Author: Jordan Gipson, MD (EM Resident, San Antonio, TX) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 55-year-old male presents to your ED for voice changes. For the last few weeks he reports a nasal sound to his voice. He thought it would go away, but it seems to be getting worse. He also reports recent difficulty swallowing but does not have a sore throat.

On exam, the patient has normal vital signs. You note the patient is generally well appearing. When he speaks he has a nasal quality to his voice, and his tongue seems to be twitching. A focused neurologic exam demonstrates mildly reduced grip strength on the right hand compared to his left. His sensation is intact to both pin-prick and light touch.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

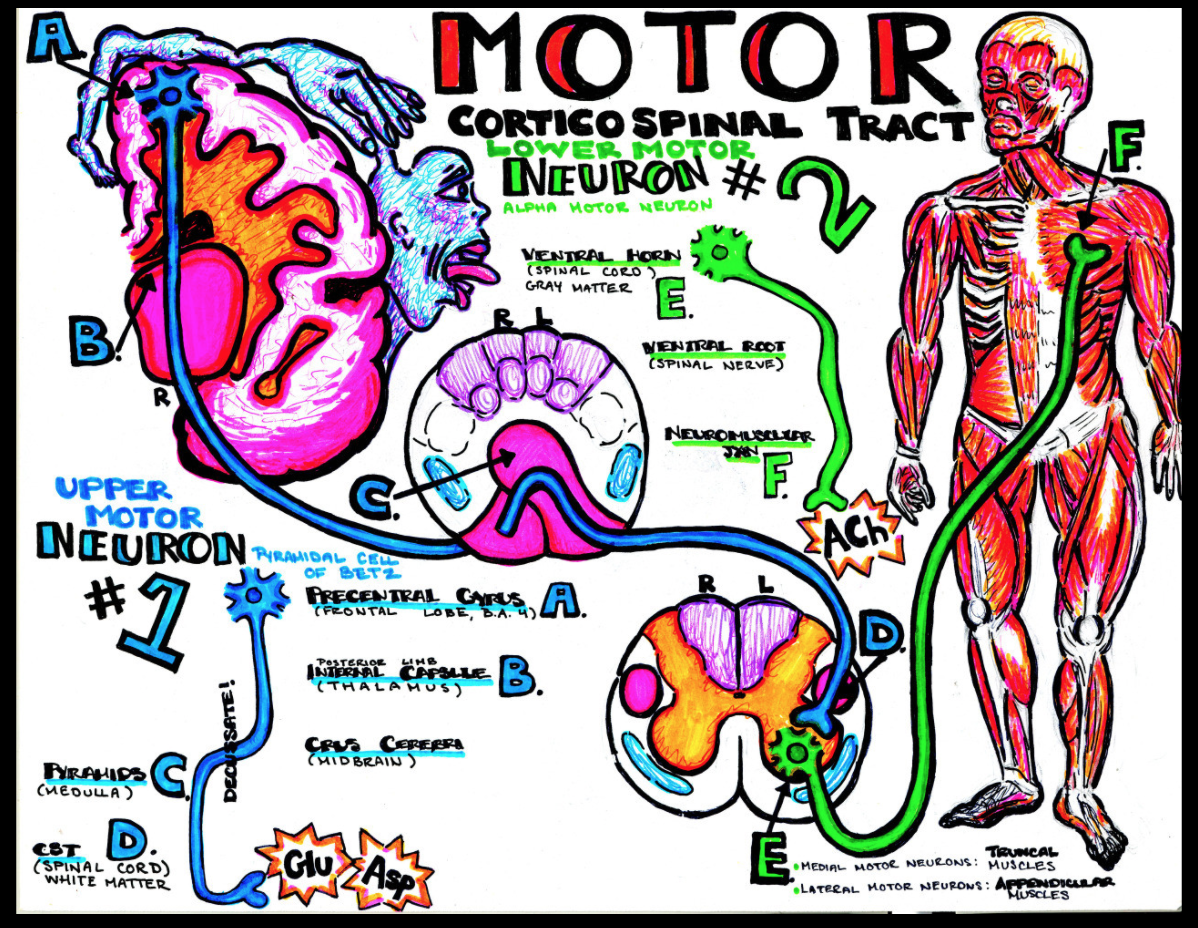

smArt Work – where the art of procrastination meets the study of medicine, by Dr. Katy Hanson. Please see more of Dr. Hanson’s amazing work at https://www.hansonsanatomy.com/download-my-notes

