Authors: Zain Talukdar MD (Pediatric Resident Physician, University of Chicago); Kimberly Schwartz, MD (Clinical Associate, Pediatrics, Child Abuse Pediatrics) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 3-month-old previously healthy male is brought to the ED by his parents. His father says he rolled off the couch onto a hardwood floor, started crying immediately, and then seemed sleepy and more fussy than usual. On exam, the patient is minimally consolable with a small bruise on his left forehead. Vitals are stable. There are no palpable skull fractures. Due to the age and mechanism, you obtain a head CT which shows a subdural hematoma without midline shift. You obtain a skeletal survey which shows a healing posterior rib fracture.

Question: What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Pediatric Non-Accidental Trauma (NAT)

Epidemiology

- The fatality rate stemming from NAT in the United States (US) is estimated at 1.05 children per 100,000, which translates to approximately one to two deaths per day.1

- A quarter of all cases occur in children under one year of age.1

- Overwhelmingly caused by parental figures.

- 38% mothers, 23.9% fathers, 20.0% both parents.

- Linked to but not specifically caused by parental stress, family history of psychological disorders, personal history of intimate partner violence (IPV), victim of childhood trauma, substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Also consider other social stressors like financial hardship, inadequate housing, food insecurity, history of criminal background, reliance on public assistance.1

Presenting Symptoms/Injury pattern

- Nonspecific, wide spectrum of signs and symptoms.

- Strongest historical predictor is incongruence between HPI and patient presentation.2

- Consider mechanisms that don’t align with developmental age, delays in seeking medical care, inconsistencies with stories.

- Typically, there are no or minimal neurologic symptoms from a short fall from couch height.

- For infants => Sentinel injury: visible or detectable minor injury in a pre-cruising infant that is poorly explained and therefore suspicious for physical abuse3 recedes abuse in 27.5% of cases of NAT, can be a missed opportunity to catch NA.

