Authors: Nishok Victory Srivanasan, MD (EM Resident, University of Missouri-Columbia); Jailyn Avila, MD, FP-AEMUS; Jessica Pelletier, DO, MHPE (APD/Assistant Professor of EM/Attending Physician, University of Missouri-Columbia) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 70-year-old female presents to the ED with abdominal pain. She complains of having left lower quadrant pain for 2 days, gradually worsening until it was no longer controlled with over-the-counter meds. She also mentions that she has not had a bowel movement for two weeks but has been passing flatus. She has not taken her temperature but has felt feverish and chilly; she also vomited twice today (non-bilious and non-bloody). She has no appetite and has only managed sips of water in the past few days.

PMH: Type 2 diabetes on insulin

PSH: Appendectomy in childhood, hysterectomy 5 years ago

On physical exam, she appears ill and visibly uncomfortable. She has tachycardia and mild tachypnea but otherwise normal vitals on room air. Abdominal exam reveals diffuse tenderness, with maximal tenderness in the left lower quadrant as well as rebound and involuntary guarding.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Perforated viscus

Background:

- Hollow visceral perforation, primarily referring to gastrointestinal (GI) perforation, can be defined as a loss of continuity of the wall of a hollow viscera.

- This is a life-threatening complication with numerous underlying causes.

- Early recognition and treatment are crucial.

- Thorough history and physical exam followed by appropriate diagnostic modality is key to preventing complications.

- An earlier diagnosis can also sometimes allow for conservative management options.

Etiology:1

There are 4 broad etiologies of visceral perforation:

- Ischemia

- Infection/Inflammation

- Erosion

- Traumatic perforation (including iatrogenic trauma)

Ischemia

- Ischemic perforation results from compromise of the vascular supply, either directly from decreased perfusion (secondary to thrombosis or embolic events), or indirectly from a distal obstruction.

- The obstruction causes distension of the proximal bowel, resulting in increased pressure that decreases perfusion.

- The ischemia ultimately leads to full-thickness necrosis and perforation.

Infection

- Appendicitis and diverticulitis are the most common infections that result in perforation, caused by obstruction of a blind-ending structure (usually by fecal material), creating an ideal environment for bacterial growth.

- Inflammation is most commonly associated with conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Erosion

- Refers to the local invasion of the visceral wall.

- Potential causes:

- Erosive esophagitis.

- Peptic ulcer disease.

- Tumor (most commonly adenocarcinoma).

- Ingestion of caustic substances – acids cause coagulative necrosis, with a lower risk of perforation, while alkalis cause liquefactive necrosis and have a higher risk of perforation.2

Traumatic1

- Includes:

- Blunt and penetrating trauma.

- Boerhaave’s syndrome (i.e., esophageal rupture) can also be considered a traumatic perforation.

- Iatrogenic trauma from instrumentation.

- Blunt and penetrating trauma.

Epidemiology:

- Visceral perforation generally refers to a disruption of the wall of hollow viscera, i.e., the alimentary canal.

- Can occur anywhere from esophagus to rectum.

Gastric/Duodenal Perforation

- Potential causes:

- Peptic ulcer disease progressing to perforation used to be more common; the incidence has decreased with the advent of H2-receptor blockers and PPIs.1

- Instrumentation = more likely cause with the increasing use of esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs).3,4

- Traumatic perforations from nasogastric tubes5,6 and barotrauma from gastric ventilation (due to prolonged non-invasive ventilation or esophageal intubation).7–9

Esophageal Perforation

- Relatively rare hollow viscus injury.

- Most commonly iatrogenic (>50% of cases); 30% are spontaneous.

- Mortality rate ~20%; high morbidity and low quality of life plaguing survivors.1,2

- Diagnostic limitations are a main contributor to the high mortality; a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis will often miss esophageal perforation.

- Gold standard is either:

- Upper GI fluoroscopy, OR

- CT esophagram.

- Operative repair is challenging, due to:2

- Difficulty of accessing the esophagus.

- Unusual blood supply

- Lack of a strong serosal layer

- Endoscopic stenting is a treatment option for early perforations with minimal leak or as a bridge to operative repair.1

- Can be an option in unstable or coagulopathic patients.

Small Bowel Perforation

- Uncommon form of visceral perforation – 0.4% of acute abdomens.10

- Underlying cause differs by location:

- Low-resource countries: most commonly caused by infections, such as typhoid and tuberculosis (TB).

