Author: Caleb Manasco MD, Michael Ip MD, and Braden McIntosh MD (Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center – New Orleans School of Medicine, Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Baton Rouge Campus, Baton Rouge, Louisiana) // Reviewed by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Cases:

Your first patient is a 67-year-old female who recently had glaucoma surgery 1 week ago presenting with 3 days of dull eye pain, blurry vision, and fevers up to 101.3F without other symptoms. Her visual acuity is 20/200 in the affected eye and is also injected. Your slit lamp exam is significant for a layering of white blood cells in the anterior chamber that fills approximately ¼ of the chamber. Just as you are about to tell her your plan for her, you hear a trauma activated overhead.

The patient is a healthy 21-year-old female who tripped and fell onto a glass table face first after a heavy day of drinking. She is in a C-collar with a GCS of 13. After verifying her airway, breathing, and vitals, you turn your attention to her HEENT exam. Her face has numerous small abrasions/bruises and a deep laceration that runs from her left nasolabial fold, through her left inferior and superior eyelid, and terminates just under the eyebrow. You gently open her eyelids and notice noticeable conjunctival hemorrhage and a teardrop pupil. The rest of your exam including a FAST is unremarkable for bruising or injury.

History:

In order to appropriately diagnose the red eye, a methodical, structured history and physical needs to be performed to narrow the differential diagnosis. In this article, we will only discuss the isolated red sclera. It does not include pathologies that involve the surrounding soft tissue (orbital cellulitis, blepharitis, etc.) A useful mnemonic to keep in mind all the emergent causes of red eye is HCG FUNKS: Hyphema/Hypopyon (endophthalmitis), Conjunctivitis/Conjunctival hemorrhage, Globe rupture, Foreign body, Uveitis/Ulcer, Narrow angle closure glaucoma, Keratitis (Herpes keratitis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, UV), and Scleritis. An important first question to ask is if the eye is painful or not. Painless conditions include hyphema, conjunctivitis, and conjunctival hemorrhage. Make sure to delineate between itchiness and pain as conjunctivitis can be pruritic. One caveat is that hyphema itself is not painful but can have associated painful conditions as this usually occurs in the setting of trauma. The remainder of the conditions above should have pain associated.

Another important question to ask if there is any subjective vision loss because it gives the examiner the degree of severity. In the context of a red eye, complete vision loss is very rare and associated with end stage endophthalmitis or narrow angle closure glaucoma. Partial visual loss or blurriness can be seen with the majority of the differential but should not be seen in conjunctivitis or conjunctival hemorrhage. Corneal ulcer, keratitis and hyphema only have associated vision loss if pathology is directly over the visual axis.

It is important to elicit what was the patient doing when the pain started, for instance any preceding trauma? Red eye relatively soon after trauma would indicate hyphema, a ruptured globe, foreign body, or traumatic uveitis. An occupational history should be elicited in all patients with ocular complaints as it can be very pertinent to the differential diagnoses. Specifically ask about operating machinery that would produce a projectile (metal on metal pounding, weedeating, metal grinding, etc.) as this could be the cause of foreign body and welding or skiing could be the cause of UV keratitis. Always ask about contact lens use as contact lenses put the patient at risk for Pseudomonas infections and would need appropriate antibiotics. Any recent ophthalmologic procedures should be asked as well as they heavily predispose the patient to having endophthalmitis.

A targeted review of systems can also help to pinpoint the differential diagnosis. If the patient has associated headache or nausea and vomiting, glaucoma should be evaluated as very few other causes of red eye have this association. Fever is worrisome for endophthalmitis and fairly specific in the context of the isolated red eye.

Physical Exam:

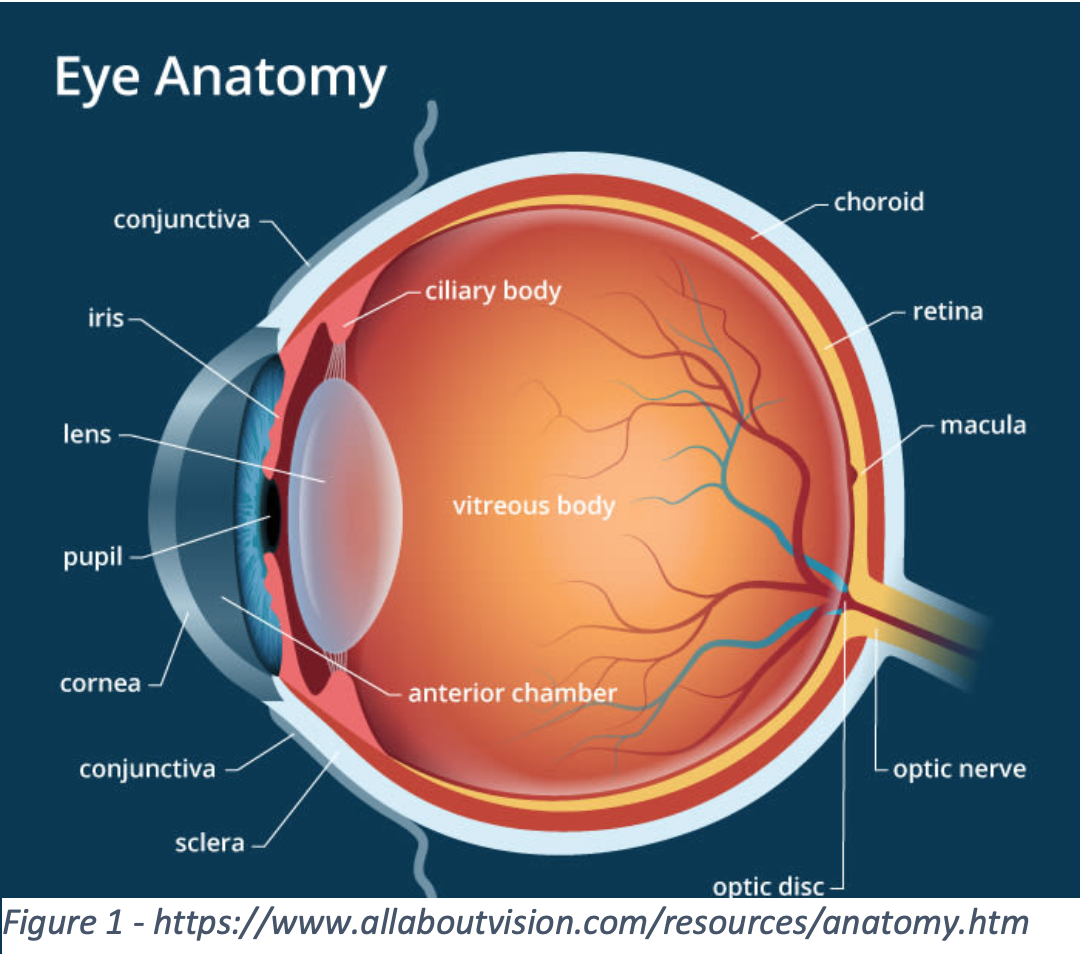

A quick review of anatomy will serve useful for understanding the pathology and treatment behind different causes of red eye. The pertinent anatomy to a red eye involves mostly preseptal, or anterior to the orbital septum. The most superficial layers, including the conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea, are akin to the skin of the body, forming the outer layer of the eye. Furthermore, they are also well vascularized and highly innervated; thus, any injury to these areas are injected and painful. The anterior chamber, bordered by the iris and cornea, is normally filled with clear  aqueous humor but can fill with blood or cells in certain conditions. Lastly, the iris, ciliary body, and choroid all collectively make up the uvea and are responsible for light focusing, aqueous humor production, and nutrient exchange for the eye.

