Authors: Anthony DeVivo, DO (EM Resident Physician, Mount Sinai St. Luke-West) and Jenny Beck-Esmay, MD (EM Attending Physician, Co-director – Medical Student Clerkship, Mount Sinai St. Luke-West) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 22 y/o female presents to the ED via EMS for several hours of progressively worsening chest pain and shortness of breath. As per EMS, patient was in respiratory distress on scene, with poor air entry in the setting of a history of asthma and was given multiple albuterol nebulizer treatments, solumedrol 125mg IV, and magnesium 2gm IV with minimal improvement. She is brought immediately to the resuscitation room, IV access is confirmed, and is placed on a cardiac monitor while receiving continuous nebulizer treatments via non-rebreather mask. Initial history is limited due to dyspnea. The mother of the patient also arrived with EMS and affirms the patient has a history of asthma, depression, and body dysmorphic disorder and has been dieting heavily over the past several weeks.

VS include BP 82/46, HR 130, RR 32, Sat 90% on NRB, Temp 101

The patient is ill appearing and in moderate respiratory distress. She is moving air to her bilateral lung bases with no clear wheezing, rales, or rhonchi. There are no signs of trauma to the anterior chest wall, but there is possible crepitus. No low extremity edema is noted.

The charge nurse walks into the resuscitation room while you are evaluating this patient and asks if you would like Respiratory called for BiPAP. Is this patient a good candidate for BiPAP? Are there other concerns besides an acute asthma exacerbation or infectious process? Could BiPAP worsen this patient’s condition?

Introduction

Esophageal perforation is a rare but frequently life-threatening condition that requires consideration in the appropriate clinical context in order to diagnose upon initial presentation.1-2 While the etiologies of this pathology are vast, by far most common is an iatrogenic cause, often secondary to endoscopic procedures. However, iatrogenic esophageal perforation is frequently recognized during the procedure, and so may not be the most common etiology presenting to the ED.4-5 The lack of serosal layer makes the esophagus more prone to rupture, compared with the rest of the GI tract.1,2 Additional etiologies of esophageal perforation include trauma, foreign body or caustic ingestion, invasive neoplasm, infection, and spontaneous perforation.1-2 Spontaneous perforation, also known as Boerhaave Syndrome, is the result of a rapid increase in intraesophageal pressure in conjunction with opposing negative intrathoracic pressure, as occurs with deep inspirations between forceful vomiting. Regardless of the etiology, this diagnosis often presents in a vague manner and possesses a high rate of mortality which requires early recognition and early intervention.

The high mortality of esophageal perforation is due to the extravasation of gastric contents, digestive enzymes, and bacteria into the mediastinal space after the tear occurs. This leads to the development of mediastinitis, formation of empyemas, systemic infection, and frequently, death. In addition to mediastinal exposure, the parietal pleura of the lung may also rupture simultaneously leading to a pneumothorax.1-3 The high mortality of this condition’s pathophysiology is confounded by the frequent delay in diagnosis due to nonspecific presentations and the baseline low index of suspicion held by diagnosticians. Presentations may range from chest pain and dyspnea to distributive shock secondary to systemic bacterial infection.1,2,4,5 The remainder of this article will focus on early recognition of esophageal perforation upon initial presentation, early management, and expedient disposition.

Resuscitation Bay History and Physical Exam

Patients with esophageal perforation frequently present with nondescript complaints such as chest pain, dyspnea, or simply with respiratory distress. Due to the varied presentations of this pathology, a brief, focused history is vital to successful early diagnosis, treatment, and appropriate disposition.

History Pearls:

- Obtain key pieces of history that may increase your clinical suspicion for esophageal perforation:

- Most common presenting symptom is chest pain.

- The classic presentation of chest pain, vomiting, and subcutaneous air, known as Mackler’s triad, is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis but should highly raise clinical suspicion.

- Patients who have recently experienced symptoms of forceful vomiting or have a history of bulimia are at risk for developing spontaneous esophageal rupture. In less common scenarios, heavy weight lifting may also precipitate Boerhaave syndrome.

