Authors: Stephanie Costa, MD (EM Resident Physician, Reading, PA), Courtney Cassella, MD (EM Attending Physician, Reading, PA) // Reviewed by: Skyler Lentz, MD (@sklyerlentz); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK)

Case

A 40 year-old patient presents with increasing abdominal pain and a new fever. She initially presented to the Emergency Department five days prior for upper abdominal pain. The initial workup showed stable vital signs, mildly elevated lipase, and an unremarkable right upper quadrant ultrasound. The patient was diagnosed with gastroenteritis and discharged home with primary care follow up. She now returns to the Emergency Department five days later with increased abdominal pain and feeling overall unwell.

Vital signs: BP 105/70, HR 95, T 37.9, RR 20, SpO2 100% RA

Exam reveals a moderately distressed patient, with severe epigastric pain to mild palpation of the abdomen.

Today, she is noted to have markedly elevated serum lipase. CT with IV contrast was performed, with results concerning for necrotizing pancreatitis.

Background

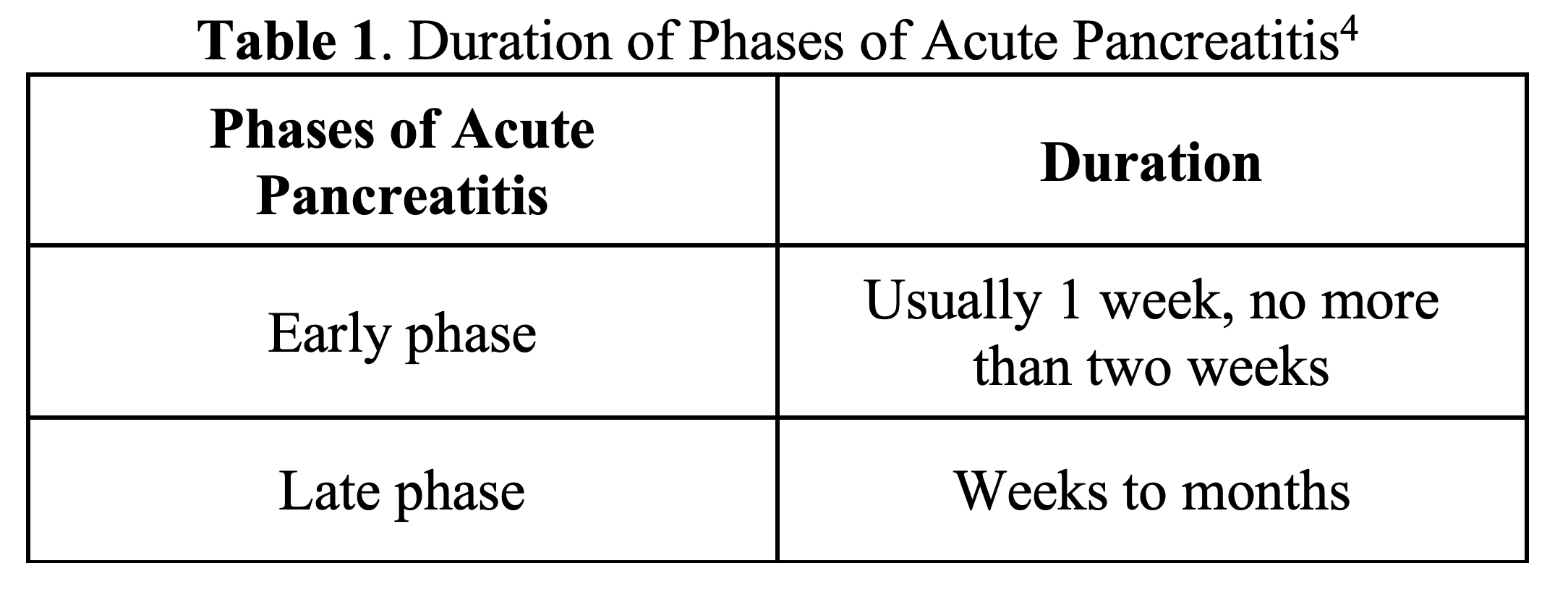

Acute pancreatitis requires at least two of the following criteria for diagnosis: (1) upper abdominal pain; (2) elevated pancreatic enzymes at least 3 times the upper limit of normal; and/or (3) imaging findings 1,2,3,4. Acute pancreatitis has different phases and different levels of severity (Tables 1 and 2). The early phase involves SIRs with or without organ failure5. Late phase of acute pancreatitis involves local complications4, such as acute necrotic collections and walled off necrosis, which occurs in 5-10% cases with a majority of those cases involving peripancreatic and pancreatic tissues4,6. However, some literature quotes as high as 40% of patients will develop acute necrotic pancreatic collections7. Although both are considered local complications, acute peripancreatic fluid collections have a homogenous appearance without encapsulation on imaging, whereas necrotic collections have a heterogeneous appearance without encapsulation on imaging4.

