Today on the emDOCs cast, Jess Pelletier and Brit Long cover benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus.

Episode 132: Benzodiazepine-Refractory Status Epilepticus

Background:

- Seizures are a common chief complaint in the ED, accounting for 1% of ED visits per year in the U.S.1

- Among patients with seizures, 22% have SE.2

- SE refers to a seizure lasting 5 or more minutes, or back-to-back seizures without a return to neurologic baseline in between.3

- SE is a self-sustaining condition.4 Risk of long-term neurologic damage becomes more likely once SE reaches the 30-minute mark.5

- Up to 40% of SE cases are actually refractory to benzodiazepines.6

- There can be SE with motor symptoms (convulsive SE is a subtype of that), or without motor symptoms (i.e., non-convulsive SE, NCSE) (Table 1).

Table 1. Differences in timing to note for subtypes of SE.5

| Type of SE | Duration of Seizure Needed to Call it SE (in minutes) | Duration of Seizure Suspected to Cause Long-Term Neurologic Damage (in minutes) |

| Convulsive | 5 | 30 |

| Focal/partial, with impaired LOC | 10 | >60 |

| Absence | 10-15 | Unknown |

Table 2. SE subtypes.5

| Motor Symptoms Present? (yes/no) | Subtypes | ||

| Yes (i.e., CSE) | Convulsive | Focal onset → secondary generalization

Generalized Unknown whether either of the above |

|

| Myoclonic | With or without coma | ||

| Focal motor | Adversive status

EPC Ictal paresis Oculoclonic status Repeated motor |

||

| Tonic | |||

| Hyperkinetic | |||

| No (i.e., NCSE) | With coma | ||

| Without coma | Generalized | Atypical absence

Myoclonic absence Typical absence |

|

| Focal | Aphasic

With impaired consciousness Without impaired consciousness |

||

CSE = convulsive SE, EPC = epilepsia partialis continua, NCSE = non-convulsive SE, SE = status epilepticus.

- Up to 11% of SE cases have new neurologic disabilities; higher risk of in kids.7

- Mortality ranges between 15%-33% .8 Unfortunately, these numbers have not improved over time.9

Differential Diagnosis:

- Significant differential of potential underlying causes for benzodiazepine-refractory SE (Table 3).10

Table 3. Potential causes of benzodiazepine-refractory SE.10

| Body System | Underlying Cause |

| Endocrine or Metabolic | Cerebral edema from DKA

Electrolyte derangements – hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypo-/hypernatremia, hypophosphatemia HHS Uremia |

| Infectious or Immune | Cerebral malaria

Encephalitis Meningitis Neurocysticercosis Tuberculous meningitis/tuberculoma |

| Neurologic | Brain mass or abscess

CVST Epilepsy ICH Ischemic stroke PRES |

| Obstetric | Eclampsia |

| Toxicologic | Carbon monoxide poisoning

Drug intoxication or withdrawal Alcohol withdrawal Benzodiazepine/barbiturate withdrawal Cathinone intoxication Cocaine/methamphetamine intoxication GHB intoxication MDMA intoxication Opioid overdose (especially fentanyl, tramadol) Synthetic cannabinoid intoxication Isoniazid Seizure threshold-lowering medications Amphetamines Antibiotics (cephalosporins, PCN, fluoroquinolones) Antipsychotics Bupropion Carbamazepine Phenytoin SSRI/SNRI TCA |

| Traumatic | TBI |

CVST = cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis, GHB = gamma-hydroxybutyrate, HHS = hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, MDMA = 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, PCN = penicillin, PRES = posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SNRI = selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, TBI = traumatic brain injury, TCA = tricyclic antidepressant.

Assessment:

History

- Obtain a thorough history is essential.

- Speak with EMS, bystanders, or friends/family for collateral information to find out about triggers and seizure features.11–13

- Clarify type of seizure, duration, whether it has broken at any point, whether the patient had a return to baseline between seizures, and whether they fell during the seizure (sustaining potential injuries).

- Obtain a travel history is important (malaria 14,15 and tuberculosis16,17 can cause meningitis and encephalitis, leading to seizure activity).

- For patients with HIV, space-occupying lesions are possible and can lead to seizures (toxoplasmosis and CNS lymphoma).

Labs

- Point-of-care (POC) glucose is vital; hypoglycemia is an easily reversible cause of seizure activity.18

- Other important labs for patients presenting with SE include:10

- ASM levels (for patients taking them).19

- Basic metabolic panel (BMP), calcium, and magnesium – electrolyte derangements that could trigger a seizure.