- Pre-cruising infant

- Visible or detectable to caregiver

- Poorly explained and unexpected

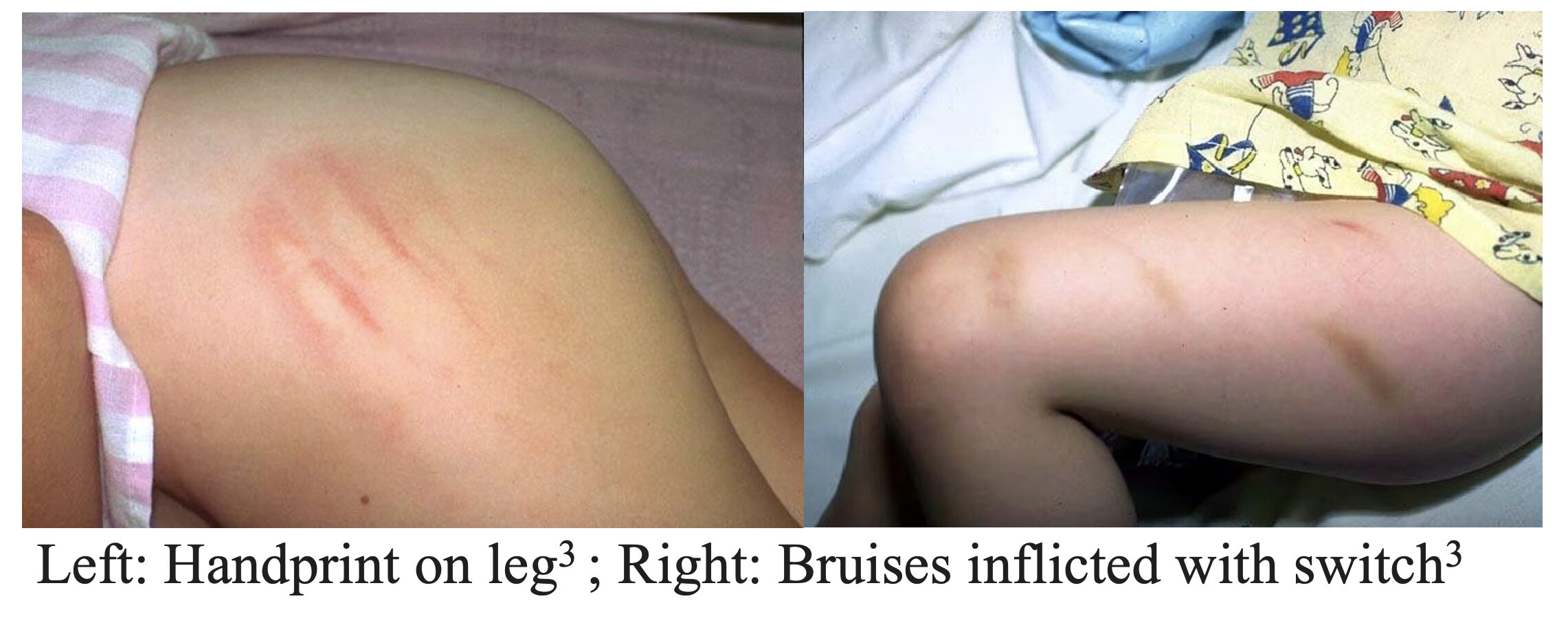

Bruise or intraoral injury

- Most common form of NAT.

- Intraoral injury: frenulum tears in non-ambulatory child (common in toddlers) or an unexplained injury to lips/teeth/soft palate.