Presentation and Evaluation

Although few cases of pancreatitis result in necrotizing consequences, this sequela should be suspected when abdominal pain does not resolve, pancreatic enzymes are increasing, signs of sepsis with or without organ dysfunction, and/or unexplained fever4,8. Signs of sepsis includes systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria of temperature <36°C or >38°C, heart rate >90 beats per minute, respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute, leukocytosis or leukopenia9.

On imaging, suspect necrosis if a non-enhancing area within the pancreas is visualized2,4. For example, Figure 1 displays peripancreatic fluid and pancreatic edema in a case of necrotizing pancreatitis10. Furthermore, the necrotic region is considered infected when there are fluid collections with gas present and confirmed with collection aspiration2,8. It is important to have a high suspicion for infected necrotizing pancreatitis, as this is associated with increased mortality4.

When clinical and lab findings support the diagnosis of pancreatitis, the initial emergency department evaluation should include abdominal ultrasound to evaluate for etiology such as biliary disease11. However, alternative imaging by CT or MRI should be considered when the lipase is normal, other lab abnormalities are present, SIRS criteria are met, and/or the symptoms have been present for greater than 48 hours11. In these cases, one should decide between CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast or MRI abdomen without and with IV contrast with MRCP11. If the patient has known necrotizing pancreatitis, where there is clinical deterioration, hemoglobin drop, increased WBC or vital sign changes, the imaging test of choice is CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast11.

Other indications for imaging with CT in suspected acute pancreatitis includes: pancreatitis is only one of probable etiologies in the differential diagnosis, clinical picture requires severity confirmation, deterioration or failure of conservative treatment1. However, there is a pitfall to ordering imaging as timing is important for the imaging to be diagnostic of necrotizing pancreatitis. CT imaging for high yield imaging, especially for necrotizing pancreatitis, needs to be performed 72 hours after symptom onset1,8.

For more information on the presentation, diagnosis, and management of pancreatitis, please follow the link for “Pancreatitis: Pearls & Pitfalls” 12 http://www.emdocs.net/pancreatitis-pearls-pitfalls/

Management

Emergency Department management for all cases of pancreatitis is centered around supportive measures and identifying complications. Patients require early fluid resuscitation, preferably with Lactate Ringer’s1, electrolyte repletion and intake/output monitoring8. Fluids are of the utmost importance as SIRS and organ failure are decreased with early fluid intervention1 to maintain blood pressure and organ perfusion6,8. An additional tenet of care includes pain control8.

Pharmaceutical intervention, such as octreotide and glucagon, is not recommended based on limited data to improve short-term mortality13.

Despite the morbidity of infected necrotizing pancreatitis, prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended1 as there is no evidence-based advantage to prophylactic antibiotic usage5. Antibiotics, such as metronidazole, quinolones and carbapenems, may be used for infected pancreatic necrosis, but the evidence is low quality5. Another study noted that if there is concern for infection development, imipenem may be helpful to decrease infection rates, but not mortality14. Antibiotics should be started in cases of infected necrosis or if the patient is deteriorating, failing to improve or once culture of the collection is obtained5.

Although sterile necrotizing pancreatitis can be treated with conservative management1,6, intervention would be needed if the necrosis caused a mass effect or obstruction to GI structures, persistent symptoms or pancreatic duct damage1. Early consultation to interventional radiology / GI or surgery may be prudent in cases where there is necrotizing disease. Particularly, if a patient develops necrotizing pancreatitis and is clinically deteriorating, or has non-resolving organ failure after acute pancreatitis, the patient may require interventions such as percutaneous catheter drainage, endoscopic drainage/necrosectomy or open/minimally invasive necrosectomy1. Intervention is preferred after the necrotic area has become “walled off”, at least four weeks after presentation1.

Prognosis

There is consensus that the morbidity and mortality of necrotizing pancreatitis is high6,15. According to a Cochrane review of 8 RCTs with low quality evidence secondary to high bias risk and small trials, the short-term death rate of necrotizing pancreatitis is 30%3. Sepsis secondary to infected necrosis leads to 80% of deaths in patients diagnose with acute pancreatitis16.

In a single center retrospective study of 77 patients, 61% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis required only conservative management such as fluid and electrolyte management, oxygen support, analgesia, and enteral feeding17. However the study had an overall mortality rate in 10.38% in patients diagnosed with necrotizing pancreatitis17. High morbidity in the form of hemorrhage, bowel obstruction, fistula formation and long hospitalizations were also noted in the study17.

