Authors: Darren Cuthbert, MD, MPH (EM Resident Physician at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital) and Joshua Bucher, MD (EM Attending Physician, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital) // Edited by: Erica Simon, DO, MHA (@E_M_Simon) and Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital)

Emergency physicians encounter penetrating trauma on a regular basis. Beyond Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols, the assessment of a patient presenting with a penetrating wound requires careful thought and thorough examination. If it’s been a while since you’ve reviewed the basics, let’s take a minute to work through a few cases and discuss the pearls and pitfalls for the management of penetrating injuries.

Case I: A 69-year-old intoxicated male presents via EMS with what appears to be a penetrating wound to the neck. The patient is in no obvious distress. Speaking clearly to the room, he reports robbery by an unknown assailant, and a singular knife wound to his neck. Upon examination the patient has clear breath sounds bilaterally. His pulses are equal and bounding, and his initial vital signs are within normal limits. Secondary survey is remarkable for a 3 cm superficial laceration to the lateral aspect of the left neck, localized to zone II. There is no evidence of a rapidly expanding hematoma or pulsatile bleeding. There is no violation of the platysma.

Case II: A 20-year-old female presents to the trauma bay intubated, ventilated, and sedated. EMS details arriving on scene to find the young women diaphoretic, in respiratory distress, and covered in blood. While holding her chest, she reported her fiancé as having inflicted a knife wound to her upper abdomen. Given the patient’s appearance, EMS performed intubation on scene. Emergency room evaluation revealed diminished breath sounds on the left. Tube thoracostomy was performed and resuscitation initiated (2U PRBCs), however, the patient remained tachycardic and hypotensive.

Case III: During an early morning shift, you receive a phone call regarding a patient en route from scene: 32-year-old male involved in an altercation with a machete; intubated on scene secondary to altered mental status, wounds localized to the head and left upper extremity. Upon arrival, primary and secondary survey reveal a hemodynamically stable male with a 7 cm gaping wound localized to the posterior occiput (hemostatic), and a 3 cm gaping wound localized to the left forearm (hemostatic).

Case IV: A 21-year-old male presents to emergency triage with the chief complaint of injury to the neck and armpit. The patient, in no acute distress, speaks in clear sentences while detailing his recent fall over a nail gun, with subsequent gun discharge and trauma to his neck and chest. As he was “feeling fine,” the patient reports having removed two nails prior to seeking treatment. Emergency department primary and secondary surveys are significant for puncture wounds to the anterior midline neck (zone III), and left midaxillary line at the level of T4. Crepitus is noted on palpation of the left anterior chest wall.

Let’s move on to a review of the fundamentals before we address our cases:

The Head

The initial approach to penetrating head wounds centers on attaining hemostasis. After addressing airway and breathing in a patient with head trauma, direct pressure should be applied to any actively bleeding wound as these injuries (specifically injuries to the highly vascular scalp) may result in hemodynamic instability.1 If hemostasis is not attained following the application of direct pressure, experts advise local wound infiltration with lidocaine with epinephrine, or the ligation, suture, or clamping of visibly damaged vessels.1

The majority of patients with head trauma will required advanced imaging to rule out intracranial pathology and foreign bodies.1-3 If no evidence of foreign body or underlying depressed skull fracture, irrigate wounds thoroughly, explore to the base, and remove any organic material.1,2 If the galea is involved, consideration should be made for repair as failure to do so may lead to frontalis muscle (facial expression) deficit.1

The Face

In patients with penetrating facial trauma, management of the airway if paramount. During assessment pay close attention to voice changes and tachypnea, and evaluate for cyanosis as these are precursors of airway compromise and respiratory demise.1 Facial fractures and active bleeding into the oropharynx increase the level of difficulty when performing endotracheal intubation, therefore equipment preparation is advised (bougie or surgical airway kit). CT scans of the head, facial bones, and neck may be required to evaluate for underlying injuries to the face and surrounding structures of the head and neck.1 For impaled objects, admission is often required for surgical intervention, monitoring, and administration of broad spectrum antibiotics.1