aqueous humor but can fill with blood or cells in certain conditions. Lastly, the iris, ciliary body, and choroid all collectively make up the uvea and are responsible for light focusing, aqueous humor production, and nutrient exchange for the eye.

It is important to be methodical about your approach to the physical exam to ensure nothing is missed. The most important part of the physical exam is the visual acuity. For a standard Snellen eye chart, the patient is placed 20 feet from the chart. Visual acuity is defined as the smallest line a patient can read and get at least half of the letters correct. [1] Have the patient wear their glasses if they have them. If not, a pinhole can be created using an 18-gauge needle punched through paper to correct the patient’s vision. If the patient’s vision is worse than what can be read from the chart, detect finger counting, and if they cannot do this, test for motion, and finally light perception. If the patient’s vision is relatively intact, you should also assess visual fields as well as extraocular movements looking for defects and other disability. At this point any contacts should be removed for the remainder of the exam.

Next, assess for gross pupillary function. Look for an irregularly shaped pupil as this can represent specific differential such as ruptured globe, iritis, or, less commonly, glaucoma. The presence of consensual photophobia is also highly specific for uveitis and should be noted.  Next, look for the presence of ciliary flush. Ciliary flush is the inflammation of deep scleral vessels. It is not present in superficial causes of red eye, but it is present in inflammation of deeper structures and is classically associated with glaucoma and uveitis.

Next, look for the presence of ciliary flush. Ciliary flush is the inflammation of deep scleral vessels. It is not present in superficial causes of red eye, but it is present in inflammation of deeper structures and is classically associated with glaucoma and uveitis.

Apply a local anesthetic such as tetracaine at this point. Relief of pain with topical anesthetic also aids in diagnosis as relief will only be obtained with superficial pathology (e.g. foreign body/abrasion, keratitis, ulcer). Next fluorescein staining needs to be done to exclude ruptured globe as well as to assess for corneal abrasion, ulcer, or keratitis. Fluorescein staining needs to be done before Intraocular pressure (IOP) to rule out ruptured globe as measuring IOP can theoretically worsen ruptured globe. Evert the upper eyelid next with a cotton swab if signs of abrasion on fluorescein staining or foreign body sensation.

Assuming there are no contraindications to checking an intraocular pressure (IOP), this should be checked next and is the second most important vital sign of the eye, as IOP can rapidly diagnose glaucoma. Normal IOP is between 10-20 mm Hg. Very careful attention must be paid to not touch the eye in any way when opening the lids during measurement as this will falsely elevate the IOP. Touch the bony orbit only when retracting the eyelid.

A thorough discussion on proper use of the slit lamp exam and fundoscopy is outside the scope of this article and is best learned in person or through video. The slit lamp exam will be able to give you detailed information about conjunctiva and the anterior chamber. A fundoscopic exam, preferably with a pan optic ophthalmoscope and with dilation, may be helpful as well if you suspect posterior involvement.