- Bowel obstruction followed by perforation can occur in the setting of parasite infections, like 11

- High-resource countries: small bowel obstruction and malignancy

- Low-resource countries: most commonly caused by infections, such as typhoid and tuberculosis (TB).

- Trauma, ischemia, and iatrogenic injury are other common causes.

- Pneumoperitoneum is only seen on imaging in 50% of small bowel perforations.1

Colorectal Perforation

- Major causes:12

- Inflammatory or infectious colitis.

- Malignancy.

- Trauma, ischemia, and iatrogenic.

- Management requires diversion of the fecal stream – a temporary diverting colostomy or ileostomy can allow for stronger healing of the anastomotic site.13

Non-Alimentary Visceral Perforations

- Tracheal/bronchial disruption from:14

- Mechanical ventilation.

- Penetrating trauma.

- Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Vaginal or uterine disruption (typically iatrogenic).

- Bladder rupture/perforation due to trauma, outflow obstruction, malignancy, or instrumentation is also possible.15

Atypical Causes of Visceral Perforation

- Blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) – ~6% of patients presenting with BAT will have a perforated viscus.13

- Toxic ingestions.16

Causes of Pneumoperitoneum Without Visceral Perforation

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.17

- Chronic peritoneal dialysis.

- Rapid decompression after diving.14

Clinical Presentation:1

- Severe abdominal pain is almost always the presenting complaint.

- Usually severe, sudden onset.

- Most patients will recall similar, but less severe abdominal pain prior, due to the underlying cause of the perforation.

- Associated symptoms:

- Fever.

- General malaise.

- Nausea/vomiting

- Patients who may not have classic findings:18

- Debilitated/frail.

- Elderly.

- Immunocompromised.

- Impaired pain response (neuropathy, paraplegia/quadriplegia).

- Physical examination findings:

- Vital sign abnormalities: fever, tachycardia, hypotension → septic

- Early in the course: focal tenderness.

- Later in the course: peritonitis with diffuse tenderness, involuntary guarding, rigidity.

- May hold themselves still;

- Movement of their extremities or bumping the stretcher can cause excruciating pain.19,20

- Atypical presentations: necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) of the groin or thighs without clear inciting cause can be caused by perforated viscus.21,22

Evaluation and Diagnosis:

- Labs:1

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP).

- Lactic acid.

- Lipase.

- Type and screen and coagulation studies in anticipation of surgical or interventional radiology (IR) intervention.

- Urinalysis.

- Urine pregnancy.

Chest X-Ray (CXR):

- Advantages of upright CXR:

- Can be done at the bedside for the unstable patient.

- Quick/convenient.

- Immediately available for review.

- Presence of pneumoperitoneum is diagnostic for a perforated viscus in 85-90% of cases.23,24

- Limitations:

- Variable sensitivity:

- Only 50-70% of hollow visceral perforations present with the characteristic ‘air under the diaphragm’ on an upright CXR, dropping as low as 20% in some studies.23,24

- Diagnostic utility is significantly limited by technique/positioning.

- Does not indicate the location of the perforation.23

- Variable sensitivity:

Figure 1. Free air under the right hemidiaphragm on upright CXR, caused by bowel perforation. Source: Kulkarni R, Bowel perforation – subdiaphragmatic free gas. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 09 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-21444

- Underused modality in the workup of visceral perforation.

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) revealing intra-abdominal free air or echogenic (‘dirty’) free fluid can sometimes save hours of waiting.

- Especially applicable in limited-resource settings.

- Can allow for quick evaluation of other common causes of abdominal pain (examples: cholecystitis and aortic aneurysms).