The Neck

Patients with trauma to the neck who present with signs of respiratory compromise, such stridor, expanding hematoma, pulsatile arterial bleeding, bruit/thrill, or altered mental status should be emergently intubated.1,2 After attaining a definitive airway, be prepared to address circulation: exsanguination is the most common cause of death in this patient population.1 Consider placing the patient with a penetrating neck injury in Trendelenburg position to prevent air embolism, while addressing all actively bleeding wounds with direct pressure (caution as excessive force may occlude the carotid arteries).1 Although randomized controlled trials in the setting of penetrating neck trauma are lacking, hemostatic dressings including QuikClot, Combat Gauze, and HemCon are commonly utilized in the emergency department and have demonstrated affectivity in the attainment of hemostasis in the setting of life threatening hemorrhage.1 Clamping vessels of the neck is not recommended in the emergency department, as anatomic structures are not easily identified upon visual inspection, and probing of a neck wound is not advised.1,3 If active bleeding continues despite direct pressure and the use of a hemostatic dressing, consider mechanical tamponade with a Foley catheter: insert the catheter into the tract of the wound and inflate until bleeding ceases.1,2 If these attempts are unsuccessful, emergent surgical intervention is required.

Definitive management of wounds to the neck historically centers upon patient presentation and zone classification (see Figure 1). Patients experiencing hemorrhagic shock, airway obstruction, air discharge from their wound, active pulsatile blood flow, massive hemoptysis, and uncontrolled bleeding (the hard signs of neck trauma), regardless of zone classification, require surgical evaluation and treatment.1 Hemodynamically unstable patients with Zone I injury may require ED thoracotomy.1

- Zone I => sternal notch to cricoid cartilage

- CT angiography, endoscopy, and bronchoscopy are indicated for evaluation.1,2,5

- Note: suspect hemothorax or pneumothorax in patients presenting with dyspnea or absent breath sounds (20% of patients with penetrating neck trauma have a pneumothorax or hemothorax on further examination1).

- Zone II => cricoid cartilage to angle of the mandible

- Violation of the platysma mandates surgical exploration.1

- Zone III => angle of the mandible and above

- CT angiography and endoscopy indicated for evaluation.1,2,5

- CT angiography, endoscopy, and bronchoscopy are indicated for evaluation.1,2,5

Note: Importantly, esophageal injuries occur in up to 9% of patients with penetrating neck trauma. As the sensitivity of CT in the detection of early esophageal injury is reported as 53%,6 patients with esophageal perforation most commonly present with sepsis secondary to mediastinitis.1 If concern for esophageal perforation exists: initiate antibiotic therapy, obtain surgical consultation, and perform esophagograpy with a water-soluble contrast material.1

A cervical collar may prevent adequate examination and stabilization of the patient with a penetrating neck injury. As vertebral and spinal cord injuries are rare in the setting of isolated penetrating neck trauma, current guidelines recommend against c-spine immobilization.1,5

The Thorax

Thoracic trauma is the third leading cause of traumatic death in the United States.2 Injury to the heart or major vessels should be assumed in all patients presenting with injury localized to the “cardiac box” – i.e. the area bordered by the sternal notch, bilateral nipples, and xiphoid process. Patients experiencing penetrating trauma at this anatomic locale may suffer right ventricular injury (most anterior mediastinal structure) and subsequent tamponade or exsanguination.1-3 On examination, the most reliable sign of developing tamponade physiology is a narrowed pulse pressure (Beck’s Triad is present in < 10% of cases).1

The FAST is a useful tool for evaluating cardiac injury and tamponade. Patients with tamponade secondary to cardiac trauma may require emergent pericardiocentesis prior to operative repair.1 Individuals who are hemodynamically unstable or become pulseless upon ED evaluation frequently undergo emergent thoracotomy.1