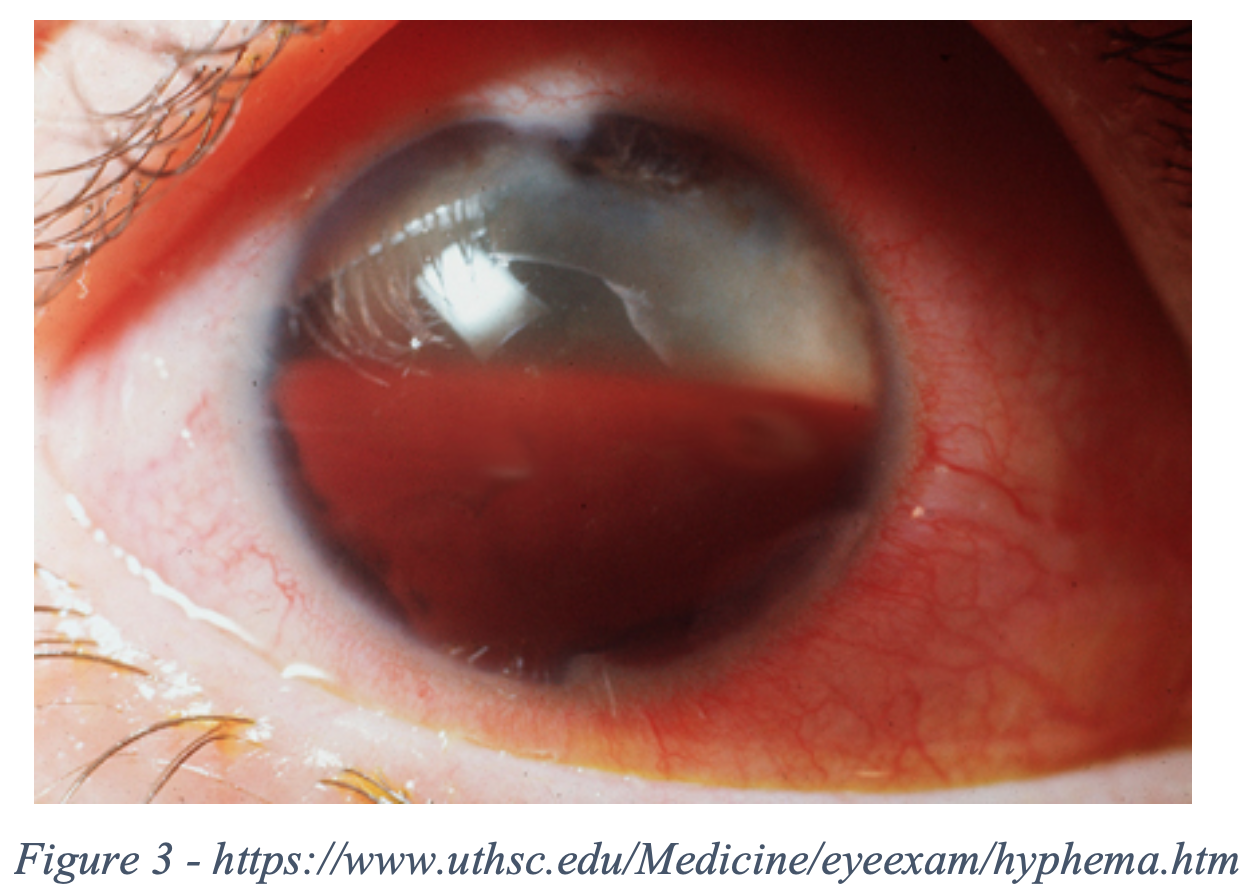

Hyphema

Hyphema refers to RBCs in the anterior chamber. The most common cause is trauma [1] and commonly occurs along with traumatic uveitis. Spontaneous hyphema can be caused by leukemia, coagulopathy, or sickle cell disease. All African Americans with spontaneous hyphema should be screened for sickle cell disease [2]. Complications of hyphema include clot formation leading to clogging of aqueous flow and increased IOP. Corneal staining can also occur and be permanent.

- History: Trauma? Medical history? Anticoagulants/antiplatelets? Recent ocular symptoms?

- Physical Exam: Slit lamp will show RBC in anterior chamber. A grading system is used and is based on height of hyphema:

- Grade I: Less than ⅓ height of anterior chamber

- Grade II: ⅓ to ½ of anterior chamber

- Grade III: ½ to total anterior chamber

- Grade IV (total hyphema/eight ball hyphema): Total filling of anterior chamber.

- Pearl* If bright red, it is referred to as a total hyphema. If dark red-black, it is called an 8-ball hyphema. The black color is suggestive of impaired aqueous circulation and decreased oxygen concentration. This distinction is important because an eight ball hyphema is more likely to cause pupillary block and secondary angle closure glaucoma [1].

- Workup (only if concern for coagulopathy): INR, PTT, platelets, +/- sickle cell screen.

- Management:

- Eye shield

- Elevate HOB (promotes layering of blood at base of anterior chamber below visual axis)

- Avoid anticoagulants/antiplatelets (including NSAIDs)

- +/- correct coagulopathy (need to weigh risk vs reward of reversing if patient is on anticoagulant with ophtho and appropriate specialist who prescribed anticoagulant)

- Treatment:

- Cycloplegics reduce “pupillary play” (the dilation and constriction of the pupil) and reduce pain and theoretically reduce possible disturbance of clot causing rebleed.

- If elevated IOP (>30 mm Hg in non-sickle cell and > 24 mm Hg in sickle cell patients), can treat similarly to glaucoma (refer to glaucoma section). Avoid carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in sickle cell patients as this can theoretically cause promotion of sickling due to metabolic acidosis

- Disposition:

- Consult ophtho for possible admission for high grade hyphema (grade III or IV), coagulopathic or sickle cell patient, or elevated IOP. If intractable elevated IOP despite medical therapy may need surgery.

- No high-risk features requiring admission: Urgent outpatient follow up with ophtho, discharge with eye shield and instruct to keep HOB elevated.

Endophthalmitis (Hypopyon)

Endophthalmitis is an infection of the deep structures in the eye, particularly the aqueous and vitreous humor. It is very dangerous as it can rapidly lead to permanent vision loss. The most common cause is after ocular surgery and next most common is direct penetrating trauma [1]. Rarely endophthalmitis can be caused from hematogenous spread and present with sepsis. For surgical causes, the onset of symptoms occurs within 1 week in 75% of cases [3]. The overwhelming majority of pathogens are gram (+) [4],however due to the increased virulence of gram (-) organisms, broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered. Definite treatment includes intravitreal injection of vancomycin and ceftazidime and possibly vitrectomy if medical treatment fails. The role of systemic antibiotics is unclear in the literature, but it is reasonable to administer IV antibiotics in the ED before ophtho can provide definitive care.

- History: Recent symptoms? Trauma? Fever? Vision loss (3% of patients report blurred vision) [5] Eye pain?

- Physical Exam: Slit lamp will show cell and flare in anterior chamber and hypopyon

- > *Pearl* only 75% of presentations will have hypopyon on presentation [6]

- Workup: Septic workup if indicated (CBC, lactic acid, Blood cultures, etc.)

- Treatment: +/- Vancomycin loading dose 25mg/kg (Max dose 2g) IV or Linezolid 600mg IV + ceftazidime 50mg/kg (max dose 2g) IV

- > *Pearl* Linezolid has better tissue penetration compared to vancomycin and may provide a theoretical benefit to reaching adequate drug concentration levels in the vitreous humor of the eye.

- Disposition: Call ophtho and admit for intravitreal antibiotics, +/- vitrectomy

Conjunctivitis

Bacterial

Conjunctivitis is defined simply as an inflammation of the conjunctiva. The conjunctiva is a sensitive part of the body; thus many things can cause conjunctivitis. Bacterial conjunctivitis is the diagnosis to not miss. Most commonly it is caused by S. Aureus, S. Pneumoniae, H. Influenza [1]

- History – foreign body sensation, conjunctival injection, eye discharge, sick contacts with eye symptoms

- Physical Exam – conjunctival injection with perilimbal sparing, starts unilaterally and can spread bilaterally. In severe cases it can spread within hours with copious purulent drainage, chemosis and is usually without lymphadenopathy except in cases of gonococcal infections. Be sure to ask about sexual history. [7]

- Chlamydia – can look for PNA/staccato cough, OM, proctitis, vulvovaginitis

- Gonococcal – Like chlamydia, GC is often associated with genital lesions.

- Treatment – Non-contact lens wearer and do not suspect Gonorrhea/chlamydia: erythromycin ointment 4x daily for 5-7 days or polymyxin B/trimethoprim 1-2 ggt every 3-6 hours for 7-10 days [1]

- Contacts: pseudomonas coverage with fluoroquinolone drops 1-2 ggt every 2 hours while awake for 2 days then every 4-8 hours for 5 days. Discard contacts and wear glasses only. Can resume once antibiotics are complete and no discharge for 24 hrs.

- Gonorrhea – ceftriaxone 1 g IM/IV once + Azithromycin 1 g PO once + ophtho consult for follow-up + treat partners

- Chlamydia – Azithromycin 1 g PO once or Doxycycline 100mg PO BID x 7 days or Erythromycin 500mg 4x daily for 7 days + ophtho consult for follow-up + treat partners

Viral

The more common form of conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis is most often caused by adenovirus and is self-limiting; however, it is highly contagious. The presence of preauricular lymphadenopathy can help differentiate viral from bacterial conjunctivitis [1].