Disposition

Disposition of patients with pancreatitis depends on the severity of the disease and the supportive care required by the patient. When patients have mild pancreatitis, most patients have self-limited disease with little to no long-term consequences15. Although in many cases patients are admitted, if the patient has mild disease, can maintain hydration status, and pain is well controlled, they may be able to be discharged.

If there are other etiologies to the acute pancreatitis, those need to be addressed. For example, if there is biliary obstruction, the patient needs urgent ERCP6 and would require hospital admission.

Admission to higher level of care for sterile necrotizing pancreatitis is dependent largely on patient condition as many patients with necrotizing disease have higher mortality and may compensate quickly. The Revised Atlanta Criteria (Table 2) helps to classify the severity of acute pancreatitis, with patients who present with necrotizing pancreatitis falling into either moderately severe acute pancreatitis or severe acute pancreatitis, depending on the presence of persistent organ failure4.

Patients with septic necrotizing pancreatitis should likely be admitted to a higher level of care, such as the ICU if organ failure is present18, given rate of morbidity and mortality. In addition, as mentioned above, interventional radiology or GI consultation early may be beneficial.

Key Points

- If a patient was previously diagnosed with pancreatitis and is now presenting with clinical worsening, consider necrotizing pancreatitis.

- CT or MRI with contrast at least 3 days after symptom presentation will give highest yield images for necrotizing pancreatitis diagnosis.

- Heterogeneous fluid collections and gas within necrotic pancreatic collections may indicate infected necrotizing pancreatitis.

- Mainstay of management is targeted fluid resuscitation, electrolyte repletion, and analgesia. Vigilance for development of complications and organ failure is paramount.

- Antibiotics should not be routinely used for sterile necrotizing pancreatitis, but if there is suspicion for infection development, metronidazole, quinolones and carbapenems, specifically imipenem, may be used, but there is limited evidence. Antibiotic usage should be guided by aspiration cultures.

Case Resolution

The patient was admitted for fluid resuscitation, analgesia and further supportive care. Enteral nutrition was restarted once the abdominal pain began to subside. She was given discharge instructions for dietary and lifestyle changes to decrease her risk of further pancreatic irritation, such as stopping alcohol intake and manage her cholesterol12. She has a follow up appointment with interventional radiology in four weeks to determine if percutaneous drainage is required.

References/ Further Reading

- IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis.Pancreatology. Jul-Aug 2013;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15. doi:10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063

- Busireddy KK, AlObaidy M, Ramalho M, et al. Pancreatitis-imaging approach. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 2014;5(3):252-270. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.252

- Gurusamy KS, Belgaumkar AP, Haswell A, Pereira SP, Davidson BR. Interventions for necrotising pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;(4)doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011383.pub2

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus.Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS. American College of Gastroenterology Guideline: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:1400-1415. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218

- Boumitri C, Brown E, Kahaleh M. Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Current Management and Therapies.Clinical Endoscopy. 2017;50(4):357-365. doi:10.5946/ce.2016.152

- Zerem E. Treatment of severe acute pancreatitis and its complications. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(38):13879-13892. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13879

- Trikudanathan G, Wolbrink DRJ, van Santvoort HC, Mallery S, Freeman M, Besselink MG. Current Concepts in Severe Acute and Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach.Gastroenterology. May 2019;156(7):1994-2007.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.269

- Mahapatra S, Heffner AC. Septic Shock (Sepsis). StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Niknejad MT. Necrotizing pancreatitis. Updated August 14, 2019. Accessed October 12, 2020.https://radiopaedia.org/cases/necrotizing-pancreatitis-1?lang=us

- Porter KK, Zaheer A, Kamel IR, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Pancreatitis.J Am Coll Radiol. Nov 2019;16(11s):S316-s330. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2019.05.017

- Waller A. Pancreatitis: Pearls & Pitfalls. emDocs. Accessed September 10, 2020. http://www.emdocs.net/pancreatitis-pearls-pitfalls/

- Moggia E, Koti R, Belgaumkar AP, et al. Pharmacological interventions for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews. 2017;(4)CD011384. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011384.pub2

- Villatoro E, Mulla M, Larvin M. Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews. 2010;(5)CD002941. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002941.pub3

- Bendersky VA, Mallipeddi MK, Perez A, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: challenges and solutions. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 2016;9:345-350. doi:10.2147/CEG.S99824

- 16. Koo BC, Chinogureyi A, Shaw AS. Imaging acute pancreatitis. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(986):104-112. doi:10.1259/bjr/13359269

- 17. Aparna D, Kumar S, Kamalkumar S. Mortality and morbidity in necrotizing pancreatitis managed on principles of step-up approach: 7 years experience from a single surgical unit. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2017;9(10):200-208. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v9.i10.200

- Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2019;14(27)doi:10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0