- Complete blood count (CBC) – for leukocytosis that might suggest infection, or thrombocytopenia that might raise concern for conditions like thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

- Inflammatory markers – CRP and ESR to look for signs of infection

- Renal and liver function tests (LFTs)11 – derangements of LFTs can occur from ASM use, and acute kidney injury (AKI) can occur secondary to rhabdomyolysis from prolonged seizure activity.

- Pregnancy testing, where applicable19 – exclude eclampsia as the cause of seizures (since the management differs drastically).

- Toxicology testing20 – look for potential intoxicants. In patients with alcohol use disorder, a blood alcohol level of 0 may raise concern for alcohol withdrawal seizures. However, patients who chronically “live” at elevated levels may have withdrawal seizures at elevated alcohol levels.

- Infectious testing, for those having signs and symptoms21

- Lactate, if questioning whether this was really a seizure22,23

- This will only really help in the first two hours after a tonic-clonic seizure; it is less helpful in the setting of other seizure types

- Creatine kinase (CK), if there is concern for rhabdomyolysis (which can happen with prolonged seizures).24

Imaging

- Computed tomography (CT) before lumbar puncture (LP) is important if concerned for meningitis/encephalitis to rule out signs of increased intracranial pressure.

- If there is a high suspicion of meningitis or encephalitis, start antibiotics and antivirals before LP.

- Every SE patient needs a CT in the ED once they are stabilized.12

- For patients with known seizure disorders, CT is typically unnecessary- unless they have high-risk features (brain tumor, history of cancer, current treatment with chemotherapy, immune compromise, trauma that might have caused the seizure, if they are on anticoagulation, if the seizure activity is different from prior seizures or if it has a new focal element to it).25

- CT’s ability to visualize posterior fossa lesions is poor; MRI indicated if this is high on the differential.26–29

- All SE patients without a clear cause for their seizure need an MRI eventually to look for potential anatomic triggers, but MRI does not need to take place acutely.30–37

Other Important Diagnostics

- Obtain ECG to identify potential causes of syncope: heart blocks, prolonged QTc, Brugada syndrome, etc.

- Arrhythmias are a common mimic.

- Emergent EEG for patients actively seizing, if they don’t return to their normal neuro baseline within 30-60 minutes after seizure activity is terminated, or if they have new neuro deficits without a clear structural cause on imaging after their seizing has stopped.37

- Any seizure patient who ends up getting second- or third-line ASMs should likely undergo EEG.38

- If EEG is unavailable, transfer patient to a facility where they can see neurology and get an EEG once they are stabilized.

Management:

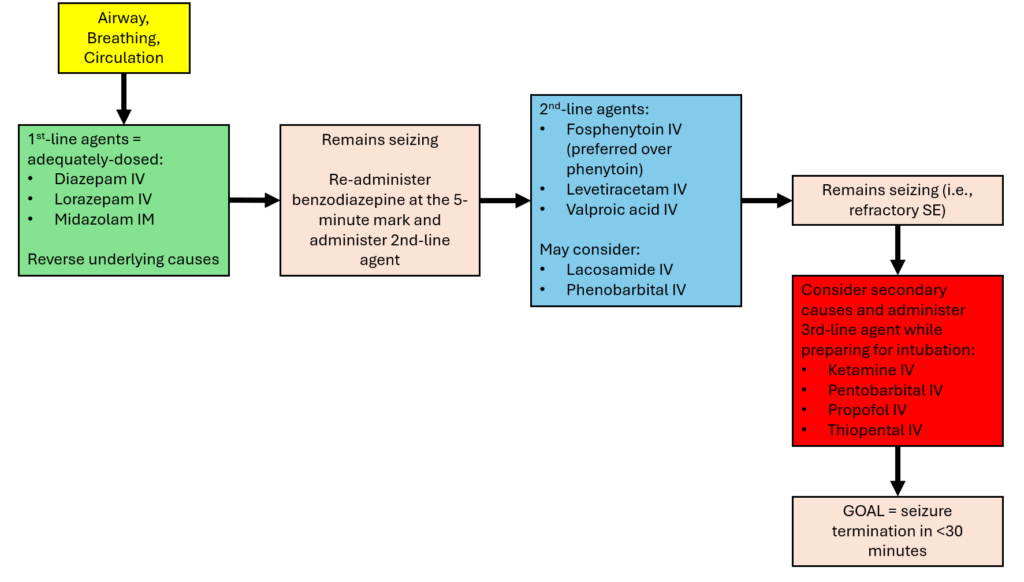

- Go through ABCs – airway, breathing, and circulation. Seizures can quickly lead to airway and breathing compromise.

