Authors: Catrina Cropano, MD (EM Resident Physician, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-West) and Felipe Serrano, MD (EM Attending Physician, Assistant Program Director, Mount Sinai St. Luke-West) //Reviewed by: Erica Simon, DO, MPH, MHA (@E_M_Simon); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 43-year-old male, with a previous medical history of Type II diabetes, presents to the Emergency Department (ED) for three weeks of right thigh pain, swelling, and redness. Review of systems is significant for myalgias, low-grade fevers, and a recent urgent care visit with a presumed diagnosis of cellulitis. The patient is visiting the U.S. from his home in the Dominican Republic. Triage VS: T 101F, P 127, BP 140/80, RR 18, and SpO2 100% on RA. Physical exam reveals a tender, erythematous, indurated mass localized to the right mid-thigh.

What is your differential diagnosis?

Introduction1-5

- Pyomyositis (PM) is a subacute infection of skeletal muscle most commonly caused by aureus. Additional etiologies include: Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, E. coli, and H. influenzae.

- PM is typically hematogenous in origin and is associated with immunocompromisedstates, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, intravenous drug use, rheumatologic disorders, and trauma.

- PM was historically considered a disease of the tropics (Africa and South Pacific), occurring most frequently in children. Today, PM is often encountered in temperate climates among HIV-infected individuals.

Why do Emergency Physicians need to keep PM on the radar?

PM is difficult to diagnose and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, namely, compartment syndrome, osteomyelitis, sepsis, and death.

Other, less common complications include endocarditis, septic emboli, pneumonia, pericarditis, septic arthritis, rhabdomyolysis, and brain abscess.

ED Clinical Presentation

- Gender: male > female

- Location:6

- Tropical disease: thigh > quadriceps

- HIV-infected population: deltoid > quadriceps > gluteal > iliopsoas

- What’s your differential diagnosis?

- Cellulitis, deep vein thrombosis, muscle strain, contusion, hematoma, osteomyelitis, thrombophlebitis, necrotizing fasciitis, appendicitis (if ileopsoas involvement).

There are three stages of PM as originally described by Chiedozi in 1979. Patients most commonly present during stage II.

Chiedozi Stages I-III7, 8

- Invasive stage (»1-2 weeks following hematogenous spread of infection): muscle cramping, myalgias, localized swelling, and low-grade fevers. This stage is often missed upon initial presentation.

- Purulent stage (»2-3 weeks following hematogenous spread): abscess formation. Muscle pain, tenderness, swelling, generalized malaise +/- systemic symptoms.

- Late stage (> 3 weeks following hematogenous spread): muscle destruction with local extension results in osteomyelitis and systemic bacteremia.

ED Evaluation

Labs:

- CBC: Leukocytosis with a left shift is common but does not occur in all patients.

- Inflammatory markers: ESR and CRP are typically elevated in later stages of the disease process with inflammation.

- Eosinophilia: May be present in immunocompetent patients.

- Creatinine kinase: Rarely, PM has been associated with rhabdomyolysis. In the vast majority of cases, CK will be within normal limits.

- Blood cultures: Blood cultures should be obtained in toxic patinets. If positive, blood cultures guide antibiotic therapy.

Imaging:

Ultrasound9-12

- The best ED screening tool to assess for PM.

- Pros: Rapid, radiation-sparing, and cost-effective.

- Cons: In early stages of the disease, ultrasound may fail to identify PM given the absence of fluid collection (abscess). As PM is typically a deep space infection, the depth of penetration of the high-frequency linear probe may limit visualization.

