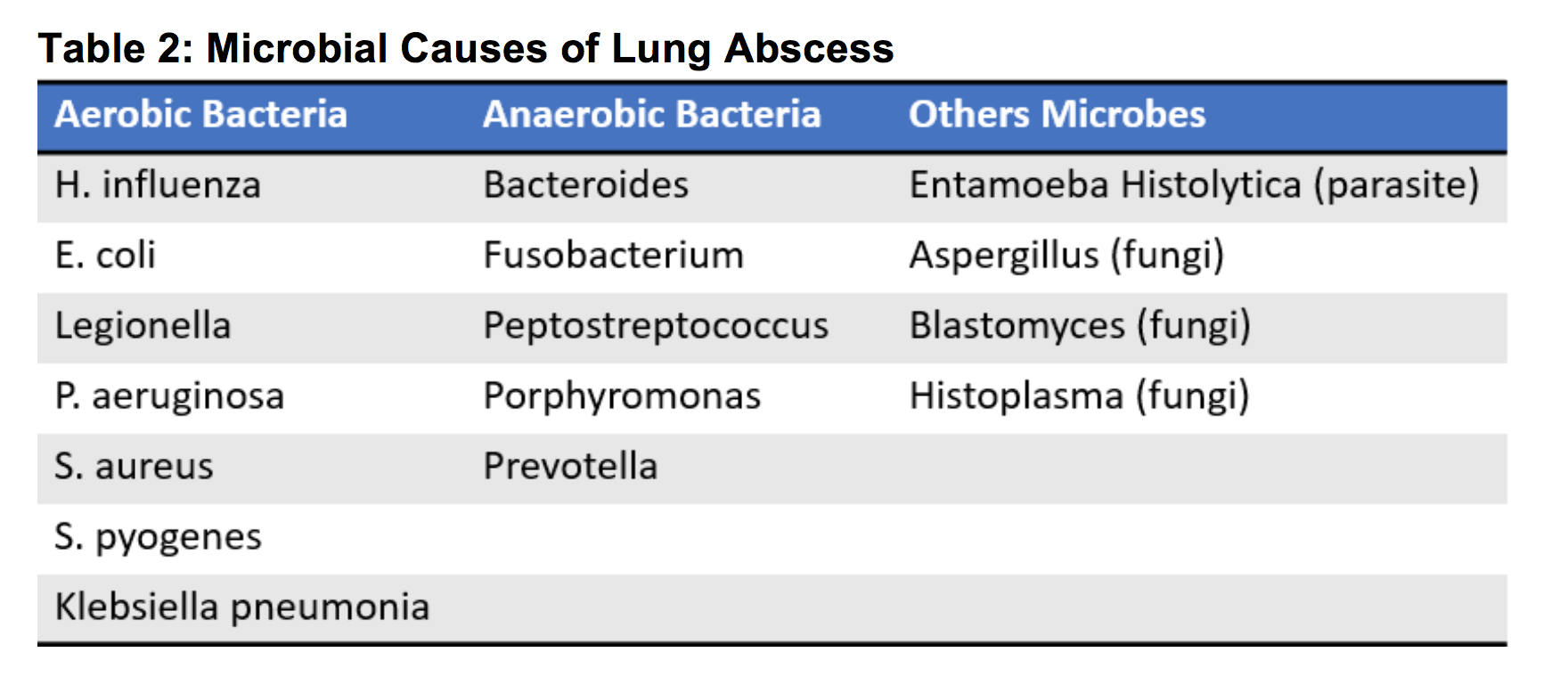

It is worth noting the types of microbes that can cause a lung abscess, as this will help guide treatment. Bacteria, parasites, and fungi all have the potential to cause a lung abscess (see Table 2).1 In terms of bacteria, anaerobes and aerobes can both cause lung abscesses, however anaerobes are more common especially in immunocompetent patients.1-5 As for the immunocompromised patient, extra caution is required when admitting these patients, as aerobic bacteria from hospital acquired infections are typically the cause of their lung abscesses.

Pearls

- Most common cause of a lung abscess is aspiration pneumonia.

- Diabetics, alcoholics, and those with poor oral hygiene are all high-risk patients for a lung abscess.

- Anaerobic bacteria are the most common causative organism of lung abscesses.

Pitfalls

- Parasites and fungi may also be the causative organisms for lung abscesses.