- Log roll the patient onto their side (into the recovery position) to prevent aspiration, use airway maneuvers like head tilt chin lift or jaw thrust to open the airway, and utilize suction to remove vomit or secretions that could result in aspiration.

- Autonomic dysfunction tends to accompany seizure activity; IV fluids may be necessary.

- Next address D – disability.

- Check for hypoglycemia and address any reversible causes if possible.

- First-line agents (benzodiazepines) should be administered at appropriate doses (Table 4).

- Benzodiazepines are underdosed the majority of the time,39 usually due to fears of suppressing respiration.

- Seizure activity itself is more likely to compromise breathing than benzodiazepines.40 Avoid underdosing.

- Early dosing of benzo’s at appropriate doses is imperative.

- If seizing after the first dose of benzodiazepines, and known reversible causes have been addressed, administer another dose of benzodiazepines.

- If 5 minutes have passed since the first dose of benzodiazepines, order second-line agents, with fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, or valproic acid being the agents of choice.3

- Fosphenytoin (and phenytoin) are not recommended for seizures that are toxicologically-induced; they are unlikely to help and may be harmful.

- If still seizing after several doses of benzodiazepines and a second-line agent, this is “refractory” SE.

- Likelihood of permanent neurologic damage or death increases after the 30-minute mark.41,42

- Consider third-line agents: ketamine, pentobarbital, propofol, or thiopental.

- Many of these agents will lead to respiratory depression;43 thus, the patient will likely require intubation with propofol infusion at this point, along with EEG.38

- *Consider ordering second and third line medications at the same time as the second dose of the benzodiazepine.* If continuing to seize following the second benzo dose, consider giving an agent like ketamine or propofol with preparations for intubation.

Figure 1. Suggested algorithm for status epilepticus management.

Table 4. ASM dosing.

| First-Line Agents38,44,45 | Drug | Route | Dose |

| Diazepam | IV | 0.15 mg/kg (max 10 mg per dose, may be repeated once) | |

| Rectal | 0.3–0.5 mg/kg (max 20 mg) | ||

| Lorazepam | IV | 0.1 mg/kg (max 4 mg per dose, may be repeated once) | |

| Midazolam | Buccal | 0.2 mg/kg | |

| IM | 10 mg | ||

| IN | 0.2 mg/kg | ||

| IV | 0.2 mg/kg | ||

| Second-Line Agents | Fosphenytoin3 | IV | 20 mg PE/kg (max 1500 mg PE) |

| Lacosamide46,47 | IV | 5–6.5 mg/kg over 15 min | |

| Levetiracetam3 | IV | 60 mg/kg (maximum, 4500 mg) | |

| Phenobarbital48–50 | IV | 15–20 mg/kg loading dose, no faster than 1 mg/kg/min; a second dose of 5–10 mg/kg may be given 10 min later | |

| Phenytoin50,51 | IV | 18 mg/kg (range 15–20) bolus, no faster than 50 mg/min | |

| Valproic acid3 | IV | 40 mg/kg (maximum, 3000 mg) | |

| Third-Line Agents | Ketamine52–55 | IV | 1.5–5 mg/kg loading dose → maximum infusion rate of 15 mg/kg/h |

| Pentobarbital49 | IV | 5–15 mg/kg, no faster than 1 mg/kg/min | |

| Propofol49,56 | IV | 1–2 mg/kg → infusion rate of 3–7 mg/kg/h | |

| Thiopental49 | IV | 2–7 mg/kg, no faster than 1 mg/kg/min |

Take-Home Points:

- SE is a high morbidity and mortality presentation in the ED with a vicious cycle – it gets hard to break the longer it goes on.

- Goal is to stop the seizure as soon as possible, particularly before 30 minutes of seizure.

- Go through the ABCs, and don’t forget to reverse hypoglycemia and look for other reversible causes.

- First-line is a benzo, then another benzo at the right dose. Progress to second- and third-line agents quickly to break the SE cycle.