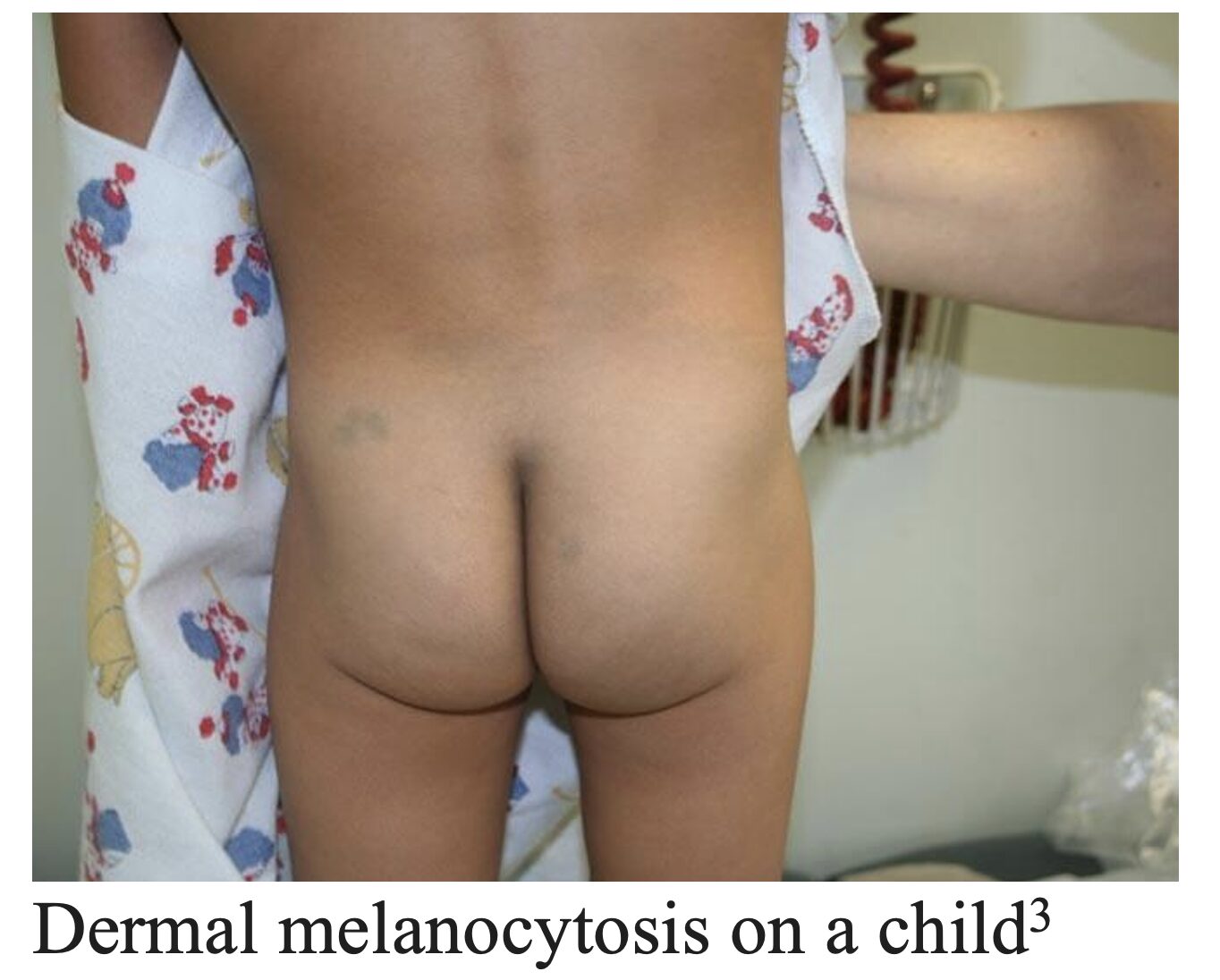

- Mimics/Differential Diagnosis: accidental bruising in ambulatory child (forehead, shins, knees), coagulopathies (Factor V Leiden, von Willebrand), disorders of collagen (Ehlers-Danlos), dermal melanocytosis (formerly known as Mongolian spot), coin rubbing/cupping/moxibustion (cultural practices), port-wine stains (HSP, ITP).

