Authors: Christopher Winstead-Derlega, MD, MPH (EM Resident Physician, Stanford Emergency Medicine Residency) and Kathy Staats, MD (EM and EMS Attending Physician, Stanford Department of Emergency Medicine) // Reviewed by: Cynthia Santos, MD (@CynthiaSantosMD, Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine, Medical Toxicology, Addiction Medicine, Rutgers NJMS); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case:

A 21-year-old female presents to the ED with two days of epigastric abdominal pain and persistent nausea and vomiting. On exam she is actively retching into an emesis bag. She is afebrile, tachycardic to 118, normotensive, and breathing 22 times a minute. Her friend reports she takes numerous hot showers throughout the day and continues to smoke cannabis daily.

Background

Cannabis has been used as medicine for centuries. Recently, cannabis has been used to alleviate multiple symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and pain, as well as for treating refractory seizures. The use of medical and recreational marijuana has increased as legal and prescribing restrictions have lessened. States where medical and recreational legalization have occurred are witnessing increased rates of cannabis use and subsequently cannabis related emergency department visits (1). Cannabis intoxication has been associated with anxiety, respiratory depression, and rarely cardiovascular events (emdocs). Some chronic users experience the debilitating symptoms of cyclic nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Cannabis is often used in cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) and chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting due to its antiemetic properties. Paradoxically, hyperemesis as a result of chronic cannabis use has led to the recognition of a new disorder called cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS). CHS first described in an Australian case series in 2004, is the syndromic clustering of nausea, cyclic vomiting and abdominal pain, often relieved with hot showers (emdocs) (2,3,4,6,11). Symptoms are often seen in chronic users with daily to near-daily exposure to cannabis. Many users mistakenly increase consumption assuming that intoxication will relieve symptoms. Thus far only total cannabis cessation has been found to be effective for elimination of symptoms (5,15,16). A recent study from Colorado found CHS from both inhaled and edible forms of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), with higher rates in inhaled forms (1). In addition, there are a limited number of case of reports (n=3) describing synthetic cannabinoid (emdocs) induced CHS (22).

Several theories exist about the cause of this syndrome, including pesticides on marijuana plants, however most believe it is due to the increased potency of THC with advancements in the cultivation of the marijuana plant. Some speculate that chronic high potency THC in genetically predisposed individuals causes differential degrees of cannabinoid receptor downregulation and autonomic dysregulation which can lead to nausea and vomiting (2, 5, 14, 24). Cannabis may have a biphasic mechanism of action, where at lower or less frequent doses it has anti‐emetic effects but at higher or more chronic doses it acts as a pro-emetic.

The prevalence of these symptoms is unknown as many patients are misdiagnosed and many likely do not present to health care facilities. One large urban academic emergency department in Colorado, where cannabis has been legalized, saw 30.7% of cannabis attributed visits related to gastrointestinal symptoms (1).

Pathophysiology

Cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 are the main receptors responsible for THC’s effects on the body (3). Some authors postulate the cannabinoid receptors in the medulla allow for the antiemetic properties of THC, while the cannabinoid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract are suspected to be the source of symptoms due to dysregulation (4,14). Others believe the TRPV1 receptor (transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1), which is activated by marijuana, capsaicin and heat, is altered by chronic marijuana use, and responsible for CHS (8). Both endogenous and exogenous cannabinoids act as agonists for TRPV1.

As most patients with CHS present to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain, patients often receive extensive evaluations with laboratory testing and imaging, along with opioid and non-opioid medications (5,15). Patients suffering from CHS commonly return to the ED due to the persistence and severity of symptoms. Early screening for cannabis use can lead to the early recognition of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (emdocs) and assist the patient and clinician to avoid unnecessary ED visits, diagnostics, pharmaceuticals, and admissions (17).

