Authors: Sushant Kapoor, DO (EM/IM Resident Physician, Christiana Care) and Eli Zeserson, MD (EM Attending Physician, Christiana Care) // Edited by: Jamie Santistevan, MD (@jamie_rae_EMdoc, EM Admin and Quality Fellow / University of Wisconsin), Brit Long, MD (@long_brit, SAUSHEC / USAF) and Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital)

INTRODUCTION

You walk into the room of a patient with the chief complaint “chest pain” and catch a glimpse of the ECG as it prints from the machine. The patient looks bad, he’s sweaty and pale, and the ECG looks equally bad. You can see tombstone ST-segments from across the room. Thankfully, in this situation, you know exactly what to do. This patient needs the cath lab, and fast! But unfortunately, emergency medicine is not always so simple. In fact, more commonly you are greeting the patient with chest pain who looks quite well and is wondering whether or not his pain is just heartburn from last nights lasagna. On his ECG you do notice some subtle ST-segment and T-wave changes. You wonder, could it be unstable angina or NSTEMI? What is the best treatment option for these patients? The next steps in the care for this patient are less clear-cut than the patient with STEMI. In this post, we will explore definitions, risk stratification instruments, and the existing evidence for various treatment options for patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI.

BACKGROUND

ACS is an term that defines a spectrum of conditions involving acute myocardial ischemia and/or infarction. Chest pain from myocardial ischemia can be subdivided into ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) or Non-ST-Elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

NSTE-ACS is the umbrella term defining the continuum between Unstable Angina (UA) and Non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI).1,2 ST-depression, transient ST-elevations and T-wave inversions may be present in UA and NSTEMI, but it is the presence of elevated cardiac biomarkers that distinguish NSTEMI from UA. Approximately 780,000 people in the United States will experience Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) and 70% of these people will have NSTE-ACS.2

The treatment of the patient with STEMI is straightforward. These patients should be rushed to the catheterization lab or given thrombolytic therapies (in hospitals not equipped with a cath lab) to restore flow to the occluded coronary artery. NSTE-ACS management is not as straightforward. The varying degrees of coronary obstruction and the overall risk profile of the patient complicates the final disposition in the emergency department, making management of NSTE-ACS patients both frustrating and exciting.

Figure 1: Classification of ACS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque is present in the coronary vessels long before the patient presents to the emergency department with physical complaints.3 The thin fibrous cap of this plaque is prone to rupture, leading to thrombus formation that can occlude the vessel or send off emboli to occlude a microvessel.3,4 This leads to edema and necrosis of myocardium and subsequent troponin leakage. If this occurs but the patients ECG does not develop ST-segment elevation, the patient is diagnosed with NSTEMI. On the other hand, subtotal occlusion or transient blood flow disruption that spares the myocardium from necrosis, (no troponin leakage), defines unstable angina.5

Figure 2: Pathophysiology of ACS5

INITIAL EVALUATION

The classic teaching is that the patient with unstable angina presents with chest pain/pressure that lasts > 10 minutes, is more severe than prior pain episodes, may occur at rest or is now occurring with much less exertion.

It is important to note, however, that not all patients with NSTE-ACS will have chest pain as their chief complaint, especially the elderly, diabetics and women. Atypical features, such as dyspnea, weakness, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, shoulder, neck, or jaw pain, should NOT exclude ACS from your differential.

Historical factors that increase the likelihood of ACS:6,7

- Older age

- Male sex

- Family history of premature CAD

- Peripheral arterial disease, diabetes, renal insufficiency

- Prior MI and prior revascularization

Symptoms associated with higher risk of MI include radiation of pain to the upper extremities (particularly radiation to both arms) and pain associated with diaphoresis or nausea and vomiting.8

Pleuritic chest pain and reproducible chest pain are uncharacteristic in the presentation of ACS,9 but, unfortunately, not entirely sensitive for excluding ACS. The Multicenter Chest Pain Study, found ACS in 22% of patients who had stabbing chest pain, 13% with pleuritic chest pain and in 7% of patients with reproducible chest pain.10 The physical examination can be completely normal in ACS and is more helpful in ruling in or out diagnoses such as CHF, aortic dissection, and pneumothorax. It is essential to consider these and other alternative diagnoses such as myocarditis, perforating peptic ulcer disease and esophageal rupture to avoid mistakenly administering anticoagulants or thrombolytics to patients in which harm may result.

