Authors: Luke Wohlford, MD (EM Resident Physician, University of Vermont Medical Center) and Joseph Kennedy, MD (EM Attending Physician, University of Vermont Medical Center) // Reviewed by: Summer Chavez, DO, MPH, MPM (EM Attending Physician, University of Houston); Marina Boushra (EM-CCM Attending Physician, Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 35-year-old female with no significant past medical history is brought to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services (EMS) from the scene of an apartment fire, where she jumped six stories out of a window to the pavement below. Her initial vital signs are blood pressure 76/54 mmHg, heart rate 128 bpm, temperature 37.0˚ C, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air. The presenting fingerstick glucose is 108 mg/dL. Her airway is intact, and she has equal bilateral breath sounds. Pulses in all four extremities are weak but intact and symmetric. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is 14 (3E-5V-6M), and she arrives in a cervical collar placed pre-hospital. A focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) exam is negative, and her secondary survey is notable for a pelvis that is significantly tender to gentle anterior and lateral compression.

How should pelvic fractures be identified in unstable trauma patients?

What is the EM physician’s role in the stabilization of unstable pelvic injuries?

Introduction

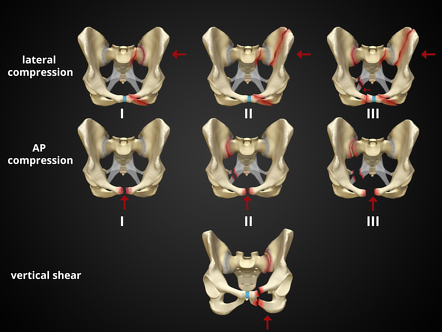

The pelvic ring is made up of the bony ilium, ischium, pubis, and sacrum, which are held together with ligaments. Pelvic fractures can involve disruptions in any of the bony or ligamentous structures of the pelvic ring. Due to the round shape of the pelvic ring, multiple fractures typically occur concurrently. Conceptually, pelvic ring fractures are similar to breaking a hard pretzel. The structures of the ring uniformly experience shearing forces that lead to fractures in at least two discrete locations. While single-bone fractures can occur, they are far less common. Multiple classification systems have been devised to succinctly describe pelvic ring fractures. The Young-Burgess classification is the most common among these. It is generally divided into categories by the suspect traumatic mechanism, including anterior-posterior (AP), lateral compression (LC), and vertical shear fracture.1 These categories of fractures can be visualized in Figure 1. The AP and LC fractures are further categorized into grades I-III, with grades II and III of each type being mechanically unstable.2 Vertical shear fractures are also unstable. For a broader overview of pelvic trauma, please review Dr. Lupez’s 2017 article here: http://www.emdocs.net/pelvic-fractures-ed-presentations-management/.

Figure 1: The Young-Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures (source: https://radiopaedia.org/cases/37824/studies/39745?lang=us)3

It is paramount to differentiate the definitions of “hemodynamically unstable” and “mechanically unstable” pelvic fractures. The nuances of fracture patterns and delineating mechanically unstable pelvic fractures from stable ones is less important to the ED. In fact, the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) classification assigns grades I-III depending on their Young-Burgess classification, but any patient hemodynamically unstable from their pelvic fracture is automatically WSES grade IV regardless of their fracture pattern.4 Patients with pelvic fractures are considered unstable when systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg and heart rate >120bpm, or in those with dyspnea, altered mental status, or skin findings of shock.4 This is the framework the ED resuscitationist should be operating under, as hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma patients require a different approach compared to stable patients who will undergo CT, routine pelvic fixation, and definitive surgical repair. Patients with unstable pelvic fractures have high morbidity and mortality. In one series, patients with unstable pelvic fractures had an overall mortality rate of 36%.5

Initial Evaluation

The key to the initial resuscitation of the unstable pelvic trauma patient is to rapidly identify and treat the most life-threatening pathology. Pelvic ring fractures in adults with healthy bones require high-energy forces, typically motor-vehicle accidents, pedestrian injuries, crush injuries, and falls from height.6 The clinician must consider traumatic involvement of additional systems, as an estimated 50% of pelvic fractures have concurrent injuries.6 A primary survey on a trauma patient should reveal deficiencies in airway, breathing, and circulation, which should be rapidly corrected. Identifying and treating the hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma patient is the focus of the remainder of this article.

