Author: Brit Long, MD (@long_brit, EM Attending Physician, San Antonio, TX) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 77-year-old female presents with left proximal femur and hip pain after falling from a standing position. She tripped over a rug and landed on her left side. She denies LOC, neck pain, fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, or any other complaints. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Initial VS include T 37.2C, HR 92, BP 118/61, RR 18, SpO2 97% RA.

Exam reveals an otherwise well-appearing patient with normal mental status. Her left leg is shortened and externally rotated. Her pulses in the leg are normal, and she is able to move her foot and toes.

What are your next steps, and what is the likely diagnosis?

Answer: Proximal femur fracture, intertrochanteric

- Background: Femur fractures occur with a variety of mechanisms and are based on the specific location of fracture. Proximal femur fractures are associated with 22% all-cause mortality at 30 days and 36% at one year.

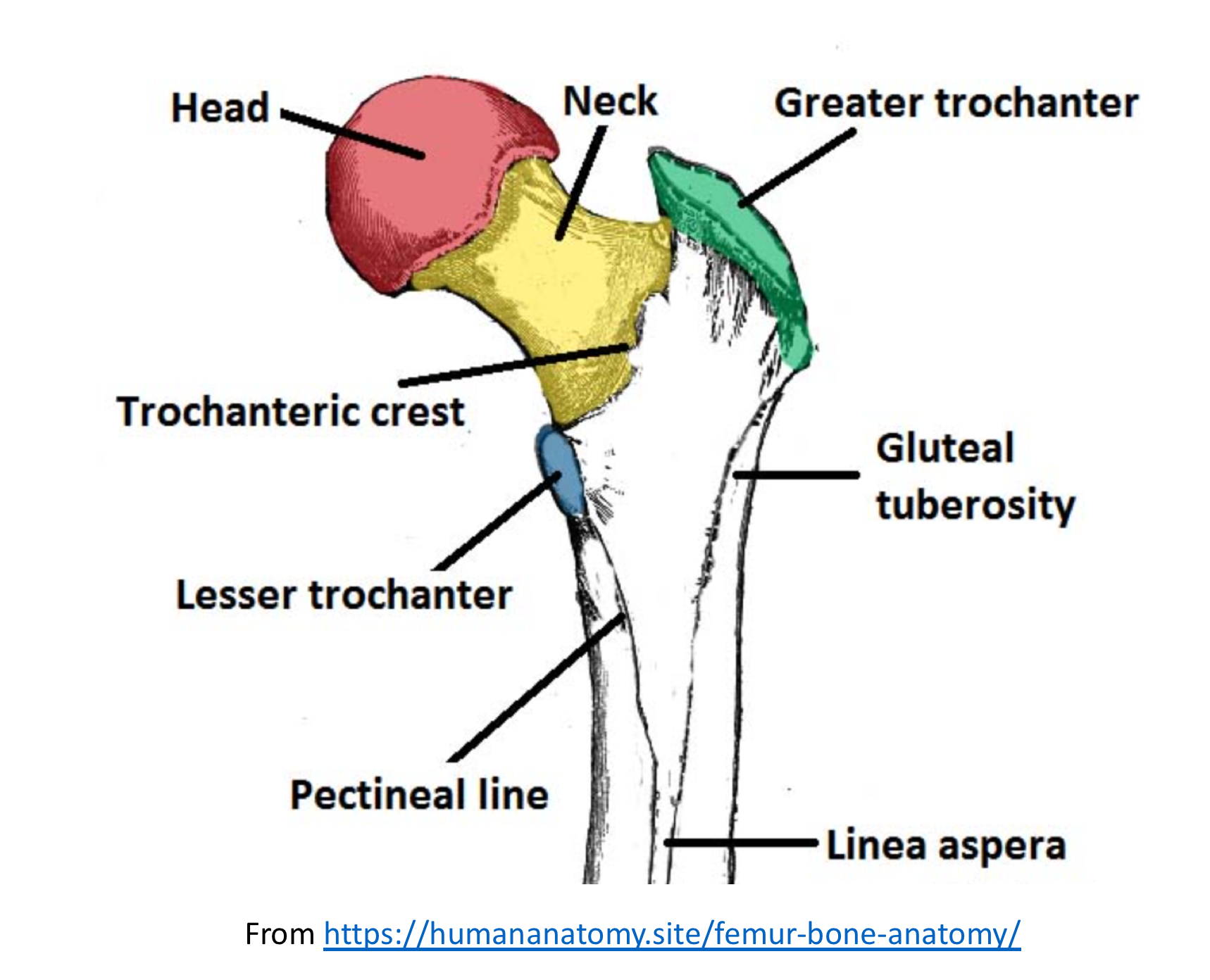

- Proximal: Intracapsular (femoral head or neck) and Extracapsular (intertrochanteric and trochanteric).

- Shaft: Mid shaft femur fracture (subtrochanteric).

- Femoral head has 3 arterial supplies: extracapsular arterial ring, ascending cervical branches, and artery to ligamentum teres.

- Intertrochanteric fractures account for 50% of proximal femur fractures, with more females than males affected (3:1).

- Mechanism:

- Head: Usually high energy trauma or dislocation. Often with other injuries (acetabular fracture, sciatic nerve neuropraxia, ipsilateral knee injury, femoral neck fracture, dislocation).

- Neck: Usually in older patients with osteoporosis and fall.

- Intertrochanteric: Most fractures in elderly patients (90%) are due to a fall, while in younger patients, fractures are due to high energy trauma (MVC).

