EM@3AM: Periorbital Cellulitis

- Jun 17th, 2023

- Jackie Nguyen

- categories:

Author: Jackie Nguyen, MD (EM Resident Physician, UTSW – Dallas, TX); Joshua Kern, MD (Assistant Professor of EM/Attending Physician, UTSW – Dallas, TX) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

An 8-year-old boy with no medical history born full term presents with left eyelid swelling for 2 days. Parents report the swelling has progressively worsened and is greater in the upper eyelid. It is associated with erythema, warmth, and tenderness. They also note subjective fevers. For the past week, the patient had watery rhinorrhea, dry cough, and nasal congestion. Parents deny recent trauma or known insect bite. The patient’s vitals include T 100.2F, BP 113/67, HR 123, RR 26, SpO2 of 99% on room air. On physical exam, the patient is non-toxic appearing. His eye exam is significant for edema and erythema to the left periorbital region greater in the upper eyelid. There is mild warmth but no crusting or active drainage. His extraocular movements are intact and painless, and there is no conjunctivitis or chemosis.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Periorbital cellulitis

Definition1, 2

- Infection of the skin, soft tissue, and surrounding structures anterior to the orbital septum including the upper and lower eyelids

- Also known as preseptal cellulitis

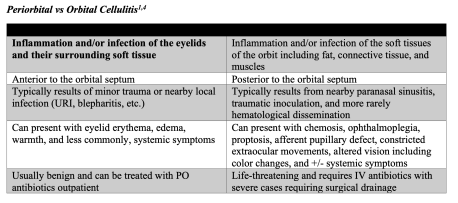

- Often confused with orbital cellulitis which is a serious infection posterior to the orbital septum within the orbit that requires parenteral antibiotics and sometimes emergent surgical intervention

Epidemiology2, 3

- Can occur in individuals of all ages, but more commonly occurs in children under the age of 10

- Several etiologies have been linked to the development of periorbital cellulitis which include:

- Bacterial

- This is the most common cause with the most frequently isolated bacteria being Staphylococcus aureus and the Streptococcus species

- Less commonly linked to Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Proteus, Neisseria, Nocardia, Pasteurella, Mycobacterium, and Bacillus

- This is the most common cause with the most frequently isolated bacteria being Staphylococcus aureus and the Streptococcus species

- Viral

- Less common cause

- Adenovirus, herpes simplex, and varicella zoster have been implicated as causes of periorbital cellulitis

- Fungal

- Very rare and more often seen in immunocompromised individuals

- Reported cases with Aspergillus and Mucor

- Bacterial

Pathophysiology2

- Typically results as a complication of progressing rhinosinusitis but can also occur secondary to oral, upper respiratory, auricular, lacrimal, and other facial infections

- Associated with Haemophilus influenza type b in unvaccinated children and more universally, Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Orbits are bordered by the paranasal sinuses and lined with periosteum

- Ethmoiditis is the most common rhinosinusitis leading to periorbital cellulitis as the lamina papyracea separating the ethmoid sinus and orbits are very thin and permeable facilitating easy spread of infection

- The lamina papyracea is made of Zuckerkandl’s dehiscence which are small fenestrations allowing neurovascular structures to pass through as well as microbial organisms leading to infection

- Can also arise after trauma to the area as a skin defect can be a nidus for infection

- Associated with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Other causes include hematogenous seeding and expansion of pre-existing impetigo

Clinical Presentation1, 2, 4

- Patients often times, but not always presents with a history of recent trauma (e.g., insect bite, scratch, etc.) or nearby infection (e.g., URI, dacryocystitis, blepharitis, impetigo, hordeolum, etc.)

- Characterized by edema, erythema, warmth, and tenderness of the eyelid and surrounding tissue

- Symptoms and signs are usually unilateral

- Can be rapidly progressive

- Can have difficulty opening eyelids secondary to the degree of eyelid edema

- Erythema and edema will often expand beyond the arcus marginalis (region where orbital septum attaches into the periosteum)

- In orbital cellulitis, the erythema and edema can abruptly stop at this landmark

- Can have systemic symptoms such as fever and generalized malaise although not always present

- Usually, the patient will not have pain or limitations of extraocular eye movement, visual changes, chemosis, proptosis, globe displacement, or pupillary defects

- If these symptoms are present, it is likely the patient has orbital cellulitis, but in severe cases of periorbital cellulitis there can be limitations with extraocular movements secondary to eyelid edema

- Intraocular pressures are normal in periorbital cellulitis

Diagnosis1, 4, 5

- This is a clinical diagnosis made through history and physical exam

- Does not typically require ophthalmology consultation

- Physical examination will demonstrate mild to marked eyelid erythema and edema, but normal intraocular pressures, visual acuity, and globe motility

- If the exam/history is equivocal or limited secondary to age (i.e., pediatric population), an orbital and/or sinus CT scan with IV contrast can be performed to assist with diagnosis