- History – watery eye discharge. Usually bilateral. Ask about sick contacts

- Physical Exam – Conjunctival injection with perilimbal sparing, may have chemosis

- Treatment – cool compresses, artificial tears, topical antihistamines for symptomatic treatment. Abx can still be given to prevent superinfection but not necessary

Neonatal

Neonatal conjunctivitis is defined as conjunctivitis in babies less than 30 days old. Mothers should be asked about the birth history for example if the mother had prenatal care or if the infant was born at home as this increases risk of transmission of microorganisms. STD history of the mother should also be elicited and if the child was born outside the country as not all other countries administer erythromycin to the infant’s eyes at birth. It is best diagnosed through the timeline of when the symptoms started in reference to date of birth.

- Chemical: Occurs on the 1st day of life and is caused by application of erythromycin ointment. Will self-resolve after 48 hours.

- Gonococcal: 2-7 (usually 3-5) days after birth and has profuse bilateral purulent discharge. Is associated with meningitis and sepsis.

- Workup: Full septic workup including CSF studies, UA with culture, blood culture, culture of the eye [1]

- Treatment: Cefotaxime 100mg/kg IV every 8 hours.

- Disposition: Consult ophtho and admit for septic workup and IV antibiotics

- Chlamydial: 5-14 (usually 7-10) days after birth. Can be associated with chlamydial pneumonia.

- Workup: Chlamydial NAAT of eye, CXR if cough, hypoxia

- Treatment: Erythromycin 12.5mg/kg PO every 6 hours x 14 days [8]

- > *Pearl* Erythromycin can increase the risk of developing pyloric stenosis in children less than 2 weeks of age and parents should be warned of this possible side effect [9].

- Disposition: Consult ophtho with likely discharge and follow up in 24 hours

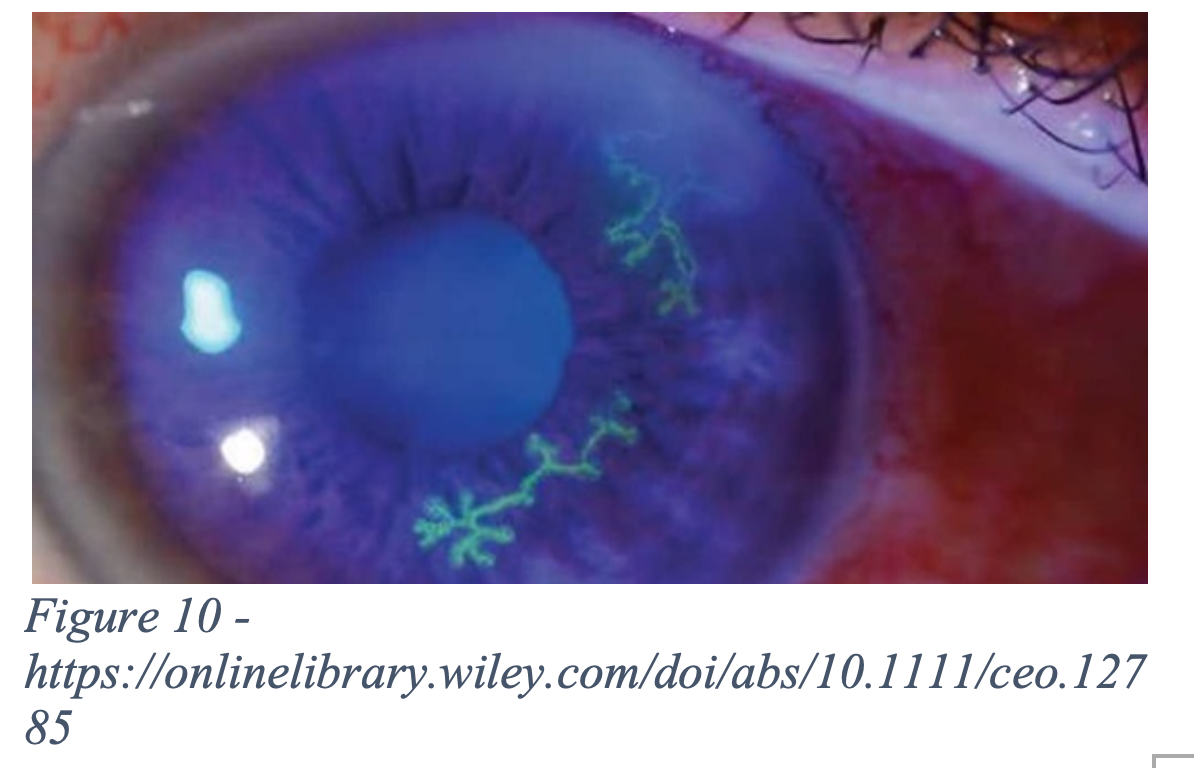

- HSV: 14-28 days after birth. Usually obtained upon exiting the vagina through delivery. Can be associated with meningitis and disseminated HSV. Physical exam will show dendritic lesions on fluorescein staining.

- Workup: Full septic workup including CSF studies, Urinalysis/urine cultures, blood cultures, and viral cultures of the eye, mouth, nasopharynx, rectum, and from any vesicles on the skin

- Treatment: Acyclovir 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours for 21 days + topical 1% trifluridine or1% iododeoxyuridine, or 0.15% ganciclovir [10]

