Originally published at EM Cases – Visit to listen to accompanying podcast. Reposted with permission.

Follow Dr. Anton Helman on twitter @EMCases

This is EM Cases main episode podcast 109 Skin & Soft Tissue Infections – Cellulits, Skin Abscess & Necrotizing Fasciitis Myths and Misperceptions

Why do EM physicians spend so little time talking about the things we see the most often? You may not be as energized for cellulitis as you are for an ED thoracotomy, but skin and soft tissue infections are encountered on nearly every shift – and you can do a lot more good for a lot more patients by recognizing and treating these common infections the right way. With a cellulitis misdiagnosis rate of up to 34%, there is definitely room for improvement. In this episode we ask Dr. Andrew Morris, ID specialist and Dr. Melanie Baimel EM specialist: How do you distinguish cellulitis from the myriad of cellulitis mimics? At what point do we consider treatment failure for cellulitis? What is the best antibiotic choice for patients who are allergic to cephalosporins? Which patients with cellulitis or skin abscess require IV antibiotics? Coverage for MRSA? What is the best and most resource wise method for analgesia before I&D of a skin abscess? What is the best method for drainage of a skin abscess? Which patients with skin abscess require a swab? Irrigation? Packing? Antibiotics? With the goal of sharpening your diagnostic skills when it comes to skin and soft tissue infections – there are lots of cellulitis mimics – and choosing wisely when it comes to treatment, we’ll be discussing best practices for management of cellulitis and skin abscesses, when to cover for MRSA, how to pick up nec fasc before it’s too late and a lot more…

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman

EBM Bottom Line by Justin Morgenstern

Written Summary and blog post by Alexander Hart & Shaun Mehta, edited by Anton Helman April, 2018

Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis that is often misdiagnosed

Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis. There are no lab values or imaging studies that will confirm the diagnosis. The classic clinical findings of cellulitis that we learn in medical school – rubor, dolor, calor tumor – are non specific markers of inflammation which you’ll see in a variety of cellulitis mimics described below. Look for fever, streaking lymphangitis and regional lymphadenopathy which all make the diagnosis much more likely, but unfortunately are only found in a minority of patients with cellulitis.

Beware of diagnostic momentum. We often see patients who have already been diagnosed with cellulitis and make the cognitive error of premature closure on alternative diagnoses.

When to consider alternative diagnoses:

- Very itchy rash

- Bilateral rash

- Not improving with antibiotics

- In a risky location (inner thigh, over a joint, genitals)

- Extreme pain or totally painless (think necrotizing fasciitis)

- If its lasting for months on end

How do you distinguish the mimics from cellulitis?

Stasis dermatitis is prob the most commonly misdiagnosed, but it is usually bilateral as well as chronic, and the redness often diminshes on passive leg raise.

Peripheral arterial disease can mimic cellulitis, but again, just do a passive leg raise and if the redness dimishes, it unlikely to be cellulitis.

DVT and cellulitis rarely co-exist – observational studies suggest that only 1% of patients with cellulitis have a concurrent DVT.

Monoarthritis such as septic arthritis/gout may have an accompanying overlying cellulitis. Examine the joint! Significant pain on passive ROM suggests monoarthritis.

Flexor tenosynovitis of the finger results in exquisite pain on passive extension of the finger which is probably the most important feature to help distinguish it from simple cellulitis.

Bee and wasps stings don’t cause cellulitis in the first few hours after the sting. Cellulitis takes time to develop so pay close attention to the timing of the redness spreading and remember that although possible, cellulitis is exceedingly uncommon after a bee or wasp sting.

Erythema Migrans of Lyme disease can look like a cellulitis but it’s usually relatively painless and nontender. It’s seasonal, and erythema migrans is usually about a 5 cm circular patch without streaking and may have some central clearing (but not necessarily).

Clinical Pearl: A test that can help you distinguish lower extremity cellulitis from the most common mimics is a passive leg raise. Lie the patient supine and elevate the leg to 45° for 1-2 minutes. Cellulitis erythema persists, whereas erythema secondary to stasis, lymphedema or peripheral vascular disease dissipates.