- Past history of esophageal cancer or infection can cause weakening in the muscular layers of the esophagus, putting patients at a higher risk for rupture. In particular, a history of HIV places patients at a higher risk for multiple esophageal infections.1-2

- History of recent endoscopic procedure.

- Penetrating trauma to the neck or upper thoracic region.

- History of potential foreign body or caustic ingestion should place esophageal rupture on the differential in the appropriate clinical setting. A particularly high index of suspicion should be kept in the pediatric population.

- In terms of ingestants, alkali substances are particularly concerning due to their tendency to cause rapid transmural perforation via liquefactive necrosis.

- As always, use every modality of history taking at your disposal from the patient, to family and friends, to your electronic medical record.

History Pitfalls:

- Nondescript symptoms such as chest pain and shortness of breath present to the ED countless times per day. Particularly in the setting of the resuscitation room, with limited history available, it is easy to think first of the more common etiologies of chest pain or respiratory distress.

- Beware of clinical tunnel vision and anchoring on the more common etiologies of chest pain and respiratory distress.

- If the pieces to the clinical puzzle aren’t aligning the way you want them to, take a step back and reevaluate the situation.

- Patients with esophageal rupture will not always necessarily present with severe symptoms or in extremis. In some situations, the initial severe chest pain may have occurred with rupture and initial extravasation of contents but then sealed off. In these settings, patients may present with normal vital signs and well appearing, but are at high risk for decompensation and septic shock due to mediastinitis.

Physical Exam Pearls:

- Patients presenting with esophageal perforations will generally be uncomfortable in appearance, possibly septic or in extremis due to their pathology. This leads to the need for a very focused physical exam in conjunction with team-based resuscitation.

- Vitals signs will be deranged in most patients presenting with esophageal rupture. Tachycardia and tachypnea will likely be present due to discomfort. However, fever in the setting of possible esophageal rupture is concerning for mediastinitis progressing to sepsis.

- Assess for crepitus throughout the neck and anterior chest wall indicative of subcutaneous air.

- Unilateral diminished breath sounds may indicate pneumothorax which may occur in conjunction to esophageal rupture.

Physical Exam Pitfalls:

- Physical exam findings indicative of septic shock or tension pneumothorax may lead to anchoring on a singular diagnosis, while in fact may both be subsequent to esophageal rupture.

- Mediastinal emphysema requires significant time to develop, and its absence does not rule out esophageal perforation.

Resuscitation

Initial assessment of patients presenting with esophageal rupture will frequently occur in a resuscitation bay setting due to abnormal vitals and respiratory extremis, such as the patient described in the clinical scenario above. As with all resuscitations or clinically ill appearing patients, assessment begins with ABCs.

Airway

Patients with esophageal perforation may require a definitive airway at some point during their ED evaluation. This may be due respiratory compromise from initial perforation, worsening altered mental status from dyspnea and septic shock, or even just for airway protection if the patient is going to require transport for definitive care and there is concern for decompensation. However, the diagnosis may be unclear during initial presentation, as in the case presented above. A patient presenting in respiratory distress with a history of asthma, COPD, or CHF might be considered for a trial of BiPAP to prevent intubation.3 However, initiation of BiPAP on a patient with an esophageal perforation may lead to positive pressure being forced into the mediastinum through the tear. This could significantly worsen the patient’s clinical condition, and should thus be avoided until the situation is further clarified. In addition, these patients should be considered a difficult airway and intubated with whatever means will provide the highest likelihood of first pass success, as incidental esophageal intubation could significantly worsen the patient’s condition.1-3

Breathing

A wide differential should be considered when assessing a patient with chest pain in respiratory distress. Patients with esophageal rupture may also have sustained a pneumothorax during the initial force of perforation or develop of hydropneumothorax due to expulsion of gastric contents into the thoracic cavity. These confounding pathologies may impair breathing and worsen the patient’s clinical condition. While a pneumothorax is traditionally diagnosed either clinically if tension physiology is present or by chest x-ray, the advent of point of care ultrasound has allowed ED physicians a faster modality of diagnosis. A point of care ultrasound to assess for lung sliding can quickly and reliably diagnose pneumothorax and expedite appropriate intervention.1-3