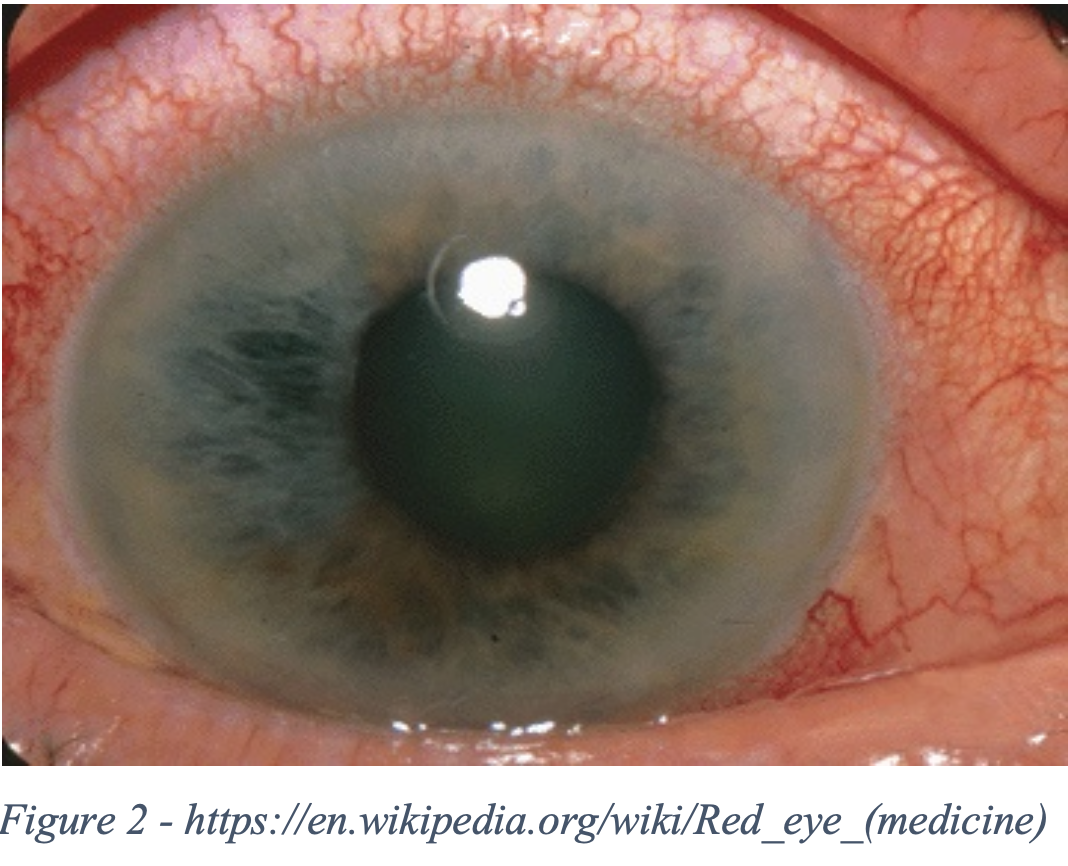

Subconjunctival hemorrhage

- History – red patch of bleeding in scleral distribution [1] Usually a traumatic event or one that leads to increased IOP (e.g. sneezing). If young or nursing home pt, consider abuse. If on anticoagulation, consider checking coag levels [11].

- Physical exam – slit lamp to rule out involvement of other parts of the eye. Usually limbus sparing (as opposed to iritis). If suspect abuse, perform fundoscopic exam to evaluate for retinal hemorrhages

- Treatment – will self-resolve in 2-3 weeks

Globe rupture

A globe rupture is a full thickness tear of the eye and can be blunt or penetrating. If blunt, locations of globe rupture tend to occur where the eye is weakest at the limbus and at the posterior portion of the globe where the rectus muscles attach [1]. High speed projectiles can penetrate the eye and the cornea can seal off, making injury nearly undetectable on visual inspection. As soon as globe rupture is suspected obtain a visual acuity, stop the physical exam at that point, and consult ophthalmology immediately.

- History: Vision loss? High velocity projectile?

- Physical Exam: Obvious causes will show internal prolapse of iris or vitreous. Seidel’s sign on fluorescein staining is pathognomonic for rupture. Other findings that point to rupture include [12]:

- Extensive subconjunctival hemorrhage/chemosis

- Teardrop pupil (pupil will point toward rupture)

- Shallow or deep anterior chamber compared to contralateral eye

- >>*Pearl* Anterior chamber will be shallow in anterior rupture due to loss of anterior internal contents and deep in posterior rupture due to contents of interior eye being pulled away from cornea.

- Workup: CT non contrast with 1-2 mm slices only for detecting penetrating foreign body or if concern for non-obvious posterior ocular rupture.

- >*Pearl* CT scan for diagnosis of open globe has very poor sensitivity (51%-77%), but excellent specificity (>97%) [13].

- Management:

- Eye shield that only touches bony orbit (Fox shield)

- Elevate HOB

- Treatment:

- Prophylactic antiemetics to prevent increased IOP

- Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent endophthalmitis: Vancomycin loading dose 25mg/kg (Max dose 2g) IV orLinezolid 600mg IV + Ceftazidime 50mg/kg (max dose 2g) IV

- Tetanus vaccine if not up to date

- Disposition: Consult ophtho immediately for surgical repair.

Foreign body

Corneal abrasions are defined as a defect to the corneal surface epithelium, most commonly due to a traumatic etiology, from nails and contacts to particulate matter (sawdust, grass). Approximately 3% of all ED visits are due to eye trauma, ~80% of which are due to foreign bodies/corneal abrasions. This is especially common in working ages from 20-29 years old and has a significant economic effect with lost work days and medical visits. Often associated with traumatic uveitis if not treated immediately [1].

- History: eye pain, foreign body sensation, hyperemia, as the conjunctiva is a highly vascularized and innervated region. [14]

- Physical Exam: numb the eye with tetracaine (diagnostic and therapeutic step) and fluorescein stain, preferably under a slit lamp

- > *Pearl* Wood’s lamp has sensitivity of 52% when compared to slit lamp in identifying ocular pathology and 56% sensitivity for corneal abrasions specifically [15].

-

- Evaluate for % involvement of the abrasion if present.

- Rule out deeper involvement that might need CT non contrast of orbits 1-2mm slices or immediate ophtho consult (e.g. corneal lac, globe rupture) by looking for Seidel’s sign

- Rule out foreign bodies. Don’t forget to evert eyelids to check for embedded foreign bodies there, especially if “ice rink” sign is present (see figure 6). If present on the cornea, a blunt tip needle, cotton swab, or eye burr can be used for removal with guidance of the slit lamp

- Disposition/management – these heal in 24 to 48 hours, so have the patient follow up with ophthalmology in that time window outpatient.

- Pain control – NSAIDs (oral vs ophthalmic) or cycloplegics, which prevent ciliary body spasms (Cyclopentolate 1% or homatropine 5% 1 drop 1-2 times per day).

- However, cycloplegics do not block the sensation of irritation or pain, and the evidence for ketorolac drop analgesia efficacy is weak at best [4].

- Tetracaine drops – extremely controversial, most recent data suggests that 24-hour use does not increase the risk of corneal ulcerations as thought before [16-19].

- Ophthalmic antibiotics –

- Erythromycin ointment 4x daily for 3-5 days for non-contact wearers

- Levofloxacin, Moxifloxacin, and Ofloxacin all 1-2 ggt every 2 hours while awake for 2 days then every 4-8 hours for 5 days for contact wearers for pseudomonas coverage.

- Consult ophthalmology for emergency department vs same day office eval for –

- >50% involvement

- hypopyon/hyphema

- persistent foreign body

- purulent discharge

- significant decrease in visual acuity (more than 1 line on Snellen chart)

- nonhealing/expanding abrasion

- Pain control – NSAIDs (oral vs ophthalmic) or cycloplegics, which prevent ciliary body spasms (Cyclopentolate 1% or homatropine 5% 1 drop 1-2 times per day).

