Authors: Aaron Blau, MD (EM Resident Physician, UVM Emergency Medicine) and Richard Bounds, MD (EM Attending Physician / Program Director, University of Vermont Medical Center) // Reviewed by: Mark Ramzy, DO, EMT-P (@MRamzyDO); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 45-year-old male with no known medical history and no previous syncope presents from home with a witnessed syncopal event without trauma. In the ED, his mental status is at baseline, his ECG is unremarkable, and his exam and initial vital signs are normal. He was not exerting himself at the time and does not recall a clear prodrome. He blames “passing out” on doing yard work earlier in the day in the heat, and wants to go home.

Question

For patients presenting with syncope of unknown etiology, who needs to be admitted and who can go home?

Background

Patients with a chief complaint of syncope often present to the ED looking well without symptoms. The history obtained in these syncopal patients often involves a sudden, transient loss of consciousness, followed by spontaneous recovery, and indicates a period of cerebral hypo-perfusion. (1, 2) Syncope accounts for 3-5% of all ED visits, and hospital admission rates range from 1-6%. (3) This variability in admission rates is important, since inpatient evaluations are generally associated with low clinical utility, and hospital costs have been reported to exceed $2.4 million in the US annually. (3)

Emergency providers must maintain a wide differential in cases of sudden loss of consciousness. Some but not all etiologies to consider include seizure, TIA, hypoxia, cataplexy, head injury, and intoxication. A detailed physical and history, including the report of witnesses, should allow clinicians to differentiate from alternative conditions in most cases. (1)