Diagnosis

While no diagnostic criteria currently exist for definitive CHS diagnosis, Sorenson et al performed a systematic review and identified major characteristics patients typically display (5):

- History of regular cannabis use (100%)

- Cyclic nausea and vomiting (100%)

- Generalized, diffuse abdominal pain (85.1%)

- Compulsive hot showers with symptom improvement (92.3%)

- Symptoms resolve with marijuana use cessation (92.3%)

- A higher prevelance in males (72.9%)

Often patients will experience three phases of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (3,8):

- The Preemetic or Prodromal Phase:

- Can last for months or years

- Characterized by diffuse abdominal discomfort, feelings of agitation or stress, morning nausea, and fear of vomiting

- May also include autonomic symptoms like flushing, sweating, and increased thirst

- Often have increased use of marijuana to treat these symptoms

- Hyperemetic Phase:

- 24-48 hours

- Multiple episodes of vomiting

- Diffuse, severe abdominal pain

- Recovery Phase:

- Begins with total cessation of cannabis

- Often patients require a bowel regimen, IV fluids, and electrolyte replacement

- Resolution of symptoms may take up to one month

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to note that cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. If it is a patient’s first presentation for nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, other primary etiologies such as gallbladder or intestinal disease, intoxications, or surgical emergencies should be considered, before a diagnosis of CHS is solidified. Patients with repeat presentations for nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, with chronic marijuana use, negative previous evaluations and no history of diabetes, allow CHS to be higher on the differential diagnosis.

Most Common Complications of CHS:

- Electrolyte abnormalities (most commonly low potassium)

- Dehydration or acute kidney injury

- Muscle cramping or spasms

Documented Life-Threatening Complications of CHS:

- Pneumomediastinum from a ruptured esophagus

- Electrolyte derangement causing seizures, arrhythmias

Treatment

Research on the treatment of CHS is limited. Clinicians often treat symptoms of CHS including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain with traditional pharmaceuticals. All patients with suspected CHS should be offered cannabis cessation counseling, resources, and follow up (15). Only total cannabis cessation has been found to be effective for preventing and eliminating symptoms (5,15,16).