References:

- Pallin DJ, Goldstein JN, Moussally JS, Pelletier AJ, Green AR, Camargo CA. Seizure visits in US emergency departments: epidemiology and potential disparities in care. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1(2):97-105. doi:10.1007/s12245-008-0024-4

- Honavar A, Anuranjana A, Markose A, Dani K, Yadav B, Abhilash KundavaramPP. Profile of patients presenting with seizures as emergencies and immediate noncompliance to antiepileptic medications. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(12):3977. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_864_19

- Smith MD, Sampson CS, Wall SP, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;84(1):e1-e12. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2024.02.018

- Niquet J, Baldwin R, Suchomelova L, et al. Benzodiazepine‐refractory status epilepticus: pathophysiology and principles of treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1378(1):166-173. doi:10.1111/nyas.13147

- Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus – Report of the Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515-1523. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- Byun JI. Management of convulsive status epilepticus: recent updates. encephalitis. 2023;3(2):39-43. doi:10.47936/encephalitis.2022.00087

- Choi SA, Lee H, Kim K, et al. Mortality, Disability, and Prognostic Factors of Status Epilepticus: A Nationwide Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurology. 2022;99(13). doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200912

- Lv RJ, Wang Q, Cui T, Zhu F, Shao XQ. Status epilepticus-related etiology, incidence and mortality: A meta-analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2017;136:12-17. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.07.006

- Neligan A, Noyce AJ, Gosavi TD, Shorvon SD, Köhler S, Walker MC. Change in Mortality of Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus in High-Income Countries Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(8):897. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1268

- Pelletier J, Merriman W, Koyfman A, Long B. Benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus: A narrative review. Am J Emerg Med. Published online September 2025:S0735675725006308. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2025.09.019

- Craig DP, Mitchell TN, Thomas RH. A tiered strategy for investigating status epilepticus. Seizure. 2020;75:165-173. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2019.10.004

- Lee RK, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Seizures and Epilepsy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(5):S293-S304. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.01.037

- Alessandri F, Badenes R, Bilotta F. Seizures and Sepsis: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):1041. doi:10.3390/jcm10051041

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidelines for Malaria.; 2023. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria

- Misra UK, Kalita J, Prabhakar S, Chakravarty A, Kochar D, Nair PP. Cerebral malaria and bacterial meningitis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14(Suppl 1):S35-39. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.83101

- Long B, Liang SY, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Tuberculosis: a focused review for the emergency medicine clinician. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(5):1014-1022. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.040

- Young N, Thomas M. Meningitis in adults: diagnosis and management. Intern Med J. 2018;48(11):1294-1307. doi:10.1111/imj.14102

- Hewett Brumberg EK, Douma MJ, Alibertis K, et al. 2024 American Heart Association and American Red Cross Guidelines for First Aid. Circulation. 2024;150(24). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001281

- Gettings JV, Mohammad Alizadeh Chafjiri F, Patel AA, Shorvon S, Goodkin HP, Loddenkemper T. Diagnosis and management of status epilepticus: improving the status quo. Lancet Neurol. 2025;24(1):65-76. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00430-7

- Deng B, Dai Y, Wang Q, et al. The clinical analysis of new-onset status epilepticus. Epilepsia Open. 2022;7(4):771-780. doi:10.1002/epi4.12657

- Yealy DM, Mohr NM, Shapiro NI, Venkatesh A, Jones AE, Self WH. Early Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in the Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force Report. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(1):1-19. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.02.006

- Patel J, Tran QK, Martinez S, Wright H, Pourmand A. Utility of serum lactate on differential diagnosis of seizure-like activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2022;102:134-142. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2022.10.007

- Doğan EA, Ünal A, Ünal A, Erdoğan Ç. Clinical utility of serum lactate levels for differential diagnosis of generalized tonic–clonic seizures from psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and syncope. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;75:13-17. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.07.003

- Paternostro C, Gopp L, Tomschik M, et al. Incidence and clinical spectrum of rhabdomyolysis in general neurology: a retrospective cohort study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(12):1227-1234. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2021.09.012

- Isenberg DL, Lin A, Kairys N, et al. Derivation of a clinical decision instrument to identify patients with status epilepticus who require emergent brain CT. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(2):288-291. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.05.004

- Loevner LA. Imaging features of posterior fossa neoplasms in children and adults. Semin Roentgenol. 1999;34(2):84-101. doi:10.1016/S0037-198X(99)80024-8

- Bray HN, Sappington JM. A Review of Posterior Fossa Lesions. Mo Med. 2022;119(6):553-558.

