Author: Rachel Bridwell, MD (EM Attending Physician; Tacoma, WA) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 25-year-old male is brought to the ED by EMS after sudden onset right testicular pain while playing basketball. He denies any trauma or contact to his scrotum or perineum; however, he endorses severe, sudden pain associated with nausea and non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. He additionally complains of mild lower right abdominal tenderness. Review of systems is otherwise unremarkable.

Vital signs include BP 140/71, HR 119, T 99.2 oral, RR 18, SpO2 98% on room air. On exam he is uncomfortable appearing and has a nontender abdomen. He has a normal penile exam, but the the right hemiscrotum has mild erythema, a horizontal lie, and it is exquisitely tender.

Question: What’s the next step in your evaluation and diagnosis?

Answer: Testicular torsion1-15

Epidemiology

- Bimodal incidence: 1st year of life and teenage years (12-18 years)1,2

- Rare case reports of men age > 40 years with cases of testicular torsion1,2

- 50% of patients with testicular torsion have a previous episode of torsion that spontaneously resolved3

- Testicular pain accounts for 1% of ED visits annually1-4

Anatomy

- Testicular torsion is caused by the twisting of the testis on its blood supply, occluding the vascular pedicle, leading to vascular congestion and testicular ischemia

- Tunica vaginalis is secured to the scrotal wall on the posterolateral side, preventing movement of the testis within the scrotum

- If this attachment occurs too superiorly, known as a bell clapper deformity, it allows for the twisting of the testis

Clinical Presentation:

- Signs and symptoms:

- Symptoms: acute unilateral testicular pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain5

- Signs: absent cremasteric reflex, swelling, testicular tenderness, abnormal testicular position, palpable spermatic cord knot5,6

- 20% of testicular torsion will present with isolated abdominal pain without testicular pain6

- Sensitivity of cremasteric reflex in testicular torsion varies, ranging as low as 60%6,7

- Testicular lie is often difficult to determine, though if an elevated testicle is present, OR=58.86

- Cremasteric reflex is not present in a significant portion of patients at baseline, and it may be present in those with torsion

- Study of n=120, 91% of patients with confirmed torsion had a positive Prehn’s sign and 21% of those diagnosed with epididymitis had a positive Prehn’s sign7

- Ddx: Epididymitis, testicular appendage torsion, varicocele, spermatocele, testicular rupture, appendicitis, nephrolithiasis, ureterolithiasis, AAA, bowel obstruction, mesenteric adenitis

Evaluation:

- Assess ABCs

- +/- low grade fever, late stage may have hypotension and tachycardia due to tissue necrosis, though this is less common8

- Perform a complete physical examination

- Abdomen: Tender in right or left lower quadrant due to referred pain, though abdomen may not be peritoneal

- GU: Erythema, edema, horizontal lie, high riding testis, negative cremasteric reflex is classic7

- Clinical decision tool:

- Testicular Workup for Ischemic and Suspected Torsion (TWIST)9

- Presence of testicular swelling—2 points

- Presence of hard testicle—2 points

- Absence of cremasteric reflect—1 point

- Presence of high riding testicle—1 point

- Presence of nausea/vomiting—1 point

- High risk: 6-7 points, no imaging, suggests immediate urologic detorsion needed

- PPV 100% when >7 pts

- Intermediate risk: 1-5 points, obtain ultrasound, consider ddx

- NPV 96% when < 5 points

- Low risk: 0 points though maintain clinical suspicion with incredibly low threshold to order an ultrasound

- Testicular Workup for Ischemic and Suspected Torsion (TWIST)9

- Imaging:

- Doppler ultrasound10-12

- Sensitivity 88-100% (+LR 8.8-10)

- Specificity 90%

- High resolution US improves sensitivity and specificity to 96 and 99% respectively

- Features on ultrasound:12

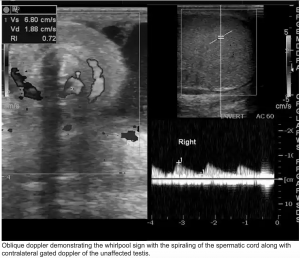

- Decreased doppler flow as compared to contralateral, unaffected testis

- Note: subject to false negatives with arterial but not venous flow or abnormally high-resistance arterial flow12

- Decreased doppler flow as compared to contralateral, unaffected testis

- Increased echogenicity12

- Enlarged hyperemic testicle12

- Whirlpool sign—spiral like pattern of spermatic cord

11

- Whirlpool sign—spiral like pattern of spermatic cord

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): not recommended for urgent testicular pathology as time to detorsion is key

- Sensitivity 93%

- Specificity 100%

- Laboratory evaluation:

- CBC, CMP, UA

- Consider sexually transmitted infection testing

- CBC, CMP, UA

- Doppler ultrasound10-12

Treatment:

- Pain control and IVF rehydration

- Consult urology for detorsion and bilateral orchiopexy13,14

- 40% of patients will have bell clapper deformity on contralateral side13

- Detorsion within 4 hours renders 96% successful salvage15

- Salvage rates decrease to 10% when delayed more than 24 hours15

- If significant delay to detorsion, consider manual detorsion of 540 degrees15

- Medial to lateral detorsion is recommended; however, this is not successful in 1/3 of patients, who may torse in the opposite direction

