Anxiety: What do you need to consider?

- Jul 5th, 2017

- Ashley Werbin

- categories:

Author: Ashley Werbin, DO (Resident Physician at SAUSHEC, USAF) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UT Southwestern Medical Center / Parkland Memorial Hospital) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or policy of the Department of Defense or its Components.

Case

A 55-year-old male with a previous medical history significant for hypertension and diabetes presents to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of chest discomfort and shortness of breath. The patient reports the onset of his symptoms to be about one hour ago while at dinner with family. Review of systems is remarkable for palpitations and generalized weakness. The patient denies nausea, dizziness/lightheadedness, headache, and history of blood clots. As you review his vital signs, the patient states he has had this feeling before and was diagnosed with anxiety.

Triage Vital Signs: T 98.7°F; HR 122; BP 142/81; RR 16; SpO2 98%RA

Although difficult to resist the inclination to assume it is a recurrence of his anxiety, you must first eliminate the possibility of life-threatening conditions. Because no lab test or imaging study can definitively diagnose anxiety and there are numerous medical conditions that mimic anxiety, a complete and thorough history and physical examination are needed.

Epidemiology of Anxiety

According to the CDC, anxiety remains the most common mental health diagnosis in the general population-characterizing 18.1% of all adults in the United States.1,2 The innumerable and non-specific symptoms that patients experience associated with anxiety and panic attacks combined with the limited accessibility for some to primary care is one of the reasons for the exponential increase in mental health-related ED visits. Between the years 1992 and 2003, mental health-related ED visits increased by 75%, with 26.1% of these being anxiety-related.3,4 Between the years 2006 and 2013, this rate has continued to climb by 15%.2

Although stress, anxiety, and depression are diagnostic codes in 61% of mental health disorder related ED visits and one in eight visits involve mental and substance use disorders, patients with mental illnesses tend to have serious underlying chronic medical conditions that should not be overlooked.2,3,5 As stated in the “Emergency Psychiatric Assessment” chapter in the second edition of Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials, “approximately 50% of patients seeking psychiatric emergency services have a poorly treated or undiagnosed medical condition contributing to their symptoms.”6 The following is information to help identify red flags in the patient presenting with anxiety-like symptoms in an effort to diagnose and treat life-threatening disorders.

A Review of Anxiety

Pathophysiology

While the exact etiology of anxiety is not explicit, several theories involving the release of certain hormones and neurotransmitters have been suggested.7,8 A stressor is defined by any disruption in the body’s perceived homeostasis, causing a cascade of hormonal events.9 These hormones alter the serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems leading to the feelings and symptoms of anxiety.8

Although not the only mechanism by which this occurs, the release of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) from the hypothalamus initiates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, generating the release of corticotropin (from the pituitary), followed by the discharge of glucocorticoid and epinephrine (from the adrenal cortex).7,9 Under normal circumstances this sequence is controlled by negative feedback; however, once an individual experiences a physiologic change in homeostasis or emotional arousal, hyperactivation of the autonomic nervous system occurs.9 Dopamine and g-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are presumed to have some involvement, as well.7,10

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of anxiety include dizziness/unsteadiness/lightheadedness, headache, paresthesias, amnesia, fatigue, restlessness, emotional lability, irritability, chest pain or discomfort, palpitations/tachycardia, sensations of shortness of breath or smothering/dyspnea, tachypnea, nausea or abdominal upset, muscle tension, chills or hot flushes, diaphoresis, trembling/shaking, and dry mouth.7,8

Diagnosis and Treatment (Recommendations)

As mentioned previously, there is no lab test or imaging study to definitively diagnose anxiety. However, psychiatrists utilize the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) to make a clinical diagnosis after emergent organic causes of psychiatric crisis have been considered.