- Trochanteric: Greater trochanter fractures associated with direct trauma or avulsion injury (more common in adolescents). Lesser trochanter fractures are due to pathologic bone or avulsion injury (iliopsoas).

- Types:

- Head: Depends on Pipkin system (4 types)

- Type 1 is fracture below fovia/ligamentum, Type 2 is fracture above fovea/ligamentum, Type 3 is a Type 1/2 + femoral neck fracture, Type 4 is a type 1/2 + acetabular fracture.

- Trochanteric: Greater vs. Lesser Trochanter.

- Intertrochanteric:

- Stable: Intact posteromedial cortex, no to little comminution. Intact cortex prevents external rotation with load application.

- Unstable: Posteromedial cortex disruption with comminution of posteromedial cortex and subtrochanteric extension.

- Occult: Fracture not visible on X-ray and requires further imaging (MRI or CT).

- Head: Depends on Pipkin system (4 types)

- Examination: Depends on type of fracture, as femoral head fractures typically are associated with other injuries.

- Prioritize ABCs first! Evaluate neurovascular status of leg.

- Femoral head fracture with posterior dislocation: leg is shortened, adducted, internally rotated.

- Femoral head fracture with anterior dislocation: leg is shortened, abducted, externally rotated.

- Femoral neck fracture: Usually minimal bruising. If non-displaced, patients are usually ambulatory. If displaced, leg is externally rotated and shortened.

- Trochanteric: Greater trochanter fractures associated with pain with abduction and tenderness over site. Lesser trochanter fractures are associated with ability to ambulate and groin pain with leg flexion.

- Intertrochanteric: Patients with non-displaced fractures may have minimal pain and be ambulatory. Displaced fractures are associated with pain, inability to ambulate, shortened and externally rotated leg.

- Evaluation:

- Consider cause of trauma or fall (syncope, ACS, PE), evaluate for other injuries (head, C-spine, rib fractures, upper extremity injuries), and complications from fall (rhabdomyolysis, etc.).

- If fracture is diagnosed and patient requires admission, then CBC, chemistry, coagulation panel, and type & screen may be requested by inhospital providers.

- Imaging:

- X-ray: Recommend AP pelvis, AP and cross table lateral hip, AP femur.

- For intertrochanteric fractures, occult fractures occur in up to 10% of patients with negative X-ray. Of all fractures, 8% are seen on CT with negative X-rays, with a further 2% seen on MRI but not CT and X-ray.

- If patients fail to bear weight after negative X-ray, obtain further imaging.

- Treatment:

- Manage other injuries or complications.

- Femoral Head Fracture: Orthopedic consultation, analgesia, emergent closed reduction if dislocation present.

- Femoral Neck Fracture: Orthopedic consultation, analgesia. Avoid skeletal traction, which compromises vascular flow to the femoral head.

- Trochanter: Non-weight bearing with orthopedic follow up in 1-2 weeks.

- Intertrochanteric:

- Analgesia: Femoral nerve blocks or fascia iliaca compartment blocks improve outcomes including pain, mortality, and long-term functional outcomes.

- Evaluate and monitor for blood loss, as up to 40% of patients require transfusion (intertrochanteric fractures are 2X as likely to need transfusion than other proximal femur fractures).

- Disposition is typically admission for further management.

- Operative: Stable injuries can be treated with sliding hip screw, while unstable are treated with intramedullary hip screw or arthroplasty.

- Nonoperative management is recommended for patients with high risk of perioperative complications or mortality, or those who are otherwise non-weightbearing. The goal of nonoperative treatment is early bed to chair mobilization.

- Prognosis: Depends on type of fracture.

- 1 year mortality for intertrochanteric fractures may reach over 30%.

- Mortality worse with older age, multiple comorbidities, male, and long delay to surgery (>2 days).

An 83-year-old woman presents with left hip pain after a mechanical fall. Her examination is unremarkable except for pain with range of motion of the left hip. Hip and pelvis X-rays are unremarkable. The patient continues to be unable to ambulate. What management is indicated?

A. Bone scan of the hip

B. CT scan of the hip

C. Discharge home with walker

D. MRI of the hip and pelvis

Answer: D

This patient’s presentation is concerning for an occult hip fracture, which can be diagnosed with an MRI. Hip fracture is more common in older patients and more common in women than in men. Patients with large hip fractures often present with an externally rotated and shortened lower extremity. However, some patients with hip fractures that are small will not have these findings. Patients will typically have pain with straight leg raise or log roll of the affected leg. In patients with negative X-rays, ambulation should be attempted. However, if the patient is unable to ambulate or can only ambulate with marked difficulty, further imaging should be pursued to rule out an occult hip fracture. MRI of the hip is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice because of its high sensitivity and specificity as well as an accuracy of 100%.

A bone scan of the hip (A) is sensitive and specific only when performed in the non-acute setting. CT scan of the hip (B) is commonly ordered because of its availability but has a 66% misdiagnosis rate. Patients who remain unable to ambulate after negative X-rays should not be discharged home (D) as missing an occult fracture can lead to increased morbidity.

No podcast link available

FOAMed:

https://www.orthobullets.com/trauma/1039/subtrochanteric-fractures

http://www.orthobullets.com/trauma/1038/intertrochanteric-fractures?expandLeftMenu=true

https://emin5.com/2017/12/07/femur-fractures/

https://coreem.net/core/intertrochanteric-fractures/

http://highlandultrasound.com/femoral-block/

References:

- Steele M, Stubbs AM. Hip and Femur Injuries. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Smith WR et al. Chapter 2. Musculoskeletal Trauma Surgery. In: Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics, 5e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014.