- Will demonstrate eyelid edema, but should not show proptosis or orbital fat streaking which suggest post orbital septal involvement and orbital cellulitis

- Can also be obtained if suspicious for periorbital infection complications, those with marked symptoms (e.g., swelling, chemosis, fever, etc.), no improvement after 24-48 hours after initiating antibiotics

Complications1

- Periorbital cellulitis rarely leads to the development of serious complications, but infections can propagate through the venous system of the face

- This system is valveless allowing for facile and rapid dissemination of infection to the orbits, cavernous sinuses, and eventually the intracranial structures

- Can spread and develop into orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, subperiosteal abscess, and orbital abscess

- Very rarely necrotizing fasciitis can develop when the infection is secondary to β-hemolytic Streptococcus

- Presents with rapidly progressive symptoms with impressive violaceous skin changes

Treatment1-3

- Mainstay of treatment is antibiotics with S. aureus, Streptococcal, and anaerobic coverage

- Often can treat with oral antibiotics for 5-7 days, but if symptoms are severe, the patient has significant co-morbidities and/or is immunocompromised, or occurs in children less than two-years-old, hospital admission for parenteral antibiotics should be considered

- For outpatient empiric MRSA coverage, one of the following antibiotics should be given:

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 160mg/800mg to 320mg/1600mg BID

- Clindamycin 300mg every eight hours

- Doxycycline 100mg BID

- Not recommended in children under 8 years

- In combination with one of the following to cover group A strep:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate 875mg BID

- Cefpodoxime 400mg BID

- Cefdinir 300mg BID

- For children, follow weight-based dosing for appropriate coverage

- For inpatient treatment, the following regimen is typically used:

- Vancomycin 25-35mg/kg IV as a loading dose then 15-20mg/kg IV two to three times daily in combination with one of the following:

- Ampicillin-sulbactam 3g IV QID

- Ceftriaxone 2g IV QD

- Levofloxacin 750mg IV QD

- Cefotaxime 2g IV every four hours

- Vancomycin 25-35mg/kg IV as a loading dose then 15-20mg/kg IV two to three times daily in combination with one of the following:

Prognosis2

- Majority of cases will resolve with treatment

- If not improving, consider changing antibiotics or evaluating for orbital cellulitis and other differentials

Pearls

- Periorbital cellulitis is a generally benign condition that involves infection of the eyelids and surrounding tissue without orbital involvement

- Majority of cases are a result of bacterial infection secondary to rhinosinusitis, but can result from trauma or other nearby infections

- It is clinically diagnosed but careful physical examination should be performed to distinguish it from orbital cellulitiswhich is an ophthalmic emergency

- Treatment for most individuals includes oral antibiotics that cover staph, strep, and anaerobes, but parenteral antibiotics should be considered for those with significant co-morbidities or young children

- Complications are rare

A 42-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and diabetes presents to the emergency department with redness, swelling, and mild pain around her left eye for 2 days. She reports no vision changes or fever. She remembers rubbing and scratching around her eye a few days ago but does not recall any trauma. On exam, she has erythema with edema of the lateral upper eyelid and under her left eye. Her conjunctivae are clear, and no foreign bodies are found. Extraocular movements are intact, and her vision is 20/30 in both eyes. What is the most appropriate pharmacological treatment for this illness?

A) Oral cefdinir

B) Oral clindamycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate

C) Topical ciprofloxacin drops

D) Topical erythromycin ointment

Answer: B

This patient is presenting with signs of preseptal cellulitis, an infection of the anterior portion of the eyelid that does not involve the orbit or other orbital structures. It is generally a mild condition that has few complications when treated appropriately. Symptoms can be similar to orbital cellulitis, a more severe infection involving the orbit. However, in contrast to orbital cellulitis, preseptal cellulitis does not present with ophthalmoplegia, pain with eye movements, and proptosis. Preseptal cellulitis generally arises from external bacterial sources, with the most common etiologies beingStreptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and other streptococcal species. Blood cultures are rarely positive, and site cultures are difficult to obtain. Treatment is done empirically and should cover sinus and skin flora. However, the choice of treatment has been made more difficult with the emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Empiric antibiotic therapy that has good coverage for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coverage for streptococcal species is clindamycin with amoxicillin-clavulanate. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can substitute for clindamycin. Most patients can be treated with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.

Oral cefdinir (A) was previously a good treatment option for preseptal cellulitis. However, it does not have activity against community-acquired MRSA. It is no longer recommended as initial therapy unless also treating with an antibiotic that provides coverage for MRSA. Topical ciprofloxacin drops (C) would be recommended therapy for a patient with bacterial conjunctivitis or corneal abrasion with risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. This patient has signs and symptoms of preseptal cellulitis, not conjunctivitis. Topical erythromycin ointment (D) is therapy for mild bacterial conjunctivitis. As already mentioned, this patient has signs and symptoms of preseptal cellulitis, not conjunctivitis.