Complications of Varicose Veins: ED Presentations, Evaluation, and Management

- Aug 12th, 2019

- Frances Rusnack

- categories:

Authors: Frances Rusnack, DO (EM Resident Physician, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Roosevelt) and Chen He (EM Attending Physician/Residency Director, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Roosevelt) // Edited by: Erica Simon, MD, MPH, MHA (@E_M_Simon); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 58-year-old female, with a previous medical history of varicose veins, presents to the emergency department with significant bleeding from her right lower extremity. The patient reports scratching her right ankle before falling asleep in bed, waking two hours later to use the restroom, and finding her sheets covered in blood. With the help of her spouse, she quickly wrapped her leg with gauze and sought treatment.

Vitals: BP 132/80, HR 98, RR 16, 37°C, SpO2 99% RA. The patient is anxious. A blood-stained bandage remains wrapped around her right ankle. Upon removal of the bandage, you note a gush of non-pulsatile blood from the distal aspect of a varicose vein, overlying the lateral malleolus.

What are the next steps in your evaluation and treatment?

Background

Varicose veins are often discussed under the larger topic of venous insufficiency. By definition, varicose veins are dilated tortuous veins of the superficial vein network that develop from valvular insufficiency caused by either reflux, obstruction, or a combination of both.1 Varicose veins are differentiated from other venous pathology, such as telangiectasias, by their diameter of at least 3 mm.2 Most are caused by primary venous disease from structural vein wall weakness and/or valve incompetence.3 Other etiologies include deep venous thrombosis (DVT), superficial venous thrombosis (SVT), arteriovenous fistulas, or congenital venous malformations.3 Approximately 23% of adults in the U.S. will experience a varicose vein throughout their lifetime.2 Risk factors include female sex, multiparity, obesity, prolonged standing, thrombotic disease, low levels of physical activity, cigarette smoking, and height (tall height is associated with venous hypertension).2-5

Evaluation

Complaints associated with varicose veins include lower extremity swelling, heaviness, aching, cramping, burning, throbbing, or pruritis.2,5 Patients may also experience pain with direct palpation of the varicose vein.2 Symptoms are commonly relieved upon elevation of the legs.4,5

When assessing a patient who reports extremity pain attributed to varicose veins, differential diagnoses should include:4,5

- Aching sensation in the leg: lumbar radiculopathy, osteoarthritis of the hip/knee

- Posterior knee pain: Baker cyst

- Intermittent claudication: arterial insufficiency

- Focal vessel dilation: arterial aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula

- Calf pain: DVT

- Superficial, tender palpable cord: SVT

Pertinent Examination Findings3,5

Baker cyst: May be associated with a knee effusion and/or decreased range of motion of the knee.

Arterial aneurysm: Pulsatile vascular structure commonly localized to the femoral and popliteal arteries.

Arteriovenous fistula: Pulsations evident upon palpation +/- an audible bruit. (Note: Requires a thorough HPI: may be congenital or the result of trauma/surgery).

Laboratory studies3,5

If a patient reports a history of DVT, or his/her presentation is consistent with a DVT, a complete blood count (CBC) and coagulation panel are advised. A coagulation panel is recommended for anticoagulated patients, and patients with bleeding dyscrasias. In addition to a CBC, individuals who are hemodynamically unstable secondary to blood loss require type and screen/cross.

Imaging3,5

Duplex venous ultrasound may be utilized to evaluate and diagnose a DVT, SVT, Baker cyst, arterial aneurysm, or arteriovenous fistula.5

Varicose Veins Complications

Bleeding

Bleeding may result from trauma to the skin overlying a varicosity, or may occur secondary to spontaneous rupture of the varicosity (e.g. chronic ulceration resulting in tunica erosion).7-9 Although a low-pressure system, prolonged bleeding from a varicose vein may result in hemorrhagic shock and death.10,11 Deaths resulting from varicosity bleeds in the U.S. and UK are most frequently noted among elderly individuals living at home alone.10-13 Risk factors for significant bleeding include advanced age (increased incidence of varicose veins; friable skin), alcohol ingestion (impaired hemostasis), sedative consumption (inability to provide adequate prehospital care), anticoagulation, and treatment non-compliance (failure to elevate the lower extremities, failure to don compression stockings, etc.).11

