Authors: Miguel A. Martínez-Romo, MD (EM Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, NYC Health+Hospitals/Kings County) and Sage W. Wiener, MD (Assistant Professor, Director of Medical ToxicologyDepartment of Emergency Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, NYC Health+Hospitals/Kings County) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long (@long_brit)

Case

A 34-year-old male presents to the ED via EMS with dyspnea, cough, and chest pain for the last 2 days. Triage vitals reveal a temperature of 38.2° C, P 102 bpm, BP 164/97, RR 22, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. Physical exam reveals bilateral rales on lung auscultation, a holosystolic murmur at the left-lower sternal border, track marks in the upper extremities, and tachypnea. EKG performed at triage reveals an incomplete right bundle-branch block, and bedside chest radiograph reveals vascular congestion.

Overview

Injection drug use is via the hypodermic needle, which was invented in the mid-1800’s and available for purchase in the U.S. by the late 1800’s/early 1900’s (1).

It is not exactly known when drug injections started to be abused, but it is postulated that the Civil War in the U.S. and the Franco-Prussian War in Europe might have been contributing factors by creating widespread morphine addiction (2).

Drug users usually inject drugs into their veins, but the arterial, subcutaneous (known as “skin popping”), and intramuscular routes are also used.

The most commonly injected drugs are opioids, but cocaine, amphetamine and amphetamine derivatives, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or any water-soluble drug may also be injected (1).

Epidemiology

According to CDC data from 2014, 27 million people aged 12 or older tried drugs in the last 30 days, about 1 in 10 Americans (3). It is estimated that 0.30% of the US population injected drugs in the past year, about 774,434 people (4). Injection drug use at any point during a lifetime in those 13 years or older was estimated at 2.6% of the US population, or approximately 6,612,488 people in 2011 (4).

According to an United Nations Office and Drugs and Crime report, in 2013 there were approximately 12.19 million (range: 8.48- 21.46 million) injection drug-users (abbreviated ‘PWID’, People Who Inject Drugs) in the world, or about 0.26% (range: 0.18- 0.46%) of the adult population aged 15-64 (1, 5).

There are numerous complications from injection drug use, some unique to the type of drug being used. The complications of every injectable drug are outside of the scope of this article; we will be focusing instead on complications of the injection route of drug use. However, some notable complications of a few injectable drugs will be discussed.

Complications of Injection Drug Use and Clinical Features

Immunological, Infectious, and Inflammatory

Drug use in itself, can in some cases cause hyperthermia. Cocaine and amphetamines are 2 well-known drugs that can cause hyperthermia. The causes of hyperthermia are many, and can include toxic reactions to the drugs, reactions to adulterants, withdrawal syndromes (6).

Of note is “Cotton fever,” which can develop a few hours after injection and is an inflammatory reaction to cotton balls used as filters for drug suspensions. It is characterized by fever and physical exam findings of tachypnea, tachycardia, abdominal pain, and inflammatory retinal nodules (6). Injection drug use in itself associated with immune system dysregulation, so before attributing fever to a drug reaction, active infection must be ruled out; if no source can be found, the patient should be admitted for observation pending blood culture results (6).

As with any foreign substance, injection drug use can also illicit a hypersensitivity reaction from the immune system, including urticaria, wheezing, and dyspnea.

Injection drug use also places users at risk of acquiring HIV and Hepatitis B and C. Worldwide it is estimated that 13.5% of PWID are HIV positive, and 52% of PWID worldwide are estimated to have Hepatitis C (1, 5). According to the CDC, Hepatitis B rates appear to be increasing in PWID, with the rates of Hepatitis B from 2006-2013 in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia increasing 114% in PWID (7).

Opportunistic infections due to HIV in PWID, endocarditis, CNS infections, pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections, and septic phlebitis will be discussed later in relevant sections of this article.

CNS

Altered mental status (AMS) is a common presentation of PWID. One of the more common explanations is drug intoxication and withdrawal. Opioids and sedative hypnotics (such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB) can cause confusion and mental status depression, while stimulant drugs such as amphetamines and cocaine can cause agitation and anxiety during intoxication. Additionally, withdrawal from a sedative hypnotic can present similarly to intoxication with a stimulant (8,9). Treatment for intoxication and withdrawal is usually supportive. When respiratory depression occurs, it is a sign of opioid overdose, and patients should be ventilated and treated with naloxone (Narcan), an opioid antagonist. (9).

While AMS can often be explained by acute intoxication or withdrawal, this should be a diagnosis of exclusion. Be wary of PWID who do not appear to metabolize and recover their mentation as expected and in those with signs of trauma and/or focal neurological deficits.

PWID are often subject to trauma. This can be simply from falls due to intoxication or trauma due to assault. This puts these patients at risk for epidural and subdural hematomas, as well as other forms of intracranial hemorrhage and TBI’s.

Embolic strokes can occur from septic emboli from endocarditis (10).

Even without trauma, subarachnoid and other spontaneous cerebral hemorrhages have been reported with stimulants such as amphetamines, PCP, and cocaine (6, 8, 11, 12).

PWID are also at risk of CNS infections. This includes brain abscesses, bacterial and fungal meningitis, and epidural abscesses (6). PWID are also at increased risk of vertebral osteomyelitis/discitis, which can develop into an epidural abscess through local extension (13). Those with HIV are at risk of toxoplasmosis and cryptococcal meningitis as well as CNS lymphoma.

Other causes of AMS or neurological abnormalities in PWID include septic emboli to CNS from endocarditis, mycotic aneurysms, and delayed leukoencephalopathy (6).

Because of all the potential CNS complications, the emergency physician should perform a thorough history and physical exam, with an emphasis on the neurological exam and pupillary exam, and look for any focal deficits, stroke-like syndromes, or AMS not explained by intoxication.