- Aerobic bacteria may cause lung abscesses in immunocompromised patients.

Presentation, Evaluation, and Diagnosis

Patients often present with chills, night sweats, fatigue, unexplained weight loss, and the most common symptom of fever. In fact, 80% of patients with a lung abscess have a fever, typically 38oC or higher.6 Signs of late disease include pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and a productive cough, with over half of patients reporting a putrid smell to the sputum.1,2,6 On exam, these patients may have diminished breath sounds, rales, poor dentition, and gingival disease.

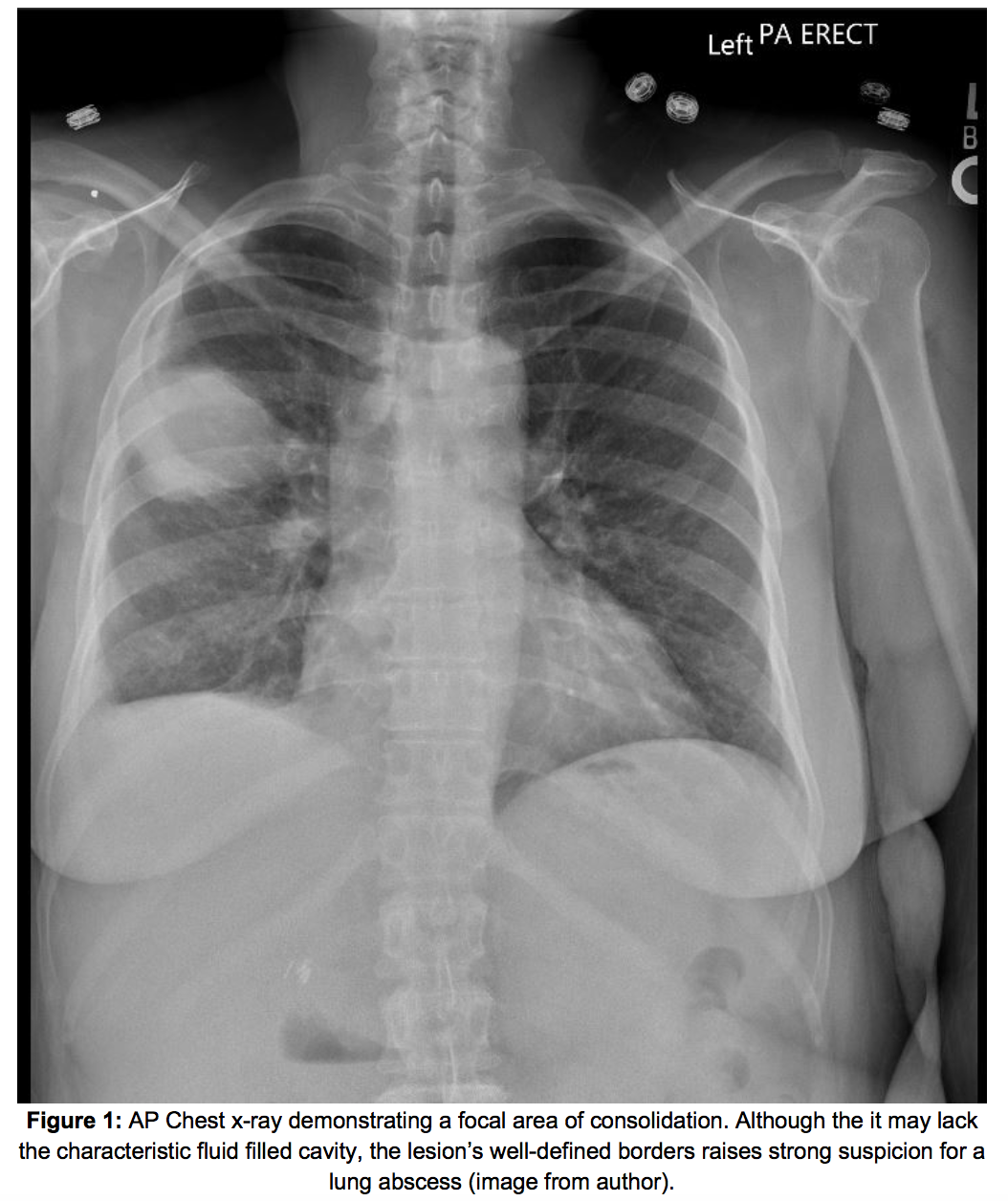

Often history and physical exam are insufficient for diagnosis of a lung abscess if used alone. A chest x-ray (CXR) can be obtained to confirm the presence of a lung abscess; however, CXR can be non-diagnostic in the early stages of the disease.2 If obtained too early, it may only show pulmonary infiltrates, otherwise a characteristic cavitating lesion can be seen. (Figure 1).1,2 If the CXR is performed upright or in the lateral decubitus position, an air-fluid level may further support the diagnosis.2