We are poor at distinguishing simple cellulitis from skin abscess clinically

Physical examination alone has been shown in multiple studies to have poor inter-rater agreement and poor accuracy for distinguishing simple cellulitis from skin abscess. The addition of POCUS significantly increases the diagnostic accuracy and a study by Tayal et al. showed that the addition of POCUS changed management in half of all cases, both in eliminating the need for drainage and in identifying those in need of advanced diagnostics and/or consultation.

Antibiotic treatment for cellulitis

Cephalexin, which covers both Staph Aureus and Streptococcus, is the most commonly used antibiotic for simple cellulitis but it has poor coverage for MRSA.

TMP-SMX for MRSA? A study by Moran et al., suggests that routine addition of TMP-SMX to cephalexin in patients with uncomplicated cellulitis did not result in an increased clinical cure rate.

Penicillin allergy? First, ensure a true allergy as opposed to intolerance or a side effect. Consider cephalexin if non-anaphylactic (cross-reactivity <10%). If there is concern for true anaphylaxis:

- Doxycycline (covers Lyme too!) is considered the antibiotic of choice by our experts for patients with simple cellulitis who have a true

severe allergy to penicillins or cephalosporins

severe allergy to penicillins or cephalosporins - Clindamycin*

- Macrolides*

- Fluoroquinolones

- TMP/SMX monotherapy is NOT recommended as it has poor Streptococcus coverage

*Be aware of high MRSA resistance rates with clindamycin and macrolides in some geographical areas.

IV vs. oral? The bioavailability of oral cephalexin is similar to that of IV cephazolin. No difference in clinical resolution of cellulitis has been demonstrated in multiple small studies between IV and oral antibiotics for simple cellulitis. The IDSA recommends that IV antibiotics be reserved for non-purulent cellulitis if the patient is immunocompromised (does not include diabetic patients), has systemic signs of infection (SIRS), hemodynamic instability or altered mental status. Some experts recommend IV antibiotics for simple cellulitis in patients with high BMIs because adequate serum drug levels are difficult to achieve with oral cephalexin in these patients.

Update 2018: In a retrospective chart review of 500 patients, independent predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure (defined as hospitalization, change in class of oral antibiotic or switch to IV therapy after 48 hrs of oral therapy) for non-purulent and soft tissue infections included: 1) tachypnea at triage; 2) chronic ulcers; 3) history of MRSA colonization or infection; 4) cellulitis in the past year; 5) chronic kidney disease; 6) diabetes mellitus. Abstract

Duration of treatment? The IDSA recommends 5 days of treatment for simple cellulitis, with the option to extend treatment duration in the absence of clinical improvement within this time period. Studies using fluoroquinolones have shown that 5 days is non-inferior to 10 days.

Cellulitis – The Return Visit

We have all seen the patient who presents to the emergency department with “worsening cellulitis” despite being on antibiotics.

The rash may continue to spread for the first 48 h after administration of antibiotics. This is not necessarily a failure of treatment. Many patients develop a post-phlebitic syndrome with persistent redness. An increase or decrease in the intensity of the erythema is considered by our experts to be an important variable in determining progression of cellulitis.

Consider treatment failure or an alternative diagnosis after 48-72 hours if there is:

- No improvement in pain, or

- No improvement in heat, or

- Progression of redness

Peterson et al. found that fever (OR=4.3), chronic leg ulcers (OR=2.5), chronic edema or lymphedema (OR=2.5), prior cellulitis in the same area (OR=2.1), and cellulitis at the wound site (OR=1.9) were all predictors failure of outpatient management of cellulitis.

Cellulitis – Special Populations

Obese patients. Patients with a high BMI have higher treatment failure rates in cellulitis. Although controversial, many experts suggest that IV antibiotics are more appropriate for these patients because adequate drug levels are generally not achievable with oral cephalexin, despite studies of all-comers with simple cellulitis showing no benefit of IV over oral antibiotics.

Post-partum mastitis. In addition to prescribing cephalexin educate the patient around continuing to breastfeed and highlight that there are no additional risks to baby. Avoid TMP/SMX and fluoroquinolones.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Skin Abscesses

Although most abscesses at first glance are relatively easy to diagnose and treat, there is much practice variation when it comes to effective drainage, pain control and antibiotic prescriptions.

Pain control for I&D of skin abscesses

I&D of skin abscesses has been rated as the second most painful procedure by patients next to only NG tube insertion. But short of offering all of these patients procedural sedation, there are ways to optimize more efficient and less resource intensive analgesic strategies.

