Author: Rachel Bridwell, MD (@rebridwell, Emergency Medicine Resident, San Antonio, TX) // Edited by: Jamie Santistevan, MD (@jamie_rae_EMdoc – EM Physician, Presbyterian Hospital, Albuquerque, NM); Manpreet Singh, MD (@MPrizzleER – Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine / Department of Emergency Medicine – Harbor-UCLA Medical Center); and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit – EM Attending Physician, San Antonio, TX)

Welcome to this edition of ECG Pointers, an emDOCs series designed to give you high yield tips about ECGs to keep your interpretation skills sharp. For a deeper dive on ECGs, we will include links to other great ECG FOAMed!

The Case:

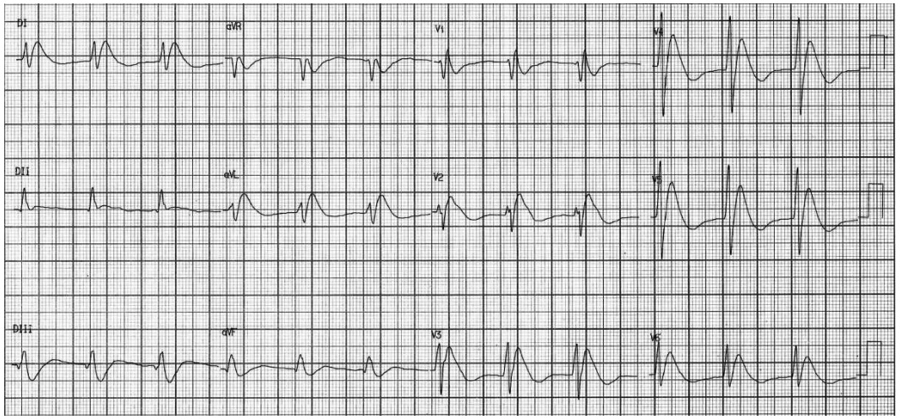

You are on a evening shift and an ECG gets handed to you, which looks concerning on first glance. The patient is an 87-year-old male brought in by his wife who has a chief complaint of altered mental status, increased sleep, and decreased appetite. You smartly grab an old ECG, which was normal. What do you want to do? Call a code STEMI? Call cardiology? Resuscitate?

V1-2 look very concerning– there appears to be ST-segment elevation, but no reciprocal changes. The QRS is wide, and there are V1-V2 J-point elevations and T-wave inversions that resemble a saddle or ski-slope. Upon further questioning, the patient has a remote history of MI and recent stent placement earlier this year with a total of 5 stents. On initial examination, the patient is febrile to 101.4F rectally, current BP 100/60, A&Ox2, and is non-ambulatory at baseline. What is going on with this ECG?

Pseudobrugada Pattern:

For a brief review, Brugada syndrome is the most common hereditary channelopathy, with an ECG showing characteristic wide QRS, J-point elevations, and T-wave inversion in V1-V2 (1). See this ECG Pointers for more. It is associated with ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in structurally normal hearts. Diagnosis of Brugada syndrome requires the characteristic ECG pattern to be present in addition to clinical criteria such as ventricular fibrillation or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, syncope, family history of sudden cardiac death, inducible VT with electrical simulation or nocturnal agonal respirations.

However, the Brugada pattern ECG morphology can also be seen secondary to a variety of acute pathology which includes but not limited to sepsis, Na+ blocking drugs (TCA and antiarrythmics, specifically class Ia, Ic), Li+, cocaine, electrolyte imbalances which is most commonly hyperkalemia, and hypothermia (2). In hyperkalemic patients these specific ECG changes portend a poor prognosis and may become apparent at serum levels of 5.8-9.4 mEq/L (3-5). Other authors note that LAD occlusion can cause Brugada pattern in certain patients with anteroseptal injury pattern (6), although lack of reciprocal changes should help guide the diagnosis away from STEMI (7).

What to do?

In the right clinical setting, Brugada syndrome may be diagnosed. When the clinical situation differs and Brugada pattern is present on ECG, one should search diligently for the underlying condition and treat it! The ECG findings will resolve, though temporal resolution varies based on the etiology. If based on history and clinical findings, the cause is likely to be acute coronary artery occlusion, then consulting cardiology for PCI would be the treatment of choice. In such situations, case reports have shown that the pseudobrugada pattern normalizes on ECG after stenting of the LAD occlusion (6-9).