Mechanisms for Obtaining Hemostasis

Emergency providers (EPs) should quickly assess the bleeding site in an attempt to differentiate arterial from venous bleeding.9 Initial treatment includes the application of direct pressure.12 A pressure dressing may be required.13 If bleeding continues, the addition of topical hemostatic agents, such as tranexamic acid (TXA) may be considered. Case reports cite the successful employment of TXA soaked gauze and TXA paste for cessation of superficial bleeding secondary to minor lacerations, dental extractions, and epistaxis.13,14 Scott Dietrich, an ED Clinical Pharmacist, offers a recipe for a TXA paste with which his organization has had success: three 650 mg TXA tablets crushed into a powder, combined with small amounts of sterile water, and applied to the wound for twenty minutes.15 A discussion of TXA for hemostasis can be found in Dietrich’s article published by Academic Life in Emergency Medicine.

If bleeding continues despite direct pressure and the use of a hemostatic agent, a figure-of-eight suture may be attempted. A detailed video of this technique can be seen at EM:RAP.16

There is limited evidence supporting the use of the figure-of-eight suture for the control of varicose vein bleeds in the ED setting. In 2007, Labas and Cambal performed a retrospective review of 124 patients presenting to the ED with lower extremity varicosity bleeds.17 Of the 124 patients, 72 received compression sclerotherapy, and 52 were treated with cross-stitch compression (the figure-of-eight suture). Among patients who received sutures to attain hemostasis, average healing time was longer (14 vs. 7 days), and 12 experienced a re-bleed (recurrence of bleeding did not occur in the sclerotherapy group).17 Uncontrolled bleeding from varicose veins may ultimately result in hemodynamic instability. Vascular surgery should be consulted.

For stable patients in whom hemostasis is achieved, ED monitoring for the recurrence of bleeding may be considered. Upon discharge, the patient should be directed to his/her primary care physician and vascular surgery for continued care.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

The pathophysiology of varicose veins includes stasis and increased inflammatory and prothrombotic markers: factors which may pre-dispose to deep venous thromboses.18 In 2000, Heit and colleagues performed a population-based, nested, case-control study of 625 patients diagnosed with a first-time venous thromboembolism. After matching for age, sex, calendar year, and medical record number, the authors discovered an association between varicose veins and risk of DVT that diminished with age (age 45 years: OR 4.2; 95% CI 1.6-11.3; age 60 years: OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.0-3.6; age 75 years: OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.0-0.7).18

In order to investigate this reported association, Chang, et al. performed a retrospective cohort study of 425,968 Taiwanese adults to determine the incidence of DVT, PE, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) among patients with and without varicose veins. The authors discovered that individuals with varicose veins had a higher incidence rate of DVT (6.55 vs. 1.23 per 1000 person-years; ARD 5.32; 95% CI 5.8-5.46) and PE (0.48 vs 0.28 per 1000 person-years; ARD 0.20; 95% CI 0.16-0.24).19

Further investigations are required to evaluate these associations for causality. EPs should be aware of current data and assess patients with varicose veins who present with signs and symptoms of DVT and/or PE appropriately. Additional information regarding DVT and PE management can be found at www.emdocs.net/em3am-dvtand http://www.emdocs.net/outpatient-pe-management-controversies-pearls-pitfalls/.