If a pelvic binder was placed by EMS, inquire whether this was placed empirically or if mechanical pelvic instability was already elicited. There likely is little benefit to testing pelvic stability with the binder in place even if it was placed empirically, as the binder should not be cleared prior to a pelvic x-ray. Pelvic fractures may not be obvious, especially in the obtunded patient. External clues are not often present, with one study finding only 7.6% of pelvic fractures to be open.7 Sensitivity for finding a pelvic ring fracture by physical examination approaches 90% but is decreased in patients with GCS < 13.8

If a pelvic binder was not already placed, gentle anterior compression at the anterior superior iliac spine and lateral compression of the iliac crests can be performed. Pain, movement, or crepitus with these maneuvers are highly concerning for pelvic fractures. Assessment of pelvic stability with lateral and anterior compression should be done a maximum of one time so as to not exacerbate damage from the injury. Limb-length discrepancy is not often apparent in pelvic fractures and would be more suggestive of a femoral fracture or dislocation. Examples of radiographs indicative of pelvic fractures that EM physicians should be familiar with are below in Figures 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 2: Open book pelvic fracture. Note the significant diastasis of the pubic symphysis. Case courtesy of Leonardo Lustoasa and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/open-book-pelvic-fracture-4 9

Figure 3: Vertical shear pelvic fracture. Note the widening of the right sacroiliac joint and the pubic symphysis with superior displacement of the right hemipelvis. Case courtesy of Stefan Tigges and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/vertical-shear-injury 10

Figure 4: Lateral compression fracture. Note fractures to the left hemipelvis, including fractures of the left superior and inferior pubic rami and left posterior ilium with impaction of the left sacrum. Case courtesy of Stefan Tigges and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/lateral-compression-2-pelvic-fracture11

There is a high rate of concomitant injuries in the pelvis related to these fractures, including bladder rupture, ureteral injury or transection, bowel perforation, rectal injury, and sacral nerve injuries.12 Patients with pelvic fractures and concerning straddle mechanisms should be thoroughly evaluated for genitourinary injuries. This is less critical in ED management of the unstable pelvic fracture, as the optimal site for identification of rectal or vaginal tears is the operating room.

Resuscitation

The pelvic cavity can contain 4 to 6 liters of blood, so even in an isolated pelvic trauma, multiple units of blood products may be required to achieve hemodynamic stability.13 Massive transfusion protocols (MTP) are hallmarks of trauma resuscitation, and they are critical to the unstable pelvic fracture patient. Institutional protocols should be utilized, keeping in mind that either whole blood or a 1:1:1 ratio of packed red blood cells, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma are optimal.14 Given the risk/benefit profile, in the critical and most unstable of pelvic trauma patients tranexamic acid (TXA) 1 g should be considered as adjunctive therapy, followed by infusion, within 3 hours of the injury. Another option is to administer 2 g of TXA without infusion. Data from the CRASH-2 trial suggest that the mortality benefit of TXA exists until 3 hours post-injury and diminishes for every 15-minute delay.15

If the cause of bleeding is not apparent externally, special attention should be paid to the pelvis, femur, and FAST exam to investigate the areas patients can bleed internally. Unstable patients with positive FAST exams will often go to the operating room expediently depending on the entire clinical picture, so further workup and treatment of pelvic fractures in these scenarios will occur outside of the ED with surgical fixation.

