Authors: Kyle Smiley, MD (EM Resident Physician, San Antonio, TX) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit, EM Attending Physician) // Reviewed by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital); Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Northwell, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 37-year-old G5P4 at 33 weeks presents to the ED after being brought in by ambulance. She had a precipitous delivery while the ambulance was pulling in. The newborn is doing well, but the mother is complaining of shortness of breath and chest pain.

Triage vital signs (VS) include BP 88/45, HR 121, T 97.1, RR 28, SpO2 89% on 6L NC. On exam, she appears pale and anxious. She is tachycardic and tachypneic with diffuse wheezing and rhonchi. You notice precipitous vaginal bleeding and blood oozing from her IV site.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Amniotic fluid embolism

Epidemiology:

- Incidence of 1:15,200 to 1:53,4001

- 7% occur during labor

- Causes approximately 14% of all maternal peripartum death in United States

- Current fatality rate 13-60%1-4

- Risk factors: Advanced maternal age, amniocentesis, cesarean delivery, eclampsia, medical induction of labor, placental pathology, diabetes, infection, cervical and uterine pathology such as uterine rupture, blunt abdominal trauma, multiparity, trauma1,2,4

- Protective factors: Maternal age <20 years1,2,4

Pathophysiology:

- Mechanism unclear

- Proposed that amniotic fluid and/or fetal material enter maternal circulation during uterine manipulation or delivery1

- Theories include direct complement activation, immunologic reactivity

- Causes DIC, right heart strain followed by left heart strain

Clinical Presentation:

- Subjective: feeling of impending doom, chest pain, pins and needles sensation, nausea, lightheadedness1

- Physical exam: Hypotension, dyspnea, hypoxia, pulmonary edema/ARDS, cyanosis, bleeding from IV sites/mucous membranes, altered mental status, fetal distress, seizures1-5

Evaluation:

- Labs

- CBC, CMP, ABG, Coagulation panel, TEG if available, cardiac enzymes, type and screen, d-dimer

- Anemia, leukocytosis, prolonged PT and aPTT, decreased fibrinogen level

- Suggests DIC6

- Hypoxemia on ABG

- Thrombocytopenia is rare

- Patients often need transfusions to correct massive hemorrhage and coagulopathy

- Anemia, leukocytosis, prolonged PT and aPTT, decreased fibrinogen level

- No diagnostic biomarker has been discovered3

- CBC, CMP, ABG, Coagulation panel, TEG if available, cardiac enzymes, type and screen, d-dimer

- EKG

- ST segment and T wave abnormalities in early phase

- Arrhythmias or asystole in late phase

- Imaging

- Chest X-ray

- POCUS of lungs

- B lines

- POC echocardiogram

- Right heart failure with bowing of interatrial and interventricular septum into left heart1,3-5

- Severe pulmonary hypertension

Treatment:

- ABCs

- Provide supplemental oxygen

- Low threshold to intubate

- Supporting cardiac output

- Place patient in left lateral decubitus

- Optimize preload

- Fluid resuscitate based on volume status

- Blood transfusion or activation of massive transfusion protocol if patient having postpartum hemorrhage

- Administer vasopressors for hypotension (norepinephrine)