Circulation

The development of mediastinitis from the extravasation of gastric contents and bacteria into the mediastinal space can cause rapid dissemination of bacteria into the bloodstream resulting in distributive shock and rapid cardiovascular collapse. Early recognition and intervention of septic shock with adequate fluid resuscitation, and if necessary vasopressor induction, is paramount in the resuscitation of these patients.2-3 In addition, circulation may be impaired due to a large pneumothorax or tension pneumothorax and should be addressed accordingly. The assessment of circulation during the evaluation of a patient with concern for esophageal perforation is another circumstance at which point of care ultrasound is of particular use, as both the presence of pneumothorax and volume status may be rapidly evaluated.3

- Early management

- Early broad-spectrum IV antibiotics.

- Appropriate pain control to avoid sudden increases in intraesophageal pressure.

- Antiemetic administration to avoid worsening of esophageal tear and further extravasation of GI contents into the mediastinum.

- Adequate sedation for intubated patients as agitation, dry heaving, or resistance of the ventilator may cause sudden increases in intraesophageal pressures causing worsening of the tear.3-4,9-10

Early Diagnosis

As previously discussed, the most important tool in the early diagnosis of an esophageal perforation is a high index a suspicion, as the presenting symptoms are vast and associated with a variety of other diagnosis. There are multiple imaging modalities that can support clinical suspicion of the diagnosis in the emergency department but definitive diagnosis will likely not occur in the resuscitation room.4-6

- Chest X-ray

- Mediastinal widening, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous air may be present. CXR is neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosing an esophageal perforation.