- Typical findings:12,25–28

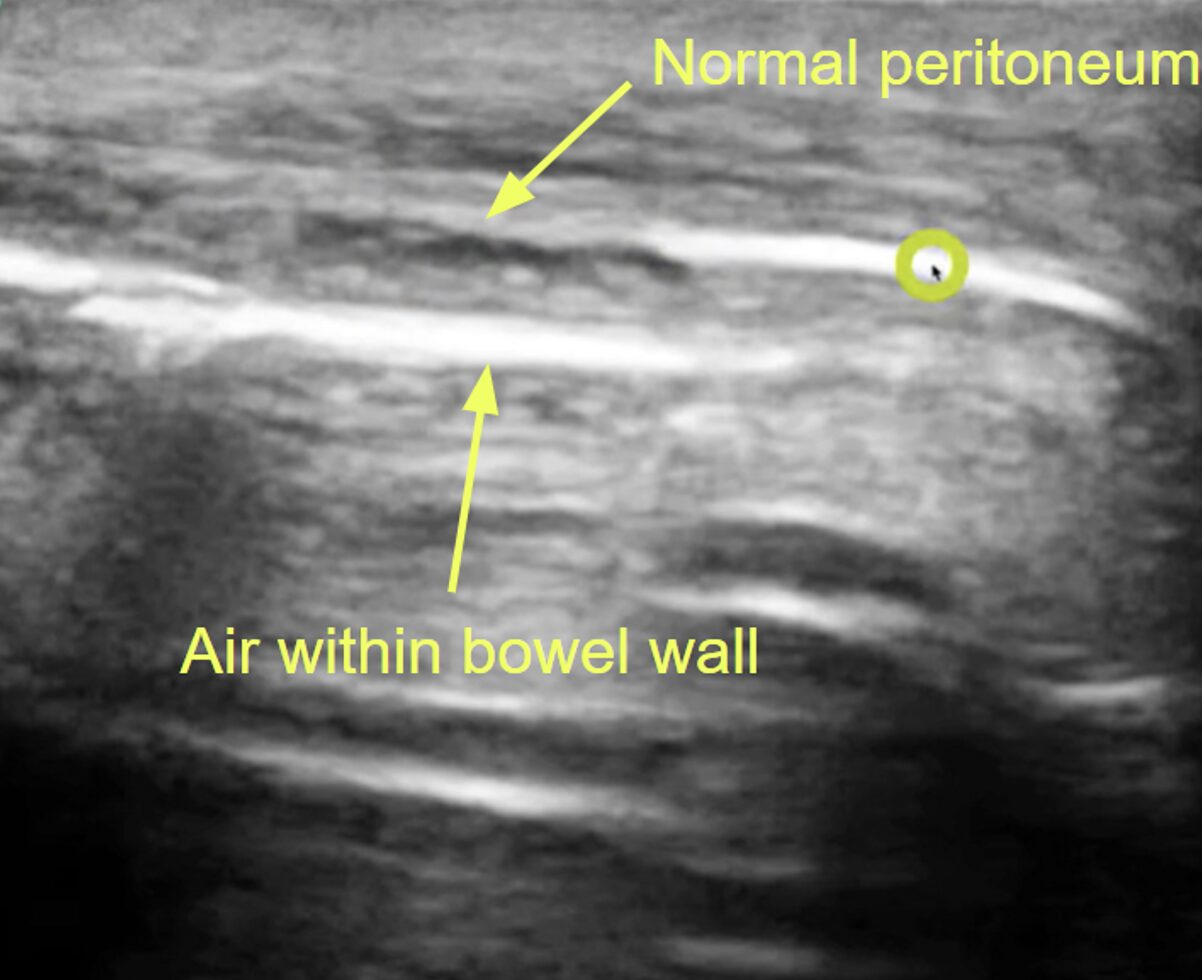

- Enhanced peritoneal stripe sign (Figures 2-4).

- Caused by scattering of ultrasound waves at the junction of soft tissue and air, creating a high-amplitude linear echo (the “peritoneal stripe) and a ‘comet-tail’ of reverberation echoes posteriorly.

- Free air (Figure 5).

- Most specific finding.

- Appears as highly echogenic foci with posterior reverberation artifacts.

- Best visualized in the right paramedian epigastric area with the patient supine.

- May be seen ventral to the liver, around the right kidney, or adjacent to the great abdominal vessels.

- Echogenic or “dirty” free fluid.

- In jejuno-ileal and gastroduodenal perforations, intraperitoneal free fluid may be the only sonographic sign in the absence of detectable free air.

- Direct visualization of an intestinal wall defect.

- More commonly seen in pediatric populations.

- May see communication between intraluminal contents and echogenic ascites, with passage of tiny echogenic gas bubbles from the bowel lumen into the peritoneal cavity.

- Reduced peristalsis.

- Ring-down or reverberation artifact.

- Shifting shadows.