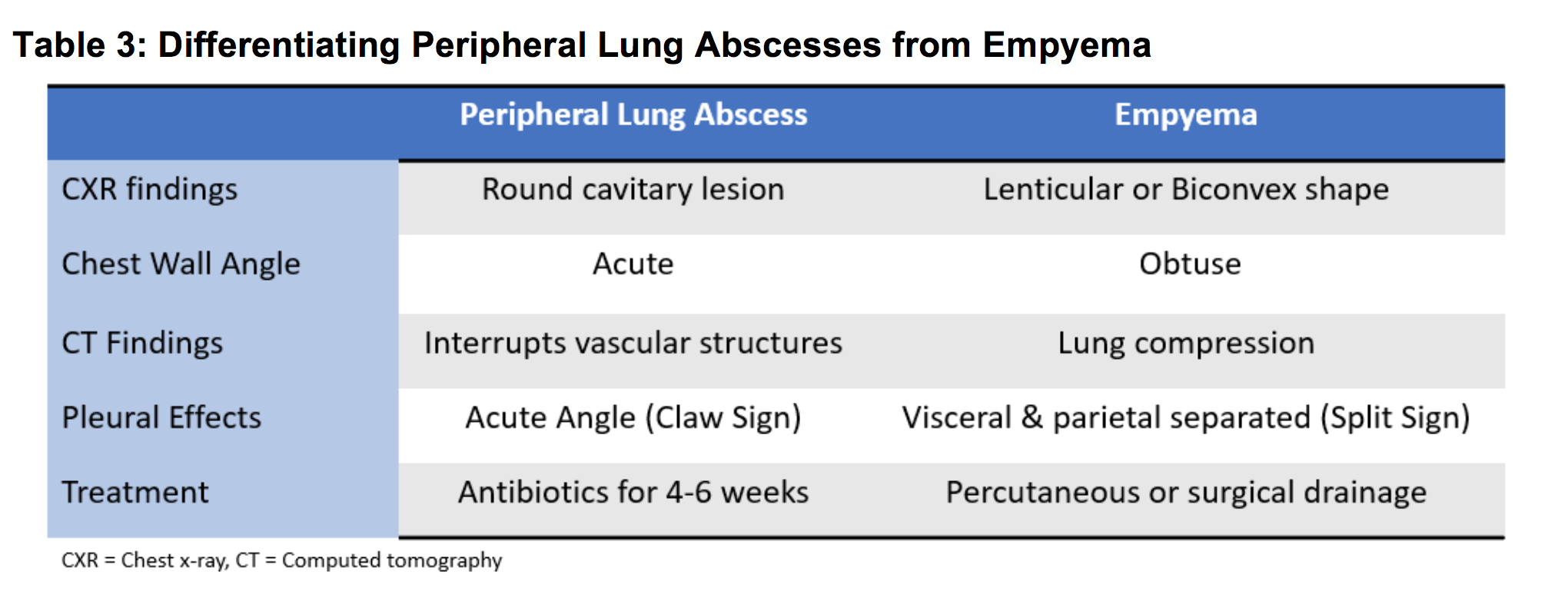

When atelectasis, pulmonary infiltrates, or poor anatomy obscures the lung on a radiograph, a Chest CT can assist in diagnosis (Figure 2) and may help evaluate the size and severity of the abscess. CT has been shown to be more sensitive than CXR in detecting small cavities within consolidation and more importantly to differentiate lung abscesses from empyema.1,8 It is imperative that a lung abscess be distinguished from an empyema, especially when a peripherally located abscess, as this changes management (See Table 3).8,9 It is not uncommon to see a coinciding pleural effusion, which may be a result of the lung abscess itself (Figure 3).9,10 The CT will also assist in ruling out other conditions such as an infected cyst, infected bullae, bronchiectasis, pneumonia and conditions associated congenital abnormalities or malignancy.