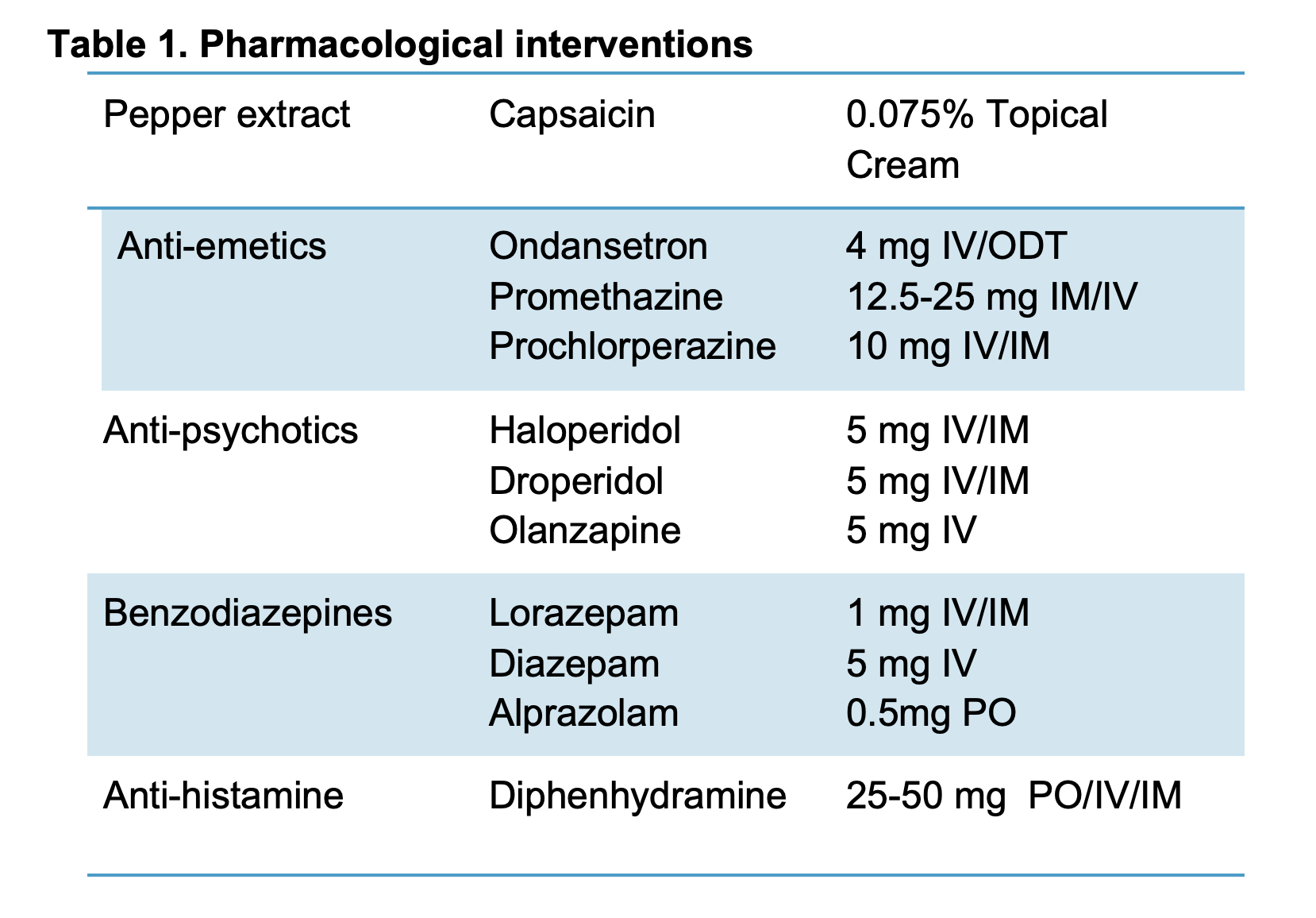

Numerous traditional and nontraditional approaches have been used including dopamine antagonists, antihistamines, serotonin antagonists, antipsychotics, and topical capsaicin (4,5,8,11,13,18,20). (Table 1).

Capsaicin

Capsaicin, the active ingredient of chili peppers, has been promoted as a treatment for CHS initially based on patients’ successes with hot showers. Several case series and retrospective reviews have shown benefits in adolescents (9) and adults (10). The cream is applied to the fatty areas of the backs of the arms and abdomen (4), and causes a sensation of warmth or burning. It comes in various concentrations between 0.025% to 0.15%, and is applied to the shoulders, extensor surface of the arms, back or abdomen up to three times daily. (Table 2.)

One proposed mechanism behind the relief of capsaicin is its ability to transiently activate TRPV1, previously down regulated during chronic exposure to cannabinoids. (8, 12). Capsaicin along with warm stimulation such as hot showers, activate TRPV1, which may explain the relief CHS patients receive from compulsive showering. Capsaicin is cheap, with few side effects, and is often successful for treating patients who have not received other medications for their CHS before (4).

Benzodiazepines

One or a combination of the following medications can be successful for acute treatment of CHS symptoms. A systematic review of pharmacological treatments for CHS found evidence to support benzodiazepines such as lorazepam and diazepam (20). These medications work through GABA receptor agonism, thus neurotransmitter inhibition, causing sedation, anxiolysis, and muscle relaxation.

Antipsychotics and Tricyclic Antidepressants

Previously reserved for agitated patients, haloperidol has been used off-label for postoperative nausea and has been often used successfully to treat CHS. Several case reports describe complete relief of symptoms from haloperidol (18,19). The drug is a butyrophenone antipsychotic with high affinity dopamine antagonism at the D2 receptor in the CNS. Currently a randomized crossover clinical trial is completing research comparing haloperidol and ondansetron (21). Likely not a medication to start in the emergency department, tricyclic antidepressants have demonstrated effectiveness in cyclic vomiting syndrome and CHS (20,21). It is believed to be related to serotonin reuptake inhibition in addition to antihistamine effects (23). Unfortunately the above medications are not without risk.While capsaicin adverse reactions are topical and non-life-threatening, some of the listed medications can cause significant side-effects including Qt prolongation and arrhythmias, respiratory depression, and extreme feelings of anxiety.

Future Research

We know emergency departments are witnessing increasing incidents of cannabis related pathology (1). A significant group of these patients suffer from CHS, and many remain undiagnosed. These patients often receive expansive diagnostic workups, numerous pharmacological interventions, and frequently require observation or hospitalization. A recent systematic review found poor quality of evidence beyond case reports many pharmaceuticals (20) and no randomized trials have been completed. While research continues to be in its early stages, the early recognition of CHS and treatment may prevent costly work ups, admissions and prolonged symptoms of patients suffering from CHS (17).

Pearls

- Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome is increasing in frequency in the United States.

- CHS is characterized by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and chronic cannabis use.

- Consider CHS diagnosis in patients with recurrent presentations and negative abdominal pain work-ups.

- Avoid opiates for CHS treatment.

- Consider capsaicin cream, benzodiazepines, antiemetics and antipsychotics for treatment of CHS.

References/Further Reading

- Monte AA, Shelton SK, Mills E, Saben J, Hopkinson A, Sonn B, et al. Acute Illness Associated With Cannabis Use, by Route of Exposure: An Observational Study. Ann Intern Med. [Epub ahead of print]

- Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. 2004;53(11):1566–1570. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.036350

- Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(4):241–249.