DIAGNOSIS

Electrocardiogram

An initial ECG within 10 minutes of arrival to the ED should be performed in evaluation of ACS.2,11 If this initial ECG is non-diagnostic and patient has ongoing symptoms, repeat ECG should be obtained in 15-30 minute intervals during the first hour.2,11 ACS is a dynamic process and a patient with ongoing chest pain can develop ST-segment and T-wave changes over the course of minutes to hours.

The ECG is an important tool for risk stratifying patients. Multiple studies have shown that ST-depression or transient elevations increase risk of NSTE-ACS,9,12,13 and ECG features can be used to predict the risk of bad outcomes. Unfortunately normal ECGs can be seen in up to 20% of patients with NSTE-ACS.13

A prospective, 3-year study, at 18 clinical centers of 1400 patients who were admitted for NSTE-ACS found that 60% had no ECG changes, ~12% had ST-deviations >1 mm, 20% had T-wave inversions and 7% had new LBBB. One-year mortality was highest among patients with LBBB (23%) followed by ST-deviations on ECG (~10%). T wave inversions and no ECG changes both had mortality of 5% at one-year.14 These findings suggest that T-wave inversions may be useful for differentiating myocardial ischemia from noncardiac chest pain, but add little the long-term risk stratification.

Cardiac Biomarkers

Troponin should be measured on initial presentation and repeated at 3 and 6 hours from symptom onset.2 If the time of onset of symptoms is unknown, the time of presentation equals time of onset for trending troponin values. The cut-off point for myocardial necrosis is troponin above the 99th percentile of upper reference level. Serial troponins that increase or decrease by >20% can confirm diagnosis of NSTE-ACS.2

Keep in mind that different medical centers will have different assays and the value may not become abnormal for up to 12 hours. Other cardiac biomarkers, such as creatine-kinase myocardial isoenzyme (CK-MB) and myoglobin are less sensitive and specific for ACS. CK-MB requires a significant amount of tissue injury for detection. Troponin is more specific to the myocardium and also has high clinical sensitivity.2,11 For these reasons, troponin is the preferred cardiac biomarker when evaluating ACS.

Elevation of troponin does reflect necrosis of the myocardium, but does not indicate the underlying mechanism. Remember, there are many other causes of troponin elevation including: 2,15

- Tachy- or bradyarrhythmias

- Critical illness especially DKA, sepsis, respiratory failure

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Coronary vasospasm

- Stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Traumatic cardiac contusion

- Congestive heart failure

- Renal failure

- Aortic dissection

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- Significant burns

- Myocarditis or infiltrative cardiomyopathy

- Pulmonary embolism

It is important to use careful judgment when determining the most likely cause of elevated troponins and the lab value should always be applied to the clinical context instead of being used in isolation.

TREATMENT

Once the patient is diagnosed with NSTE-ACS, a combination of common therapies, including oxygen as needed, antianginal, antiplatelet and anticoagulants are initiated.

Oxygen

Unless the patient is in respiratory distress, has O2 saturation < 90% or high risk features of hypoxemia, oxygen is not indicated.2

Anti-anginals

Patients with ischemic chest pain and without contraindications to nitroglycerin should continue to get nitroglycerin for up to 3 doses. After 3 doses, IV Nitroglycerin is indicated, especially in the presence of 1) persistent chest pain, 2) hypertension and 3) heart failure.2 Relief of chest pain with nitroglycerin was seen in 35% of patients with NSTE-ACS compared with 41% without NSTE-ACS.16 Therefore, resolution of pain with nitroglycerine is neither sensitive nor specific in the diagnosis ACS.