IV drug users, particularly those who use heroin, are at risk for tetanus; they accounted for 15% of cases of tetanus from 1998-2000 (14, 15). IV drug abuse has also been linked to botulism, particularly in those who practice “skin-popping” and those who use black-tar heroin (27). Suspect botulism in those with cranial nerve involvement, AMS, progressive symmetric paralysis, respiratory muscle weakness; suspect tetanus in those with jaw tightness, muscle cramping, muscle stiffness, and fevers.

Ophthalmologic

PWID are also at risk of acute impairment of visual acuity. Those with endocarditis can develop ‘Roth Spots,” which are white centered retinal hemorrhages traditionally thought to originate from septic emboli (16,17). This seeding from septic emboli leads to endogenous endophthalmitis, which in PWID can be bacterial or fungal (18, 19). Symptoms are typically acute and present with decreased visual acuity, eye pain, redness, and lid swelling; suspect a possible fungal source if symptoms develop over days to weeks (6, 19). In those with HIV, have a high index of suspicion for CMV and toxoplasmosis retinitis, as well as cryptococcal and MAC uveitis (6).

Cardiac

Perhaps one of the best-known complications of intravenous drug use (IVDU), infective endocarditis is a microbial infection of the endocardial surface of the heart, including the valves, chordae tendineae, sites of septal defects, or the mural endocardium (20). Septic emboli from endocarditis are also one of the sources of complications in other organs.

In endocarditis associated with IVDU, the endocarditis has right-sided predilection, with the tricuspid valve being involved in 60-70% of cases, followed by the mitral and aortic vales (20-30% of cases) (19). Staphylococcus aureus is the agent in most of the cases (60% to 70%), usually sensitive to methicillin (MSSA), although resistance (MRSA) can account for about one-fourth of cases (21, 22). The next most frequent organisms are streptococci (viridians streptococci, group A streptococcus), enterococci (15% to 20%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens and other gram-negative rods (<10%), and Candida sp (<2%) (21). Polymicrobial infection happens in about 5% of cases, usually caused by P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, Haemophilus, or Candida (21). Licking of needles and the use of contaminated reconstitution mixes, such as those containing lemon juice, tap water, toilet water, and saliva have been associated with atypical organisms and fungal infections (6). Endocarditis with negative blood cultures occurs in 5% to 10% of cases (21). Based on 2 studies, it was found that about 7-8.5% of febrile IV drug users without an initial source were found to have infective endocarditis once hospitalized (6, 21,22). All these percentages and proportions however have regional and temporal variations (21).

Signs and symptoms of infective endocarditis are fever, chills, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, night sweats, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, heart murmur, petechiae on the skin, conjunctivae, or oral mucosa, splinter hemorrhages, Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, Roth Spots, as well as other signs and symptoms depending on sites of embolization (6, 20, 25).