According to the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the following are clinical recommendations for the treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Panic Disorder (PD):

Level A Recommendation

– Psychotherapy is as effective as medication for GAD and PD with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) having the best evidence11

Level B Recommendations

– Physical activity is a cost-effective treatment for GAD and PD11

– Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor’s (SSRI’s) are considered first line therapy for GAD and PD11

– Antidepressants + Benzodiazepines are quick treatments, but do not improve longer term outcomes11

The above treatments, while Level A and Level B recommendations, are not entirely practical in the ED. With an acutely agitated or moderately anxious patient, therapies that possess quick onsets of action are the most useful. Benzodiazepines are the recommended first-line medications for the short-term management of anxiety.7,8

In those patients with milder anxiety symptoms, oral benzodiazepines (clonazepam 0.25mg or alprazolam 0.50mg) are suggested.7 If symptoms are more severe, benzodiazepines can be given intravenously in the following doses: lorazepam 0.50-1 mg or diazepam and midazolam in 1-2 mg increments.7

Medical Mimics of Anxiety

Certain medical conditions and medications mimic, manifest, produce, or exacerbate anxiety, which makes it difficult to distinguish anxiety from pathologic derangements.7 Despite this challenge, emergency physicians must be able to recognize and act quickly with regard to the medical mimics of anxiety that are time-sensitive. These life-threatening conditions will be reviewed below and are organized by body system.

Neurologic

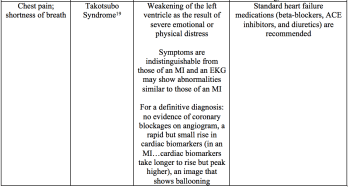

Cardiac

Pulmonary

Endocrine/Metabolic

Toxin

The Emergency Department Approach

Not only can the above conditions emulate anxiety, but infection, electrolyte abnormalities, and medication withdrawal also have the potential to manifest similar signs and symptoms. When addressing the patient presenting to the ED with complaints of chest discomfort, shortness of breath, and tachycardia (among others previously mentioned), the emergency physician should:

- Assess the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulatory status, intervening when necessary.

- Resuscitate and address hemodynamic instability and ABC’s.

- Perform a focused history regarding medical comorbidities, the onset and duration of symptoms, and current medication/drug use.

- Perform a focused physical exam including HEENT, cardiac, pulmonary, GI, extremities, and neurologic systems. Always assess patient mental status and evaluate closely for abnormality.

- Utilize the history and physical, as well as other ancillary studies to make educated decisions regarding further evaluation, treatment, and disposition.

- ECG, electrolytes, TSH, targeted toxicologic testing (salicylates, acetaminophen, chest x-ray (if pulmonary/cardiac symptoms present), and urine may be helpful.

Key Points

- Perform a focused history and physical exam by first addressing the stability of the patient’s condition (ABCs).

- Due to numerous presentations of anxiety, it is important to evaluate and differentiate from a medical emergency.

- Medical => 1st presentation of symptoms occurs at age >40, possible fluctuation of consciousness, and autonomic instability.27

- Anxiety => 1st presentation of symptoms occurs between ages 18-45, family history of anxiety, patient is concerned about losing control, and occurrence of recent/anticipated life event.27

- Do not hesitate ordering a cardiac work-up in a patient presenting with cardiovascular symptomatology, checking a screening TSH in a patient presenting with complaints of anxiety,27 or obtaining focused toxicologic testing.

- Benzodiazepines are the recommended short-term management option (clonazepam 0.25mg or alprazolam 0.50mg).

References/Further Reading:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Burden of Mental Illness. 2013. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics/burden.htm

- Weiss, A.J., Barrett, M.L., Heslin, K.C. and Stocks, C. Trends in Emergency Department Visit Involving Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2006-2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical Brief 216. December 2016.

- Bazelon, D.L. Increased Emergency Room Use by People with Mental Illnesses Contributes to Crowding and Delays. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. Available from: http://www.bazelon.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=Epvwc7WBOHg%3D&tabid=386

- Owens, P.L., Mutter, R. and Stocks, C. Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits among Adults, 2007. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical Brief 92. July 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Emergency Department Visits by Patients with Mental Health Disorders-North Carolina, 2008-2010. June 14, 2013.

- Char, D.M. The Emergency Psychiatric Assessment. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013:1691-1626

- Kang, C.S. and Harrison, B.P. Anxiety and Panic Disorders. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013:1644-1647

- Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education. Anxiety Disorders. 2010. Available from: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/psychiatry-psychology/anxiety-disorder/

- Shelton, C.I. Diagnosis and Management of Anxiety Disorders. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2004;104.

