Damage Control Resuscitation at the Non-Trauma Center – Part 1: Personal and Team Preparation

- Sep 13th, 2017

- Scott McAninch

- categories:

Scott McAninch, MD, FACEP (@MacAttackSM, EM Attending Physician, Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital and McLane Children’s Hospital) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case 1

You are working your first shift in a small 8-bed Emergency Department (ED), which is not a designated trauma center. You just evaluated a 2-year-old with non-stop crying, an 80-year-old with chest pain, and a 22-year-old with vaginal discharge. Suddenly, you hear tires squeal outside the ED entrance from a fleeing vehicle, out which falls onto the parking lot your next patient. He is immediately carried back to your ED’s only open room for evaluation. Your initial visual exam reveals an adolescent-aged male, who appears pale, has decreased responsiveness, and has fresh blood on his jacket, shirt, and pants. Two nurses rush into the patient room and say “we don’t see trauma very often here…” Your resuscitation starts…

Introduction

Trauma patients with significant injuries may arrive at the non-trauma designated hospital by various means: they may check-in through triage, be “dropped off” unexpectedly (in the parking lot), or arrive under the care of pre-hospital providers. Trauma patients with significant injuries and illness have better outcomes if transferred to a designated trauma center (1-5). Trauma center transfer guidelines exist to help identify such patients (6). Additionally, in pediatric patients, a Revised Trauma Score of < 12 or a Pediatric Trauma Score of < 8 are indications for transfer to a pediatric trauma center (7). If you are working in a non-trauma center, and your trauma patient appears “sick” at any point in care (even if on primary survey), meets any aforementioned criteria for transfer to a trauma center, or may require resources beyond you or your facility, then your priorities are to provide life-stabilizing care and then transfer to the nearest accepting trauma center as soon as possible. In the first of this two-part series, we will discuss personal mental preparation and creating a calm and safe resuscitation environment for the “sick” trauma patient in the non-trauma center. The second part of the series will discuss the clinical aspects of a focused trauma resuscitation in the non-trauma center and process improvement.

Prepare yourself

Establishing mental calm and common stress responses

The initial resuscitation scene may be chaotic and shrouded in uncertainty. Additionally, you may have just woken up from a nap or be winded from running to the ED. As the resuscitation leader, you need to establish within your own mind a sense of tranquility and confidence in knowing you have a goal-directed pathway by which to guide the resuscitation, namely ABCDE… You need to mentally “slow down” the developing patient care scene in front of you (in a “Matrix” kind-of-way), providing a calm awareness of all moving pieces in the room: from the injured patient, to ED personnel and their actions, to the needed equipment / medications / resources that are or are not in the patient room, and thinking ahead in next patient care steps. Recognize the “fight or flight” responses of tachycardia, tachypnea, and muscle fasciculations are normal responses to a stressful environment, even for some veteran resuscitationists (8). Embrace them as helpful adaptations and control them to maximize your orchestration of the resuscitation. EMCRIT Podcast 118 provides an excellent summary of acclimating to stress responses in the resuscitation scene (9). Importantly, the “fight or flight” response may predispose you to enhanced GI and urinary activity in the middle of a resuscitation. So, if you have time before patient arrival, use the bathroom before patient arrival (the “battle crap”).

Your verbal and non-verbal communication

Be aware that your verbal and non-verbal communication will (re)set the team’s “resiliency thermostat” in the resuscitation room. Your leadership goal is to create and maintain a calm, orderly, relatively quiet environment that is goal-oriented to complete essential resuscitation tasks. Speak slowly, using a calm tone of voice at the lowest feasible volume. Maintain respect and dignity among all team members. Rudeness has negative consequences on medical team performance (10). If an error occurs, redirect staff in a calm, congenial manner. Take opportunities to praise your team members. Patients and family members should sense collegiality between you and your team. Your non-verbal communication will either promote a sense of calm or frustration and uncertainty. Even if wearing a face mask, forcefully wrinkled eyes and forehead may convey negativity. Avoid cavalier and hostile movements, such as “grabbing” equipment in an aggressive, TV drama-like manner. Be deliberately calm, meticulously purposeful, and “slow” with your procedural technique (even if your hands are shaking). As it has been said, “slow is smooth, and smooth is fast”.

Cognitive awareness of your ED resources

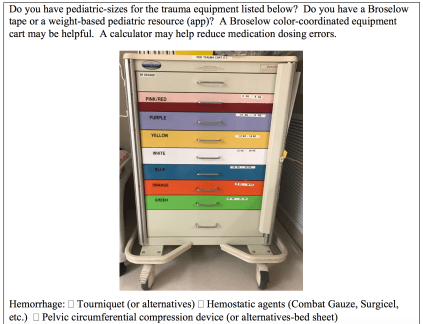

You need to know which trauma resuscitation resources are available in each ED at which you work. Mobilize the (appropriate-sized or weight-based) equipment, medications, and blood products early as you anticipate the need. Below is a sample of resources you might utilize for damage control resuscitation (NOT an exhaustive list):

Equipment

Prepare your team to establish and maintain a calm and safe resuscitation environment

Ensure the environment is safe

Does the patient need decontamination (organophosphates, flammable substances)? How do you decontaminate in your ED (with a hose in the parking lot, ED shower)? Further, ensure there are no weapons (check footwear, too) or sharp objects, such as broken pipes or uncapped needles. If there is a penetrating foreign body that should not be removed, then stabilize it. Dawn the appropriate protective gear (gowns, masks with face shields, shoe covers). A mobile cart consolidated with all needed protective gear is helpful. Ensure team movement is safe: guard against slippery floors and tubes/lines that are tripping hazards. Verbal orders are often used. Ask the nurse to repeat back the medication, dose and route to ensure it is correct. Write down doses for all to see, when possible. Use a calculator, if possible.