- Retroperitoneal perforations may present with:27

- Air dorsal to the gallbladder.

- Increased echogenicity around the right kidney.

- “Vanishing” vessels due to air ventral to major abdominal vessels.

- Limitations:

- Enhanced peritoneal stripe sign (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2. Normal peritoneal stripe (green circle) in the absence of pneumoperitoneum on POCUS. Note the B-lines emanating from inside of the bowel wall in the lower half of the image, indicating air contained within the bowel. Source: Avila, Jailyn. Five Min Sono – Pneumoperitoneum. CORE Ultrasound, 5 Minute Sono, https://coreultrasound.com/pneumoperitoneum/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2025.

Figure 3. Enhanced peritoneal stripe on the right half of this image (green circle) indicating free air within the peritoneum. Source: Avila, Jailyn. Five Min Sono – Pneumoperitoneum. CORE Ultrasound, 5 Minute Sono, https://coreultrasound.com/pneumoperitoneum/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2025.

Figure 4. Another example of an enhanced peritoneal stripe, this time on the left half of the image (green circle). Note the a-lines and reverberation artifact inferior to the enhanced peritoneal stripe. Source: Avila, Jailyn. Five Min Sono – Pneumoperitoneum. CORE Ultrasound, 5 Minute Sono, https://coreultrasound.com/pneumoperitoneum/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2025.

Figure 5. Air bubbles adjacent to the peritoneal lining, suggestive of pneumoperitoneum (green circle). Source: Avila, Jailyn. Five Min Sono – Pneumoperitoneum. CORE Ultrasound, 5 Minute Sono, https://coreultrasound.com/pneumoperitoneum/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2025.