Early administration of antibiotics may not be prioritized in the setting of hemodynamic instability but antibiotics are a critical portion of management if open fracture is suspected.12 An AP x-ray of the pelvis should be obtained in the ED for unstable patients.16 A generally accepted rule of the management of traumatic injuries is that hemodynamically unstable traumas should not go to the CT scanner.4,17 This is not necessarily true in modern centers with a CT within close vicinity of the resuscitation bay, though the team must manage any immediately life-threatening injuries and stabilize as best as possible prior to CT. CT plays an important role, as it can assist in determining optimal therapy, but when moving the patient to the CT, the managing team must be prepared for any patient decompensation and ensure appropriate blood products are available and other interventions can be completed as quickly as possible during CT. Obtaining a CTA could identify which pelvic fractures are among the 15% who have arterial bleeding and therefore would provide insight into who may benefit from angioembolization. This imaging can only be obtained when hemodynamics feasibly allow CT imaging and is often ordered by trauma teams after an initial fixation or packing has been performed in patients continuing to hemorrhage. Contrast extravasation or blush near an artery, or a hyper-attenuated hematoma near a vessel is suggestive of arterial injury.18

Pelvic Binding

As soon as a hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture is identified, a binder should be placed. Decreasing the size of the pelvic cavity and reapproximating the pelvic bones can provide some bleeding control, even if this is not definitive treatment. Blood loss from pelvic fractures is venous in an estimated 85% of cases, making compression a viable method of bleeding control in most cases.19,20 Binding in the ED is accomplished either with a commercial binder or a simple sheet. Figure 2 provides an example of a sheet secured with zip-ties, and hemostats can also be used to secure the sheet. In a pinch, a knot can be tied with the sheet, but this is suboptimal and more likely to cause pressure injuries. The binder should be centered on the greater trochanters to most safely and effectively direct compression.

There is some controversy about which pelvic fractures are amenable to binding, with some texts recommending against their use in lateral compression or vertical shear fractures. Recent literature supports the empiric use of pelvic binders in all types of pelvic fractures while working towards definitive management.21,22 There is evidence that the use of a pelvic binder in any unstable trauma could improve mortality, even without physical or radiographic evidence of pelvic fracture.23 Pelvic binding remains a critical resuscitation step well within the purview of the ED physician, and can be reviewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWLBZKeWEkg&ab_channel=CoreEM.

Figure 5: Pelvic binding with a sheet. Note placement over the greater trochanters. 24

Next Steps in Management

The Western Trauma Association (WTA) recommends moving to one of three potential treatments for unstable pelvic fractures with a negative FAST: surgical fixation, resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA), or preperitoneal packing (PPP).17 The current literature on this topic is equivocal on which initial step is best, and the optimal approach likely depends on multiple patient factors. This is a unique scenario where interventional radiology, orthopedic surgery, and trauma surgery all have potential roles, and it is most important for emergency physicians to know their own institutional policies on unstable pelvic trauma.

Surgical Fixation

The definitive treatment of pelvic fractures is surgical fixation, either traditionally with external fixation or with novel internal fixation.25,26 The specifics of these procedures are not relevant to the ED physician, but, regardless of method, an orthopedic surgeon or trauma surgeon trained in pelvic stabilization will be required. Certain hemodynamically unstable patients will proceed directly to surgical fixation, and this decision is generally a function of the surgical abilities of the facility. The emergency physician must be intimately familiar with the resources within their own geographic region to determine whether local stabilization or transfer is most appropriate.

Preperitoneal Packing

While most often done in the operating room, PPP may be done in the trauma bay in rare instances depending on the institution. The procedure is performed with an incision superior to the pubis, with laparotomy pads placed around the bladder to provide pelvic and retroperitoneal tamponade.27 This is the first-line treatment recommended by the WSES for unstable pelvic fractures and has data suggestive of improved mortality compared to REBOA and even angioembolization.28,29 Regional differences have developed so that PPP is more often first-line in European centers.30 Patients with PPP often go on to receive angioembolization if they are persistently hypotensive prior to surgical fixation. A general surgeon can facilitate PPP while awaiting transfer to a trauma center for definitive management.