Background

ALS refers to a group of rare motor neuron disorders characterized by a spectrum of progressive weakness caused by degeneration of both upper motor neurons (UMN) and lower motor neurons (LMN). Patients with ALS gradually lose the ability to initiate and control voluntary movements. Most patients with ALS die from respiratory failure or aspiration pneumonia within 3-5 years from the onset of symptoms. Life expectancy in ALS is dependent on several factors, including phenotype, rate of disease progression, early presence of respiratory failure, and nutritional status.1-4

Epidemiology

ALS is a rare condition with incidence 2-3/100,000 people and prevalence 5/100,000.4,7 Despite its rarity, it is one of the most common motor neuron disease in adults. The mean age of onset is 60 years. Males are affected 1.5X compared to females. ALS is categorized as either sporadic or familial. The sporadic form is most common and affects 90-95% of patients with the disease, with familial the remaining 5-10%. There are also geographical areas of concentration (with rates 50–100 times higher than the general population). These populations are found in parts of Japan, Guam, and South West New Guinea. It is believed that the increased incidence of ALS in these regions may be due to local environmental factors.3

Pathogenesis

The exact cause for ALS is unknown. Multiple theories for the pathogenesis of motor neuron cell death in ALS have been proposed including glutamate excitotoxicity, mitochondrial abnormalities, axonal structure or transport defects, and free radical-mediated oxidative stress.3 Gross pathological specimens demonstrate frontal cortical atrophy, degeneration of corticospinal and spinocerebellar tracts, and degeneration of motor neurons in the cervical and lumbar spine.2,5,6 It is likely that more than one mechanism contributes to the development of ALS.

What are the clinical features of ALS?