Superficial Venous Thrombosis (SVT)

SVT is inflammation of the superficial veins associated with thrombosis.20, 21 Risk factors include pregnancy, hormonal therapy, history of venous thromboembolism, prolonged immobilization, recent surgery, trauma (recent intravenous cannulation), malignancy (migratory SVT), sclerotherapy, and varicose veins (estimated 70%-88% of patients presenting with SVT have varicose veins).22-24 Patients most commonly present with a hot, painful, palpable cord in the course of a superficial vein.20,22 A thorough HPI and examination are required as the differential diagnosis for SVT includes: cellulitis, erythema nodosum, local reaction secondary to insect bite/sting, and lymphangitis.22

Untreated SVT has been associated with DVT and PE.22,24,25 In patients with SVT the incidence of DVT has been reported as 6%-40%.25 A DVT may occur at a non-contiguous site, or result from direct extension of clot from the superficial to deep venous system at the saphenofemoral junction, saphenopopliteal junction, or perforating veins.24 Current studies estimate that 2%-13% of patients with SVT experience a symptomatic PE.25

Diagnosis of SVT is based upon clinical examintion.22 Ultrasound may be utilized to assess the extent of SVT; providing vital information regarding proximity to the saphenofemoral and saphenopopliteal junctions, and presence or absence of a coexisting DVT.26 Uncomplicated SVT (< 5cm (length) thrombus depicted on US or IV infusion thrombophlebitis) is commonly treated with supportive care: warm compresses, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and elevation of the lower extremities.27 The most recent guideline published by the American College of Chest Physicians recommends treating complicated SVT of the lower limb of (clot length ≥5 cm) with prophylactic dose fondaparinux (2.5 mg daily) or low molecular weight heparin for 45 days to reduce the incidence of DVT/PE or SVT extension (Grade 2B: weak recommendation based upon moderate-quality evidence).27 Vascular surgery should be consulted regarding therapeutic anticoagulation for SVT within 3 cm of the saphenofemoral junction given the proximity to the deep venous system.27

Venous Stasis Ulcers

Risk factors for the development of venous stasis ulcers include varicose veins, chronic venous insufficiency, DVT, obesity, and local trauma.28 The vast majority (90%) of venous stasis ulcers occur around the malleoli.28 In addressing patients with venous stasis ulcers, EPs must evaluate for the presence/absence of cellulitis. Grey, Harding, and Enoch offer a helpful tool in their BMJ publication:28

Management of venous ulcers includes evaluation for infection, patient education, basic wound care, and compression stockings (if no evidence of concomitant arterial insufficiency).1,29 Instruct patients to elevate legs to the level of the heart or above for 30 minutes, 3-4 times a day, and promote light exercise such as walking or ankle mobility.1,15 Oral antibiotics (a broad spectrum penicillin, macrolide, or fluoroquinolone) should be prescribed in the setting of cellulitis. Common pathogens include: pseudomonas, b-hemolytic streptococci, and staph aureus.28

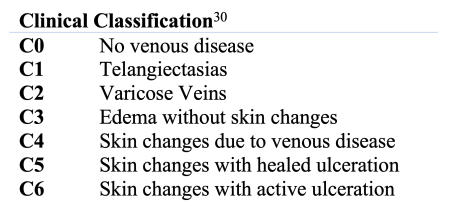

The clinical, etiologic, anatomical, and pathophysiological (CEAP) classification system may be utilized to facilitate provider communication.29 A diagnosis of chronic venous insufficiency is reserved for CEAP classes C4 to C6, and can be applied to patients with varicose veins following the development of superficial skin changes (appearance of brown pigmentation secondary to hemosiderin-laden macrophages).30

Patients should be referred to their primary care physician and vascular surgery.

Key Points

- Varicose veins are common in the elderly. Risk factors include obesity, pregnancy, bleeding dyscrasias, prolonged standing, immobility, and cigarette smoking.

- Complications associated with varicose veins include bleeding, DVT/PE, SVT, and venous ulceration.

- Bleeding may be managed with direct pressure, pressure dressings, topical TXA, a figure-of-eight suture, and vascular surgery consultation.

- Varicose veins are associated with DVT: US evaluation is warranted.

- US may be utilized to evaluate the extent of SVT; proximity to the deep venous system may dictate systemic anticoagulation.

- Both SVT and venous ulceration require evaluation for cellulitis.

Case Resolution

As direct pressure alone failed to control the patient’s bleeding varicose vein, TXA-soaked gauze was applied. After nearly 20 minutes the bleeding slowed to an ooze. A figure-of-eight suture was placed, and complete hemostasis was achieved. Initial CBC was within normal limits. The patient remained hemodynamically stable throughout her ED course. She was discharged to home with primary care physician and vascular surgery follow-up the next day.