Identify your resuscitation team

How many nurses and technicians are present? Do you have a respiratory therapist (RT) (you may be securing the ET tube and setting up the ventilator)? Do you need to request more nurses from inpatient floors, OR, and/or ICU? Transport team personnel who arrive later are usually a welcomed addition to the team. On the other hand, you may have too many “helpers” in the resuscitation room. Ask your charge nurse to help redistribute staff to meet your trauma resuscitation needs while concurrently ensuring care of other ED patients.

Encourage mental calm among your team

The stress of an undifferentiated “sick” trauma patient may prompt team members to operate in a “flight or fight” mode, too. Try to instill within them a sense of comfort with the reality of temporary clinical uncertainty and reassure them verbally by providing calm, yet confident, specific task assignments and next steps/goals in resuscitation care. The situation is analogous to starting to read chapter one of a novel with many chapters. We don’t know the entire story yet, but be confident the plot will unfold and become clearer as we read more, and we will adapt with resiliency to the developing situation in a prioritized (primary survey) manner.

Leading the team

Calmly ensure each team member clearly understands their individual task(s), where in the room they should stand (at least initially), and upcoming individual and team goals in immediate care. Create an environment where patient care questions are welcomed. Also, be aware of the skill sets of team members. Some ED technicians may be able to start IV’s, allowing nurses to focus on other tasks.

If you have time to prepare before patient arrival

After receiving notification of the incoming patient, gather your “team” and discuss anticipated care steps, what weight/size-appropriate equipment needs to be mobilized, and time to arrival. Ask the team to repeat back instructions, if needed. Write down weight-based doses of anticipated medications. Encourage questions, and invite the team to focus on maintaining calm throughout the resuscitation. Summon the x-ray tech, ask the blood bank to bring blood products, commandeer the ultrasound, and request the pharmacy to bring needed medication(s). You may pre-notify your closest trauma hospital and transport team to expedite transfer after stabilization. As time allows, use the bathroom before patient arrival.

Case Continuation

As the patient is carried onto the room stretcher and blood drips from his clothes, you notice a slight sense of mental turbulence and a racing heart. But, you calm your mind and focusing on creating a calm and safe environment. You ask the team to dawn protective gear. Before starting your primary exam, you surmise he appears “sick”. You are not yet sure which of the pre-established trauma transfer criteria he may meet, but you suspect he will benefit from continuing care at a trauma hospital…

In the second part, we will continue with focused clinical care steps for trauma resuscitation in the non-trauma center, expediting transfer, and recommendations for process improvement.

References / Further Reading:

- Newgard CD,McConnell KJ, Hedges JR, et al. The benefit of higher level of care transfer of injured patients from nontertiary hospital emergency departments. J Trauma. 2007 Nov;63(5):965-71.

- Garwe T, Cowan LD, Neas B, et al. Survival benefit of transfer to tertiary trauma centers for major trauma patients initially presenting to nontertiary trauma centers. Acad Emerg Med.2010 Nov;17(11):1223-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00918.x.

- Oyentunji T, Haider A, Downing S: Treatment outcomes of injured children at adult level 1 trauma centers: are there benefits from added specialized care? Am J Surg 201: 445, 2011. [PMID: 21421097]

- Junkins EP Jr, McConnell KJ, Mann NC: Pediatric trauma systems in the United States: do they make a difference? Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 7: 76, 2006.

- Osler TM, Vane DW, Tepas JJ, et al. Do pediatric trauma centers have better survival rates than adult trauma centers? An examination of the National Pediatric Trauma Registry. J Trauma 50: 96, 2001. [PMID: 11231677]

- Interfacility Transfer of Injured Patients: Guidelines for Rural Communities. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/publications/ruralguidelines.ashx. Accessed August 25, 2017.

- Marcin JP, Pollack MM: Triage scoring systems, severity of illness measures, and mortality prediction models in pediatric trauma. Crit Care Med 30: S457, 2002. [PMID: 12528788]

- Grossman D. Christensen LW. On Combat, The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace. 3rd Killology Research Group, LLC; 2012.

- https://emcrit.org/emcrit/emcrit-book-club-on-combat-by-grossman/. Accessed August 28, 2017.

- Riskin A,Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. Rudeness and Medical Team Performance. 2017 Feb;139(2). pii: e20162305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2305. Epub 2017 Jan 10.

- http://www.wikem.org/wiki/Needle_cricothyrotomy. Accessed August 15, 2017.

Image Credit

One thought on “Damage Control Resuscitation at the Non-Trauma Center – Part 1: Personal and Team Preparation”