Uveitis

The first of the inflammation type diseases, uveitis, or an inflammation of the uvea, is responsible for approximately 10% of blindness in the Western world. As a reminder, the uvea consists of the ciliary body, iris, and choroid most commonly but can also involve the retina, vitreous humor, and optic nerve if posterior enough. You may hear of iritis and iridocyclitis, but uveitis has superseded those terms and is used more frequently as of late.

Uveitis is caused mostly by either traumas, infections or autoimmune causes, most of which are idiopathic/autoimmune [1] Examples include HSV, VZV, TB, CMV, Syphilis, Sarcoidosis, IBD, ankylosing spondylitis, Bechet’s disease, multiple sclerosis, JIA, Kawasaki’s disease [20,21].

- History: Painful eye, +/- photophobia and blurry vision [22, 23]

-

- Posterior involvement may not have any of these symptoms and only present with floaters/vision loss

- Physical Exam: Conjunctival injection with ciliary flush, irregular/small pupil asymmetrically as pupil spasms or adheres to lens.

-

- You will see cell and flare and hypopyon on slit lamp exam in cases that involve the anterior chamber

- Consensual photophobia is fairly specific and helps separate uveitis from superficial conjunctival irritation as the uvea is heavily involved in pupillary contraction [23]

- Treatment: treat infection if present (e.g. antivirals, antibiotics) [22]

-

- Autoimmune tests – HLA, HIV, CXR (sarcoidosis/TB) and syphilis test if no other suspected cause

- Consider topical steroids – prednisolone acetate 1%

- Consider cyclopentolate for ciliary spasm relief and prevention

- Systemic steroids/immunologics only for refractory cases

- Urgent ophthalmology follow up

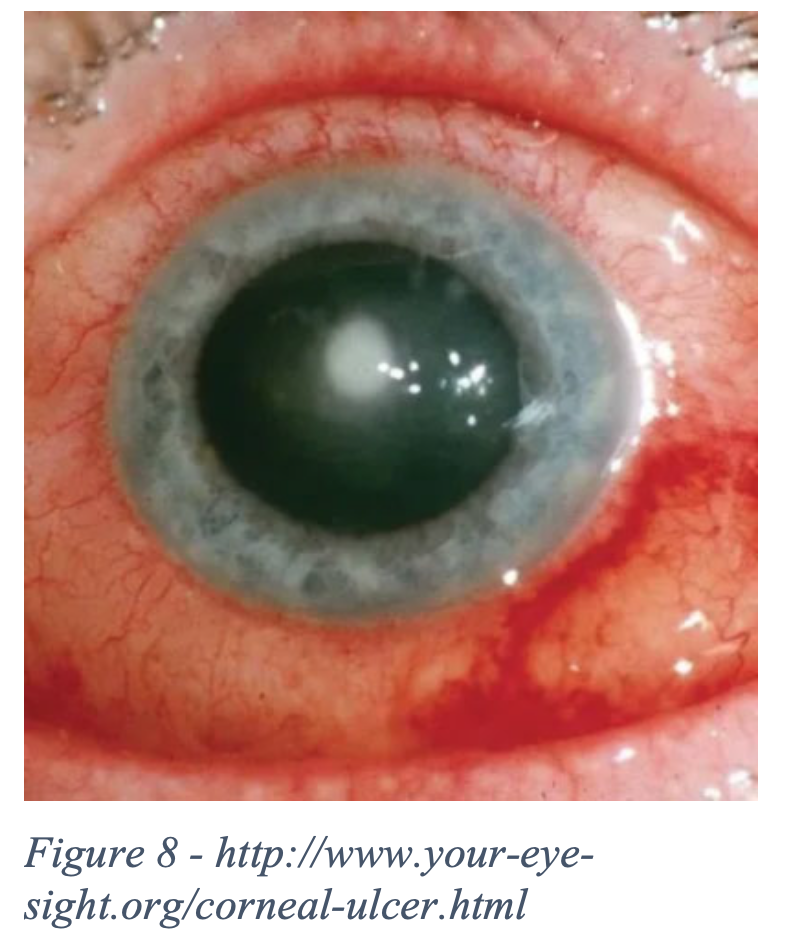

Ulcer (bacterial keratitis)

A corneal ulcer is a local necrosis of corneal tissue that goes through the epithelium and stroma usually caused by bacteria, virus, or fungi. Should be presumed bacterial until proven otherwise due to rapid spread and can lead to vision loss if not treated promptly. Risk factors include wearing contact lenses and trauma. Diagnosis is made clinically and is usually evident on visual inspection. Physical Exam will reveal an opaque gray/white lesion on the patient’s cornea. It is important to note if it is within the patient’s visual field and the size of the ulcer so this measurement can be compared when the patient is evaluated later. Can have associated iritis. [24]

- History: Trauma? Contact lens use? Dry eyes? Vision changes? Pt will classically complain of fb sensation.

- Physical Exam: unilateral, will have fluorescein uptake over ulcer. May have associated hypopyon. Obtain measurement of ulcer during exam [25].

- Treatment:

- Small, peripheral ulcer: Ciprofloxacin 1 ggt qhour or moxifloxacin 1 ggt qhour or ofloxacin 1 ggt qhour

- Large, vision threatening ulcer: Fortified (14mg/ml) Tobramycin or fortified (15mg/ml) Gentamicin 1 ggt every hour around the clock alternating with fortified (25mg/ml) Vancomycin 1 ggt qhour [1]

- > *Pearl* These fortified drops are not commercially available and need to be made at a compounding pharmacy

- +/- Cycloplegics if concomitant iritis

- Disposition: Emergent ophtho consultation. Follow ophtho recommendations on antibiotic coverage. If not seen in ED by ophtho will need follow up within 24 hours. Suspend contact use until fully resolved.

Narrow angle closure glaucoma

Narrow angle closure glaucoma is defined as glaucoma from narrowing/closure of anterior chamber angle (usually due to pupillary block), leading to inadequate drainage of aqueous humor and ultimately atrophy/neuropathy of optic nerve head secondary to increased intraocular pressure (IOP). This is one of the big causes of red painful eye that we don’t want to miss as this is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally. Risk factors include family history, age >60 years, female sex, medications, Inuit/Asian race, and certain medications. [26]

- History: sudden onset eye pain, blurred vision, nausea/vomiting/abdominal pain, Headache, haloes.