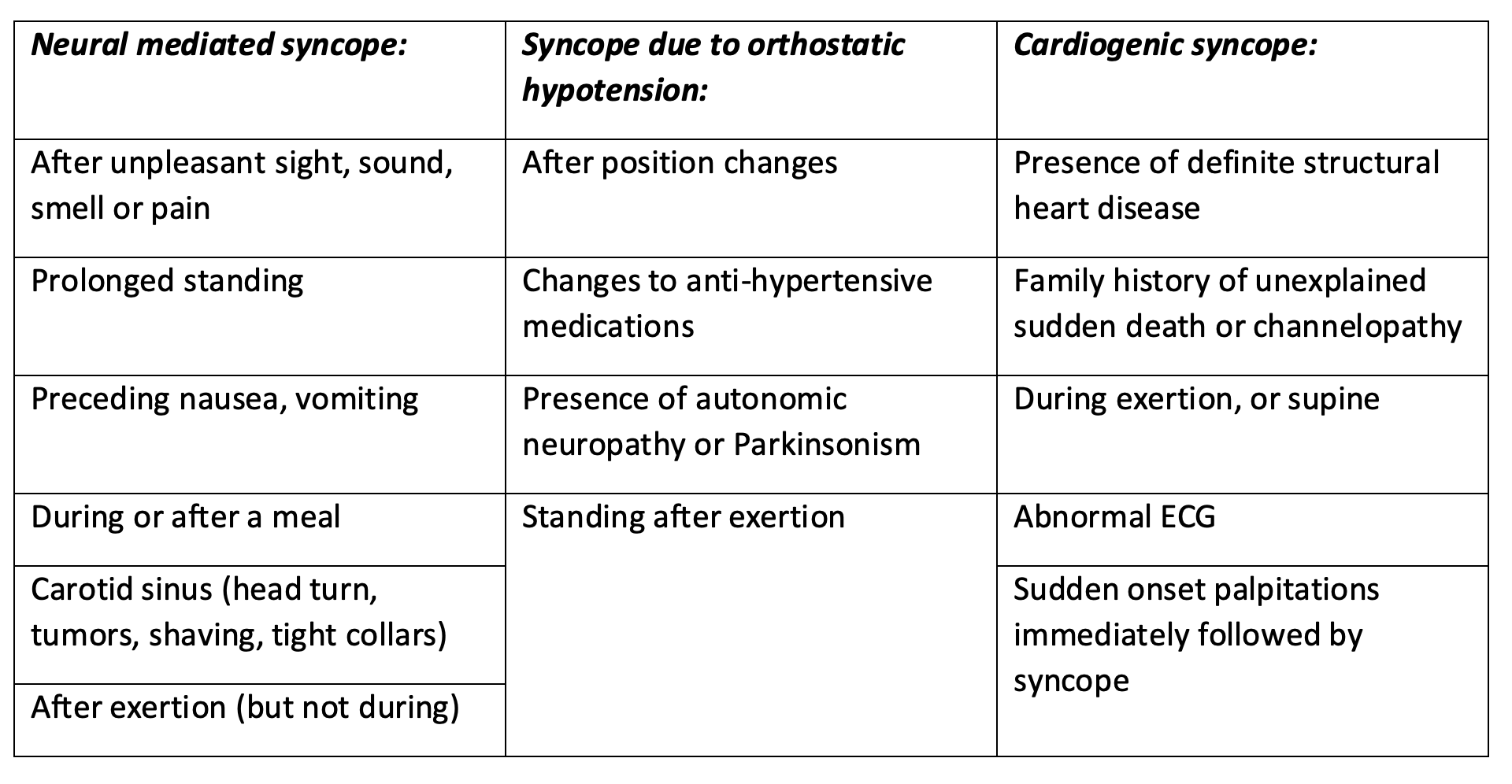

Etiologies of true syncope range from channelopathies to vasovagal syncope and can be generally categorized under neural mediated, orthostatic, or cardiogenic. Much of the time, the exact etiology cannot be determined, which underscores the importance of assessing patient risk.

In one study of patients followed for 17 years, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in cardiogenic syncope cases was 2.01 (95% CI, 1.48 to 2.73). (4) Those with an unknown cause for syncope demonstrated a hazard ratio of 1.32 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.60). (4) Meanwhile, patients determined to have had vasovagal or neural mediated syncope had no significant increased mortality. (4) For the Emergency Department provider, the approach to syncope should focus on risk stratification for each patient. A detailed history (including assessment of risk factors), physical exam, and ECG are the first steps in ED evaluation. Providers must identify red flags when they exist, and these have been well described in the literature (such as in the AHA 2017 recommendations). (1, 5) However, when clear red flags are absent, deciding on whether a patient is safe to go home or requires admission becomes more difficult. Several decision tools have been published, and most have limitations. This article will review some important historical clues and red flags in the ED evaluation of syncope, then summarize three important decision support tools to help ED providers decide whether the patient in front of them can safely go home.

History (1, 5)

Be sure to obtain history form any available witnesses.

Evaluation (1, 5)