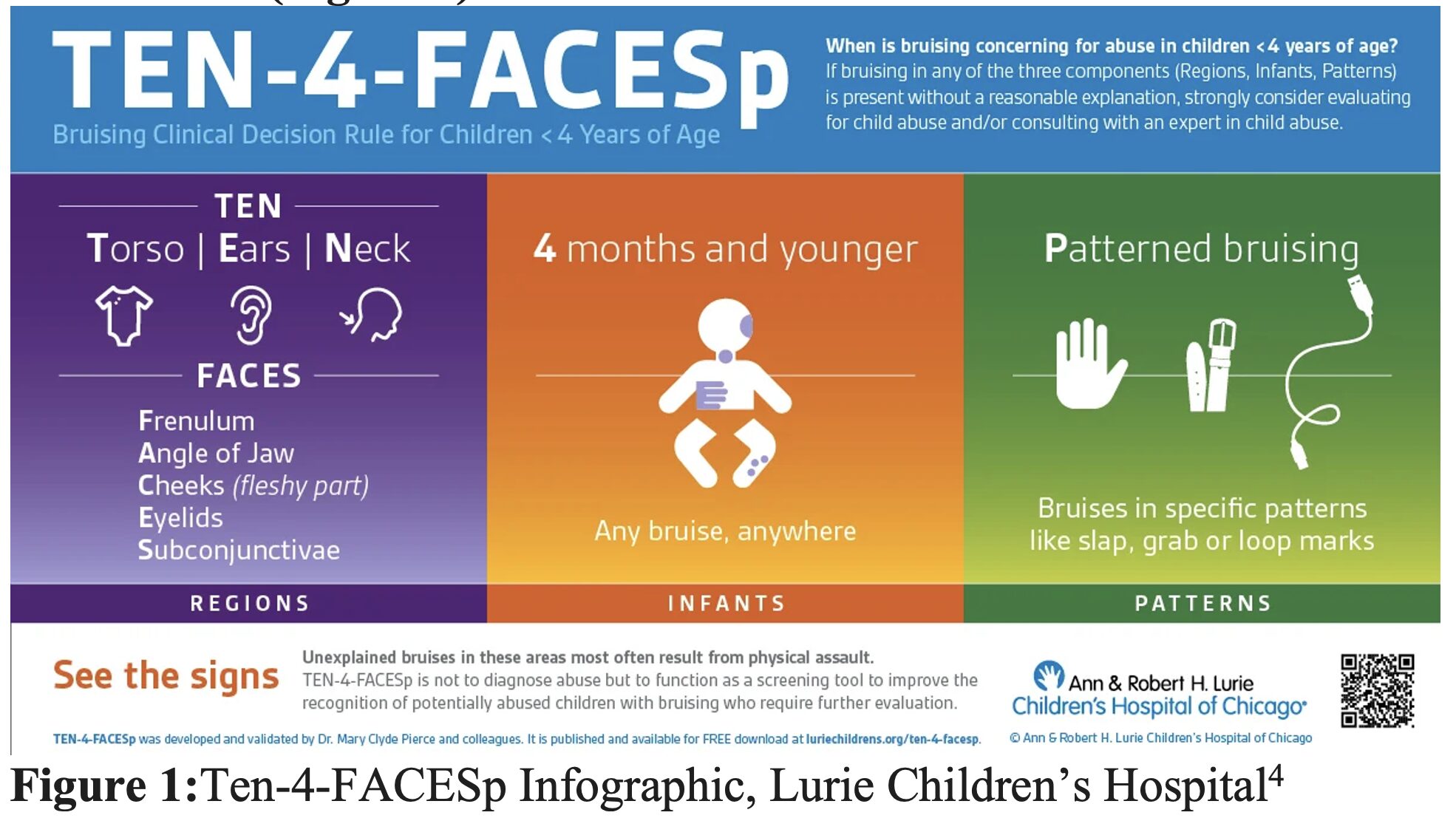

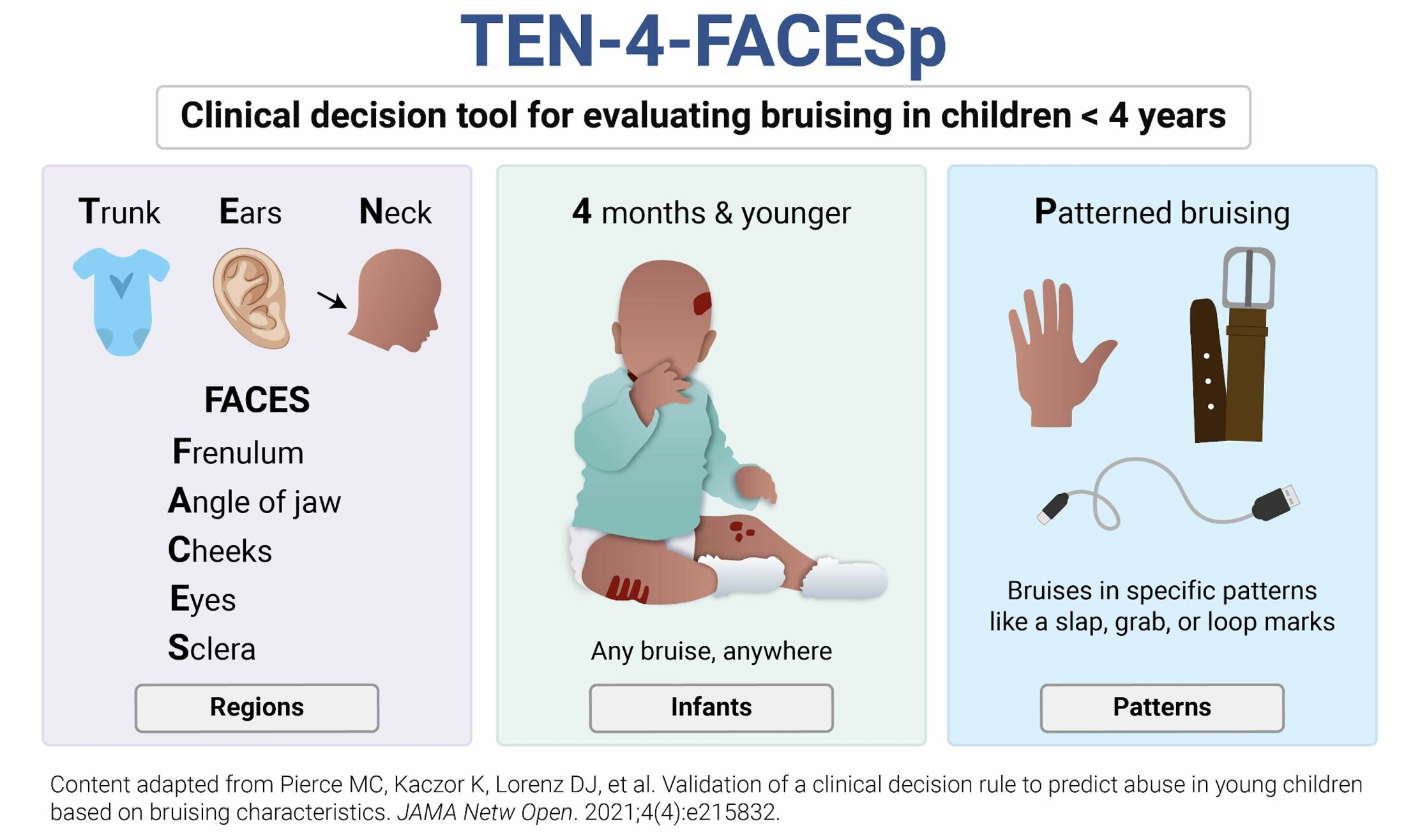

- Consider Ten-4-FACESp for bruising in children <4 years of age concerning for NAT (Figure 1)