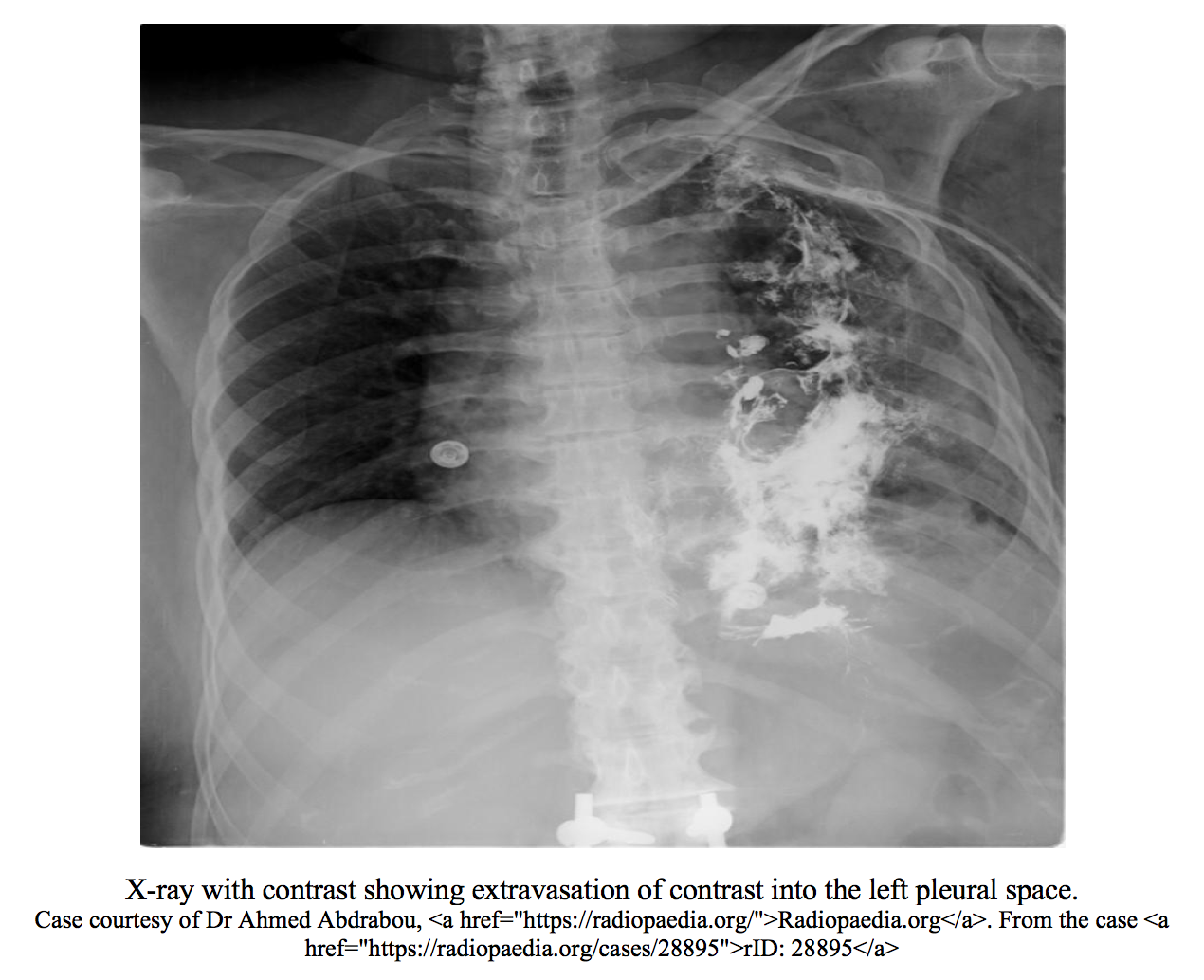

- Contrast Esophagram

- Extravasation of water-soluble contrast indicates esophageal perforation.

- Utilized in hemodynamically stable patients who can tolerate PO contrast.

- A water-soluble contrast study should first be performed due to the risk of mediastinal inflammation from barium.

- If water soluble contrast study is negative, a barium swallow study should be performed to confirm no small tears.6

- CT Scan

- Findings on CT of the chest and abdomen are diagnostic for esophageal tear.

- Utilize if patient is unstable, uncooperative, or unable to tolerate PO contrast.

- Endoscopy

- Utilization of endoscopy for the diagnosis is controversial, as instrumentation can worsen a tear.4,7

- Indicated if planned to be diagnostic as well as therapeutic.

Management and disposition

The diagnosis of esophageal perforation carries significant mortality, and thus all patients, even if nontoxic appearing upon presentation, should still be considered critically ill. These patients will require early consultation of multiple specialists and should be admitted to an ICU.1,4,9-10