IV Morphine Sulfate (1mg-5mg) should be considered when nitroglycerin has been maximized. No randomized controlled trials have studied the use of morphine in NSTE-ACS and no optimal dose has been defined.2

Oral Beta-blockers or calcium-channel blockers and high-intensity statins should be initiated within the first 24 hours of presentation, but generally do not need to be given immediately in the emergency department.2

Anti-platelet

If there are no contraindications, every patient presenting with NSTE-ACS should be given an initial dose of aspirin 162mg to 325mg, keeping in mind that higher doses are not more effective.2,17,18 Giving aspirin as soon as possible produces up to 46% reduction in composite events of non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke and vascular death in patients with NSTE-ACS.18 The first dose should be chewed or crushed to establish high blood levels quickly. Patients with contraindications to aspirin can be give 75mg Clopidogrel as a substitute.17,18

Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy

In addition to aspirin, clopidogrel is part of the dual-antiplatelet therapy and should be initiated regardless of definitive treatment of NSTE-ACS.17 Having both aspirin and clopidogrel on board prevents platelet adhesion and aggregation, which are the earliest steps in coronary artery thrombus formation. The loading dose of clopidogrel is 300mg. Clopidogrel should not be initiated without a conversation with the cardiologist due to the possibility of the patient undergoing early CABG, in which case clopidogrel could lead to increase bleeding risk.17,19

The CURE trial found that dual-antiplatelet therapy considerably decreased the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI or stroke, when compared to aspirin alone (9.3% vs. 11.3%, respectively).19 The cardiovascular benefit outweighed the risk of major, non-life threatening, bleeding in low, intermediate and high-risk patients, as defined by the TIMI score, with the greatest absolute benefit in higher risk patients.17,19

Figure 3: The CURE trial primary outcomes (cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI or stroke in one year)17,19

Anti-coagulation

Once antiplatelet treatment has been initiated, it is recommended that all patient should be started on anticoagulation, irrespective of treatment strategy.2 Although, multiple anti-coagulants can be used, enoxaparin has the best evidence for use in decreasing recurrent cardiac events.20,21,22

The ESSENCE trial found Enoxaparin to be more effective than unfractionated heparin in preventing death at 30 days.20 The rates of recurrent ischemic events and invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were also greatly reduced when enoxaparin was used over unfractionated heparin.21 As always, exercise caution in using enoxaparin in the setting of a reduced creatinine clearance.

Fibrinolytics

There is a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and myocardial infarctions in NSTE-ACS patients treated with fibrinolytics23 and they are therefore are not indicated.2

DISPOSITION

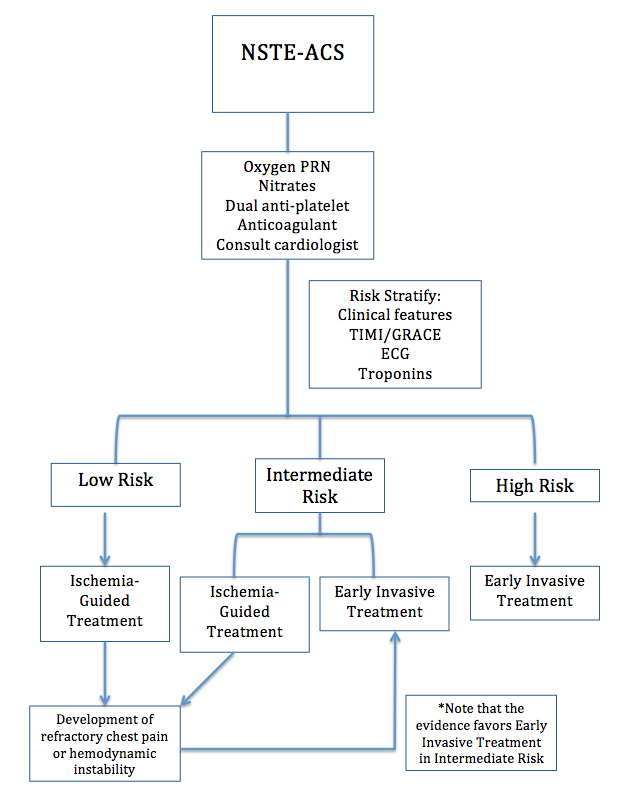

Optimal treatment for patients with NSTE-ACS is not as clear-cut as those with STEMI. After diagnosing NSTE-ACS and initiating treatment with anti-platelet, anti-anginal and anticoagulant medications, there are three pathways to definitively treat NSTE-ACS:

- Immediate invasive strategy, (angiography and revascularization) within 2 hours.