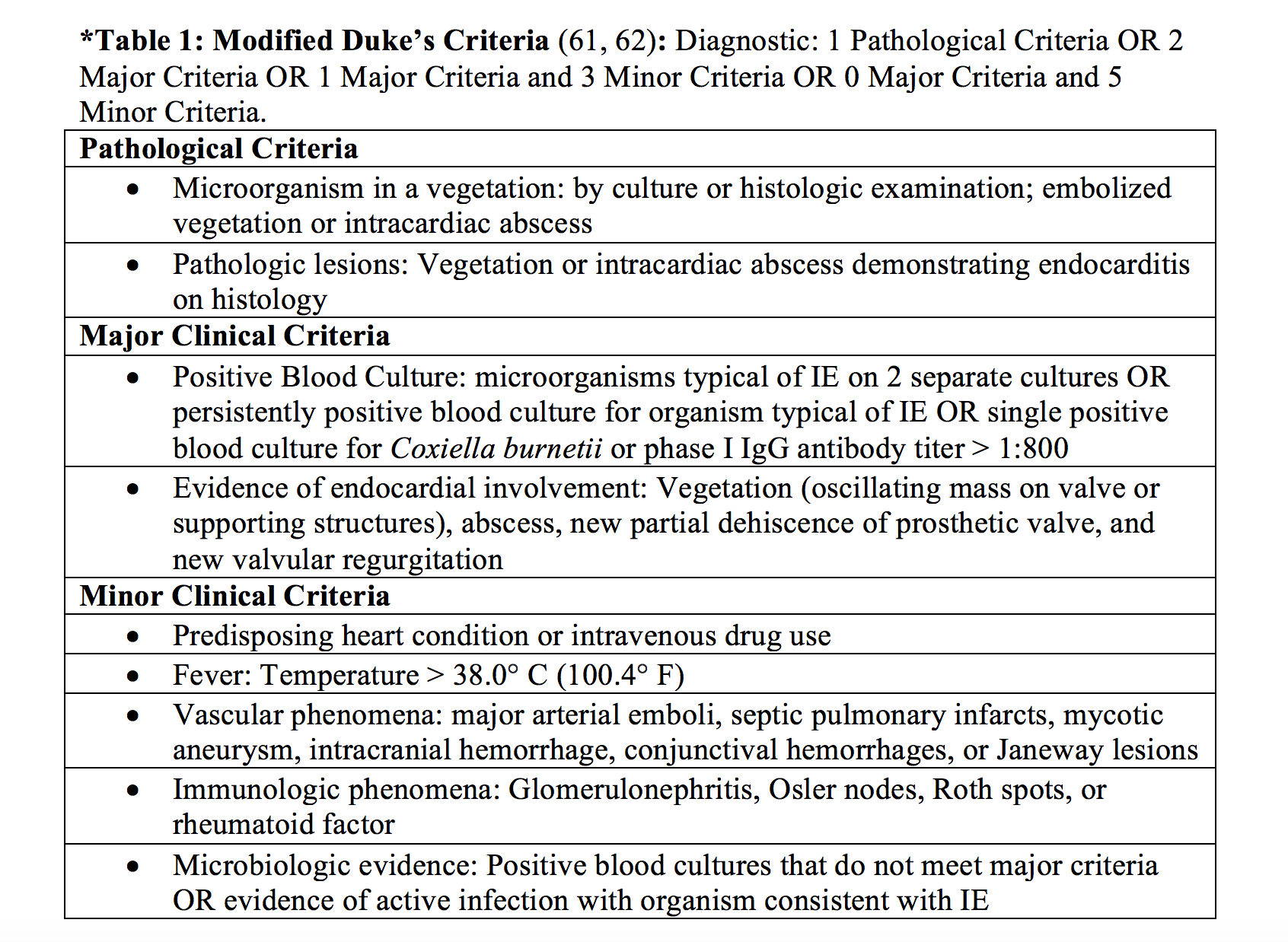

Diagnosis of infective endocarditis is based on clinical manifestations, blood cultures, echocardiography, and use of the modified Duke’s criteria (20, 25) [*Table 1].

Complications of infective endocarditis are many and include congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, atrioventricular (AV), fascicular, or bundle-branch blocks, Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm, mycotic aneurysms, pericarditis, hemopericardium and tamponade, pericarditis, fistulas to the right or left ventricle, and myocardial and aortic root abscess (20). Complications from septic emboli due to infective endocarditis to other organ systems are mentioned throughout this article in their respective sections.

Pulmonary

Dyspnea, cough, or chest pain can be a sign of a cardiac or pulmonary complication of endocarditis. Chest radiograph showing single, multiple, or segmented pulmonary infiltrates is a sign of septic emboli to the lungs; these can become cavitated or be associated with pleural effusions or empyema, and rarely, pneumothorax (21). Air or needle fragment emboli also occur (6).

One way in which PWID can develop a pneumothorax is through the use of a technique called a “pocket shot.” This technique involves injecting in the supraclavicular fossa in an attempt to reach the jugular, subclavian, or brachiocephalic veins (26). The approach is typically the same as the supraclavicular approach for placing a subclavian central venous catheter. This can lead to pneumothorax, hemothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinitis, or pneumomediastinum from performing valsalva to distend the neck veins (26).

Talc is a bulking agent that can be injected with IV drugs and can lead to pulmonary talcosis, in which talc particles travel to the pulmonary vasculature and interstitium and cause a granulomatous reaction (27). It can lead to acute respiratory failure, and as the disease progresses can lead to the conglomeration of micronodules into masses, emphysema, chronic respiratory failure, pulmonary hypertension, and right heart failure (27). It can present as diffuse infiltrates or ground-glass opacities on imaging (25).

IV drugs such as opioids and cocaine may result in non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema (12, 28). Opioids use can also lead to ARDS (9). Of note, acute opioid withdrawal caused by opioid antagonists such as naloxone may result in non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema and ARDS through a mechanism of massive sympathetic discharge (9).

PWID are at a 10-fold increase of community-acquired pneumonia (14). Acute intoxication puts them at risk of aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia (14). Patients with HIV are at risk of TB and Pneumocystis pneumonia (14).

Gastrointestinal, Splenic, Renal, and Hepatic

Most of the gastrointestinal complications from IVDU do not appear to be directly linked to IVDU itself or a sequelae of infective endocarditis, but rather seem to be an indirect consequence of the type of drug used itself. For example, opioid use and constipation causing abdominal discomfort, or withdrawal causing nausea/vomiting or diarrhea. However, although appearing to be very rare, there are a few case reports of septic emboli from infective endocarditis causing mesenteric ischemia (29, 30).

In those with abdominal pain, particularly left upper quadrant pain, the practitioner should also be concerned about possible splenic infract or splenic abscess from septic emboli (31).

Abdominal pain and/or flank pain should also raise suspicion for renal pathology. When infective endocarditis leads to renal infarcts, acute glomerulonephritis, acute interstitial nephritis, renal abscess, and/or renal cortical necrosis, patients may have pyuria or hematuria. (32, 33).

Hepatitis B and C are common amongst PWID, so the emergency medicine physician should be aware of hepatic complications, such as hepatic failure, hepatic encephalopathy, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, ascites, SBP, and variceal bleeding.

Dermatologic, Muscular, and Skeletal

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) in PWID are the most common reason for hospitalization and can lead to bacteremia and sepsis (34). Cellulitis commonly occurs, however the most common soft tissue infection in PWID is skin and soft tissue abscesses. Common sites are those commonly injected to: upper extremities including the antecubital fossa, lower extremities, and the groin (34). However, these can be found in other locations including buttocks, breasts, and abdomen (34). Risk factors for developing abscesses in PWID are dirty needles and the practice of “skin-popping,” in which the user injects subcutaneously or intramuscularly; “Booting,” in which users draw black blood before injecting a drug, also appears to be a risk factor for SSTIs (34).

SSTIs are commonly due to Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, although anaerobic and polymicrobial infection has also been reported in PWID (34).

Play close attention to the airway in those with potential SSTIs in the neck area, as the practice of the “pocket-shot” can lead to infection in the carotid triangle and result in airway obstruction or laryngeal edema (6).

PWID are at risk for necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) including subcutaneous tissue infection, necrotizing fasciitis, and myonecrosis (gas gangrene); these are less common, but life-threatening complications of SSTIs (34). As mentioned above, the practice of injecting into the groin or into the corpus cavernosa can lead to the NSTI Fournier’s gangrene (34,34). As such the practitioner should look for pain out of proportion to exam, hemorrhagic bullae, and crepitus, although in PWID an NSTI may masquerade as cellulitis or an abscess (34). NSTI is polymicrobial in nearly half the cases, including infections with Staphylococcal and Streptococcal species, Pseudomonas, Eikenella, Clostridium, and Prevotella species (34).