REBOA

Recent guidelines in pelvic trauma have incorporated REBOA as a potential bridge to definitive therapy.4,16,17 The concept is analogous to aortic cross-clamping but allows for the selection of occlusion site to minimize organ ischemia. This procedure is performed by accessing the femoral artery and advancing a balloon that can be inflated in the desired aortic region. For isolated pelvic trauma, zone III (infrarenal) is the ideal occlusion location. However, the balloon may need to be placed higher for concurrent intraperitoneal injuries. REBOA may be the pelvic fracture stabilization procedure most accessible to ED physicians but much more data will be required before it becomes a standard of care. The largest REBOA study to date demonstrated a serious complication rate of 11%, and its population had a mortality rate of 54%.31 This high mortality rate may have been due to sicker patients receiving REBOA, but still does not provide convincing efficacy of this procedure. Additional studies have suggested increased morbidity of REBOA with concurrent TXA use,32 increased mortality when used prior to angioembolization,30 and higher mortality rates when compared to PPP.28

Angioembolization

Angioembolization is performed in an estimated 55% of unstable pelvic trauma patients in the United States and is performed more frequently than PPP (47%).6 Especially for the 15% of unstable pelvic fracture patients who have arterial bleeding, angioembolization performed in the interventional radiology (IR) suite or operating room will provide critical source control.4 Angiography with embolization is often initiated in patients who remain persistently hypotensive after MTP and damage control surgery and does not always require CT scanning for planning in these cases.19 Despite its dominance in the US, angioembolization is not first-line in the unstable pelvic fracture patient in either the WSES or WTA guidelines and is relegated to adjunctive therapy for patients who first receive fixation or PPP. One systematic review found 33% mortality with angioembolization monotherapy and 23% for PPP, but the baseline characteristics were different between the groups.34 This and another study each found that approximately a quarter of patients who initially received PPP went on to receive angioembolization, more consistent with current guidelines.35,36

Disposition

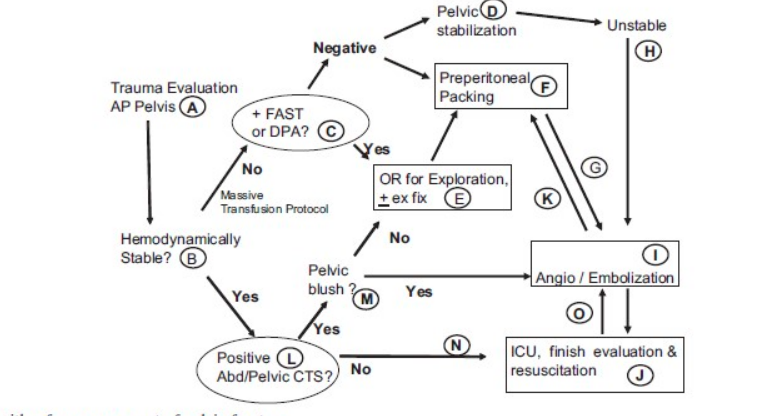

Unstable pelvic fractures should ideally be admitted to dedicated trauma centers. If the initial ED they present to does not have the capacity to perform angioembolization or external fixation, the patient should be transferred if possible once stabilized. Low resource centers should maintain their own protocol that fits their facility’s capabilities and likely will emphasize pelvic binding, MTP, and CT angiography imaging prior to transfer if feasible. 36 An example of a pathway for pelvic fracture patients from the Western Trauma Association summarizes the above discussions in Figure 6.

Figure 6: An example of an algorithm for the management of pelvic fractures with hemodynamic instability, as recommended by the Western Trauma Association.