1. EKG

2. Laboratory testing as clinically indicated (but not always necessary)

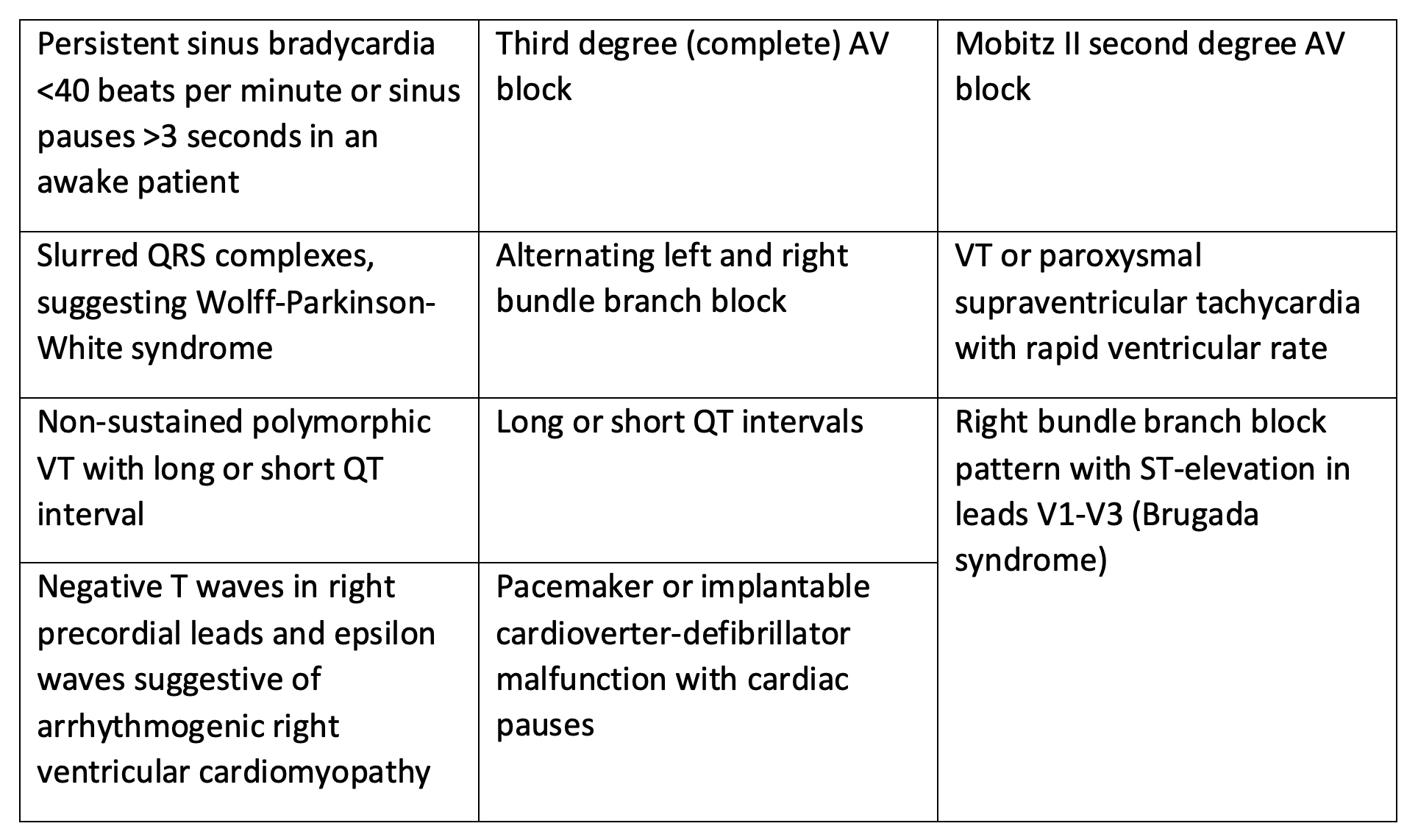

ECG and ED Monitor Red Flags (1, 5)

The following findings, should they appear in the history, workup, or in ED monitoring should prompt consideration of the patient’s syncope as high risk and in need of observation or inpatient monitoring: significant structural heart disease or CAD (including reduced LVEF, heart failure, CAD with prior MI, severe aortic or mitral stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). Providers with POCUS training may use ultrasound if there is concern based on patient presentation.

Red Flags on EKG and Monitor

Laboratory Red Flags (1, 5)

-Anemia

-Electrolyte abnormalities in the setting of EKG changes

-Elevated troponin

-Elevated BNP

-Elevated d-dimer

What about PE?

Pulmonary Embolism in Syncope Italian Trial (PESIT) found a prevalence of PE of 16.7% in patients hospitalized for first time syncope, spreading fear of widespread missed cases of pulmonary embolism. (6) The study, however, was severely limited by selection bias. Further exploration of PE in patients with syncope in a multi-center prospective cohort by Thiruganasambandamoorthy et al puts the prevalence at 0.6%. Clinical suspicion of PE, including evidence of right hear strain or tachycardia on EKG, should absolutely be considered but there is no role for reflexive venous thrombosis workup in all presentations of syncope. (7)

Decision Rules

San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR)

- CHF history

- HCT <30%

- EKG abnormal (change or non-sinus rhythm)

- SOB

- SBP <90mmHg

Prospectively validated cohort study compared application of this rule to physician judgment for serious outcomes at 7 and 30 days. Patients who meet any of the above criteria were found to be high risk for serious outcomes at 7 and 30 days with a high sensitivity (98% sensitivity, 95% CI 89-100%) but low specificity (56%, 95% CI 52-60%) for predicting serious outcomes. (8)

This decision tool uses an easy to remember mnemonic, “CHESS.” Overall, physician judgment, when compared to the San Francisco Syncope Rule was found to be more conservative with increased admission rates. Studies to externally validate these results did not show the same high sensitivity, and continued to show a low specificity. (9)

Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS)

Interpretation:

3-5 points: high risk 19.7% 30-day serious adverse events (SAE)

1-2 points: medium 5.1% risk of 30-day SAE (death, arrhythmia, MI)

0- -1 points: low 1.9%

-2- -3: very low 0.4-0.7% risk

Prospective cohort study. With a score of -1 or lower, low to very low risk, the CSRS sensitivity was 97.8% (95% CI, 93.8 – 99.6%) and specificity was 44.3% (95% CI, 42.7 – 45.9%). Breaking it down further, 0.3% at very low risk and 0.7% at low risk experienced serious 30-day outcomes. Around 20% and 50% of high risk and very-high risk patients respectively experienced serious 30-day outcomes. (10, 11)

The CSRS more comprehensively addresses risk and stratifies between different risk brackets based on a numeric score rather than a “rule out” decision score such as the SFSR. Validated in 9 major Canadian EM departments. It does require a troponin which may go beyond what is performed for initial laboratory work up of syncope. (11)

FAINT Score >60 years old

- Heart Failure +1

- History of arrhythmia +1

- Abnormal EKG +1

- Elevated BNP +2

- Elevated troponin +1

Prospective, observational study. A FAINT score of 0 versus ≥1 had a sensitivity of 96.7% (95 CI 92.9-98.8%) and specificity 22.2% (95% CI 20.7-23.8%) for excluding death and serious cardiac outcomes at 30 days. (12) The FAINT score, however, has not been externally validated.

The FAINT score is useful in particular for older patients who cannot easily be clinically determined to be low risk due to age. It does, however, require both BNP and troponin.