Hematogenous spread, extension of SSTI, or direct inoculation into muscle also puts PWID at risk for pyomyositis, an abscess-forming infection of skeletal muscle (34). Common locations include the deltoids, psoas, biceps, gastrocnemius, gluteals, and quadriceps (34). Infection is typically due to S. aureus, but polymicrobial infection has been reported (34).

Drugs such a heroin, cocaine and other stimulants, and drug adulterants, are also associated with the development of rhabdomyolysis (36).

Contiguous spread from SSTIs, direct inoculation, and hematogenous spread may result in septic arthritis or osteomyelitis in PWID (37). Subcutaneous abscesses can lead to tenosynovitis in the hand and compartment syndrome (34). Of those with septic arthritis, common pathogens include Staphylococcus species (including MRSA), Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, and Serratia species (37). As previously mentioned, vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis are common in PWID and can be complicated by epidural abscess, so practitioners should have a high-index of suspicion for PWID with back pain.

PWID are at risk of osteomyelitis of the clavicle and septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint due to the “pocket-shot” injection technique and other factors (24, 38). The most common risk factor for sternoclavicular septic arthritis in one study was IV drug use (6, 38).

Vascular

Intravenous injection can lead to septic phlebitis and thrombophlebitis, conditions in which the veins become infected (39). Infected pseudoaneurysms can occur with contaminated intra-arterial injections, causing subsequent necrosis and rupture, which can lead to hemorrhage and limb loss. The majority of pseudoaneurysms occur in the femoral artery, although they can also occur in the upper limb vessels (40). Direct intra-arterial injection can also lead to direct endothelial injury and subsequent thrombosis, subsequent particulate emboli leading to ischemia, and local intimal damage leading to large vessel arterial occlusion and limb edema (40). These processes put patients at risk for limb ischemia and compartment syndrome. For example, those who inject into the radial artery who develop significant tissue loss may require digital amputations and fasciotomy (40). Direct intra-arterial injection can also lead to vasoconstriction, which is usually transient (40).

Septic phlebitis can also lead to infected hematomas and infected venous pseudoaneurysms; the infected venous pseudoaneurysms are most commonly located in the femoral vein (41). Suspect an infected venous pseudoaneurysm in a patient with a history of groin injections, a groin mass, and fever (41). Due to the potential to confuse pseudoaneurysms as abscesses, consider US or contrast CT in all painful masses in PWID, particularly in the groin, and if pulsating (6). However, note that in venous pseudoaneurysm, a pulse or bruit may be absent (41).

Of note, cocaine in particular is vasculo-toxic, pro-thrombotic, causes vasoconstriction, and is associated with acute myocardial infarction (40).

Emergency Department (ED) Evaluation

As seen in the sections above, intravenous drug use has a plethora of potential complications. As such, the ED evaluation should be tailored to the specific complaint and presentation. However, we will present some general guiding principles.

As in any patient coming in to the emergency department, the first focus should be on the Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (ABC’s). Patients in respiratory failure or impending respiratory failure, or unable to secure their airway should be intubated. Any hemodynamically unstable patient should be resuscitated with intravenous access, IV fluids, placed on a cardiac monitor and if needed placed on vasopressors. Once resuscitated, a through head to toe exam should follow.

History (1, 6, 18, 23, 27)

If patient stability permits, a through history should be performed. If the patient is unable to give a history due to instability, AMS, or some other reason, history should be elicited through any companions, EMS, telephone contacts and/or through chart review.

What the Emergency Physician (EP) asks a patient will depend on the presentation; not all of these questions will apply to every scenario, but we present the following as a guide. The EP should try to illicit the following from their patient:

- Current or past history of drug use

- Route of administration of drugs used currently or in the past

- Directly asked if they have ever injected drugs

- If injected, IV route, intra-arterial, subcutaneous, or intramuscular

- Age of onset of drug use, frequency of use, and the last time they used

- Sites of injection: extremities, abdomen, chest, buttocks, groin, genitals, supraclavicular fossa

- New or used needles or syringes. Shared needles or syringes

- Do they lick needles, do they clean needles, do they clean their skin prior to use?

- Do they mix preparations with adulterants, tap water, toilet water, spit, juice, vinegar, pulverized pills, or any other substance?

- Do they or their drug partners use the “flash” or “flashblood” method in which a user draws back blood before passing it to another user

- Specifically ask what drug they used (heroin, cocaine, etc.)

- If came in voluntarily, specifically ask what their concern was that brought them in to the ED

- If involuntarily, ask partners or EMS what caused to bring patient in

- History of localized or systemic infections, HIV history, hepatitis history

- Endocarditis history or “heart infection,” “heart disease,” “heart murmur”

- Fevers, chills, systemic symptoms

- Do they feel intoxicated or like they are withdrawing?