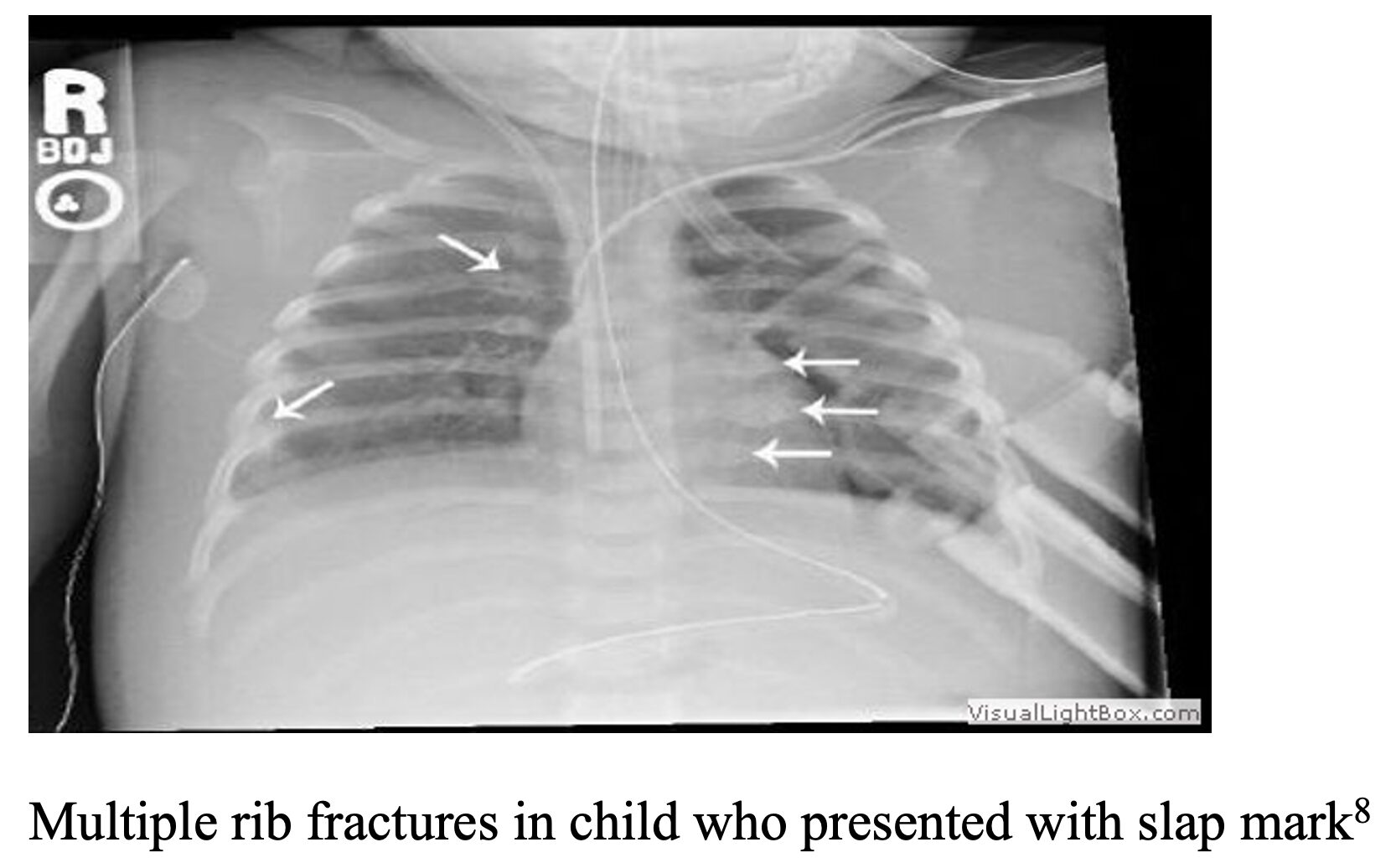

Fractures

- Only 1.5% of fractures requiring admission presenting to ED are from NAT5 so consider patterns of fracture and age of patient (most significant predictive factor for identifying fracture from NAT, as 69% of fractures related to NAT occurred in patients <1 year).

- Most common fractures associated with NAT: multiple fractures, especially at different stages of healing,mandible6, humerus7, ribs, femur8 (transphyseal distal 13x more likely to be NAT versus supracondylar), tib/fib, clavicle.