- Lapoint J, Meyer S, Yu CK, et al. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Public Health Implications and a Novel Model Treatment Guideline. West J Emerg Med. 2017;19(2):380–386. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.11.36368

- Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment-a Systematic Review. J Med Toxicol. 2016;13(1):71–87. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z

- Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: a case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Feb;87(2):114-9. Doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.10.005. PubMed PMID: 22305024; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3538402.

- Pélissier F, Claudet I, Gandia-Mailly P, Benyamina A, Franchitto N. Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome in the Emergency Department: How Can a Specialized Addiction Team Be Useful? A Pilot Study. J Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;51(5):544-551. Doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.009. Epub 2016 Jul 30. PubMed PMID: 27485997.

- Moon AM, Buckley SA, Mark NM. Successful Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome with Topical Capsaicin. ACG Case Rep J. 2018;5:e3. Published 2018 Jan 3. doi:10.14309/crj.2018.3

- Graham J, Barberio M, Wang GS. Capsaicin Cream for Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome in Adolescents: A Case Series. Pediatrics. 2017 Dec;140(6). pii: e20163795. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3795. Epub 2017 Nov 9. PubMed PMID:29122973.

- Dezieck L, Hafez Z, Conicella A, Blohm E, O’Connor MJ, Schwarz ES, Mullins ME. Resolution of cannabis hyperemesis syndrome with topical capsaicin in the emergency department: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017 Sep;55(8):908-913. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1324166. Epub 2017 May 11. PubMed PMID: 28494183.

- Pergolizzi Jr. J, V, LeQuang J, A, Bisney J, F: Cannabinoid Hyperemesis. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids 2018;1:73-95. doi: 10.1159/000494992

- Yang F, Zheng J. Understand spiciness: mechanism of TRPV1 channel activation by capsaicin. Protein Cell. 2017;8(3):169–177. doi:10.1007/s13238-016-0353-7

- McConachie, S. M., Caputo, R. A., Wilhelm, S. M., & Kale-Pradhan, P. B. Efficacy of Capsaicin for the Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2019. https://doi.org/1177/1060028019852601

- Smith, T. N., Walsh, A., Forest, C. P. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: An unrecognized cause of nausea and vomiting. 2019 Apr;23(4):30-34

- Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, Jelley MJ. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011;104(9):659–64.

- Soriano-Co M, Batke M, Cappell MS. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: a report of eight cases in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(11):3113–9.

- Zimmer DI, McCauley R, Konanki V, et al. Emergency Department and Radiological Cost of Delayed Diagnosis of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis. J Addict. 2019;2019:1307345. Published 2019 Jan 1. doi:10.1155/2019/1307345

- Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun;31(6):1003.e5-6.

- Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol, a Novel Treatment for Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome. Am J Ther. 2017 Jan/Feb;24(1):e64-e67.

- Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR, Moulin AK. Pharmacologic Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Pharmacotherapy. 2017 Jun;37(6):725-734.

- Namin F, Patel J, Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Foran P, Esmaeili P, McCallum R. Clinical, psychiatric and manometric profile of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults and response to tricyclic therapy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007 Mar;19(3):196-202.

- Bick BL, Szostek JH, Mangan TF. Synthetic cannabinoid leading to cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Aug;89(8):1168-9.

- ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03056482

- Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: Cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2019 Jun; 31(Suppl 2):e13606.

#FOAMed

- http://www.emdocs.net/updates-cannabis-use-dangers-u-s/

- http://www.emdocs.net/cyclic-vomiting-syndrome-pearls-and-pitfalls/

- http://www.emdocs.net/synthetic-cannabinoids/

- https://www.aliem.com/2017/11/trick-trade-treatment-cannabinoid-hyperemesis/

- https://www.emrap.org/episode/readysetpause/capsaicinfor

2 thoughts on “More Than a Hot Shower – Treatment for Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS)”

I use haldol (depending on the size of the patient 3-5mg IV) consistently with great results. I have seen Ativan work (if there is a reason not to use haldol) but it has to be a good dose, for example 2mg IV). PO medications in my experience are a waste of time, and I would avoid stemetil or the other anti-emetics. They are risky, because when they fail (and they will) you have a more significant QT risk, since you’ve already given a QT prolonging med.

Pingback: October ’19 Asynchronous Learning – Lakeland Health EM Blog