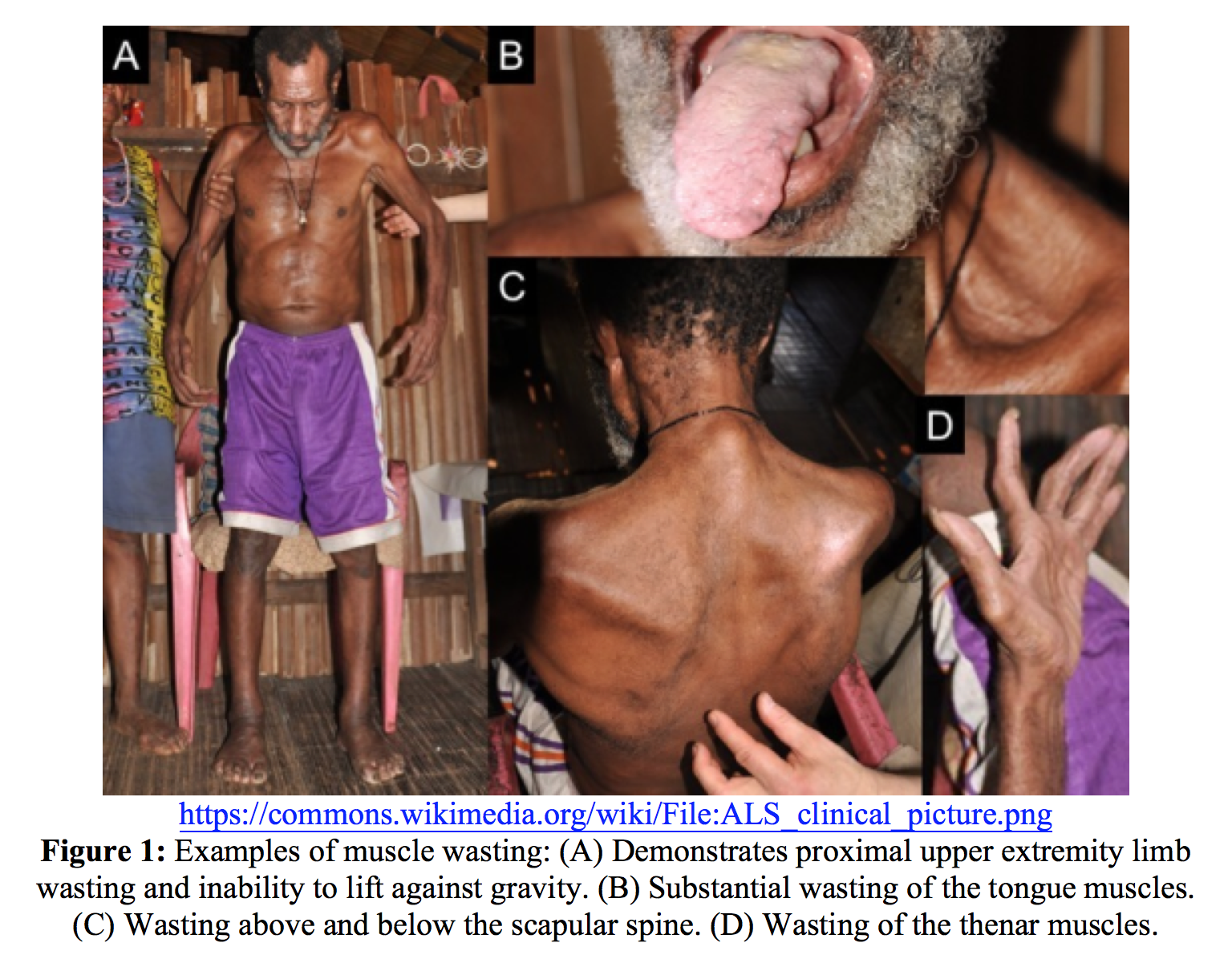

The hallmark feature of ALS is progressive dysfunction of upper and lower motor neurons. Evaluation to identify UMN and LMN lesions should be performed by anatomical segment. UMN signs include spasticity, hyperreflexia, and retained reflexes in an otherwise weak limb. LMN signs and symptoms include muscle weakness, atrophy (Figure 1), and fasciculations.3

ALS has several distinct phenotypes and may present in various ways. In order of prevalence ALS may present as limb-onset; bulbar-onset; primary lateral sclerosis with pure UMN involvement; and progressive muscular atrophy, with pure LMN involvement. ALS most commonly starts as unilateral limb onset with rostrocaudal and contralateral spread, eventually involving all other limbs. 20-30% of patients present with bulbar onset ALS.1,7 Bulbar symptoms include speech disturbances, dysphagia for solids and liquids, and excessive drooling (sialorrhea) which is due to difficulty swallowing secretions and lower facial weakness. Bulbar UMN signs include an exaggerated gag reflex, snout reflex, or forced yawns. An even smaller proportion may present with respiratory involvement or with symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

Patients with ALS experience a wide variety of symptoms including fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, excessive drooling, bronchial secretions, muscle cramps, and pain. They have difficulty managing their nutrition due to dysphagia, weakness, and chronic constipation. ALS is associated with psychiatric conditions of pseudobulbar affect, depression, anxiety, and insomnia. There is a significant portion of patients with ALS who go on to develop symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

Diagnostic Approach and Differential Diagnosis:

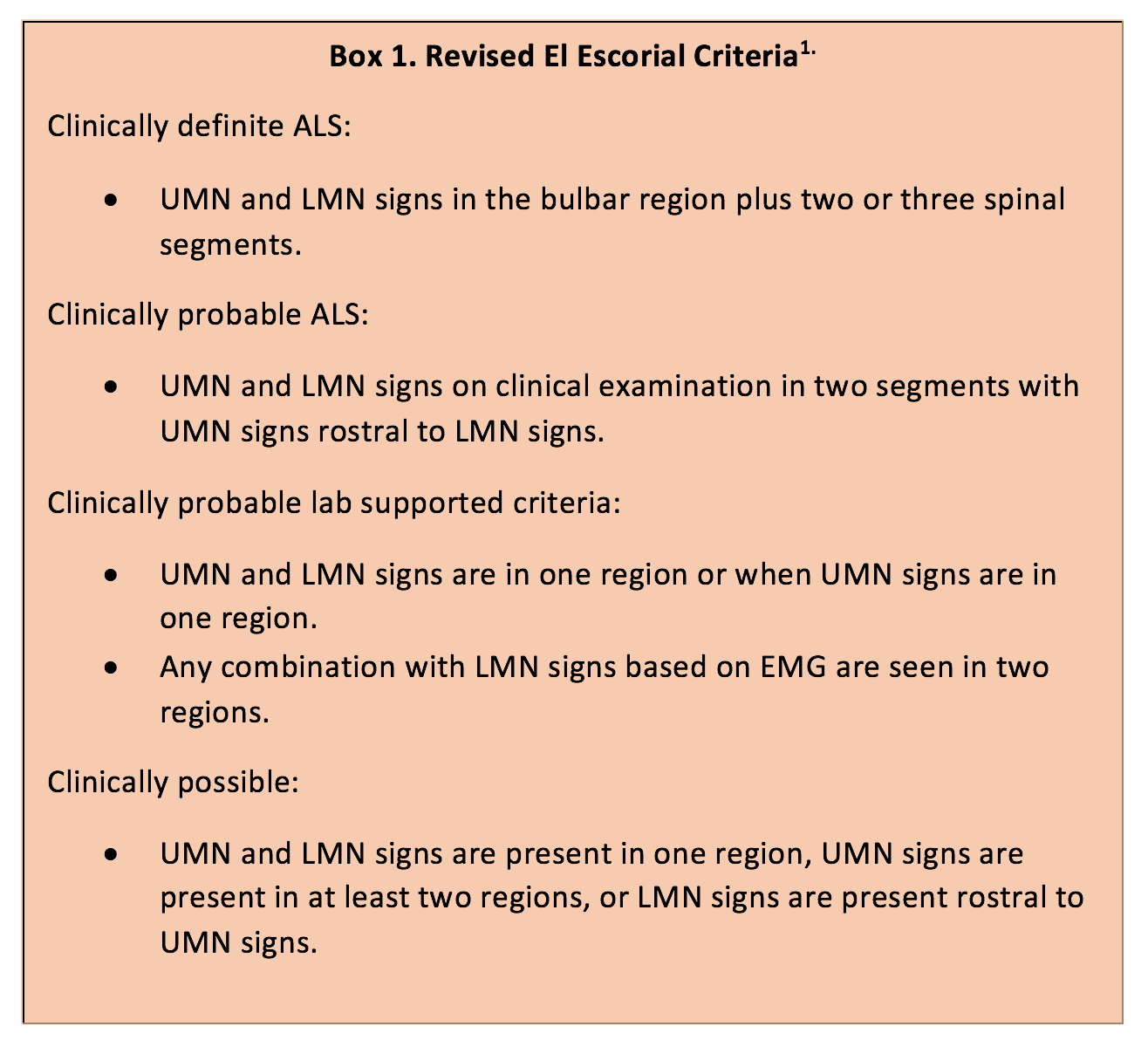

The clinical diagnosis of ALS is suggested when there is evidence of progressive UMN and LMN dysfunction without other CNS dysfunction or alternative explanation. However, there is no definitive diagnostic test for ALS. Scoring systems such as the revised El Escorial criteria (Box 1), which use a combination of UMN and LMN, may help establish levels of diagnostic certainty. However, these scoring systems tend to have poor sensitivity early in the disease process.7 Also, there is a wide variety of conditions which mimic ALS including diabetes, dysproteinemia, endocrinopathies, vitamin deficiencies, heavy metal toxicity, vasculitis, CNS and spinal cord tumors, and other inflammatory neuropathies.1

Patients who present to the ED with signs/symptoms suggestive of ALS should receive a screening evaluation and be referred to a neurologist for further workup. Patients with respiratory distress will require resuscitation and admission. Prior to being diagnosed with ALS, a comprehensive diagnostic workup should be performed to evaluate for the disease and exclude treatable conditions. The median time to diagnosis from the onset of symptoms is 14 months due to the broad differential, the variety of ALS phenotypes, and the complexity of diagnosing ALS.2

Case continued

Two years later the same patient is brought to your ED by EMS for dyspnea. His wife arrives with him and states he is less responsive than his baseline. The patient does not have the ability to speak, but prior to today he had been able to communicate with use of an assistance device.