- Precipitating factors – transition to dim lighting, sympathomimetics (including cough medications), antidepressants, steroids, anticonvulsants, anticholinergics, sympathomimetics

- Physical Exam:

- Obtain intraocular pressure bilaterally (suspect when >20, definitely >30 mmHg), visual acuity, pupil eval but don’t perform pupil dilation in untreated cases since it may worsen condition. Perform slit lamp exam

- Will note conjunctival injection with ciliary flush, nonreactive mid-dilated pupil, corneal haze, IOP elevated [28]

- Treatment:

- Treatment summary/order [1]:

- First – 1 gtt each of 0.5% timolol + 1% apraclonidine or 0.2% brimonidine + latanoprost. Repeat once more in 30 minutes if IOP still elevated

- When IOP<40 – 2% pilocarpine 1 gtt 15 minutes apart x 2 doses then qid

- If refractory – Acetazolamide 500 mg IV/PO or mannitol 1-2 g/kg IV

- +/- supine, steroids

- Recheck IOPs every hour

- Treatment summary/order [1]:

-

- Mnemonic STAMP

- Supine position – lens moves posteriorly, helping relieve pupil block [28] although there is conflicting data on supine vs HOB elevation

- Steroids – very controversial especially since steroids can increase IOP in pts, only with ophtho on board. Usually used to control inflammation after initial attack. Prednisolone q15 minutes x 4 doses [30]

- Timolol – beta blocker, decreases aqueous humor production on ciliary epithelium

- A2 agonist – 1% Apraclonidine or 0.2% brimonidine, decreases aqueous humor production [29]

- Acetazolamide – carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, decreases aqueous humor production.

- Contraindicated in renal failure and sickle cell pts

- Mannitol – in severe/refractory cases, can reduce volume of vitreous humor via osmotic diuresis.

- Contraindicated in renal failure pts.

- Prostaglandin (i.e. latanoprost) – increases flow through trabecular meshwork

- Pilocarpine –

- muscarinic agonist leading iris to contract pulling away from trabecular network, increases aqueous humor drainage by constricting pupil.

- Start after other drugs as you may have ischemic paralysis which prevents pilocarpine efficacy [27,28]

- Mnemonic STAMP

- Management/Disposition:

- emergent ophthalmology consult – if medical therapy fails, ophtho will perform a peripheral iridotomy (which creates a second connection from posterior to anterior chamber) or anterior chamber paracentesis

- check pressures q30-60minutes, keep in a well-lit room.

Keratitis (Herpes keratitis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, UV)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis

HSV keratitis is caused by the herpes simplex virus and is an infection of the cornea. The virus remains in the trigeminal nerve when inactive and patients can have reactivations of the virus for the remainder of their life. Immunocompromised patients are at more risk for reactivation of disease. HSV is a serious infection and can lead to permanent vision loss if not treated promptly. Diagnosis is usually clinical and made on fluorescein exam.

- History: Previous episodes of HSV? Immunocompromised (HIV, chronic use of corticosteroids etc.)? Vision loss/blurriness?

- Physical Exam: Fluorescein stain will show dendritic lesions on cornea that have terminal bulbs

- Treatment: Acyclovir 400mg PO 5x daily or Valacyclovir 500mg PO TID for 10-14 days

- Renally dose for kidney patients

- Disposition: Ophthalmology follow-up within 7 days

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO)

Similar to HSV keratitis, but instead is caused by varicella zoster virus that is reactivated in the V1 nerve distribution. Does not necessarily involve the cornea, but the cornea is involved in ~50% of cases. Typically affects the older population as immunity wanes. Immunosuppression is a major risk factor that can induce a reactivation as well. Systemic symptoms can also be seen such as fever, fatigue, malaise; however, fewer than 20% of patients will have these symptoms [31].

- History: Immunocompromised? Fever? Vision loss?

- Physical Exam: There will be vesicular lesions that morph into crusted lesions on the skin that follow along V1 distribution. Fluorescein will show poorly staining pseudodendrites without a terminal bulb.

- >*Pearl* Hutchinson sign is when there is a vesicle is on the tip of the nose. This correlates very strongly with a corneal lesion as the nasociliary branch of V1 innervates both the tip of the nose and the cornea.

- Treatment:

- If immunocompetent and only one dermatome: Acyclovir 800 mg PO 5x daily or famciclovir 500 mg PO TID or valacyclovir 1 g PO TID – all for 7-10 days [32]

- If immunocompromised or severe life-threatening infection or multiple dermatomes: acyclovir 10mg/kg IV TID x 7 days.

- Disposition: Admit if immunocompromised or severe eye involvement or multiple dermatomal distributions to receive IV acyclovir. Otherwise, can follow up with ophthalmology within 1 week.

Ultraviolet keratitis (Photokeratitis)

UV keratitis is caused by prolonged UV light on the cornea. Damage is cumulative so multiple short exposures can be equally as damaging as one prolonged exposure [1]. Pain is not immediate and is delayed to approximately 6-12 hours. Resolution occurs spontaneously once removed from the offending source at approximately 24-72 hours.

- History: Occupation, hobbies (welders, snow blindness, tanning booth)

- Physical Exam: Punctate fluorescein uptake on slit lamp that spares palpebral conjunctiva

- Treatment: PO NSAIDs and/or opioids for pain.

- Antibiotics are often prescribed for comfort and prevent bacterial super-infection but are not necessary. Can use erythromycin ointment 1 ribbon qid x 3 days

- Disposition: Discharge. Instruct to discontinue UV exposure for at least 72 hours and suspend contact use until fully resolved

Scleritis/episcleritis

Marked usually by painful destructive and blinding, scleritis, or inflammation of the sclera is usually clinically diagnosed and associated with infectious, trauma, or autoimmune/inflammatory disorders. The most common association is with rheumatoid arthritis, but also consider lupus, scleroderma, or Wegener’s granulomatosis. There are different types of scleritis – diffuse, nodular, and necrotizing. Diffuse and nodular are most common, and necrotizing is most severe. [33]

Of note, episcleritis is the more common and benign form of scleral irritation, involving only the episcleral vessels. There are also diffuse and nodular forms, and idiopathic vs autoimmune are still the most common causes. We will focus more on scleritis, as episcleritis is usually self-resolving and scleritis has more urgent management requirements, but we will add key differentiating factors between the two.

- History – classic presentation of slow onset, severe constant boring ocular pain worse at night/early morning to eyes or face. +/- headache, watering of eye, photophobia, pain on eye movement [35]

- If nodular, will see localized areas of firm tenderness and intense dilation of scleral vessels

- If necrotizing, can see bulging of inflamed sclera as it thins from necrosis. May also have no pain secondary to destruction of nerves (aka scleromalacia perforans)

- Physical Exam – look for violaceous conjunctival involvement. Pt will have local tenderness on palpation (with eyelid closed, exert mild pressure) [1]

- Episcleritis has more of a reddish radial vascular pattern. Furthermore, mobile vessels with a cotton swab or blanching with phenylephrine drops are more suggestive of episcleritis [34].

- Posterior scleritis is very difficult to pick up due to location, may notice diplopia and pain on movement. On slit exam, can have retinal or choroid abnormalities.