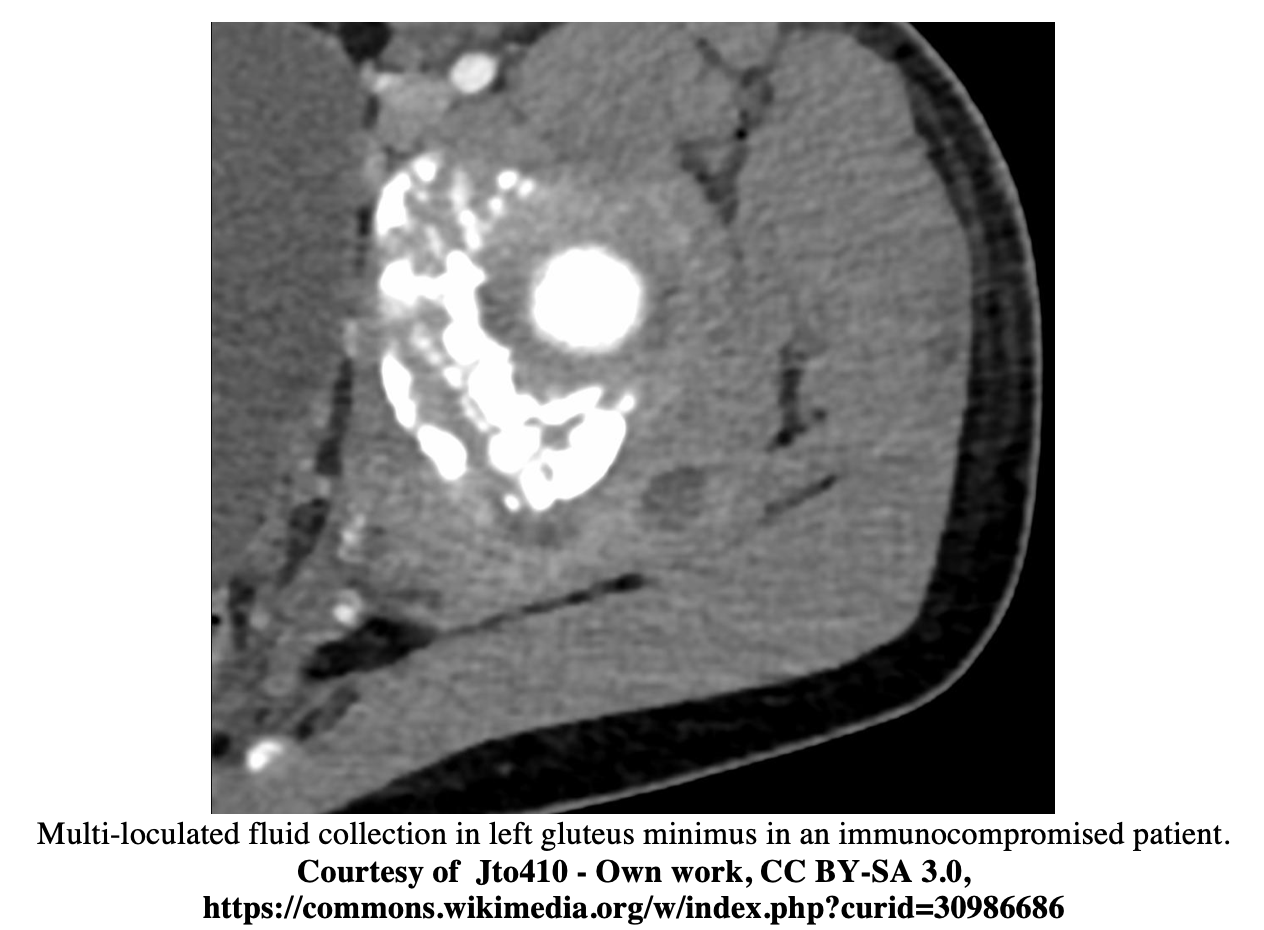

CT9,10,13

- CT may be utilized if MRI is not available. Due to unavailability of MRI in most institutions, CT is recommended.

- Con: Suboptimal differentiation of muscle edema versus abscess.

- Abscess appears as a rim-enhancing intramuscular fluid collection.

MRI9, 14, 15

- The diagnostic modality of choice for PM.

- Pro: Clearly demonstrates diffuse muscle inflammation and abscess formation while assessing the extent of tissue involvement (e.g. osteomyelitis).

- Cons: Time and costs associated with MRI performance.

- In the ED, this modality may not be available.

ED Management3, 8, 17, 18

Antibiotics: Empiric treatment should cover S. aureus. In immunocompromised individuals, consider targeting gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, and fungal pathogens. Suggested regimens include:

- Immunocompetent

- First line: Vancomycin (30 mg/kg IV daily divided over 2 doses, or up to 2 g)

- Second line:

- Daptomycin (4 mg/kg IV daily)

- Linezolid (600 mg IV BID)

- Ceftaroline (500 mg IV BID)

- Immunocompromised

- Vancomycin + beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor, or

- Vancomycin + 3rdgeneration cephalosporin 1g IV daily + metronidazole 500 mg IV TID)

- Second line:

- Fluoroquinolone + metronidazole

- Carbapenem

Consultation for Muscle Biopsy/Culture and Incision & Drainage: Interventional Radiology (IR) vs. General Surgery

- Muscle biopsy and culture is advised to guide antibiotic therapy.