- Milrinone and dobutamine for inotropy

- Controlling hemorrhage, if present3-5

- Uterine massage, manual uterine sweep for retained products of conception

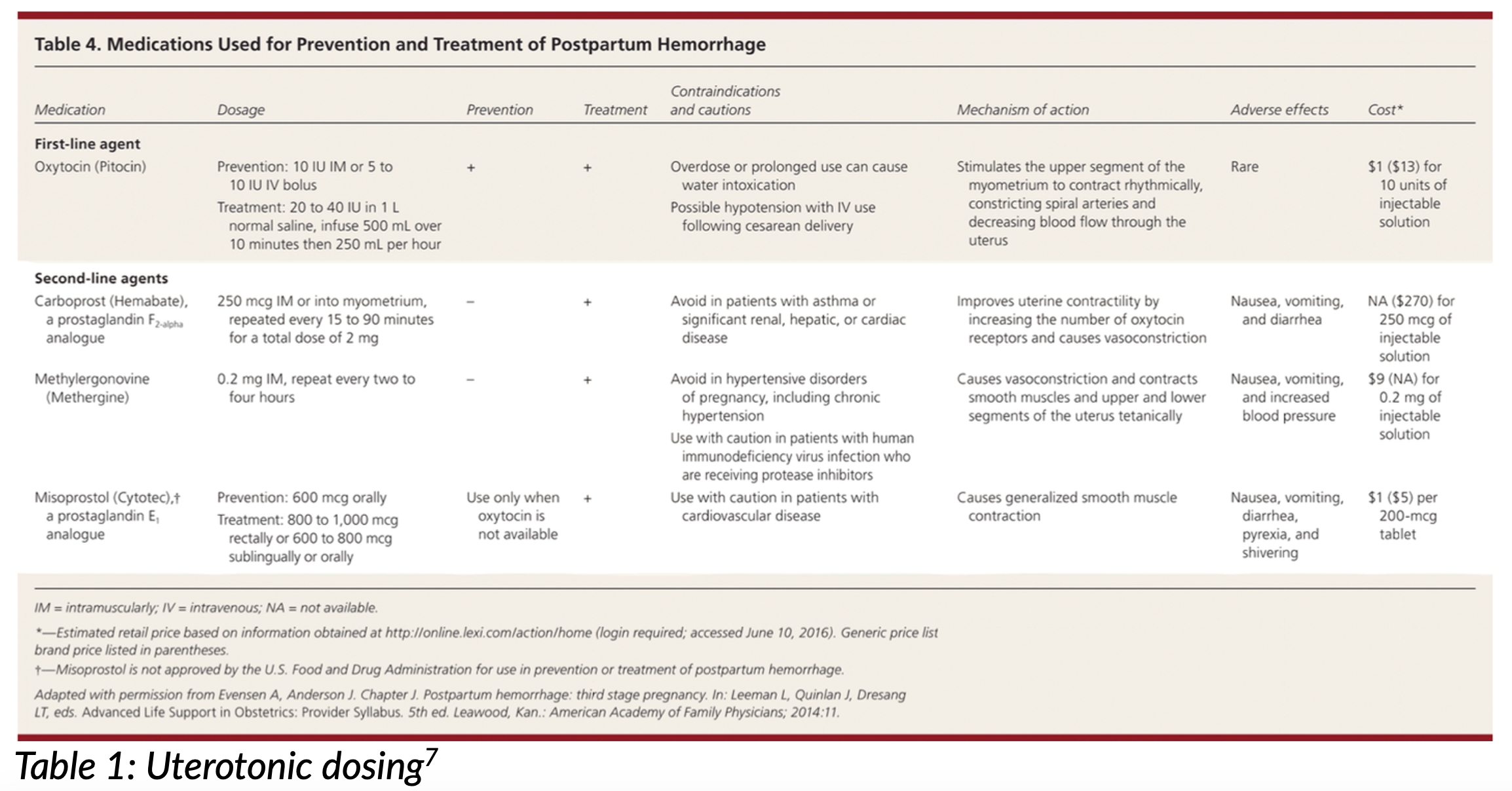

- Uterotonics7 (Table 1)

- Oxytocin

- Carboprost

- Avoid in asthmatics

- Methylergonovine

- Avoid in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

- Misoprostol

- TXA 2g IV

- Reversal of coagulopathy6

- Cryoprecipitate is preferred—1 unit per 5-10 kg of body weight

- May substitute with FFP or platelets if cryoprecipitate is not available

- Recombinant factor VIIa is newer proposed treatment8

- Adjunct medications9

- A-OK acronym

- Atropine 1 mg IV for bradycardia (HR <60 BPM)

- Ondansetron 8 mg IV blocks serotonin receptors and reduces release of inflammatory mediators

- Ketorolac 30mg IV blocks thromboxane production, reducing coagulopathy

- Deliver fetus if >22 weeks gestation

- Resuscitative cesarean is indicated in event of cardiopulmonary arrest

- Treat potentially viable neonate according to Neonatal Resuscitation Protocol

- A-OK acronym

Disposition:

- Early consults to ICU, OB, neonatology and anesthesia during stabilization

- Patient may require OR for cesarean delivery or hysterectomy

- Patient may require IR for uterine artery embolization or thrombectomy prior to ICU admission

- If neonate is present, will likely require NICU admission

Pearls:

- Amniotic fluid embolism is a rare diagnosis with high mortality rate

- Anticipate critical illness and resuscitate ABCs with emphasis on cardiac output, hemorrhage control, and reversal of coagulopathy

- Consult specialists early (see above)

A 32-year-old woman, G2P1, presents to the ED via EMS after having a precipitous delivery of a healthy newborn in the ambulance and now sudden respiratory distress, hypotension, and altered mental status. According to EMS, she was in labor at home and delivered the newborn shortly after they had loaded her into the ambulance. Her respiratory symptoms developed approximately 10 minutes later. Her vital signs show a blood pressure of 70/40 mm Hg, heart rate of 140 bpm, respiratory rate of 30/min, and oxygen saturation of 85% on room air. She becomes unresponsive shortly after arrival. What is the most likely diagnosis?

A) Amniotic fluid embolism

B) Eclampsia

C) Placental abruption

D) Pulmonary embolism

Answer: A

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of pregnancy. AFE should be considered in a patient who experiences cardiorespiratory collapse during labor or shortly thereafter. There are no specific laboratory tests that confirm the presence of AFE, so this is a clinical diagnosis. Common manifestations include hypoxia, hypotension, respiratory distress, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and cardiac arrest, and this condition frequently leads to death. Most cases occur during labor but may also occur during vaginal or cesarean delivery. The pathophysiology of AFE is not well understood, but it appears that a disruption to the interface between maternal and fetal circulation allows amniotic fluid to enter maternal circulation, which leads to pulmonary vasoconstriction and mechanical obstruction by amniotic fluid debris. If AFE occurs during labor, immediate delivery is recommended. Treatment is supportive with respiratory therapy, critical care, inotropic therapy, and cardiac life support.

Eclampsia (B) is characterized by the onset of seizures in a woman with preeclampsia (hypertension and proteinuria), but it typically does not present with the sudden onset of respiratory distress and profound hypotension described here. The absence of preeclampsia symptoms prior to the acute event makes eclampsia less likely.

Placental abruption (C) involves the premature separation of the placenta from the uterine wall and can lead to significant maternal bleeding and fetal distress. However, it does not typically present with the sudden cardiovascular and respiratory collapse seen in this patient. Furthermore, the newborn has already been delivered, and the placenta should separate from the uterus.

While pulmonary embolism (PE) (D) can cause sudden respiratory distress and hypotension, it is less commonly associated with the dramatic cardiovascular collapse and rapid progression to unresponsiveness seen in AFE. Additionally, PE in the context of labor is less likely than AFE, given the patient’s presentation and timing.

Further Reading:

FOAM Reading:

References:

- Conde-Agudelo, A. and R. Romero (2009). “Amniotic fluid embolism: an evidence-based review.” Am J Obstet Gynecol 201(5): 445 e441-413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.052

- Fong A, Chau CT, Pan D, Ogunyemi DA. Amniotic fluid embolism: antepartum, intrapartum and demographic factors. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015 May;28(7):793-8. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.932766. Epub 2014 Jun 30. PMID: 24974876.

- Young BK, Florine Magdelijns P, Chervenak JL, Chan M. Amniotic fluid embolism: a reappraisal. J Perinat Med. 2023 Dec 13;52(2):126-135. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2023-0365. PMID: 38082418.

- Clark, S. L. (2014). “Amniotic fluid embolism.” Obstet Gynecol 123(2 Pt 1): 337-348. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000107

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine . Electronic address, p. s. o., et al. (2016). “Amniotic fluid embolism: diagnosis and management.” Am J Obstet Gynecol 215(2): B16-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ajog.2016.03.012

- Patel, P., et al. (2019). “Markers of Inflammation and Infection in Sepsis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation.” Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 25: 1076029619843338.