Field Blocks: Rather than infiltrating the abscess directly with your local anesthetic try a field block. This will prevent attenuation of your drug’s potency in an otherwise acidic medium and avoid a mess if you inadvertently blow the top off the collection. Techniques are described on this AAFP webpage and demonstrated in this video.

Use large volumes: Be generous with your local anesthetic. Our experts recommend the use of a 25G needle bent at the hub and deliver 10mL of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine in a circumferential pattern.![]()

Nerve Blocks: These allow for more targeted use of your anesthetic and avoids local infiltration causing increased pain and difficulty with wound closure. It’s a great strategy for foreign body removal in sensitive areas like the sole of the foot. This app is available for you to reference on shift if it has been a while since your last nerve block.

Pitfall: Underdosing local anesthetic for field block for skin abscess drainage. Use 10mL of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine.

What is the best method for drainage of skin abscesses?

Incision Type: For most small, uncomplicated abscesses, a simple linear incision with an 11-blade scalpel is effective. Make sure the incision is long enough to allow for an instrument to break up adhesions and loculations, a critical step to minimize the chance of recurrence. Cruciate incisions have not been found to reduce rates of recurrence and tend to leave more noticeable scars.

Needle Aspiration: This strategy is less effective with a higher failure rate that I&D. Exceptions include ultrasound-guided breast and peri-tonsilar abscess drainage.

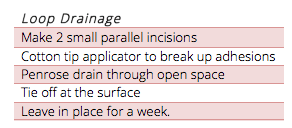

Loop Drainage: Several studies, though small, support the loop drainage technique as an alternative to the simple I&D for wounds that are more complex. The technique is well described at Academic Life in Emergency Medicine.

Which patients with skin abscesses require a swab for C&S?

The IDSA has recommends that all but the mildest abscesses be swabbed given the relatively endemic risk of MRSA. However, other EM bodies have opposed this practice. Our experts recommend that abscess swabs only be sent in the following settings:

![]()

- Multiple antibiotic allergies or intolerances

- Substantial antecedent microbiological exposure

- Treatment failure

Is irrigation of abscesses beneficial?

While our surgical colleagues use irrigation frequently in the management of abscesses in the OR, an ED study by Chinook et al in 2016 did not show benefit for this strategy in all comers. Our experts do not recommend routinely irrigating abscess. Rather they recommend wound irrigation for:![]()

- Infected traumatic wounds

- Diabetic foot ulcers with good tissue perfusion

Which skin abscesses require packing?

Packing has been shown to increase pain scores without improving clinical resolution of skin abscesses <5cm in diameter.

Loose packing (just enough to keep the wound open without falling out) is recommended for large abscesses (>5cm in diameter), abscesses in areas where skin tends to close more quickly such as around the genitals and axilla and in diabetic or traumatic wounds.

Which patients with skin abscesses require antibiotics?

This remains a controversial topic. Our experts recommend a patient centered approach to antibiotic prescribing for patients with skin abscesses as outlined in the recent BMJ guidelines.

Traditionally, it was useful to assess patients for MRSA risk factors to help in antibiotic decision making, but MRSA has become more endemic in recent years. This has led to some recent studies, such as this 2016 NEJM publication, to support the wholesale use of antibiotics in all patients with abscess citing a 7% absolute difference in outcomes and a NNT of 14. A caveat here is that there is a high associated risk of GI and allergic side-effects along with the rare but serious threat of syndromes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and C. difficile.![]() Our experts recommend Doxycyline for skin abcesses to avoid these serious side effects seen with Clindamycin and sulpha-based antibiotics. Antibiotics should beconsidered for patients with large abscesses, significant surrounding cellulitis, fever and immunocompromised state. Remember that 80% will have clinical cure with drainage alone and those who don’t are very unlikely to return floridly sick or unstable.

Our experts recommend Doxycyline for skin abcesses to avoid these serious side effects seen with Clindamycin and sulpha-based antibiotics. Antibiotics should beconsidered for patients with large abscesses, significant surrounding cellulitis, fever and immunocompromised state. Remember that 80% will have clinical cure with drainage alone and those who don’t are very unlikely to return floridly sick or unstable.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing Fasciitis is an uncommon and challenging diagnosis in its early stages. It involves the rapid destruction of fascia with systemic involvement mediated by septic and toxic processes. Mortality is 30-40% with treatment.