- Altered, acting like normal self? If accompanied, ask these questions about the patient to companions

- Trauma, falls, loss of consciousness

- Back pain, changes in vision, headache, neurological deficits such as weakness, imbalance

- Cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, difficulties breathing, respiratory fatigue, hemoptysis, weight loss, malaise, night sweats, rash, redness, or bumps on the skin, particularly in the hands, feet, fingers, or nails, and of lower extremity edema

- Abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal distension, and upper or lower GI bleeding

- Changes in their urine, such as blood or cloudiness

- Cellulitis or abscesses, rash, bumps, masses, boils, bug or spider bites, changes to the skin, muscle pain, back pain, or pain to their joints

- If sites where they inject are swollen or feel pulsating, if they have pain to their extremities, have trouble with range of motion, loss of sensation, or if their extremities feel cold

Physical Exam

Due to the high rate of complications, the EP should perform a thorough head to toe exam. Again, the physical exam will be based on the presentation, the following is a suggested guide depending on the clinical presentation:

- Evaluate the ABCs

- Head trauma

- Pupillary exam, visual acuity, visual fields, slit-lamp exam

- Neurological examination including mental status, strength, CNs, cerebellar function, gait, and sensation

- Back and vertebral tenderness

- Inspect supraclavicular fossa for evidence of injection, infection, masses

- Ability to swallow and take a breath, changes in voice, neck masses

- Auscultate for heart murmurs, tachycardia, abnormal rhythms

- Lung sounds, wheezing, rales, decreased or asymmetric sounds

- Abdominal distension, tenderness, particular attention to LUQ, RUQ, flanks, CVA tenderness, organomegaly

- Signs of ascites, fluid waves, spider angiomata, caput medusa

- GU area and inguinal area for any signs of injection

- Complete head to toe skin exam including genitals, groin, buttocks

- Skin for evidence of IV drug use: track marks

- Skin for fluctuance, masses, erythema, discharge, tenderness, pain out of proportion, bullae, and crepitus

- Shaft of penis as corpus cavernosa is a site of injections (34)

- Lower extremity edema

- Extremities and joints for ROM, neurovascular function, including sensation, radial, DP, PT, femoral pulses, skin temperature

- Special areas of attention for skin: upper extremities, particularly the antecubital fossa, skin overlying the radial and brachial artery, lower extremities, inguinal area, buttocks, and the supraclavicular fossa and neck

- Masses or suspected abscesses should be palpated for pulsation and auscultated for bruits

EKG

Although the EKG is often normal in endocarditis, the EKG can play an important initial role in those patients in which you suspect infective endocarditis; possible findings include complete heart block, first degree heart block, Mobitz type II AV block, changes consistent with pericarditis, AV, fascicular, or bundle-branch blocks (18, 42). Those on cocaine can also have acute myocardial infarction, so an EKG should be performed on cocaine users with concerning symptoms. Cocaine users may also have QRS prolongation or dysrhythmias due to sodium channel blockade.

Imaging

Echocardiography is one of the critical steps in diagnosing and identifying complications of infective endocarditis and is one of the major modified Duke criteria (43). Besides aiding in diagnosis of endocarditis, it is helpful in assessing valvular function and ventricular function. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has a sensitivity of about 75% for native valve endocarditis, while Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has a sensitivity of over 90%; TEE is also better at detecting complications such as abscess, leaflet perforation, and pseudoaneurysm (43). TEE is considered the method of choice for those with prosthetic valves and cardiac devices, due to the poor sensitivities of TTE in those scenarios (43). Thus, an EP can attempt a bedside TTE, but if signs of endocarditis are identified, an inpatient TEE will still be needed to further assess any of its complications (43).

Chest radiography can reveal single, multiple, or segmented pulmonary infiltrates, which might represent consolidations from pneumonia or septic emboli. They can also reveal pleural effusions, empyema, pneumothorax, hemothorax, or vascular congestion from heart failure; in those with multiple septic pulmonary infiltrates, suspected pulmonary talcosis, or ARDS, a CT of the chest might be warranted (19, 24, 25).

Based on the clinical features and exam, also consider CT with contrast to investigate suspected NSTIs (44), or contrast CT or ultrasound for suspected pseudoaneurysm (6). Ultimate management should not be delayed, but consider CT Angiography and early vascular surgery consultation in those with suspected limb ischemia (45).

For those with loss of consciousness, AMS, or focal neurological deficits consider CT of the head. MRI of the spine should be done in those with suspected discitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, or epidural abscess (46).

Laboratory Studies

In febrile patients or those with suspected endocarditis, 3 separate blood cultures should be drawn, as positive blood cultures are one of the microbiologic cornerstones of the diagnosis of endocarditis and is one of the major modified Duke criteria (43).

Other laboratory studies are non-specific, but a complete blood count (CBC) might reveal a leukocytosis, leukopenia or anemia; inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in endocarditis or osteomyelitis; Rheumatoid Factor can be elevated in endocarditis; and a UA might reveal hematuria, pyuria, or casts (43, 47).

Consider LFTs and an INR in those with Hepatitis B or C and a type and screen in anyone with upper or lower GI bleeding, or for any potential surgical candidate.

If not diagnosed with HIV, consider testing for HIV because of the close association between intravenous drug use and HIV transmission. A CD4 count might help stratify for which opportunistic diseases a patient with HIV is at risk.

Emergency Department Management

Of vital importance and as previously mentioned, the EP should assess the ABCs and resuscitate as indicated. Obtain imaging, laboratory testing and ancillary testing as indicated above. ED management will depend on the particular clinical presentation or complaint of an intravenous drug user.

Fever (6)

- If known source of infection, treat accordingly. If unknown, treat as endocarditis until proven otherwise

- Admit as inpatient or observation until blood culture results known

CNS

AMS or Neurological Deficits

- Supportive care for drug intoxication or withdrawal

- If there is respiratory depression, ventilate and administer naloxone

- Drug intoxication and withdrawal should be treated as diagnosis of exclusion, if other pathologies are suspected, evaluate accordingly

- CT head, especially if with neurological deficits or recent trauma

- Consider CT head with and without contrast for those with HIV and low CD4

- LP as indicated

- MRI of spine if back pain or suspicion for epidural/spinal abscess

- Neurology consult as indicated

Ophthalmologic

Endogenous endophthalmitis (17, 48)

- Ocular Emergency

- Urgent ophthalmologist consultation

- External eye exam, including periorbital area, eye lids

- Visual acuity and fields

- Slit-lamp examination

- IV antibiotics: Vancomycin + aminoglycoside or 3rd generation cephalosporin, + clindamycin