On exam his vital signs are within normal limits. He is unable to verbally communicate. He is frail in appearance and has lost about 70lbs since you last saw him. He is unable to take a deep breath and is now severely weak in all extremities.

You obtain a venous blood gas which is notable for a PaCO2 of 75. You realize the patient is experiencing respiratory failure, and you wonder what your next step should be.

How is ALS managed?

There is no cure for ALS, but there are treatments which slow progression and provide symptomatic relief. ALS is best managed with an emphasis on symptomatic treatment strategies which focus on enhancing quality of life and maintaining patient autonomy. ALS treatment should include a multidisciplinary approach to include neurologist, physical and occupational therapists, dietician, and social worker.8

Riluzole, an inhibitor of glutamate release, has been shown to prolong survival by 3-6 months.3,9 In May of 2017, edaravone, an intravenous free radical scavenger, was granted orphan drug designation by the FDA. In small clinical trials, patients who were treated with edaravone had slower disease progression.10,11

Pain is a common problem in patients with motor neuron disease which is associated with reduced joint mobility, muscle cramps, and skin pressure sores due to immobility. It is recommended that treating physicians follow the 1990 World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder to manage pain in these patients. First line treatments for pain should include acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The physician should exercise caution with the use of opioids in patients with ALS due to the inhibitory effects on ventilation.12

What are common emergent presentations of ALS?

It is important for the emergency physician to recognize clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of ALS in the rare event that a patient initially presents to the ED prior to receiving the diagnosis. There are case series of patients who are not diagnosed until they present with respiratory failure requiring intubation.13,14 However, most patients with ALS who present to the ED will already be diagnosed and may arrive with a new or worsening complication of their disease. Emergent presentations include acute respiratory failure, aspiration pneumonia, choking episodes, and trauma related to extremity weakness. Most deaths from ALS are due to respiratory failure with or without pneumonia. Blood gas determination does not reliably predict impending respiratory failure. A forced vital capacity < 25 mL/kg, or a 50% decrease from predicted normal, increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia and respiratory failure. Hospital admission is indicated for impending respiratory failure, pneumonia, inability to control oral secretions, or to facilitate long-term placement for declining overall status.2

When should ventilatory support be initiated?

Important issues such as long term respiratory management should be discussed with the patient as early as possible. The decision of whether to undergo a tracheostomy for long-term mechanical ventilation is a personal one which is faced by all patients. This choice may be postponed using non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV).

NIV has been shown to reduce symptoms, prolong life, and potentially improve quality of life.8,9,16 The decision to initiate NIV should be based on a combination of respiratory muscle weakness and respiratory symptoms. NIV should be started when a patient is experiencing symptoms of fatigue, dyspnea, or morning headache in combination with hypercapnia with PaCO2 greater than or equal to 45 mm Hg, nocturnal oxygen saturations less than 88%, or pulmonary function testing with mean inspiratory pressure <-60 cm H2O or forced vital capacity less than 50%. All unstable patients should be admitted to the hospital for NIV initiation.

In almost all cases oxygen should administered in conjunction with NIV. Oxygen therapy alone has been shown to worsen respiratory symptoms as well as carbon dioxide retention in patients with ALS.15,17

Tracheostomy with mechanical ventilation should be considered with symptoms of respiratory failure in patients who are intolerant of NIV or fail NIV. Ideally this is an elective procedure which is performed after discussion with the patient so the patient can make an informed decision and outline advanced directives. However, tracheostomies are often initiated in emergent situations. These emergent tracheostomies are often performed in patients who do not have advanced directive and are less likely to receive information about impending respiratory failure. Some patients put off the decision upon elective tracheostomy until acute respiratory failure develops.15

End-of-Life Issues

End-of-life counseling is an important component of patient care. The goal of decision making is to empower patients and respect his/her autonomy. End of life decision making should reflect the patient’s quality of life goals and may help avoid undesired interventions such as emergency tracheostomies.1. For the patient to make an informed decision, he/she needs sufficient information pertaining to the disease process and the treatment options available. The patient should feel supported in their decision. An adequate amount of time is usually needed to consider the many choices prior to making the decision.