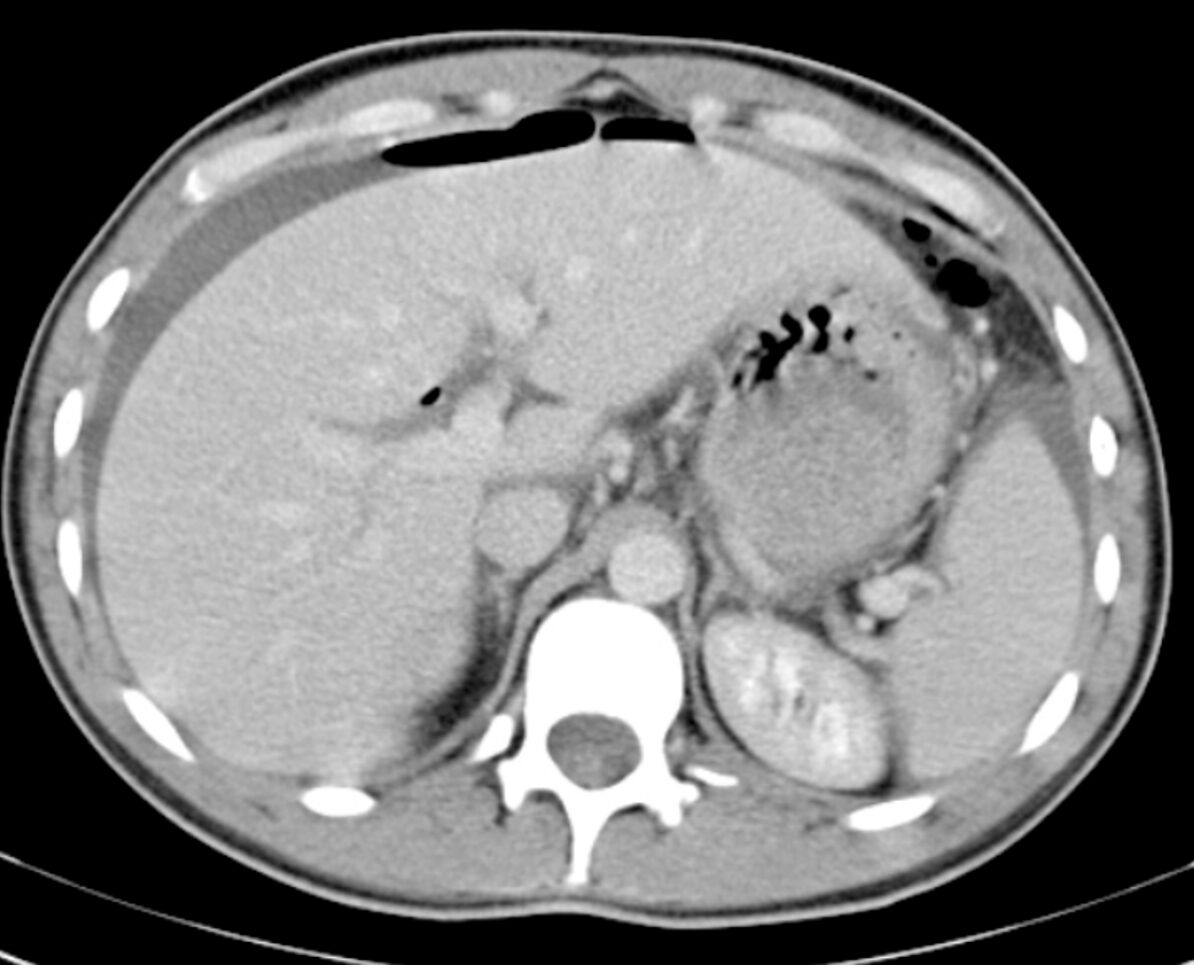

Computed Tomography (CT):

- Advantages:12,31

- Can detect even minimal free air with significant accuracy.

- Can indicate the location and size of the perforation.

- Can also diagnose other causes of acute abdomen.32

Figure 6. Pneumoperitoneum with free air extending into an umbilical hernia on axial CT abdomen/pelvis using lung window. This patient suffered a perforated viscus secondary to malignancy. Source: Di Muzio B, Pneumoperitoneum. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 09 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-19130

Figure 7. Pneumoperitoneum anterior to the liver on axial CT abdomen/pelvis. The cause of the free air was never identified for this patient. Source: Puyó Vera D, Pneumoperitoneum. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 09 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-23601

Treatment:

- These patients are critically ill and need close monitoring, as they can rapidly decompensate at any time.

- ABCs:

- Ensure that the patient is adequately protecting their airway.

- Provide supplemental oxygen or obtain a definitive airway if needed.

- Two large-bore IVs.

- Aggressive fluid resuscitation.

- If vitals remain unstable after a 30 cc/kg fluid bolus, do not hesitate to start vasopressors (usually norepinephrine).33

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated early.33,34

- Specific antibiotics depend on the site of the perforation.

- Must cover gram-negative, gram-positive, and anaerobic organisms; empiric regimens can be found in Table 1.

- The different empirical regimens do not show any significant difference in efficacy or complications, so no specific regimen is recommended.34

- When to add empiric antifungal therapy (first-line: fluconazole 12mg/kg loading dose followed by 6mg/kg daily):

- Immunocompromised patients.

- Hospital-acquired intra-abdominal infections (e.g., postoperative anastomotic leak, perforation after abdominal surgery, or worsening necrotizing pancreatitis causing perforation).29

- Early surgical consultation, often before the diagnosis is confirmed with imaging.

- Unstable patients should not be sent to the CT scanner; diagnostic laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy is usually the better choice.

- Surgical management involves resection or repair of the perforated segment and removal of the gross contamination with large-volume washout.29

Table 1. Empiric IV Antibiotic Regimens for the Treatment of GI Perforation.11

| Ceftriaxone + Metronidazole | Imipenem-Cilastatin | Meropenem | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |

| Dose | 1-2g once daily + 500mg every 8 hours | 500mg every 6 hours | 1g every 8 hours | 3.375-4.5g every 6 hours |

| Duration | 7-14 days | 7-14 days | 7-14 days | 7-14 days |

Prognosis:

- Strongly influenced by:

- Scoring systems can stratify patients, with higher scores indicating worse prognosis:

- APACHE II (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/1868/apache-ii-score).

- Mannheim Peritonitis Index (https://mobile.fpnotebook.com/Surgery/Exam/MnhmPrtntsIndx.htm)

- Long-term:38

- Mortality risk remains elevated for several years after surgery.

- Outcomes are worse in patients who have:

- Malignant or infectious etiologies.

- Septic shock.

- Severe peritoneal contamination.

Pearls:

- CT is the gold standard for diagnosis, but plain radiographs and POCUS, if used appropriately, can be of great utility in unstable

- Be aware that the absence of pneumoperitoneum on chest or abdominal x-rays can be falsely reassuring.