- “Type 1” represents a polymicrobial infection and is often gas forming (think Fournier’s gangrene)

- “Type 2” represents a mon-microbial infection, usually by G.A.S. causing a robust immune stimulation

Risk Factors for necrotizing fasciitis include immunocompromised state, blunt trauma, recent varicella infection, recent use of NSAIDs.

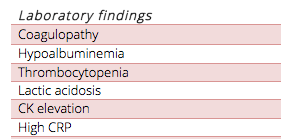

There is no set of clinical findings, lab test results and even imaging that can definitively rule out necrotizing fasciitis. If you have anything more than the slightest suspicion based on your clinical exam, consider early consultation with a surgeon and start empiric antibiotics. While lab findings and imaging findings can be supportive of the diagnosis, negative lab and imaging studies cannot rule out necrotizing fasciitis and should never override clinical judgment. When lab tests and imaging are noncontributory, the diagnosis can only be made with surgical exploration. Necrotizing fasciitis may appear like cellulitis, but alternatively may have little if any redness. Skin findings may be scant as these skin findings represent “the tip of the iceberg” of the tissue destruction in the deep tissues. Streaking lymphangitis favours the diagnosis of cellulitis over necrotizing fasciitis.

Clues to early detection of necrotizing fasciitis

- Severe pain out of proportion to physical exam findings (however a minority of patients will report little pain and may have a laisser-faire

attitude toward their illness) - Ecchymoses or skin necrosis

- Tense edema (skin may feed hard or “wooden”)

- Bullae/blisters, conjunctival injection and levido reticularis

- Palpable crepitus (often absent if bacteria is not gas producing)

- Localized skin hypoesthesia (due to local nerve destruction)

- Rapidly spreading rash over hours

- SIRS (may develop rapidly – monitor your patient carefully)

CT and MRI as well as POCUS can all help detect soft tissue gas in those with gas forming organisms driving their infection. Never delay definitive therapy in clinically obvious cases in order to obtain radiological tests.

Necrotizing Fasciitis Pitfalls in Diagnosis

- Assuming no necrotizing fasciitis in the patient who looks well. Remember that early detection of nec fasc is the key to a favorable outcome.

- Ruling out necrotizing fasciitis based on little pain, no fever and no crepitus.

- Delay to surgical debridement – doing an extensive workup in clinically obvious cases with CT/MRI etc leading to a delay to definitive surgical treatment.

Necrotizing Fasciitis Pearls in Diagnosis

- Even though diabetes and being postoperative are often cited as risk factors, necrotizing fasciitis can occur in otherwise healthy patients after a minor traumatic injury.

- Scrutinize the vitals – most patients will have tachycardia and/or tachypnea out of proportion to fever.

- If you see what appears to be a cellulitis on the lower abdomen examine the perineum for signs of Fournier’s Gangrene.

- Use POCUS to look for gas in patients with low or moderate probability – if you see gas your suspicion for nec fasc should be significantly raised.

The finger test for diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis

In the event that you don’t have slam dunk diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis clinically (low pretest probability but still a suspicion) and you can’t get rapid access to surgical exploration in the OR or confirmatory imaging for whatever reason, or that the imaging is negative but you still have a suspicion for the diagnosis, consider diagnostic confirmation with the finger test. After local anesthesia, make a 2-3 cm incision in the skin large enough to insert your index finger down to the deep fascia. Lack of bleeding and/or “dishwater pus” (grey-colored fluid) in the wound are very suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. Gently probe the tissues with your finger down to the deep fascia. If the deep tissues dissect easily with minimal resistance, the finger test is positive and necrotizing fasciitis can be ruled in.

Empiric antibiotic therapy for suspected necrotizing fasciitis

Meropenem1 g IV q8h OR Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV q6h

PLUS Vancomycin 15 mg/kg q12 h IV OR Linezolid 600 mg IV q12h

References for Skin & Soft Tissue Infections

Drs. Helman, Morris and Baimel have no conflicts of interest to declare

Other FOAMed Resources for Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Initial antibiotic of choice in uncomplicated cellulitis on Rebel EM