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Implementation. Pathway: Benzodiazepine Pathway, Pharmacodynamics. Available from: https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA165111376#tabview=tab0&subtab=v.

- Locke, A.B., Kirst, N. and Shultz, C.G. Diagnosis and Management of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults. American Family Physician. 2015; 91(9):617-624.

- Epilepsy Foundation. Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. 2013. Available from: http://www.epilepsy.com/ learn/types-epilepsy-syndromes/temporal-lobe-epilepsy

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Myasthenia Gravis. Available from: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/nervous_system_disorders/myasthenia_gravis_85,P07785/

- Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Emergency Management of Myasthenia Gravis. Available from: http://www.myasthenia.org/HealthProfessionals/EmergencyManagement.aspx

- Jani-Acsadi, A. and Lisak, R.P. Myasthenic crisis: Guidelines for prevention and treatment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2007;127-133.

- Hals, G. and McCoy, C. Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Review for the Practicing Emergency Physician. Emergency Medicine Reports. 2015. Available from: https://www.ahcmedia.com/articles/135666-supraventricular-tachycardia-a-review-for-the-practicing-emergency-physician

- Eken, C., Oktay, C., Bacanli, A., Gulen, B., et al. Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Patients Presenting with Chest Pain to the Emergency Department: A Comparison Between Cardiac and Non-Cardiac Origin. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010; 39(2):144-150.

- Kuo, D.C. and Peacock F.W. Diagnosing and managing acute heart failure in the emergency department. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine. 2015; 2(3):141-149.

- Harvard Health Publications. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (broken-heart syndrome). 2010. Updated in 2016. Available from: http://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/takotsubo-cardiomyopathy-broken-heart-syndrome

- Camargo, C.A., Rachelefsky, G. and Schatz, M. Managing Asthma Exacerbations in the Emergency Department. Annals of American Thoracic Society. 2009; 6(4):357-366.

- Rowe, B.H., Bhutani, M., Stickland, M.K. and Cydulka, R. Assessment and Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the Emergency Department and Beyond. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2011; 5(4):549-559.

- Evensen, A.E. Management of COPD Exacerbations. American Family Physician. 2010; 5:607-613.

- Church, A. and Tichauer, M. The Emergency Medicine Approach To The Evaluation and Treatment Of Pulmonary Embolism. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2012; 14.

- Finlayson, C. and Zimmerman, D. Hyperthyroidism in the Emergency Department. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2009; 10(4):279-284.

- Carroll, R. and Matfin, G. Endocrine and metabolic emergencies: thyroid storm. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010; 1(3):139-145.

- Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Condition: Carcinoid syndrome. 2015. Available from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/carcinoid-syndrome/basics/treatment/con-20027127

- Elmore, K.E. and Schenider, R.K. Medical Mimics of Anxiety Disorders. 2001. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.536.7931&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Garg, M.K., Kharb, S., Brar, K.S., Gundgurthi, A., et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: Role of the endocrinologist. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011; 15:329-336.

- Addisonian Crisis (Acute Adrenal Crisis). 2017. Available from: http://www.healthline.com/health/acute-adrenal-crisis#overview1

- Pimstome, N.R., Anderson, K.E. and Freilich, B. Emergency Room Guidelines for Acute Porphyrias. American Porphyria Foundation. Available from: http://www.porphyriafoundation.com/for-healthcare-professionals/emergency-guidelines-for-acute-porphyria

- Zosel, A.E. General Approach to the Poisoned Patient. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1221-1230.

- Fulton, J.A. and Nelson, L.S. Anticholinergics. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1239-1245.

- Calzada-Jeanlouie, M. and Chan, G.M. Sympathomimetics. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1280-1285.

- Long, H. Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and NSAIDs. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1231-1238.

- Mycyk, M.B. Toxic Alcohols. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1292-1298.

- Lank, P.M. and Kusin, S. Ethanol and Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal. In: Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. 2013; 1314-1322.