- Early-invasive treatment, (angiography followed by revascularization) within 24 hours.

- Ischemia-guided treatment involves maximal medical therapy with antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents.

Immediate-Invasive Treatment

Immediate-invasive treatment is indicated for the patient with NSTE-ACS that continues to have refractory angina despite intensive medical therapy, hemodynamic instability due to cardiogenic shock or overt heart failure, or sustained VT or VF, despite maximal medical therapy.2 Within 2 hours, these patients should be taken to the catheterization lab or transfer to a facility with interventional capabilities.

Risk Stratification

If the patient is not going immediately to the cath lab, then further risk stratification is needed. Characterizing patients into low, intermediate or high-risk groups using risk-assessment tools can help identify those patients that will benefit from early-invasive treatment.23

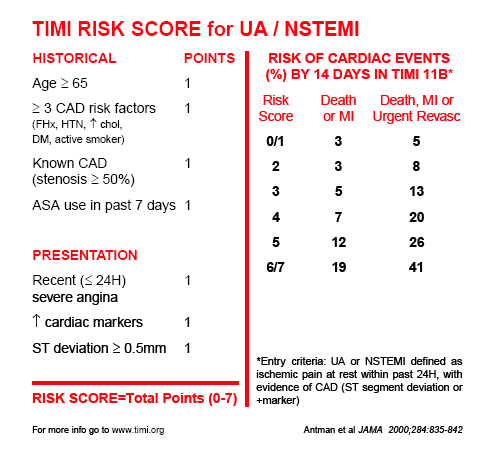

The TIMI and GRACE risk scores are two important risk stratification tools that the emergency physician can use to assess the risk of future adverse events. It is important to note that the end points of the two risk scores are different. The TIMI Score correlates with adverse events at 14 days, while the GRACE Score predicts the risk of mortality during hospitalization and at six-months.24,25

Figure 4: GRACE Risk Score calculator

Figure 5: GRACE Risk Score predicted mortality in hospital and at 6 months24

Figure 6: TIMI Risk Score and risk of cardiac events in 14 days25

Early-Invasive Treatment

When a patient with NSTE-ACS has any of the below features, they benefit more from early-invasive management:2,23

- GRACE Score >140, TIMI Score > 3

- Temporal change in Troponin or

- New or presumably new ST-depressions

Although these are the current recommendations, the decision for invasive management should be coordinated with the cardiologist.

Ischemia-guided Treatment

Formerly known as early-conservative treatment, ischemia-guided treatment involves maximum medical therapy with dual-antiplatelet therapy and anti-coagulants and is the preferred treatment for:2,23,32

- TIMI score 0-2 (low risk) or GRACE Score < 109

- Low risk, Troponin-Negative Women

- Absence of high-risk features

Multiple studies have shown equivocal outcomes between early-invasive and ischemia-guided treatment in low-risk patients.23,26,27 However, if the low-risk patient is in the emergency department and starts having recurrent chest pain or becomes hemodynamically unstable, then invasive management should be pursued.

SUMMARY:

Figure 7: Algorhithm for risk stratification and treatment of patients with UA/NSTEMI

THE EVIDENCE FOR EARLY-INVASIVE MANAGEMENT

Lakhani et al. Correlation of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score with extent of coronary artery disease in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010.

- In this cross-sectional study, patients with TIMI Score from 5 to 7 were more likely to have severe coronary stenosis and multi-vessel disease compared to those with TIMI scores between 0 and 2. The higher the TIMI score, the more likely the left main artery was diseased. 28 Therefore, patients with a TIMI Score > 3 (intermediate risk) and TIMI Score > 5 (high risk) are likely to benefit from early-invasive management.

Cannon et al. Comparison of Early Invasive and Conservative Strategies in Patients with Unstable Coronary Syndromes Treated with the Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor Tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001.

- TACTICS-TIMI 18 trial found the rate at which composite outcome of death, non-fatal MI or pre-hospitalization for ACS in 6-months was lower in early-invasive treatment vs. conservative treatment (16% vs. 19.4%, respectively) for patients with NSTE-ACS who were also treated with Tirofiban (GIIb/IIIa inhibitor).29 The rate of recurrent ischemic chest pain was also reduced.