Case Resolution

The call for MTP was quickly made, and a sheet was used as a pelvic binder as soon as pelvic instability was elicited. An x-ray in the trauma bay demonstrated an AP grade III fracture. Interventional radiology and orthopedic surgery were emergently consulted, and the patient was transferred to the operating room, where she had external fixation followed by angiography, which did not demonstrate an arterial bleed. She recovered in the SICU and was discharged two weeks later.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures have high mortality rates and there is equipoise within trauma literature on optimal definitive treatment.

- Prioritize volume resuscitation and coordination with IR, trauma surgery, and orthopedic surgery to determine the next steps and potential advanced imaging. Advocate for emergent surgical interventions in the unstable patient that cannot tolerate CT imaging.

- Institutional protocols vary, but unstable pelvic trauma patients will likely need a combination of preperitoneal packing, surgical fixation, angioembolization, and REBOA. Transfer should be initiated rapidly if the patient’s needs are greater than the available resources.

References

- Barton MA, Derstine HS, Barclay-Buchanan CJ. Pelvis Injuries. In:Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yearly DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds.Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e. McGraw Hill; 2016.

- Glick Y, Knipe H, Hacking C, et al. Young and Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-56868. Published November 8, 2022. Accessed on April 15, 2023.

- Skalski M, Pelvic fracture diagrams. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-37824 Published June 23, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Coccolini F, Stahel PF, Montori G, et al. Pelvic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines.World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:5. Published 2017 Jan 18. doi:10.1186/s13017-017-0117-6

- Anand T, El-Qawaqzeh K, Nelson A, et al. Association Between Hemorrhage Control Interventions and Mortality in US Trauma Patients With Hemodynamically Unstable Pelvic Fractures. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(1):63-71. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.5772

- Perumal R, S DCR, P SS, Jayaramaraju D, Sen RK, Trikha V. Management of pelvic injuries in hemodynamically unstable polytrauma patients – Challenges and current updates [published correction appears in J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021 Aug 05;21:101558]. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;12(1):101-112. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2020.09.035

- Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. Demographic epidemiology of unstable pelvic fracture in the United States from 2000 to 2009: trends and in-hospital mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):380-385. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab0cde

- Bakhshayesh P, Boutefnouchet T, Tötterman A. Effectiveness of non invasive external pelvic compression: a systematic review of the literature. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:73. Published 2016 May 18. doi:10.1186/s13049-016-0259-7

- Lustosa L, Open book pelvic fracture. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-99312. Published April 22, 2022. Accessed April 29, 2023.

- Tigges S. Vertical shear injury. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-166885. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2023.

- Tigges S. Lateral compression 2 pelvic fracture. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-166888. Published April 18, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2023.

- Mi M, Kanakaris NK, Wu X, Giannoudis PV. Management and outcomes of open pelvic fractures: An update. Injury. 2021;52(10):2738-2745. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2020.02.096

- Steven J. Morgan MD. Pelvic fractures. Abernathy’s Surgical Secrets (Sixth Edition). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323057110000288. Published November 11, 2009. Accessed April 16, 2023.

- Copp J, Eastman JG. Novel resuscitation strategies in patients with a pelvic fracture. Injury. 2021;52(10):2697-2701. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2020.01.042

- CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):23-32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-16. Incagnoli P, Puidupin A, Ausset S, et al. Early management of severe pelvic injury (first 24 hours) [published correction appears in Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019 Dec;38(6):695-696]. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38(2):199-207. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2018.12.003

- Tran TL, Brasel KJ, Karmy-Jones R, et al. Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Management of pelvic fracture with hemodynamic instability-2016 updates. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(6):1171-1174. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001230

- Raniga SB, Mittal AK, Bernstein M, Skalski MR, Al-Hadidi AM. Multidetector CT in Vascular Injuries Resulting from Pelvic Fractures: A Primer for Diagnostic Radiologists. Radiographics. 2019;39(7):2111-2129. doi:10.1148/rg.2019190062