- Hwang DY, Silva GS, Furie KL, Greer DM. Comparative Sensitivity of Computed Tomography vs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detecting Acute Posterior Fossa Infarct. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(5):559-565. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.101

- Kuzniecky RI. Neuroimaging of epilepsy: therapeutic implications. NeuroRx J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2005;2(2):384-393. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.2.384

- Tranvinh E, Lanzman B, Provenzale J, Wintermark M. Imaging Evaluation of the Adult Presenting With New-Onset Seizure. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(1):15-25. doi:10.2214/AJR.18.20202

- Pascarella A, Manzo L, Marsico O, et al. Investigating Peri-Ictal MRI Abnormalities: A Prospective Neuroimaging Study on Status Epilepticus, Seizure Clusters, and Single Seizures. J Clin Med. 2025;14(8):2711. doi:10.3390/jcm14082711

- Bosque Varela P, Machegger L, Oellerer A, et al. Imaging of status epilepticus: Making the invisible visible. A prospective study on 206 patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;141:109130. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109130

- Sarria‐Estrada S, Santamarina E, Quintana M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in focal‐onset status epilepticus. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(1):3-11. doi:10.1111/ene.15065

- Bosque Varela P, Machegger L, Crespo Pimentel B, Kuchukhidze G. Imaging of Status Epilepticus. J Clin Med. 2025;14(9):2922. doi:10.3390/jcm14092922

- Requena M, Sarria-Estrada S, Santamarina E, et al. Peri-ictal magnetic resonance imaging in status epilepticus: Temporal relationship and prognostic value in 60 patients. Seizure. 2019;71:289-294. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2019.08.013

- Cornwall CD, Dahl SM, Nguyen N, et al. Association of ictal imaging changes in status epilepticus and neurological deterioration. Epilepsia. 2022;63(11):2970-2980. doi:10.1111/epi.17404

- Gavvala JR, Schuele SU. New-Onset Seizure in Adults and Adolescents: A Review. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2657. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.18625

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(1):48-61. doi:10.5698/1535-7597-16.1.48

- Sathe AG, Underwood E, Coles LD, et al. Patterns of benzodiazepine underdosing in the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial. Epilepsia. 2021;62(3):795-806. doi:10.1111/epi.16825

- Kapur J. Strategies to innovate emergency care of status epilepticus. Neurotherapeutics. 2025;22(1):e00514. doi:10.1016/j.neurot.2024.e00514

- Cheng JY. Latency to treatment of status epilepticus is associated with mortality and functional status. J Neurol Sci. 2016;370:290-295. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2016.10.004

- Pan Y, Feng Y, Peng W, Cai Y, Ding J, Wang X. Timing matters: there are significant differences in short-term outcomes between two time points of status epilepticus. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):348. doi:10.1186/s12883-022-02868-y

- Huff JS, Morris DL, Kothari RU, Gibbs MA, The Emergency Medicine Seizure Study Group (Emssg)*. Emergency Department Management of Patients with Seizures: A Multicenter Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(6):622-628. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00175.x

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2103-2113. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1905795

- Lee SK. Diagnosis and Treatment of Status Epilepticus. J Epilepsy Res. 2020;10(2):45-54. doi:10.14581/jer.20008

- Hahn CD, Novy J, Rossetti AO. Comparison of lacosamide, levetiracetam, and valproate as second‐line therapy in adult status epilepticus: Analysis of a large cohort. Epilepsia. 2025;66(5). doi:10.1111/epi.18380

- Strzelczyk A, Zöllner JP, Willems LM, et al. Lacosamide in status epilepticus: Systematic review of current evidence. Epilepsia. 2017;58(6):933-950. doi:10.1111/epi.13716

- Jain P, Aneja S, Cunningham J, Arya R, Sharma S. Treatment of benzodiazepine-resistant status epilepticus: Systematic review and network meta-analyses. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2022;102:74-82. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2022.09.017

- Chen HY, Albertson TE, Olson KR. Treatment of drug-induced seizures. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):412-419. doi:10.1111/bcp.12720

- Trinka E, Höfler J, Leitinger M, Brigo F. Pharmacotherapy for Status Epilepticus. Drugs. 2015;75(13):1499-1521. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0454-2

- Singh SP, Agarwal S, Faulkner M. Refractory status epilepticus. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17(Suppl 1):S32-36. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.128647

- Rosati A, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Ketamine for Refractory Status Epilepticus: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(11):997-1009. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0569-6

- Buratti S, Giacheri E, Palmieri A, et al. Ketamine as advanced second‐line treatment in benzodiazepine‐refractory convulsive status epilepticus in children. Epilepsia. 2023;64(4):797-810. doi:10.1111/epi.17550

- García-Ruiz M, Rodríguez PM, Palliotti L, et al. Ketamine in the treatment of refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus: Experience from two centres. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2024;117:13-19. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2024.01.013

- Höfler J, Trinka E. Intravenous ketamine in status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2018;59(S2):198-206. doi:10.1111/epi.14480

- Huff JS, Melnick ER, Tomaszewski CA, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(4):437-447.e15. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.018