Penetrating chest trauma that violates the pleura may also result in a pneumothorax or hemothorax.1,2,4 Pneumothorax should be presumed in patients with significant subcutaneous emphysema on examination.1,2,7 An EFAST may quickly identify the presence of a pneumothorax or hemothorax.1 All patients with evidence of tension physiology (hypotension, hypoxia, absent breath sounds, and tracheal deviation) should undergo needle decompression and subsequent thoracostomy.1 All patients with an identified hemothorax require thoracostomy to avoid the sequelae of fibrosis and empyema.1 An immediate indication for surgical intervention (versus ED thoracotomy) in the setting of a hemothorax is the release of greater than 1,500 mL of blood upon initial placement of a chest tube, or persistent drainage of at least 150-200 mL of blood for greater than 2 hours after chest tube placement.1,7

The Abdomen

Hemodynamically unstable patients with penetrating trauma to the abdomen, or those who present with frank evisceration, require exploratory laparotomy.1 Hemodynamically stable patients with a positive FAST are appropriate for advanced imaging (CT). If there is question regarding fascial penetration, bedside wound exploration should only be undertaken by a specialist (general/trauma surgeon).1,2

The Extremities

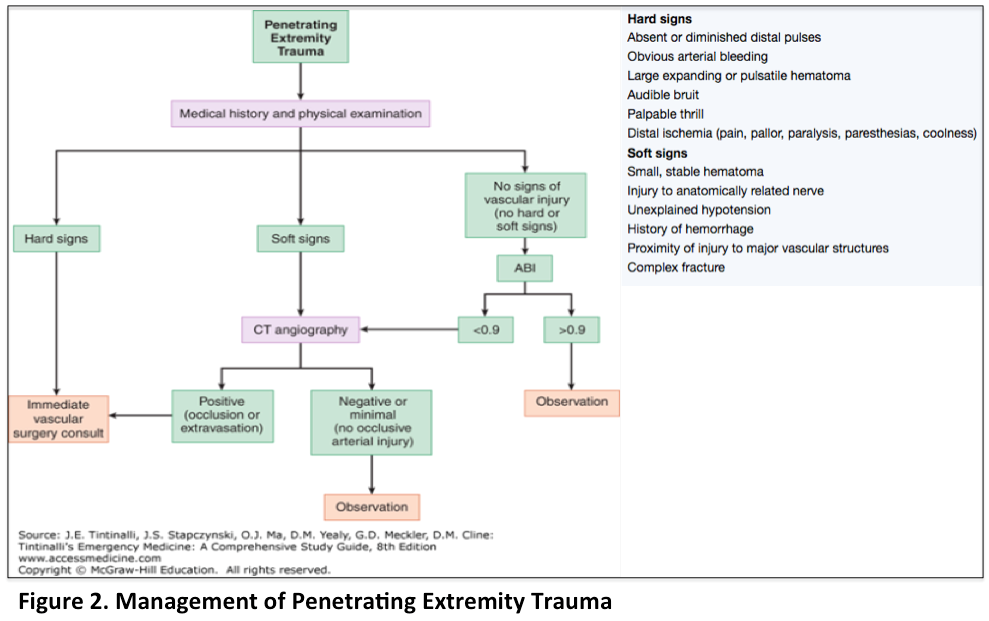

Similar to bleeding at other anatomic locations, initial management of extremity trauma concentrates on hemostasis through the application of direct pressure or pressure dressings.1 Tourniquet application should be considered in the setting of life threatening hemorrhage.1 In this patient population, the secondary survey should focus on the evaluation of injury to vascular, neurologic, and musculoskeletal structures.1 Similar to neck injuries, penetrating trauma localized to the extremities require attention to hard and soft signs (Figure 2).1 Hard signs which require surgical management are absent or diminished pulses, obvious arterial bleeding, expanding hematoma or pulsatile bleeding, audible bruit, palpable thrill, or distal ischemia.1 Soft signs requiring additional diagnostic evaluation include small hematomas, nerve injury, unexplained hypotension, history of hemorrhage, proximal vascular damage without hypotension, and complex fracture.1 As with neck injuries, avoid clamping vessels in the extremities as this intervention carries high risk of arterial or nerve damage.1

Final Words

It is important to perform a thorough secondary examination of all patients presenting with a penetrating injury. Wounds hidden in skin folds, the axilla, or nape of the neck are easily missed. All impaled objects that remain in place upon arrival to the ED should not be removed, but rather stabilized.1,4

How should our patients in the cases be managed?