Pearls

- Foul smelling sputum in a febrile patient should prompt consideration of a lung abscess.

- History and physical exam alone are often insufficient for the diagnosis.

- If possible, obtain an upright or lateral decubitus CXR to better visualize air-fluid levels.

- CT provides the most reliable diagnostic modality.

Pitfalls

- Obtaining a CXR too early in disease course may only show pulmonary infiltrates.

- Don’t confuse empyema for a peripheral lung abscess; Chest CT can help differentiate the two.

- Other coinciding disease processes can exist such as pneumonia or a pleural effusion.

Management and Disposition

CBC may reveal a leukocytosis. Blood cultures can help identify the causative organism; however, they are rarely positive in anaerobic lung abscess. Sputum cultures should be obtained in hospitalized or septic patient to better adjust antibiotic dosing and to assist in differentiating aerobic, fungal, or bacterial pathogens.

Patients who may not be compliant with oral antibiotic therapy, lack poor outpatient follow-up, or require IV antibiotics due to sepsis, hypoxia, or any other underlying medical condition which alters their mentation should be admitted for further monitoring.

More aggressive therapies, such as lobectomy or pneumonectomy, may be indicated for 10-15% for patients who fail to improve with appropriate antibiotic therapy.1 If fevers persist for 5-7 days or are accompanied with hemoptysis, or if the cavitation is larger than 6 cm, consider surgical intervention.10,11 Other alternative therapies, such as percutaneous or bronchoscopic drainage, may be necessary if patients are poor surgical candidates.2, 9,10.

Antibiotic treatment options include the following:

- Clindamycin, 600 mg intravenously (IV) every 8 hours followed by 150-300mg orally four times a day for 4-6 weeks.

- Ampicillin-Sulbactam, 1.5 – 3.0 grams IV every 6 hours.

- Piperacillin-Tazobactam, 3.375 grams IV every 6 hours.

- Linezolid, 600 mg IV every 12 hours or Vancomycin, 15 mg/kg IV every 12 hours (if MRSA positive).1-3

Pearls:

- Obtain sputum cultures in hospitalized or septic patients to better focus antibiotic therapy.

- Clindamycin is the first line antibiotic of choice; transition from IV to PO when appropriate.

Pitfalls

- Blood cultures are rarely positive in anaerobic lung abscesses.

- Consider admission and IV antibiotics rather than discharging patients with poor outpatient follow-up or those who may be non-compliant with antibiotics.

References/Further Reading

- Desai H, Agrawal A. Pulmonary Emergencies. Medical Clinics of North America. 2012;96(6):1127-1148. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.08.007

- Witzke H, Anikin V. Other conditions of the lung (abscesses, inhaled foreign bodies, bullous lung disease, hydatid). Surgery (Oxford). 2014;32(5):261-265. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2014.02.013

- Bartlett J.G.: Anaerobic bacterial infections of the lung and pleural space. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16: pp. S248-S255

- Takayanagi N, Kagiyama N, Ishiguro T et al.: Etiology and outcome of community-acquired lung abscess. Respiration 80: 98, 2010.

- Wang JL, Kuan-Yu C, Chi-Tai F et al.: Changing bacteriology of adult community acquired lung abscess in Taiwan: Klebsiella pneumonia vs anaerobes. Clin Infect Dis 40: 915, 2005.

- Hirshberg B et al: Factors predicting mortality of patients with lung abscess. Chest. 115(3):746-50, 1999

- Lorber B., and Swenson R.M.: Bacteriology of aspiration pneumonia. A prospective study of community- and hospital-acquired cases. Ann Intern Med 1974; 81: pp. 329-331

- Stark D, Federle M, Goodman P, Podrasky A, Webb W. Differentiating lung abscess and empyema: radiography and computed tomography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1983;141(1):163-167. doi:10.2214/ajr.141.1.163

- Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M. Mandell, Douglas, And Bennett’s Principles And Practice Of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Bope E, Kellerman R, Schuller D. Conn’s Current Therapy 2018.; 2018.

- Kuhajda I et al: Lung abscess-etiology, diagnostic and treatment options. Ann Transl Med. 3(13):183, 2015