- Vaidya R, Waldron J, Scott A, Nasr K. Angiography and Embolization in the Management of Bleeding Pelvic Fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(4):e68-e76. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00600

- Cothren CC, Osborn PM, Moore EE, Morgan SJ, Johnson JL, Smith WR. Preperitonal pelvic packing for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures: a paradigm shift. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):834-842. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31803c7632

- Bakhshayesh P, Boutefnouchet T, Tötterman A. Effectiveness of non invasive external pelvic compression: a systematic review of the literature. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:73. Published 2016 May 18. doi:10.1186/s13049-016-0259-7

- Blum L, Hake ME, Charles R, et al. Vertical shear pelvic injury: evaluation, management, and fixation strategies. Int Orthop. 2018;42(11):2663-2674. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-3883-1

- Hsu SD, Chen CJ, Chou YC, Wang SH, Chan DC. Effect of Early Pelvic Binder Use in the Emergency Management of Suspected Pelvic Trauma: A Retrospective Cohort Study [published correction appears in Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 30;19(11):]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10):1217. Published 2017 Oct 12. doi:10.3390/ijerph14101217

- Heilman, J. File:PelvicBinding.webm [Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PelvicBinding.webm. Published October 9, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2023.

- Ohmori T, Kitamura T, Nishida T, Matsumoto T, Tokioka T. The impact of external fixation on mortality in patients with an unstable pelvic ring fracture: a propensity-matched cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(2):233-241. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.100B2.BJJ-2017-0852.R1

- Kumbhare C, Meena S, Kamboj K, Trikha V. Use of INFIX for managing unstable anterior pelvic ring injuries: A systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(6):970-975. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2020.06.039

- Nickson, C. Pre-peritoneal packing. Life in the Fastlane. https://litfl.com/pre-peritoneal-packing/. Published June 6, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2023.

- Mikdad S, van Erp IAM, Moheb ME, et al. Pre-peritoneal pelvic packing for early hemorrhage control reduces mortality compared to resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in severe blunt pelvic trauma patients: A nationwide analysis. Injury. 2020;51(8):1834-1839. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2020.06.003

- Parry JA, Smith WR, Moore EE, Burlew CCC, Mauffrey C. The past, present, and future management of hemodynamic instability in patients with unstable pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 2021;52(10):2693-2696. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2020.02.101

- Li P, Liu F, Li Q, Zhou D, Dong J, Wang D. Role of pelvic packing in the first attention given to hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture patients: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2022;23(1):29. Published 2022 Jul 7. doi:10.1186/s10195-022-00647-6

- Coccolini F, Ceresoli M, McGreevy DT, et al. Aortic balloon occlusion (REBOA) in pelvic ring injuries: preliminary results of the ABO Trauma Registry. Updates Surg. 2020;72(2):527-536. doi:10.1007/s13304-020-00735-4

- Laverty RB, Treffalls RN, McEntire SE, et al. Life over limb: Arterial access-related limb ischemic complications in 48-hour REBOA survivors. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;92(4):723-728. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003440

- Benders KEM, Leenen LPH. Management of Hemodynamically Unstable Pelvic Ring Fractures. Front Surg. 2020;7:601321. Published 2020 Dec 4. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2020.601321

- McDonogh JM, Lewis DP, Tarrant SM, Balogh ZJ. Preperitoneal packing versus angioembolization for the initial management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;92(5):931-939. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003528

- Lin SS, Zhou SG, He LS, Zhang ZX, Zhang XM. The effect of preperitoneal pelvic packing for hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic fractures. Chin J Traumatol. 2021;24(2):100-103. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.01.008

- Mejia D, Parra MW, Ordoñez CA, et al. Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture: A damage control surgical algorithm that fits your reality. Colomb Med (Cali). 2020;51(4):e4214510. Published 2020 Dec 30. doi:10.25100/cm.v51i4.4510