Important areas of decision making in ALS include initiation of invasive interventions such as gastrostomy or tracheostomy placement as well as end-of-life planning. Advanced care plans made early in the disease course of ALS are helpful, as they can ensure the person’s wishes are understood even if he/she is unable to communicate or there is a loss of capacity. Through all decisions and interventions, it is important to stress that supportive care will continue to be provided with the aim of managing symptoms and minimizing discomfort.18

Take Home Points

- ALS is a progressive, degenerative disease which leads to paralysis and respiratory failure. It inevitably results in death, usually within 3-5 years from the onset of symptoms.

- ALS has a variety of phenotypes, and it is important for the emergency physician to recognize the various ways the disease can present and to refer patients with signs/symptoms of the disease to a neurologist for further testing.

- Bilevel positive pressure ventilation has been shown to reduce symptoms, prolong life, and improve quality of life in patients with ALS.

- Patients with ALS should have relatively normal lung function and generally do not require supplemental oxygen unless a secondary process is present. Supplemental oxygen should be administered concurrently with NIV when it is needed.

- ALS treatment strategies should focus on symptomatic treatment and should serve to enhance quality of life while maintaining patient autonomy.

Other resources for providers and patients:

https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Amyotrophic-Lateral-Sclerosis-ALS-Information-Page

References/Further Reading:

- Goutman SA. Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2017;23:1332-1359. doi:10.1212/con.0000000000000535.

- Handel DA, Gaines S. Chronic Neurologic Disorders. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(22):1688-1700. doi:10.1056/nejm200105313442207.

- Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, et al. A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surgical Neurology International (Rowland LP & doi:10.1056/nejm200105313442207.)l. 2015;6:171. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.169561.

- Ellison D, Love S, Chimelli L, et al. Ch 27 Motor Neuron Disorders. In: Neuropathology: a reference text of CNS pathology. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2013.

- Deng H-X, Zhai H, Bigio EH, et al. FUS-immunoreactive inclusions are a common feature in sporadic and non-SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annals of Neurology. 2010. doi:10.1002/ana.22051.

- Kiernan, M., Vucic, S., Cheah, B., Turner, M., Eisen, A., Hardiman, O., Burrell, J. and Zoing, M. (2011). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The Lancet, 377(9769), pp.942-955.

- Berg JPVD, Kalmijn S, Lindeman E, et al. Multidisciplinary ALS care improves quality of life in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2005;65(8):1264-1267. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000180717.29273.12.

- Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice Parameter update: The care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1218-1226. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc0141.

- Nagase M, Yamamoto Y, Miyazaki Y, Yoshino H. Increased oxidative stress in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the effect of edaravone administration. Redox Report. 2016:1-9. doi:10.1179/1351000215y.0000000026.

- Commissioner of the Press Announcements – FDA approves drug to treat ALS. U S Food and Drug Administration Home Page. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm557102.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

- Ng L, Khan F, Young CA, Galea M. Symptomatic treatments for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. October 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011776.pub2.

- Sato K, Morimoto N, Deguchi K, Ikeda Y, Matsuura T, Abe K. Seven amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients diagnosed only after development of respiratory failure. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2014;21(8):1341-1343. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2013.11.021.

- Shoesmith CL, Findlater K, Rowe A, Strong MJ. Prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with respiratory onset. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2007;78(6):629-631. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.103564.

- Gruis KL, Lechtzin N. Respiratory therapies for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A primer. Muscle & Nerve. 2012;46(3):313-331. doi:10.1002/mus.23282

- Annane D, Orlikowski D, Chevret S. Nocturnal mechanical ventilation for chronic hypoventilation in patients with neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001941.pub3.

- Gay PC, Edmonds LC. Severe Hypercapnia After Low-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Patients With Neuromuscular Disease and Diaphragmatic Dysfunction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1995;70(4):327-330. doi:10.4065/70.4.327.

- Oliver DJ, Turner MR. Some difficult decisions in ALS/MND. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 2010;11(4):339-343. doi:10.3109/17482968.2010.487532.