- Stabilize and resuscitate the patient before going to the CT scanner.

- Vulnerable populations will often have a falsely reassuring clinical presentation, have a low threshold for further work-up, and early intervention.

- Surgery is your friend – get that early surgery consult. Early intervention saves lives.

- Resuscitation and antibiotics are just as important as surgery.

A 55-year-old man with a history of peptic ulcer disease presents to the ED with sudden, severe abdominal pain that began abruptly around 12 hours ago. He describes the pain as intense and constant, radiating to his shoulders. He also reports feeling nauseated but has not vomited. On examination, he has significant abdominal tenderness with guarding and rigidity. His vital signs show mild tachycardia. His X-ray is shown above. What is the most appropriate next step?

A) Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis

B) Nasogastric tube insertion

C) Observation and serial abdominal exams

D) Surgical consultation

Correct answer: D

This patient’s presentation, including the acute onset of severe abdominal pain, radiating shoulder pain, abdominal rigidity, and the presence of free air under the diaphragm on X-ray, strongly suggests perforated peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and the most appropriate next step in this scenario is surgical consultation.

Perforated PUD is a serious complication in which an ulcer creates a full-thickness hole in the stomach or duodenal wall, allowing gastric or duodenal contents to leak into the peritoneal cavity. This perforation most commonly occurs in chronic PUD, with major risk factors being chronic use of NSAIDs, Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, and excessive alcohol intake. NSAIDs inhibit protective prostaglandins in the gastric mucosa, increasing susceptibility to ulcer formation. H. pylori infection also damages the mucosal lining, promoting ulceration. Additionally, corticosteroid use and certain underlying diseases like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and chronic lung or kidney disease increase the risk.

Patients with a perforated ulcer typically present with sudden, severe abdominal pain, often described as sharp or stabbing. The pain may initially be localized to the epigastrium but often becomes diffuse and radiates to the shoulders, especially if diaphragmatic irritation from free air has occurred. This symptom is frequently accompanied by nausea and occasionally vomiting. Due to the sudden onset of pain, patients often appear ill and distressed. On physical examination, abdominal rigidity, guarding, and rebound tenderness are common, indicative of peritoneal inflammation. The abdomen is usually tender throughout, and bowel sounds may be diminished or absent due to paralytic ileus secondary to peritonitis. Signs of sepsis such as fever, tachycardia, and hypotension may also be present if the perforation has been present for a prolonged period, allowing bacterial peritonitis to develop.

Diagnosis of a perforated peptic ulcer is typically made with imaging. An upright chest or abdominal X-ray often reveals free air under the diaphragm, confirming the presence of a perforation. If the diagnosis is uncertain or if additional anatomical detail is needed, a CT scan of the abdomen can provide a more detailed view of the perforation and extent of intra-abdominal air and fluid. Laboratory tests may show leukocytosis and elevated inflammatory markers, though these findings are nonspecific. Serum amylase may be mildly elevated, especially in cases that involve gastric perforation.

Treatment of a perforated peptic ulcer is a medical emergency, requiring prompt surgical intervention. Initial management focuses on resuscitation with intravenous fluids, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Proton pump inhibitors are typically administered to decrease gastric acid production. Nasogastric (NG) tube insertion can be used for gastric decompression, reducing the risk of further leakage. Definitive treatment usually involves surgical repair of the perforation, often through a laparoscopic or open procedure. Depending on the extent of contamination and tissue damage, a Graham patch (omental patch) may be used to cover the perforation.

The prognosis of a perforated peptic ulcer depends on the timing of intervention, patient comorbidities, and the extent of peritoneal contamination. Early diagnosis and treatment lead to better outcomes, while delayed intervention increases the risk of severe peritonitis, sepsis, and mortality.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (A) is indicated if the X-ray does not reveal evidence of free air and the patient has ongoing pain and tenderness, requiring a diagnosis. Some perforations will not show on plain films, and as time progresses, the area of perforation may wall off and not show on X-ray.

NG tube (B) may be placed to decompress the stomach and manage symptoms, but it is an adjunctive measure. Definitive treatment for a perforation requires surgery, so NG tube placement would not be the primary next step.

Observation and serial abdominal exams (C) are not sufficient for a patient with a perforation. Surgical intervention is necessary, as observation would only delay necessary treatment, increasing the risk of complications.