Case I: The patient is stable and does not require emergent surgical intervention as his wound is localized to zone II and does not violate the platysma. He is likely to undergo advanced imaging given his intoxication.

Case II: The patient should be taken to the operating room for diagnostic laparotomy given her persistent hypotension despite resuscitation.

Case III: The patient is hemodynamically stable with gaping, hemostatic wounds to the skull and forearm. Given his altered mental status and absence of vital sign abnormalities, increased ICP should be assumed: head of bed elevated 30°, hyperventilated to a pCO2 of 35, and 3% NS delivered (+/- mannitol administered per institutional policy or in consultation with trauma surgery/neurosurgery). CT imaging subsequently revealed a large epidural hematoma with 3 mm of midline shift.

Case IV: The patient’s chest X-ray was notable for subcutaneous emphysema, and CT of the chest revealed significant subcutaneous emphysema with a large apical pneumothorax. A left sided chest tube was placed and the patient was admitted for further evaluation with bronchoscopy and EGD.

Summary

- ED management of a patient with a penetrating injury begins with addressing the ABCs.

- The first step in addressing active bleeding is the application of direct pressure.

- Patients with head wounds commonly undergo advanced imaging to rule out foreign body and underlying trauma.

- Hemorrhagic shock, airway obstruction, air discharge from a wound, active pulsatile blood flow, massive hemoptysis, and uncontrolled bleeding in patients with neck injuries mandate immediate surgical intervention.

- Assume cardiac and great vessel injury in all patients with trauma to the cardiac box.

- Hemodynamically unstable patients with abdominal trauma require operative intervention.

- Patients with penetrating injuries to the extremities with absent or diminished pulses, obvious arterial bleeding, expanding hematoma or pulsatile bleeding, audible bruit, palpable thrill, or distal ischemia require operative intervention.

References / Further Reading

- Tintinalli, J.E., Stapczynski, O.J., Ma, D.M., Meckler, G.D., Cline, D.M. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8th www.accessmedicine.com. 2015.

- LoCicero, J., Mattox, K.L. Epidemiology of Chest Trauma. Surgical Clinics of North America. 69(1): 15-9. 1989. PMID: 2911786.

- Sormann, P., Wutzler, S., Sommer, K., Marzi, I., Lustenberger, T., Walcher, F. Gunshot and Stab Wounds: Diagnosis and Treatment in the Emergency Room. Emergency and Rescue Medicine. 2(1-9). 2016. DOI: 10.1007/s10049-016-0162-9

- Daya, N.P., Liversage, H.L. Penetrating Stab Wound Injuries to the Face. Europe PMC. 2004. 59(2):55-59. PMID: 15181702.

- White, C.C., Domeier, R.M., Millin, M.G. National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. EMS Spinal Precautions and the Use of the Long Backboard. Available from: http://www.naemsp.org/Documents/Position%20Papers/EMS%20Spinal%20Precautions%20and%20the%20Use%20of%20the%20Long%20Backboard_Resource%20Document.pdf

- Bothwell N. Acute Management of Pharyngoesophageal Trauma. Ch 30. Department of Defense. Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery Combat Casualty Care in Operation Iraqi freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. Army Borden Institute.

- Mowery, N.T., Gunter O.L., Collier, B.R., Diaz, J.J. Hemothorax and Occult Pneumothorax; Management of. Journal of Trauma. 2011. Feb; 70 (2): 510-8. Available from: https://www.east.org/education/practice-management-guidelines/hemothorax-and-occult-pneumothorax,-management-of