- 65% of rib fractures in pediatric trauma patients from NAT.

- Mimics/Differential Diagnosis: Rickets, Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), fractures during delivery, osteopathy of prematurity, Hyper-IgE syndrome, Caffey Disease.

Burns

- Immersion burns, look for burns on buttocks and extremities (gloves and stocking)

- Cigarette burns (blistering circular burn).

- Consider tools like the BuRN-Tool to screen a burn for NAT (Figure 2).

- Mimics/Differential Diagnosis: SJS, Staph scalded skin syndrome, contact dermatitis.

Abusive Head Trauma (AHT)

- Highest fatality rate from NAT (25%) due to increase in risk of intracranial hemorrhage, hypoxia-ischemia.

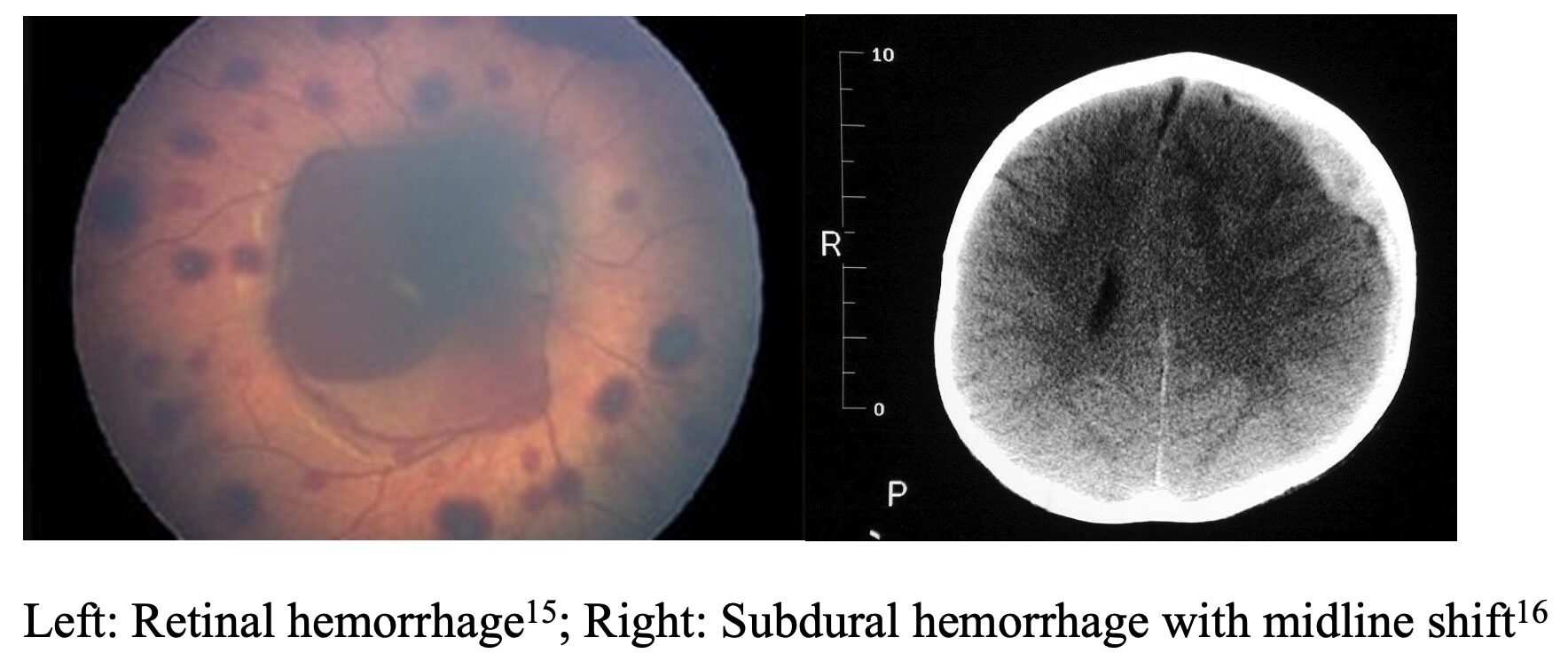

- Formerly known as “Shaken Baby Syndrome” – shearing forces lead to retinal hemorrhage/intracranial hemorrhage.