- Admission for intravitreal antibiotics, vitreous cultures, evaluation of possible fungal etiology, and possible pars plana vitrectomy

Cardiac

Endocarditis (49)

- 3 sets of Blood cultures

- EKG

- Chest radiography

- TTE, will need inpatient TEE

- If medically stable antibiotics can await blood culture results

- If medically unstable/septic empiric coverage for IV drug use should cover S aureus, β-hemolytic streptococci, and aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, such as Vancomycin 30mg/kg IV and cefepime 2g IV

- Heart blocks: pacer pads, atropine, venous pacers as needed

Valve Rupture (50)

- Acute valve rupture causing florid CHF necessitates urgent cardiothoracic surgery consult for surgical repair (Class I indication AHA/ACC and ESC)

- Afterload reduction with strict cardiac and clinical monitoring while awaiting surgery

Pulmonary

Pneumonia

- Treat for CAP or HCAP as indicated

- High suspicion for TB, isolation

- If HIV + and high suspicion, LDH, arterial blood gas, blood cultures for PCP, prednisone if indicated by blood gas, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Septic pulmonary emboli (51, 52)

- Imaging: Chest radiography or CT chest

- Source control (treat underlying endocarditis)

- IV antibiotics (see infective endocarditis treatment)

- Admission, Cardiothoracic surgery consult for possible valve replacement

- Urgent Cardiothoracic surgery/IR consult if concern for ruptured mycotic pulmonary aneurysm caused by septic emboli for thoracotomy vs. coil embolization

Pulmonary talcosis (25)

- Supportive treatment

- Treat sequelae such as emphysema or pulmonary hypertension as indicated

Pneumothorax/Hemothorax

- Chest radiograph

- If clinical symptoms of tension pneumothorax, needle decompression followed by chest thoracostomy

- Otherwise oxygen, pig tail catheter, chest thoracostomy as indicated

Air/fragment emboli (53, 54, 55)

- Air embolism, TEE, TTE, CT chest for diagnosis

- Air embolism immediately place in left-lateral decubitus and Trendelenburg. Give oxygen. If CPR needed, place in supine, head-down position.

- Air embolism, transfer to hyperbaric oxygen therapy facility; if not feasible, admit to ICU with oxygen supplementation

- Needle fragment embolization, CT chest

- Needle fragment embolization causing cardiac wall perforation, cardiac wall necrosis, urgent Cardiothoracic surgery consultation

- Needle fragment causing caval thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism, anticoagulants, vascular surgery consult

Gastrointestinal, Splenic, Renal, and Hepatic

GI

- Treat constipation with laxatives, stool softeners

- Nausea, vomiting from opioid withdrawal supportive care, methadone; benzodiazepines or clonidine may be considered if methadone not available

- Mesenteric ischemia unlikely unless cocaine is involved; if suspicion, urgent surgery consult, CTA abdomen, IVF, analgesia

Splenic infarct (56)

- CT with IV contrast, analgesia

- Splenic infarction alone is not an indication for surgery

- Indications for surgery are complications from splenic infarct, including persistent symptoms, splenic abscess, massive subcapsular hemorrhage, splenic rupture, and an underlying hematological condition

Renal infarct (57, 58)

- CT with IV contrast, LDH, LFTs, UA

- Gold standard has not been established but since the embolus is septic, broad-spectrum antibiotics (see endocarditis)

- Anticoagulation is also recommended

- Surgery and IR consult for possibility of endovascular therapy vs. surgery

Dermatologic, Muscular, and Skeletal

SSTI (6, 33)

- Oral vs. IV antibiotics as indicated

- I & D for abscesses, consider CT or ultrasound to evaluate for pseudoaneurysm

- Consider CT with IV contrast if suspicion for NSTI, pyomyositis

NSTI (33)

- Urgent surgical consult for debridement

- IV antibiotics

- CT with IV contrast

Septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, tenosynovitis (6, 33, 36)

- Urgent Orthopedic surgery consult

- MRI for vertebral osteomyelitis

- IV antibiotics

- Joint aspiration

Vascular

Septic thrombophlebitis (59)

- US or CT to visualize thrombus

- Blood cultures

- IV antibiotic regimen as per endocarditis guidelines

Infected pseudoaneurysm (40, 60)

- Duplex ultrasound, MRA if negative and if high suspicion

- IV antibiotics

- Vascular surgery consult for possible excision, ligation, debridement, or arterial reconstruction

Limb Ischemia (40)

- Urgent vascular surgery consult

- Test neurovascular function, including sensation, motion, and pulses

- Doppler/ABI

Case Resolution

The patient becomes increasingly tachypneic. Fearing decompensation, the EP starts empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and cefepime, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, and afterload reduction with nitroglycerin. Cardiothoracic surgery is consulted, and the patient is admitted to the hospital. Inpatient TEE reveals right-sided vegetations, right ventricular failure, and confirms new tricuspid regurgitation. Blood cultures eventually grow Staphylococcus aureus. Diagnosis is made via the modified-Duke’s criteria. IV antibiotics and afterload reduction are continued, and the patient is ultimately taken to the OR for surgical repair of the tricuspid valve.

Take Home Points

- Not all hyperthermia is fever. However, approach all hyperthermia as fever from infection in PWID until clinically proven otherwise. PWID may have elevated temperature from excess heat production with agitation after stimulant use and from inflammation. If no alternative for infection is found, admit with blood cultures.

- Be cautious about attributing AMS to drug intoxication, particularly in patients who are not improving as expected. Consider infections, thromboembolic events, intracranial hemorrhage, and trauma in your differential diagnosis.