Further Reading:

Further FOAMed:

- https://www.emdocs.net/bowel-perforation-ed-presentations-evaluation-and-management/

- https://www.emdocs.net/pneumoperitoneum-ed-presentation-evaluation-and-management/

- https://www.emdocs.net/em3am-viscous-perforation/

- https://www.emdocs.net/the-em-educator-series-abdominal-pain-that-wont-go-away-gastric-bowel-perforation/

- https://www.emdocs.net/medical-malpractice-insights-bowel-perforation-due-to-stercoral-ulcer/

- https://www.emdocs.net/emdocs-revamp-esophageal-perforation/

- https://www.emdocs.net/emdocs-podcast-episode-62-esophageal-perforation-rupture/

- https://www.emdocs.net/esophageal-perforation-pearls-and-pitfalls-for-the-resuscitation-room/

References:

- Tanner TN, Hall BR, Oran J. Pneumoperitoneum. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98(5):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2018.06.004

- Søreide J, Viste A. Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19(1):66. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-66

- Di Mitri R, Amata M, Mocciaro F, et al. Acute iatrogenic gastric perforation during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for malignant biliary obstruction: intraoperative over-the-scope clip closure and EUS-guided biliary drainage with lumen-apposing metal stent. Endoscopy. 2023;55(S 01):E60-E61. doi:10.1055/a-1930-5996

- Oshiro M, Kanda H, Oshiro A, et al. Conservative management for iatrogenic gastric perforation by transesophageal echocardiography. JA Clin Rep. 2018;4(1):52. doi:10.1186/s40981-018-0189-7

- Albendary M, Mohamedahmed AYY, George A. Delayed Adult Gastric Perforation Following Insertion of a Feeding Nasogastric Tube. Cureus. Published online November 9, 2021. doi:10.7759/cureus.19411

- Wallbridge T, Eddula M, Vadukul P, Bleasdale J. Delayed gastric perforation following nasogastric tube insertion: the pitfalls of radiographic confirmation. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(11):e244824. doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-244824

- Lazovic B, Dmitrovic R, Simonovic I, Esquonas A, Mina B, Zack S. Unusual complications of non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) and high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC): A systematic review. Tuberk Toraks. 2022;70(2):197-202. doi:10.5578/tt.20229810

- Vemuru SR, Stettler GR, Betz ME, Ferrigno L. Gastric Perforation Secondary to Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation Following Opioid Overdose. Am Surg. 2022;88(6):1354-1356. doi:10.1177/0003134820945197

- Butterfield M, Peredy T. On-Scene Rescue Breathing Resulting in Gastric Perforation and Massive Pneumoperitoneum. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2017;32(6):682-683. doi:10.1017/S1049023X17006653

- Hines J, Rosenblat J, Duncan DR, Friedman B, Katz DS. Perforation of the mesenteric small bowel: etiologies and CT findings. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20(2):155-161. doi:10.1007/s10140-012-1095-3

- Brown RF, Lopez K, Smith CB, Charles A. Diverticulitis: A Review. JAMA. 2025;334(13):1180. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.10234

- Gangadhar K, Kielar A, Dighe MK, et al. Multimodality approach for imaging of non-traumatic acute abdominal emergencies. Abdom Radiol. 2016;41(1):136-148. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0586-6

- Otani K, Kawai K, Hata K, et al. Colon cancer with perforation. Surg Today. 2019;49(1):15-20. doi:10.1007/s00595-018-1661-8

- Oh ST, Kim W, Jeon HM, et al. Massive Pneumoperitoneum After Scuba Diving. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18(2):281. doi:10.3346/jkms.2003.18.2.281

- Parvez M D, Supreet K, Ajay S, Subodh K. Intraperitoneal Urinary Bladder Rupture as a Cause of Pneumoperitoneum. Am Surg. 2023;89(5):2079-2081. doi:10.1177/00031348211025765

- Nordal T, Burcharth J, Cordtz AC, Storm N, Jensen TK. Cholestyramine crystal deposits as a possible cause of small bowel perforation. Ugeskr Læg. Published online June 17, 2024:1-5. doi:10.61409/V02240109

- Singh S, Khardori NM. Intra-abdominal and Pelvic Emergencies. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96(6):1171-1191. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.09.002

- Almuebid AM, Alsadah ZY, Al Qattan H, Al Mulhim AA, Alfaraj D. Atypical Presentation of Perforated Viscus as Biliary Colic. Cureus. Published online January 5, 2021. doi:10.7759/cureus.12513

- Yew KS, George MK, Allred HB. Acute Abdominal Pain in Adults: Evaluation and Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(6):585-596.