- Retinal hemorrhages have been deemed in litigation to be from birth trauma or CPR, but can be differentiated by presence of blood in macula (traumatic retinoschisis) present in NAT.11

- PECARN guidelines are not validated in cases where NAT is suspected because PECARN relies on accurate history.12

Mimics/Differential Diagnosis: Subdural hemorrhage from Vitamin K deficiency, coagulopathies, vasculopathies (Ehler’s Danlos, Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI)), AV malformations, biliary atresia (associated with intracranial hemorrhage)12, benign enlargement of subarachnoid space during infancy.13

- THOROUGH history and undressed physical exam (emphasis on skin exam, developmental history, family history for bleeding disorders, identify discrepancies in story).

- Skeletal Survey

- Obtain in children <2, children 2-5 with suspicious fracture and child unable to communicate/perform full neuro exam (intellectually disabled).

- Complete Skeletal Survey: AP humerus, AP forearms, PA hands, AP femurs, AP lower legs, PA/AP feet, AP/lateral thorax including clavicles, AP pelvis, lateral lumbosacral spine, AP and lateral cervical spine, frontal//lateral of skull. Consider oblique views of the ribs, as well.

- Includes at least 21 individual X-rays to be adequate.17 NO Babygrams

- CT Head wo Contrast if concerned for ICH

- MRI Head/C-Spine if CT head findings equivocal/concerning.18

- CT Abdomen/Pelvis wo Contrast if concern for abdominal trauma.

- Dilated fundoscopic exam/ophthalmology consult for patient < 12 month with intracranial hemorrhage.

- Labs: CBC with Diff/PT/PTT/LFTs/Lipase/UA.

- Social: Social work, Child Protective Services, child abuse pediatrics team (if your institution has one).

- Additional Tests: laboratory assessment for bone health (Vit D level, iPTH, Ca, Mg, Phos, alk phos), coagulopathy workup.

- CPS consultation, SW consultation. Determine need for sitter based on conversations with SW/CPS.

- Consult child abuse specialist. If not available in local institution, consider if transfer is necessary for in-person evaluation by child abuse expert or for higher level of care.

Disposition

- Admit for continued observation, work-up, safety planning, placement if new guardian required. Collaborate with your state’s Child Protective Services (CPS) and child abuse specialist.

- Disposition usually dependent on CPS in conjunction with social worker.

- Ensure comprehensive follow-up care is arranged before discharge.

- Discharge education to parents, support services (i.e. chaplaincy, local wellness resources).

- Avoid judgment and use trauma-informed, culturally sensitive care.

- Document communication, decisions, medical thought process meticulously and thoroughly. If taking pictures, take clear photos before dressing any injuries.

Pearls

- Consider any bruise in child under 4 months requires an occult injury work-up.

- If NAT is on differential, PECARN guidelines for head CT does NOT apply (low threshold for getting head imaging).

- A child that has a mimic for NAT bruising/fracture does not necessarily rule out NAT.

- Acute rib fractures are difficult to identify in an acute setting before they start having evidence of healing. Fractures require a minimum of 7 days to show evidence of healing (periosteal reaction).

Which of the following would raise concern for nonaccidental trauma?

A) A 14-month-old child with a bruise on the forehead

B) A 4-month-old infant with mirror image bruises on the jaw

C) A 4-year-old child with a bruise over the spinous process of L4

D) A 4-year-old child with mirror image bruises on the pretibial surfaces

Correct answer: B

Bruises raising concern for nonaccidental trauma can be screened from accidental injury using a clinical decision rule suggested by the mnemonic TEN-4-FACESp: bruises to the torso, ears, neck, any bruising in those ≤ 4 months of age, frenulum tear, bruising of the angle of the jaw, fleshy cheek, eyelid, or sclera, or any bruise with a pattern. This decision tool should only be used in patients < 4 years of age.

In a multicenter validation study of over 21,000 children with at least one bruise, the TEN-4-FACESp clinical decision rule suggested abuse as a cause of bruising with a high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. Mirror image bruises on the jaw of a 4-month-old infant are highly likely to be due to an abusive injury mechanism.

A toddler-aged child with a bruise on the forehead (A), a 4-year-old child with a bruise over the spinous process of L4 (C), and a 4-year-old child with bruising on the shins (D) all represent common locations for bruises due to unintentional injury.

References:

- Schermerhorn SMV, Muensterer OJ, Ignacio RC Jr. Identification and Evaluation of Non-Accidental Trauma in the Pediatric Population: A Clinical Review. Children (Basel). 2024 Mar 30;11(4):413. doi: 10.3390/children11040413. PMID: 38671630; PMCID: PMC11049109. Accessed May 16th, 2025.