- Consider injection drug use as a systemic disease, because accessing the blood stream can lead to adverse effects in every organ system.

- Empiric antibiotics for endocarditis can await blood culture results unless the patient is unstable.

- Beware attributing a dermatological finding as an SSTI, keep NSTIs and pseudoaneurysm on the differential.

References / Further Reading

- Baciewicz GJ. Injecting Drug Use. Retrieved from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/286976-overview Accessed: 11/20/2017. Published: 3/31/16

- Fisher GL, Roget NA. Encyclopedia of Substance Abuse Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery. Sage Publications, 2009.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). http://www.samhsa.gov/ data/ Accessed 11/20/2017.

- Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, et al. Estimating the Number of Persons Who Inject Drugs in the United States by Meta-Analysis to Calculate National Rates of HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Infections. Baral S, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97596. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097596.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, World Drug Report 2015 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.15.XI.6). Retrieved from http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed: 11/20/17

- Grosheider T, Shepherd SM. Injection Drug Users. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/featuredtopics/youngpwid.htm Accessed 11/21/17

- Jang DH. Amphetamines. In: Hoffman RS, Howland M, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 10e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015.

- Nelson LS, Olsen D. Opioids. In: Hoffman RS, Howland M, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 10e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015.

- Epaulard O, Roch N, Potton L, Pavese P, Brion JP, Stahl JP. Infective endocarditis-related stroke: diagnostic delay and prognostic factors. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009. 41(8):558-62.

- McGee SM, McGee DN, McGee MB. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage related to methamphetamine abuse: autopsy findings and clinical correlation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004 Dec;25(4):334-7.

- Prosser JM, Hoffman RS. Cocaine. In: Hoffman RS, Howland M, Lewin NA, Nelson LS, Goldfrank LR. eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 10e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015.

- Chuo CY, Fu YC, Lu YM, Chen JC, Shen WJ, Yang CH, Chen CY. Spinal infection in intravenous drug abusers. Spinal Disord Tech. 2007 Jun;20(4):324-8.

- Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Bacterial Infections in Drug Users. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005; 353:1945-1954. November 3, 2005. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra042823

- Pascual FB, McGinley EL, Zarardi LR, Cortese MM, Murphy TV. Tetanus surveillance — United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Surveill Summ2003;52:1-8 Accessed: 11/27/17

- Sethi K, Buckley J, de Wolff J. Splinter haemorrhages, Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions and Roth spots: the peripheral stigmata of endocarditis. British Journal Of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005) [serial online]. September 2013;74(9):C139-C142. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 22, 2017.

- Ceglowska K, Nowomiejska K, Kiszka A, Koss MJ, Maciejewski R, Rejdak R. Bilateral Macular Roth Spots as a Manifestation of Subacute Endocarditis. Case Reports in Ophthalmological Medicine. 2015;2015:493947. doi:10.1155/2015/493947.

- Patel SN, Rescigno RJ, Zarbin MA: Endogenous endophthalmitis associated with intravenous drug abuse. Retina34(7): 1460-1465, 2014. doi:1097/IAE.0000000000000084

- Egan DJ. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/799431-overview Accessed: 11/22/17

- Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1318-1330. November 1, 2001 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra010082

- Miró JM, del Rı́o A, Mestres CA. Infective endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers and HIV-1 infected patients. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Jun;16(2):273-95, vii-viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5520(01)00008-3

- Ji Y, Kujtan L, Kershner D. Acute endocarditis in intravenous drug users: a case report and literature review. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives. 2012;2(1):10.3402/jchimp.v2i1.11513. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v2i1.11513.

- Chung-Esaki H, Rodriguez R, Alter H, Cisse B. Validation of a prediction rule for endocarditis in febrile injection drug users. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Volume 32. May 2014 Volume 32 Issue 5, 412 – 416. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.008

- Rodriguez R, Alter H et al. A pilot study to develop a prediction instrument for endocarditis in injection drug users admitted with fever. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. October 2011 Volume 29, Issue 8, 894 – 898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2010.04.006

- Brusch JL. Infective Endocarditis. Mesdcape. Retrieved from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/216650-overview. Accessed: 11/24/17

- McCarroll KA, Roszler MH. Lung disorders due to drug abuse. Journal Thoracic Imaging.1991 Jan;6(1):30-5.

- Siddiqui MF, Saleem S, Badireddi S. Pulmonary Talcosis with Intravenous Drug Abuse. Respiratory Care. Oct 2013, 58 (10) e126-e128; DOI: 10.4187/respcare.02402

- Sporer KA. Acute Heroin Overdose. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999 Apr 6;130(7):584-90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-7-199904060-00019

- Waqas M, Waheed S, Haider Z, Shariff AH. Acute mesenteric ischaemia with infective endocarditis: is there a role for anticoagulation? BMJ Case Reports. 2013;2013:bcr2013009741. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009741.

- Misawa S, Sakano Y, Muraoka A, Yasuda Y, Misawa Y. Septic Embolic Occlusion of the Superior Mesenteric Artery Induced by Mitral Valve Endocarditis. Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Released August 25, 2011, [Advance publication] Released July 08, 2011, Online ISSN 2186-1005, Print ISSN 1341-1098, https://doi.org/10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01598

- Wang CC, Lee CH, Chan CY, Chen HW. Splenic infarction and abscess complicating infective endocarditis. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2009 Oct;27(8):1021.e3-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.028

- Majumdar A, Chowdhary S, Ferreira MAS, Hammond LA, Howie AJ, Lipkin GW, Littler WA. Renal Pathological findings in infective endocarditis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 15, Issue 11, 1 November 2000, Pages 1782–1787, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/15.11.1782

- Palepu A, Cheung S, Montessori V, Woods R, Thompson C. Factors other than the Duke criteria associated with infective endocarditis among injection drug users. Clinical And Investigative Medicine. Medicine Clinique Et Experimentale [serial online]. August 2002;25(4):118-125. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 25, 2017

- Ebright JR, Pieper B. Skin and soft tissue infections in injection drug users. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, Volume 16, Issue 3, 2002, Pages 697-712, ISSN 0891-5520, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5520(02)00017-X.