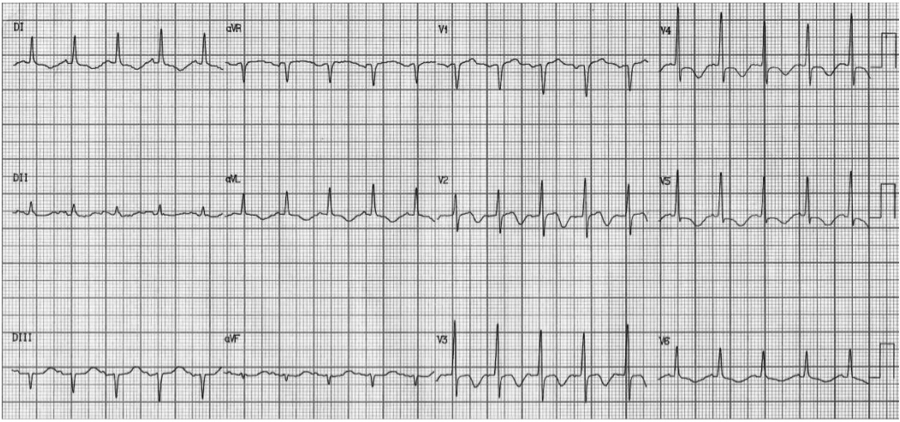

Here is another example of pseudobrugada pattern in a patient who was in VF arrest, and converted to this rhythm after defibrillation, illustrating this common post ROSC finding.

What appears at first glance to be Brugada pattern when looking at V2 actually extends to other leads throughout this ECG to include the remainder of the anterior leads and the lateral leads! This is not the case in Brugada syndrome, where the pattern is localized to V1-2, sometimes to include V3. This patients ECG represents large anterior-lateral STEMI. This patient was taken for catheterization and found to have an LAD occlusion, with his post PCI ECG seen below. Note resolution of the pseudobrugada pattern.

Case Conclusion:

Our patient’s bedside echo showed septal hypokinesis and global decreased contractility. Cardiology was consulted, who ruled no STEMI, though the troponin returned at that time which was elevated. Cardiology repeated the bedside echocardiogram and agreed with the septal hypokinesis. Heparin bolus with infusion and clopidogrel were given in anticipation for catheterization the following day. Based on suspicion of malodorous urine of a patient who has a known colovesicular fistula, sepsis secondary to a urinary source was also confirmed with UA, and fluid resuscitation was started and ceftriaxone given. Because of the known NSTEMI and decreased contractility fluid resuscitation was done in 500cc increments, starting with a POCUS that showed a very collapsible inferior vena cava. Every 500 cc, the POCUS was repeated in order to monitor for inferior vena cava dilation without respiratory variation given the high potential for pump failure in this patient. The patient was admitted to the ICU. Cardiology performed a heart catheterization 24 hours later, and noted complete occlusion of the LAD approximately 1cm distal to the LCX take off, which they successfully opened.

Take home points:

- Diagnosis of Brugada syndrome requires typical ECG morphology in addition to clinical criteria.

- Pseudobrugada morphology can occur due to a variety of acute medical pathologies including sepsis, cardiac ischemia/infarct and hyperkalemia.

- Pseudobrugada pattern alone is not a STEMI equivalent, though in the right clinical setting, cardiology intervention may be required.

- Always consider the ECG morphology in the context of the clinical setting, treat the underlying etiology, and obtain serial ECGs to watch for resolution.

References:

- Ersan T, Emir D, Mustafa A. Pseudobrugada pattern due to Hyperkalemia. 2012. J Clin Experiment Cardiol S10:001.

- Littmann L, Monroe MH, Taylor L, Brearley WD Jr. The hyperkalemic Brugada sign. 2007. J Electrocardiol 40:53-59.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, et al. Brugada syndrome. Report the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Assocation. 2005. Circ. 111:659-670.

- Junttila MJ, Gonzalez M, Lizotte E, Benito B, Vernooy K, et al. Induced Brugada-type electrocardiograp, a sign for the imminent malignant arrhythmias. 2008. Circ. 117:1890-1893.

- Tanawuttiwat T, Harindhanavudhi T, Bhan A, Dia M. Hyperkalemia-induced Brugada pattern: an unusual manigestation. 2010. J Cardiovasc Med. 11:285-287.

- Perez Riera AR. Diffuse Transient Pseudo-Brugada ECG pattern in the setting of a Left Anterior Descending Artery Obstruction. Cardiolatina 2017. DoI: 28SEP2018.

- Jastrzebski M, Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Czarnecka D. Right ventricular tombstoning as a Brugada phenocopy. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:213-4

- Nair SR, Vellani H, Shajudeen K, Rajesh G, Sajeev CG. Pseudobrugada sign. Kerala Heart Journal. 2016: 6(1).

- Kimie O, Ichiro W, Yasuo O, et al. Brugada syndrome in the presence of coronary artery disease. Journal of Arrhythmia 2013; 29:211-216.