- Baab, Shad Masters MD; Lawsing, James Fuller MD; Macalino, Cassandra Sarmiento MD; Springer, Jacob Hartry MD; Cline, David Martin MD. Nonaccidental Pediatric Trauma: Which Traditional Clues Predict Abuse?. Pediatric Emergency Care 39(9):p 641-645, September 2023. | DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000003012

- Hillary W. Petska, Lynn K. Sheets, Sentinel Injuries: Subtle Findings of Physical Abuse, Pediatric Clinics of North America, Volume 61, Issue 5, 2014, Pages 923-935, ISSN 0031-3955, ISBN 9780323326247

- Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Lorenz DJ, et al. Validation of a Clinical Decision Rule to Predict Abuse in Young Children Based on Bruising Characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e215832. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.583

- Zhao, Caixia MD; Starke, Matthew MD; Tompson, Jeffrey D. MD; Sabharwal, Sanjeev MD, MPH. Predictors for Nonaccidental Trauma in a Child With a Fracture—A National Inpatient Database Study. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 28(4):p e164-e171, February 15, 2020. | DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00502

- Wasicek P.J., Gebran S.G., Elegbede A., Ngaage L.M., Rasko Y., Ottochian M., Liang F., Grant M.P., Nam A.J. Differences in Facial Fracture Patterns in Pediatric Nonaccidental Trauma. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2020;31:956–959. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006294

- Crowe M., Byerly L., Mehlman C.T. Transphyseal Distal Humeral Fractures: A 13-Times-Greater Risk of Non-Accidental Trauma Compared with Supracondylar Humeral Fractures in Children Less Than 3 Years of Age. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022;104:1204–1211. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.21.01534.

- Barsness K.A., Cha E.S., Bensard D.D., Calkins C.M., Partrick D.A., Karrer F.M., Strain J.D. The Positive Predictive Value of Rib Fractures as an Indicator of Nonaccidental Trauma in Children. J. Trauma. 2003;54:1107–1110. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000068992.01030.A8

- Hollen L, Bennett V, Nuttall D, Emond AM, Kemp A. Evaluation of the efficacy and impact of a clinical prediction tool to identify maltreatment associated with children’s burns. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2021 Feb 12;5(1):e000796. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000796. PMID: 33644416; PMCID: PMC7883870.

- Verity Bennett, Linda Hollén, David Wilkins, Alan Emond, Alison Kemp, The impact of a clinical prediction tool (BuRN-Tool) for child maltreatment on social care outcomes for children attending hospital with a burn or scald injury, Burns, Volume 49, Issue 4, 2023, Pages 941-950, ISSN 0305-4179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2022.07.014.

- Narang S.K., Fingarson A., Lukefahr J., Sirotnak A.P., Flaherty C.E.G., Gavril A.R., Hoffert Gilmartin A.B., Haney S.B., Idzerda C.E.S.M., Laskey A., et al. Abusive Head Trauma in Infants and Children. Pediatrics. 2020;145:1409–1411. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0203

- Magana J.N., Kuppermann N. The PECARN TBI Rules Do Not Apply to Abusive Head Trauma. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016;24:382–384. doi: 10.1111/acem.13155

- Akiyama H, Okamura Y, Nagashima T, Yokoi A, Muraji T, Uetani Y. Intracranial hemorrhage and vitamin K deficiency associated with biliary atresia: summary of 15 cases. Pediatr Neurosurg 2006; 42:362–367

- Blangis F., Allali S., Cohen J.F., Vabres N., Adamsbaum C., Rey-Salmon C., Werner A., Refes Y., Adnot P., Gras-Le Guen C., et al. Variations in Guidelines for Diagnosis of Child Physical Abuse in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2129068. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.29068

- Shaken Baby Syndrome – American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismushttps://aapos.org/glossary/shaken-baby-syndrome

- Physical Child Abuse: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiologyhttps://emedicine.medscape.com/article/915664-overview

- Aertsen M. An Update on Imaging in Child Abuse. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2017 Nov 18;101(Suppl 1):9. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.1417. PMID: 30506027; PMCID: PMC6253022.

- Hymel KP, Jenny C, Block RW. Intracranial hemorrhage and rebleeding in suspected victims of abusive head trauma: addressing the forensic controversies. Child Maltreat 2002; 7:329–348