- IR guided I&D, as compared to surgical I&D, has been associated with decreased hospital length of stay and duration of antibiotic therapy.16

Disposition

- Patients require admission with IV antibiotics until clinical improvement based on symptoms and hemodynamic status. Oral antibiotic therapy is continued on an outpatient basis for up to 6 weeks.19

Case

POCUS revealed a large fluid collection localized to right quadriceps muscle. MRI confirmed pyomyositis. IV antibiotic therapy was initiated, and the patient was admitted for IR-guided drainage.

Take Home Points

- In patients presenting with prolonged muscle pain, low-grade fevers, myalgias, and generalized fatigue, PM should be considered.

- Immunosuppression is a significant risk factor.

- PM most frequently results from aureus infection.

- Ultrasound may rapidly identify PM, but MRI is the diagnostic test of choice to determine the extent of the disease.

- IV antibiotics and I&D are the mainstays of treatment.

References/Further Reading:

- Bickels, J., Ben-Sira, L., Kessler, A. and Wientroub, S. (2002). Primary Pyomyositis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume, 84(12), pp.2277-2286.

- Crum, N. (2004). Bacterial pyomyositis in the United States. The American Journal of Medicine, 117(6), pp.420-428.

- Christin L. and Saraosi, G. (1992). Pyomyositis in North America: Case Reports and Review. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 15(4), pp.668-677.

- Exercise induced pyomyositis. (2012). BMJ, 345(Dec18 4), pp.e8516-e8516.

- Patel SR, Olenginski TP, Perruquet JL, Harrington TM. Pyomyositis: clinical features and predisposing conditions. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(9):1734-1738. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=9292796.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. “Bacterial Infections.” In Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 2020. Elsevier; Philadelphia. p. 252-290.e4.

- Chiedozi, L. (1979). Pyomyositis. The American Journal of Surgery, 137(2), pp.255-259

- Baddour LM, Keerasuntornpong A, Sullivan M. Pyomyositis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pyomyositis?source=history_widget. Published January 25, 2019.

- Agarwal V, Chauhan S, Gupta RK. Pyomyositis. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2011;21(4):975-983. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2011.07.011.

- Farrell G, Berona K, Kang T. Point-of-care ultrasound in pyomyositis: A case series. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;36(5):881-884. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.09.008.

- Tichter A, Riley DC. Emergency department diagnosis of a quadriceps intramuscular loculated abscess/pyomyositis using dynamic compression bedside ultrasonography. Critical Ultrasound Journal. 2013;5(1). doi:10.1186/2036-7902-5-3.

- Kumar MP, Seif D, Perera P, Mailhot T. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Diagnosing Pyomyositis: A Report of Three Cases. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;47(4):420-426. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.02.002.

- Gordon, B., Martinez, S. and Collins, A. (1995). Pyomyositis: characteristics at CT and MR imaging. Radiology, 197(1), pp.279-286

- Soler, R. (2000). Magnetic resonance imaging of pyomyositis in 43 cases. European Journal of Radiology, 35(1), pp.59-64

- Theodorou, S., Theodorou, D. and Resnick, D. (2007). MR imaging findings of pyogenic bacterial myositis (pyomyositis) in patients with local muscle trauma: illustrative cases. Emergency Radiology, 14(2), pp.89-96.

- Palacio EP, Rizzi NG, Reinas GS, et al. Open drainage versus percutaneous drainage in the treatment of tropical pyomyositis. Prospective and randomized study. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4799144/. Published November 17, 2015.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Executive Summary: Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444.

- Chiu S-K, Lin J-C, Wang N-C, Peng M-Y, Chang F-Y. Impact of underlying diseases on the clinical characteristics and outcome of primary pyomyositis. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2008;41:286-293.

- Annamalai A, Gopalakrishnan C, Jesuraj M, et al. Pyomyositis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2013; 89:179-180.