Fox et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002.

- Patients with NSTE-ACS undgeroing early-invasive treatment were less likely to suffer from the composite endpoint of death, MI or rehospitalization with ACS at 4 and 12 months.30 It should be noted, however, that the benefits of early-invasive therapy at 5-years were primarily seen in the highest risk patients.31

O’Donoghue et al. Early Invasive vs Conservative Treatment Strategies in Women and Men With Unstable Angina and Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2008.

- A meta-analysis of 8 randomized-controlled trials looking at early-invasive vs. conservative management found statistically-significant reduction in composite outcome of death, MI or ACS, favoring the invasive strategy in men and high-risk women, with the latter being defined as troponin-positive.32

REVISITING ECG AND TROPONIN

The utility of an initial ECG and troponin level in NSTE-ACS patient is not only for diagnosis, but also for prognosis and defining ultimate management. ECG changes, specifically ST-deviations, and troponin elevations have been analyzed in NSTE-ACS for 1,846 patients in the TACTICS-TIMI 18 trial. In this study, ST-deviations were categorized into 1) T-wave inversions 2) ST-depression 0.05-0.09mV 3) ST-depression >0.10mV and 4) transient ST-elevations >0.10mv. Troponin levels were also categorized into 1) High level (>0.1ng/ml) 2) Low level (.01-0.1ng/ml) and 3) Negative (<0.01ng/ml).33

The rate of death or MI by 6 months with each category of ST-deviations and troponin level in NSTE-ACS patients was studied, first independently of each other and then combined. The findings showed:33

- Higher rate of death or MI by 6 months was seen with higher magnitude of ST-deviations (Table 1).

- Patients with ST-deviations were more likely than those without to have initial troponin elevated.

- Worse prognosis was seen with higher initial troponin level AND more severe ST-deviation.

- Patients with higher troponin levels and more ST-deviations had more extensive coronary artery disease.

- The patients with higher troponin levels and more severe ST-deviations had a higher rate of failure of medical therapy.

| Initial ECG Abnormality | Rate of Death or MI by 6 months |

| None | 7.1% |

| T-wave Inversions | 5.5% |

| ST-Depression 0.05-0.09mV | 9.3% |

| ST-Depression >0.10mV | 14.2% |

| Transient ST-Elevation >0.10mV | 12.3% |

Table 1: Rate of Death or MI by 6 months in relation to initial ECG abnormality.33

Based on this evidence, the degree of ST-deviation and extent of troponin elevation can serve as independent prognostic factors in NSTE-ACS patients. Therefore, a comprehensive risk stratification includes TIMI and GRACE score as well as initial ECG and troponin findings to best identify those patients who will receive the greatest advantage from early-invasive treatment.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

- A completely normal ECG does not exclude ACS and occurs in 1-6% of patients.

- Repeat ECGs can be helpful in making the diagnosis of NSTE-ACS and should be used liberally.

- Troponin levels should be repeated at least 3-6 hours after symptom onset.

- Relief of chest pain with nitroglycerin cannot rule in or out NSTE-ACS.

- After diagnosis of NSTE-ACS risk-stratification is helpful to guide further management.

- Consider ECG changes and troponin levels along with initial presentation when risk-stratifying patients.

- Atypical symptoms such as weakness and nausea should not exclude NSTE-ACS from differential diagnosis, especially in the elderly, diabetics and women.

- Available data suggests that patients with troponin elevations at time of diagnosis of NSTE-ACS will benefit from early-invasive treatment.

References/Further Reading:

- Breall JA, Simons M, Alpert JS, et al. Risk stratification after non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. In C.P. Cannon, J.C. Kaski, A.S. Jaffe, B.J. Gersh, P.A. Pellikka (Ed.), (2016). Retrieved from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/risk-stratification-after-non-st-elevation-acute-coronary-syndrome

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Dec 23;130(25), 2354-2394. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25249586

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis from pathophysiology to practice. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2009 Dec 1:54(23):2129-38. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19942084

- Jaffe R, Charron T, Puley G, et al. Microvascular obstruction and the no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2008 Jun 17;117(24):3152-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18559715

- Chang H, Min JK, Rao SV, et al. Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Targeted Imaging to Refine Upstream Risk Stratification. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2012 Jul;5(4), 536-546. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22811417