- Ultrasound/CT may help with ruling out involvement of other structures of the eye

- Treatment – in conjunction with consultants. admission.

- Start with systemic NSAIDs – indomethacin 50 mg TID [34]

- If more severe, most respond to high dose prednisone 1 mg/kg/day up to 80 mg

- If necrotizing or refractory to steroids, should add on immunosuppressants i.e. cyclophosphamide or rituximab

- Management –

- ophthalmology and rheumatology consults and admission

- Inflammatory markers (CRP ESR), autoimmune panel (ANA, ANCA etc.), CXR to r/o infiltrates/infections leading to vasculitis

Back to the Cases

As you wrap up the trauma activation, you perform a visual acuity but do no further ophthalmologic examination. You order a CT head, sinus/face with specification for 1-2mm cuts at orbits, c-spine, and you elevate the HOB and place an eye shield on the patient’s eye. While with the patient in the CT scanner, you emergently page ophthalmology, who look at the images and agree to evaluate the patient for emergent surgical repair.

Right before she tries to hang up, you inform the ophthalmologist about your patient in room 1, who you suspect has endophthalmitis due to her signs of sepsis, post op status, and hypopyon. She agrees to call her partner in to evaluate room 1 and asks you to start antibiotics after your sepsis workup. You order linezolid + ceftazidime and update the patient that she will be admitted for further treatment.

Key Takeaways:

- Always have a broad differential on evaluation of the red eye (HCG FUNKS). A detailed history may help you diagnose the pathology and the cause behind it, which can save time and effort.

- Consider autoimmune disease in patients with systemic complaints or unclear etiology when diagnosing eye pathology.

- The importance of a complete eye exam cannot be understated. This includes visual acuity, pupil exam, intraocular pressure, fundoscopy, and slit lamp exam with fluorescein if not contraindicated.

- Delayed treatment/consultation with ophthalmology can lead to serious morbidity.

- Use of the slit lamp is vital to diagnosing many emergent causes of red eye and is expected of us from our ophthalmology colleagues.

References:

- Stapczynski JS, Tintinalli JE. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Oldham G, Syed Z. Hyphema. EyeWiki website. https://eyewiki.org/Hyphema. January 24, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- Taban M, Behrens A, Newcomb RL, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systemic review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol 2005; 123:613.

- Kernt M, Kampik A. Endophthalmitis: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, management, and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:121-135

- Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:1479–1496.

- Mamalis N. Endophthalmitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(5):729–730.

- Simon E. Bacterial Conjunctivitis. emDocs Website. http://www.emdocs.net/em3am-bacterial-conjunctivitis/. June 4, 2017. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Chlamydia trachomatis. In: Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 31st ed, Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS (Eds), American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL 2018. P.276.

- Eberly MD, Eide MB, Thompson JL, Nylund CM. Azithromycin in early infancy and pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics 2015; 135:483.

- Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, et al (ed): Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015.

- Mimura T, Usui T, Yamagami S, et al. Recent causes of subconjunctival hemorrhage. Ophthalmologica 2010; 224:133.

- Kuhn F, Pelayes D. Management of the Ruptured Eye. European Ophthalmic Review 2009. 3(1):48-50.

- Crowell EL et al. Accuracy of computed tomography imaging criteria in the diagnosis of adult open globe injuries by neuroradiology and ophthalmology. Acad Emerg Med 2017 Jun 29.

- Willmann D, Moshirfar M, Melanson SW. Corneal Injury. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459283/

- Hooker EA, Faulkner WJ, Kelly LD, Whitford RC. Prospective study of the sensitivity of the Wood’s lamp for common eye abnormalities. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(3):159. Epub 2019 Jan 10.

- Wakai A, Lawrenson JG, Lawrenson AL, Wang Y, Brown MD, Quirke M, Ghandour O, McCormick R, Walsh CD, Amayem A, Lang E, Harrison N. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD009781. Epub 2017 May 18.

- Puls HA, Cabrera D, Murad MH, et al. Safety and effectiveness of topical anesthetics in corneal abrasions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(5):816-824.

- Swaminathan A, Otterness K, Milne K, et al. The safety of topical anesthetics in the treatment of corneal abrasions: a review. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(5):810-815.

- Waldman N, Winrow B, Densie I, et al. An observational study to determine whether routinely sending patients home with a 24-hour supply of topical tetracaine from the emergency department for simple corneal abrasion pain is potentially safe. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(6):767-778.

- Guly, Catherine M and Forrester, John V. Investigation and Management of Uveitis. BMJ 2010; 341:c4976.

- Rosenbaum JT. Acute anterior uveitis and spondyloarthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1992;19(1):143.

- Murphy T. Minor Care Series: Uveitis. tamingthesru.com/blog/bread-butter-em/uveitis. April 2, 2018. Accessed April 30 2020.

- Gilani CJ, Yang A, Yonkers M, Boysen-Osborn M. Differentiating Urgent and Emergent Causes of Acute Red Eye for the Emergency Physician. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(3):509‐517. doi:10.5811/westjem.2016.12.31798

- Bartolomei A, Nallasamy N. Bacterial Keratitis. EyeWiki Website. https://eyewiki.org/Bacterial_Keratitis. Oct 13, 2019. Accessed April 30 2020.

- Weymouth W, Simon E. EM@3AM – Corneal Ulcer. emdocs.net/em3am-corneal-ulcer/. Aug 5, 2017. Accessed May 1, 2020.

- Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081. Epub 2014 Jun 26.

- Yanoff, M., Duker, J. S., & Augsburger, J. J. Ophthalmology, 2014. Saunders Elsevier, 1084-1089.

- Murray D. Emergency management: angle-closure glaucoma. Community Eye Health. 2018;31(103):64.

- Schadlu R, Maus TL, Nau C. Comparison of the Efficacy of Apraclonidine and Brimonidine as Aqueous Suppressants in Humans. Arch Opthalmol. 1998;116(11):1441-1444. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.11.1441

- Fellman R. Steroids for Glaucoma: Both Friend and Foe. Review of Opthalmology website. https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/ steroids-for-glaucoma–both-friend-and-foe. September 8, 2015. Accessed 4/20/2020.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breur J. et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44 Suppl 1:S1

- Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology 1991; 98:1216.

- Okhravi N, Odufuwa B, McCluskey P, Lightman S. Scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(4):351.

- Jabs DA, Mudan A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ. Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000; 130(4): 469.

- Summers J. Scleritis and Episcleritis. Taming the SRU. http://www.tamingthesru.com/blog/bread-butter-em/scleritis-and-episcleritis. Feb 7, 2018. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

1 thought on “Approach to the Red Eye”

Pingback: Weekend Knowledge Dump- September 11, 2020 | Active Response Training