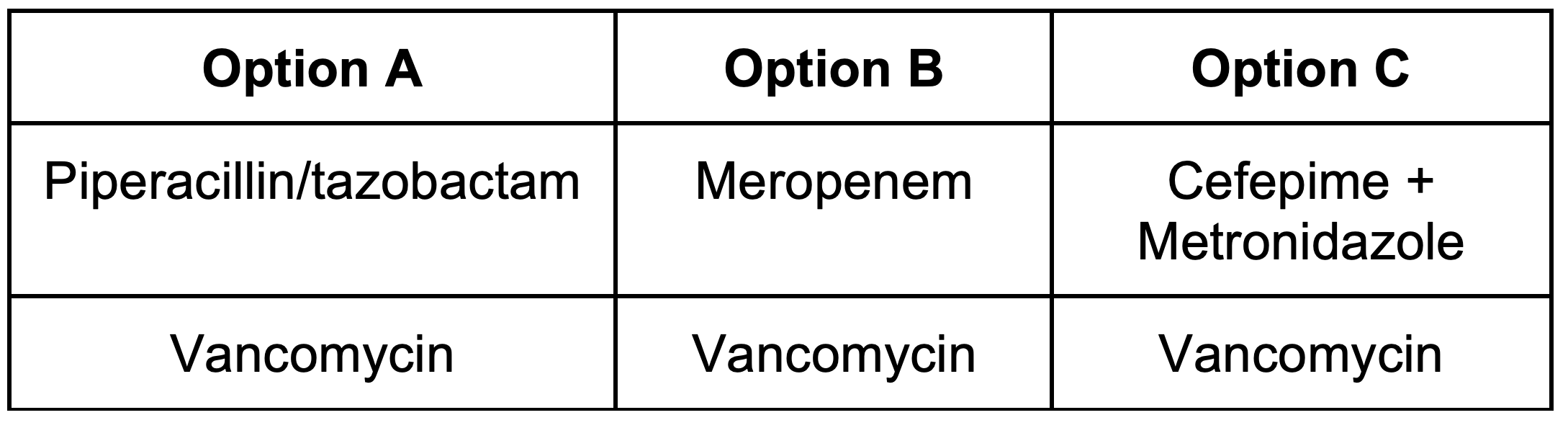

- Early broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, including anaerobic coverage due to concern for gut flora extravasating into the mediastinum. The chart below lists three options in no specific order for the antibiotic management of esophageal perforation. The first row of the antibiotic regimens cover for gram + and gram – bacteria, pseudomonas, as well as anaerobes. Both Piperacillin/tazobactam and Meropenem cover for all of the organisms previously mentioned on their own, however, Cefepime does not appropriately cover for anaerobic bacteria. Thus, if Cefepime is utilized, additional anaerobic coverage with metronidazole would be required. The second row for all three of these regimens is vancomycin in order to cover for Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus.

- If there is concern for candidal esophageal colonization, such as in patients with a history of HIV/immunocompromised states, or that are on chronic proton pump inhibitor therapy, IV antifungal therapy should also be considered with Caspofungin or Fluconazole.2,11

- Appropriate intervention for associated pathologies such as chest tube placement for pneumo or hemothorax.

- Surgical consultation for primary repair, intervention of pneumothorax, hydrothorax, empyema, or significant pneumomediastinum.12

- Gastroenterology consultation, particularly if perforation was iatrogenic, for possible repair.

- Medical or surgical intensive care consultation for definitive disposition.

References / Further Reading

- Rosen, Peter, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier, 2018.

- Tintinalli, Judith E. Emergency Medicine: a Comprehensive Study Guide. McGraw-Hill, 2011.

- Marino, Paul L. Marino’s the ICU Book. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014.

- Søreide, Jon, and Asgaut Viste. “Esophageal Perforation: Diagnostic Work-up and Clinical Decision-Making in the First 24 Hours.” Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, vol. 19, no. 1, 2011, p. 66., doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-66.

- Vidarsdottir, H., et al. “Oesophageal Perforations in Iceland: a Whole Population Study on Incidence, Aetiology and Surgical Outcome.” The Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeon, vol. 58, no. 08, 2010, pp. 476–480., doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250347.

- Romero, Ronald V., and Khean-Lee Goh. “Esophageal Perforation: Continuing Challenge to Treatment.” Gastrointestinal Intervention, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1016/j.gii.2013.02.002.

- Kaman, Lileswar. “Management of Esophageal Perforation in Adults.” Gastroenterology Research, 2011, doi:10.4021/gr263w.

- Bhatia, Pankaj, et al. “Current Concepts in the Management of Esophageal Perforations: A Twenty-Seven Year Canadian Experience.” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, vol. 92, no. 1, 2011, pp. 209–215., doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.131.

- Sepesi, Boris, et al. “Esophageal Perforation: Surgical, Endoscopic and Medical Management Strategies.” Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, vol. 26, no. 4, 2010, pp. 379–383., doi:10.1097/mog.0b013e32833ae2d7.

- Brinster, Clayton J, et al. “Evolving Options in the Management of Esophageal Perforation.” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, vol. 77, no. 4, 2004, pp. 1475–1483., doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.037.

- Elsayed, H, et al. “The Impact of Systemic Fungal Infection in Patients with Perforated Oesophagus.” The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, vol. 94, no. 8, 2012, pp. 579–584., doi:10.1308/003588412×13373405388095.

- Shaker, Hudhaifah, et al. “The Influence of the ‘golden 24-h rule’ on the Prognosis of Oesophageal Perforation in the Modern Era.” European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, vol. 38, no. 2, 2010, pp. 216–222., doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.030.

2 thoughts on “Esophageal Perforation: Pearls and Pitfalls for the Resuscitation Room”

Pingback: May FOAMed - FRCEM Success

Pingback: ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography) Complications