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=12485966

- Miller CD, Lindsell CJ, Khandelwal S, et al. Is the initial diagnostic impression of “noncardiac chest pain” adequate to exclude cardiac disease? Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Dec;44(6):565. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=15573030

- Swap CJ and Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005;294(20):2623. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=16304077

- Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA. 1998 Oct 14;280(14):1256. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=9786377

- Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg M, et al. Acute chest pain in the emergency room. Identification and examination of low-risk patients. Arch Intern Med. 1985 Jan;145(1):65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3970650

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2012 Oct 16;126(16), 2020-2035. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22923432

- Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernick PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10938172

- Pope JH, Ruthazer R, Beshansky JR, et al. Clinical Features of Emergency Department Patients Presenting with Symptoms Suggestive of Acute Cardiac Ischemia: A Multicenter Study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998;6(1):63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=10751787

- Cannon CP, McCabe CH, Stone PH, et al. The electrocardiogram predicts one-year outcome of patients with unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI III Registry ECG Ancillary Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997; 30: 133–140. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9207634

- Thygesen K, Mair J, Katus H, et al. Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. Recommendations for the use of cardiac troponin measurement in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(18):2197. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=20685679

- Grailey K and Glasziou PP. Diagnostic accuracy of nitroglycerine as a ‘test of treatment’ for cardiac chest pain: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(3):173. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=21511974

- Simons, M., Cutlip, D., Lincoff, M.A. Antiplatelet agents in acute non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. In C.P. Cannon, F. Verheugt (Ed.), (2010). Retrieved from https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/contents/antiplatelet-agents-in-acute-non-st-elevation-acute-coronary-syndromes?source=search_result&search=Antiplatelet+agents+in+acute+non-ST+elevation+acute+coronary+syndromes&selectedTitle=1%7E150#H4

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11786451

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11519503

- Cohen M, Demers C, Gurfinkel EP, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-Wave Coronary Events Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(7):447. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=9250846

- Goodman, S. G., Cohen, M., Bigonzi, F., et al. Randomized trial of low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin) versus unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;36(3), 693-698. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=10987586

- Antman EM, McCabe CH, Gurfinkel EP, et al. Enoxaparin prevents death and cardiac ischemic events in unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 11B trial. Circulation. 1999;100(15):1593. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=10517729

- Cannon, CP and Turpie AG. Unstable Angina and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Initial Antithrombotic Therapy and Early Invasive Strategy. Circulation. 2003;107(21), 2640-2645. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12782615

- Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous, et al. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Investigators. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14581255

- Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernick PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision-making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16;284(7):835-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10938172

- Damman P, Hirsch A, Windhausen F, et al. 5-Year Clinical Outcomes in the ICTUS (Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable coronary syndromes) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(9), 858-864. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20045278

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus Delayed Invasive Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21), 2165-2175. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19458363

- Lakhani MS, Qadir F, Hanif B, et al. Correlation of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score with extent of coronary artery disease in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010 Mar;60(3):197-200. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20225777

- Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al. Comparison of Early Invasive and Conservative Strategies in Patients with Unstable Coronary Syndromes Treated with the Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor Tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(25),1879-87. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11419424

- Fox K, Poole-Wilson P, Henderson R, et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9335), 743-751. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12241831

- Fox K, Poole-Wilson P and Clayton T. 5-Year Outcome of an Interventional Strategy in Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome: The British Heart Foundation RITA-3 Randomized Trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):914-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16154018

- O’Donoghue M, Boden WE, Braunwald E, et al. Early Invasive vs Conservative Treatment Strategies in Women and Men With Unstable Angina and Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2008;300(1), 71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18594042

- Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Mccabe CH, et al. Combination of quantitative ST deviation and troponin elevation provides independent prognostic and therapeutic information in unstable angina and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006;151(1), 25-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16368287

2 thoughts on “Current ED Management of Non-ST Segment Elevation MI (NSTEMI): A Practice Update”

Pingback: Global Intensive Care | Current ED Management of Non-ST Segment Elevation MI (NSTEMI): A Practice Update

Pingback: For Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome Do I Need to Start a Heparin Drip? - Bold City Emergency Medicine