Importance of Clinical Judgement

Each of these decision rules show high sensitivity for poor outcomes coupled with poor specificity. Theses “rule out” tools, when negative, should appropriately reassure providers towards safely discharging patients to outpatient follow-up. This particularly applies to those patients whose disposition is not clear after the initial work up. The need for laboratory testing is a limitation in these three tools, particularly FAINT, with both troponin and BNP testing, although it addresses a group that is at higher risk due to age. SFSR requires only basic labs with the hematocrit, and may appear more attractive than routinely obtaining a troponin in patients with syncope. A more detailed laboratory work-up may be required in cases where initial history and physical examination makes disposition unclear. It is important to note the varying degrees of external validation across all three of these decision rules

Conclusion and Case Wrap Up

The patient has no clear risk factors or red flags from the history and work-up. However, with a vague story, his presentation does not completely reassure the provider that his episode was due to neural mediated (low risk) syncope. He is a good candidate for basic labs and application of a decision tool to assist the provider in determining the optimal disposition. With unremarkable basic labs and using the SFSR, he is negative for all the criteria. With no events on the monitor nor recurrence of symptoms in the ED, he is a good candidate for discharge to home with PCP follow up.

Defining the etiology of syncope based on history (including assessment of risk factors), exam, EKG, POCUS (dependent on experience/training) and laboratory testing when indicated, provides the ED physician with a framework to make safe decisions on disposition of syncope. The incorporation of risk stratification tools, such as SFSR, CSRS, and FAINT, with high sensitivity for serious adverse events, can assist ED providers in these disposition decisions, and support shared decision making with individual patients.

Pearls

-Many patients with syncope can go home after evaluation for etiology, assessment of risk factors, and obtaining a reassuring EKG.

–Clinical judgment alone often tends to err on the side of conservative dispositions and can lead to higher admission rates.

– Decision-making tools, despite their varying level of external validation, can be used to reassure clinicians and assist in shared decision-making when considering safe discharge of syncopal patients.

-The SFSR requires only basic labs (CBC, BMP) and a standard workup, and is the easiest to remember at the bedside, but sensitivity for adverse events was much lower in external validation studies. The CSRS requires more extensive laboratory testing but has proven more reliable in external validation. The FAINT score appears promising for older patients who present with syncope, but requires external validation before widespread clinical use.

References:

- Costantino G, Sun BC, Barbic F, et al. Syncope clinical management in the emergency department: a consensus from the first international workshop on syncope risk stratification in the emergency department. Eur Heart J 2016; PMID: 26242712

- Patel PR, Quinn JV. Syncope: a review of emergency department management and disposition. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015; PMID: 27752576

- Sun BC. Quality-of-life, health service use, and costs associated with syncope. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013; PMID: 23472773.

- Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Chen MH, Chen L, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002; PMID: 12239256

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society 2017; PMID: 28280231

- Prandoni P, Lensing A, Prins M, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016; PMID: 27797317

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti M, Rowe B, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Emergency Department Patients With Syncope: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. January 2019; PMID: 30691921

- Quinn JV, Stiell IG, McDermott DA, Kohn MA, Wells GA. The San Francisco Syncope Rule vs physician judgment and decision making. Am J Emerg Med. 2005; PMID: 16182988.

- Sun BC, Mangione CM, Merchant G, Weiss T, Shlamovitz GZ, Zargaraff G, Shiraga S, Hoffman JR, Mower WR. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; PMID: 17210201.

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Multicenter Emergency Department Validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. March 2020; PMID: 32202605

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016; PMID: 27378464

- Probst MA, Gibson T, Weiss RE, Yagapen AN, Malveau SE, Adler DH, Bastani A, Baugh CW, Caterino JM, Clark CL, Diercks DB, Hollander JE, Nicks BA, Nishijima DK, Shah MN, Stiffler KA, Storrow AB, Wilber ST, Sun BC. Risk Stratification of Older Adults Who Present to the Emergency Department With Syncope: The FAINT Score. Ann Emerg Med. 2020; PMCID: PMC6981063.

1 thought on “Syncope in the ED: Who can go home?”

Love your tireless selfless work. I am forever in debt to all that contribute to FOAM.

I think it’s a salient point that the SFSR was inappropriately treated in the EBM world with validation studies. It was clear that these studies showed clinician inclusion of high risk patients by predictive variables. As such, I don’t think the true performance of the instrument is known.

Man, do I worship everything Canadian, especially when it comes to EM. Such a bummer that troponin was included in this CDR. I raised this point at SAEM in small group sessions but couldn’t really understand the answer – I think we need a troponin free CDR. but the world is moving towards bloodwork for every patient every encounter.