- Golledge J, Toms AP, Franklin IJ, Scriven MW, Galland RB. Assessment of peritonism in appendicitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78(1):11-14.

- Connor MJ, Thomson AR, Grange S, Agarwal T. Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Thigh and Calf: A Reminder to Exclude a Perforated Intra-Abdominal Viscus: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2016;6(2):e44. doi:10.2106/JBJS.CC.15.00217

- Hua J, Yao L, He ZG, Xu B, Song ZS. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by perforated appendicitis: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(3):3334-3338.

- Hajibandeh S, Shah J, Hajibandeh S, et al. Erect chest x-ray is inadequately diagnostic and falsely reassuring in assessment of abdominal visceral perforation. Radiography. 2022;28(1):249-250. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2021.10.014

- Bansal J, Jenaw RK, Rao J, Kankaria J, Agrawal NN. Effectiveness of plain radiography in diagnosing hollow viscus perforation: study of 1,723 patients of perforation peritonitis. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19(2):115-119. doi:10.1007/s10140-011-1007-y

- Shokoohi H, Boniface KS, Abell BM, Pourmand A, Salimian M. Ultrasound and Perforated Viscus; Dirty Fluid, Dirty Shadows, and Peritoneal Enhancement.

- Grechenig W, Peicha G, Clement HG, Grechenig M. Detection of pneumoperitoneum by ultrasound examination: an experimental and clinical study. Injury. 1999;30(3):173-178. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(98)00248-4

- Nürnberg D, Mauch M, Spengler J, Holle A, Pannwitz H, Seitz K. Das sonografische Bild des Pneumoretroperitoneums als Folge einer retroperitonealen Perforation. Ultraschall Med – Eur J Ultrasound. 2007;28(06):612-621. doi:10.1055/s-2007-963216

- Pinto A, Miele V, Laura Schillirò M, et al. Spectrum of Signs of Pneumoperitoneum. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2016;37(1):3-9. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2015.10.008

- Sartelli M, Chichom-Mefire A, Labricciosa FM, et al. The management of intra-abdominal infections from a global perspective: 2017 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12(1):29. doi:10.1186/s13017-017-0141-6

- Mehmetoğlu F. Analysis of the use of upright abdominal radiography for evaluating intestinal perforations in handlebar traumas: Three case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(23):e15889. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000015889

- Hsia CC, Wang CY, Huang JF, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Computed Tomography for the Prediction of the Need for Laparotomy for Traumatic Hollow Viscus Injury: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2021;11(12):1269. doi:10.3390/jpm11121269

- Paolantonio P, Rengo M, Ferrari R, Laghi A. Multidetector CT in emergency radiology: acute and generalized non-traumatic abdominal pain. Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1061):20150859. doi:10.1259/bjr.20150859

- Nascimbeni R, Amato A, Cirocchi R, et al. Management of perforated diverticulitis with generalized peritonitis. A multidisciplinary review and position paper. Tech Coloproctology. 2021;25(2):153-165. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02346-y

- Wong PF, Gilliam AD, Kumar S, Shenfine J, O’Dair GN, Leaper DJ. Antibiotic regimens for secondary peritonitis of gastrointestinal origin in adults. Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2012(5). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004539.pub2

- Mingoli A, La Torre M, Brachini G, et al. Hollow viscus injuries: predictors of outcome and role of diagnostic delay. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;Volume 13:1069-1076. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S136125

- Møller MH, Adamsen S, Thomsen RW, Møller AM. Preoperative prognostic factors for mortality in peptic ulcer perforation: a systematic review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(7-8):785-805. doi:10.3109/00365521003783320

- Al-Qurayshi Z, Srivastav S, Kandil E. Postoperative outcomes in patients with perforated bowel: early versus late intervention. J Surg Res. 2016;203(1):75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.03.023

- Maurer LR, Martin ND. Sepsis management of the acute care surgery patient: What you need to know. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2025;98(4):533-540. doi:10.1097/ta.0000000000004467