- Sedation and analgesia are recommended but judicious medication administration to preserve mental status in order to assess for successful detorsion

- Evaluate with US after detorsion attempt

- Patient still requires urology evaluation in the OR and orchiopexy after successful ED detorsion

Pearls:

- Emergent urology consultation for definitive surgical management

- Testicular salvage time ideally as soon as possible though not limited to 6-8 hours, with successful testicular salvage up to 24 hours, especially with intermittent torsion

- Torsion cannot be ruled out by a present cremasteric reflex

- TWIST is a clinical decision tool though clinical gestalt supersedes this tool

You are working in an urban tertiary care hospital when a 16-year-old boy presents to the emergency department after being woken an hour ago with left testicular pain. His left testicle is tender, mildly swollen, and elevated compared to the right. He does not have a cremasteric reflex on the affected side. He is extremely uncomfortable and vomits during the examination. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in this patient’s care?

A) Emergent urology consult

B) Lateral to medial manual detorsion

C) Scrotal ultrasound

D) Urine studies

Answer: A

Testicular torsion can occur in any male patient with a bell clapper deformity, which is present in nearly 1% of the male population. This deformity results from inadequate fixation of the testicle to the tunica vaginalis, allowing for testicle mobility and rotation around the spermatic cord. While testicular torsion is the most common surgical emergency of the testicle, most patients with the bell clapper deformity will not develop torsion. It usually presents with abrupt onset of testicular pain, often waking the patient at night during adolescence, but can present with lower abdominal or inguinal pain. The best predictors for torsion include vomiting, testicular swelling, a firm testicle, a high–riding testicle, and an absent cremasteric reflex. A torsed testicle is only viable for about 4–6 hours after the event. Rapid diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent testicular loss. Immediate consultation with a urologist is necessary for any patient with strong concern for torsion, even before any confirmatory imaging. Imaging can still be obtained while waiting for the urologist to arrive to confirm the diagnosis if needed, as the differential includes epididymitis, orchitis, an incarcerated inguinal hernia, trauma, and torsion of the appendix testis. If surgical consultation is not available or will be delayed, manual detorsion with medial to lateral rotation of the affected testicle should be attempted. Surgical detorsion and orchiopexy should be performed with a contralateral orchiopexy to prevent future occurrences of torsion.

Manual detorsion is appropriate only when emergency operative care is unavailable, as manual attempts may worsen torsion when rotated laterally, which occurs one-third of the time. When manual detorsion is attempted, it should be medial to lateral, not lateral to medial manual detorsion (B). A scrotal ultrasound (C) is the first-line imaging test recommended to rule in or out testicular torsion and should only be performed before surgical consult when patients with testicular pain have reassuring findings on history and exam. Urine studies (D) are helpful to rule out sexually transmitted epididymitis or a urinary tract infection, but these rarely present with testicular pain.

Further Reading

#FOAMed

References

- Mellick LB, Sinex JE, Gibson RW, Mears K. A Systematic Review of Testicle Survival Time After a Torsion Event. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(12):821-825.

- Beni-Israel T, Goldman M, Bar Chaim S, Kozer E. Clinical predictors for testicular torsion as seen in the pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):786-9.

- Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: it is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(1):80-6.

- Perrotti M, Badger W, Prader S, et al. Medical malpractice in urology, 1985 to 2004: 469 consecutive cases closed with indemnity payment. J Urol. 2006;176(5):2154Y2157.

- Mejdoub I, Fourati M, Rekik S, Rebai N, Hadjslimen M, Mhiri MN. Testicular torsion in older men: It must always be considered. Urol Case Rep. 2018; 21:1-2.

- Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, Tanyel FC, et al. Clinical predictors for differential diagnosis of acute scrotum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14(5):333Y338.

- Paul EM, Alvayay C, Palmer LS. How useful is the cremasteric reflex in diagnosing testicular torsion? [Supplement]. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(3):101.

- Sidler D et al. A 25-year review of the acute scrotum in children. S Afr Med J. 1997;87(12) 1696-8.

- Frohlich LC, et al. Prospective Validation of Clinical Score for Males Presenting with an Acute Scrotum. Acad Emerg Med. 2017 Dec;24(12):1474-1482.

- Eaton SH, Cendron MA, Estrada CR, et al. Intermittent testicular torsion: diagnostic features and management outcomes. J Urol 2005;174(4 Pt 2):1532–5.

- Mcdowall J, Adam A, Gerber L, et al. The ultrasonographic “whirlpool sign” in testicular torsion: valuable tool or waste of valuable time? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25(3):281-292.

- Bandarkar AN, Blask AR. Testicular torsion with preserved flow: key sonographic features and value-added approach to diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48(5):735-744.

- Gebreselassie KH, Berhanu E, Akkasa SS, Woldehawariat BY. Torsed spermatocele, a rare cause of acute scrotum: Report of a case and review of literature. Urol Case Rep. 2022;45:102172. Published 2022 Jul 31.

- Barbosa, JA, et al. Development of initial validation of a scoring system to diagnose testicular torsion in children. The Journal of Urology. 2013; 189:1853-8

- van Welie M, Qu LG, Adam A, Lawrentschuk N, Laher AE. Recurrent testicular torsion post orchidopexy – an occult emergency: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92(9):2043-2052.