- Khan F, Mukhtar S, Anjum F, Tripathi B, Sriprasad S, Dickinson IK, Madaan S. Fournier’s Gangrene Associated with Intradermal Injection of Cocaine. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. Volume 10, Issue 4, 2013, Pages 1184-1186, ISSN 1743-6095, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12055.

- Richards JR. Rhabdomyolysis and drugs of abuse. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. Volume 19, Issue 1, 2000, Pages 51-56, ISSN 0736-4679, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00180-3.

- Peterson TC, Pearson C, Zekaj M, Hudson I, Fakhouri G, Vaidya R. Septic Arthritis in Intravenous Drug Abusers: A Historical Comparison of Habits and Pathogens. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Volume 47, Issue 6, 2014, Pages 723-728, ISSN 0736-4679, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.06.059.

- Ross JJ, Shamsuddin H. Sternoclavicular septic arthritis: review of 180 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004 May;83(3):139-48. Issn: 0025-7974 DOI: 10.1097/01.md.0000126761.83417.29

- Irish C, Maxwell R, Dancox M, et al. Skin and Soft Tissue Infections and Vascular Disease among Drug Users, England. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(10):1510-1511. doi:10.3201/eid1310.061196.

- Coughlin PA, Mavor AID. Arterial Consequences of Recreational Drug Use. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. Volume 32, Issue 4, 389 – 396. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.03.003

- Johnson JE, Lucas CE, Ledgerwood AM, Jacobs LA. Infected Venous Pseudoaneurysm. A Complication of Drug Addiction. Arch Surg.1984;119(9):1097–1098. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390210087019

- Berk WA. Electrocardiographic findings in infective endocarditis. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. Volume 6, Issue 2, 1988, Pages 129-132, ISSN 0736-4679, https://doi.org/10.1016/0736-4679(88)90153-9.

- Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. The Lancet. Volume 387, Issue 10021, 2016, Pages 882-893, ISSN 0140-6736, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00067-7.

- Fugitt JB, Puckett ML, Quigley MM, Kerr SM. Necrotizing Fasciitis. RadioGraphics2004 24:5, 1472-1476. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.245035169

- Walker TG. Acute Limb Ischemia. Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. Volume 12, Issue 2, 2009, Pages 117-129, ISSN 1089-2516, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tvir.2009.08.005.

- Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 101, Issue 1, 1 January 2008, Pages 1–12, https://doi-org.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/10.1093/qjmed/hcm100

- Fritz JM, McDonald JR. Osteomyelitis: Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment. The Physician and sports medicine. 2008;36(1):nihpa116823. doi:10.3810/psm.2008.12.11.

- Sadiq MA, Hassan M, Agarwal A, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection. 2015;5:32. doi:10.1186/s12348-015-0063-y.

- Baddour L, Wilson W, Fowler ABV, Rybak ITM, Barsic B, Lockhart P, Gewitz M, Levison M, Bolger A, Steckelberg J, Baltimore R, O’Gara AFP, Taubert K, Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications. Circulation. 2015;132:1435-1486. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

- Bedeir K, Reardon M, Ramlawi B. Infective endocarditis: Perioperative management and surgical principles. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Volume 147, Issue 4, 2014, Pages 1133-1141, ISSN 0022-5223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.022.

- Stawicki SP, Firstenberg MS, Lyaker MR, et al. Septic embolism in the intensive care unit. International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science. 2013;3(1):58-63. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.109423.

- Ghaye B, Trotteur G, Dondelinger R. Multiple pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysms: intrasaccular embolization. European Radiology (1997) 7: 176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003300050130

- Monroe EJ, Tailor TD, McNeeley MF, Lehnert BE. Needle embolism in intravenous drug abuse. Radiology Case Reports. 2012;7(3):714. doi:10.2484/rcr.v7i3.714.

- Fernandez LG. Inferior Vena Caval Thrombosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1933035-overview Accessed: 11/18/17

- Natal BL. Venous air embolism. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/761367-overview Accessed: 11/28/17

- Nores M, Phillips E, Morgenstern L, Hiatt J. The clinical spectrum of splenic infarction. The American Surgeon [serial online]. February 1998;64(2):182-188. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 29, 2017.

- Zakaria R, Forsyth V, Rosenbaum T. A rare case of renal infarction caused by infective endocarditis. Nature Reviews Urology. 2009 Oct;6(10):568-72. DOI: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.176

- Antopolsky M, Simanovsky N, Stalnikowicz R, Salameh S, Hiller N. Renal infarction in the ED: 10-year experience and review of the literature. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Volume 30, Issue 7, 2012, Pages 1055-1060, ISSN 0735-6757, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2011.06.041.

- Mertz D, Khanlari B, Viktorin N, Battega M, Fluckiger U. Less than 28 Days of Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment Is Sufficient for Suppurative Thrombophlebitis in Injection Drug Users. Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 46, Issue 5, 1 March 2008, Pages 741–744, https://doi-org.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/10.1086/527445

- Hussain M, Roche-Nagle G. Infected pseudoaneurysm of the superficial femoral artery in a patient with Salmonella enteritidis. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology. 2013;24(1):e24-e25.

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. The American Journal of Medicine, Volume 96, Issue 3, 200 – 209. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(94)90143-0

- Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. Proposed Modifications to the Duke Criteria for the Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 30, Issue 4, 1 April 2000, Pages 633–638, https://doi.org/10.1086/313753