References / Further Reading:

- Raju S, Neglén P. Chronic Venous Insufficiency and Varicose Veins. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(22):2319-2327. doi:10.1056/nejmcp0802444.

- Hamdan A. Management of Varicose Veins and Venous Insufficiency. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(24):2612. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.111352.

- Glovickzi P, et al. The Care of Patients with Varicose Veins and Associated Chronic Venous Disease: Clinical Practice Guideline of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2011; 53(16S):2S-48S.

- MacKay D. Hemorrhoids and Varicose Veins: A Review of Treatment Options. Alternative Medicine Review. 2001; 6(2):126-140.

- Dye L. Varicose Veins. Elsevier Point of Care Clinical Overview. 2018.

- Cadman, Bethany. “10 Home Remedies for Varicose Veins.” Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321703.php.

- Wigle RL, Anderson GV. Exsanguinating hemorrhage from peripheral varicosities. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1988;17(1):80-82. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80511-0.

- Serra R, Ielapi N, Bevacqua E, et al. Haemorrhage from varicose veins and varicose ulceration: A systematic review. International Wound Journal. 2018;15(5):829-833. doi:10.1111/iwj.12934.

- Hejna P. A Case of Fatal Spontaneous Varicose Vein Rupture-An Example of Incorrect First Aid. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2009;54(5):1146-1148. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01101.x.

- Fragkouli K, Mitselou A, Boumba VA, Siozios G, Vougiouklakis GT, Vougiouklakis T. Unusual death due to a bleeding from a varicose vein: a case report. BMC Research Notes. 2012;5(1):488. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-5-488.

- Byard RW, Gilbert JD. The Incidence and Characteristic Features of Fatal Hemorrhage Due to Ruptured Varicose Veins. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2007;28(4):299-302. doi:10.1097/paf.0b013e31814250b3.

- Cocker D, Nyamekye I. Fatal haemorrhage from varicose veins: is the correct advice being given? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2008;101(10):515-516. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2008.080132.

- Mason J. Hemostatic Pressure Dressing. EM:RAP. https://www.emrap.org/episode/hemostatic/hemostatic. Accessed March 16, 2019.

- Noble S, Chitnis J. Case report: use of topical tranexamic acid to stop localized bleeding. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2012;30(6):509-510. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201684.

- Dietrich S. Trick of the Trade: Topical Tranexamic Acid Paste for Hemostasis. Academic Life in Emergency Medicine. https://www.aliem.com/2016/02/trick-trade-topical-tranexamic-acid-paste-hemostasis.Published November 12, 2016. Accessed March 16, 2019.

- Mason J. Figure of 8 Suture. EM:RAP. https://www.emrap.org/episode/figureof8suture. Accessed March 16, 2019.

- Labas P, Cambal M. Profuse Bleeding in Patients with Chronic Venous Insufficiency. International Angiology. 2007;26(1):65-66

- Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, Ofallon WM, Melton LJ. Risk Factors for Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(6):809. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.6.809.

- Chang S-L, Huang Y-L, Lee M-C, et al. Association of Varicose Veins With Incident Venous Thromboembolism and Peripheral Artery Disease. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;319(8):807. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0246.

- Nasr H, Scriven JM. Superficial thrombophlebitis (superficial venous thrombosis). Bmj. 2015;350(jun22 6). doi:10.1136/bmj.h2039.

- Evans NS, Ratchford EV. Superficial vein thrombosis. Vascular Medicine. 2018;23(2):187-189. doi:10.1177/1358863×18755928.

- Decousus H, Quere I, Presles E. Superficial Venous Thrombosis and Venous Thromboembolism A Large, Prospective Epidemiologic Study. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2010;52(6):1727-1728. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.084.

- Lutter K, Kerr T, Roedersheimer L, et al. Superficial thrombophlebitis diagnosed by duplex scanning. Surgery. 1991; 110:42-46.

- Galanaud J-P, Sevestre M-A, Pernod G, et al. Long-term risk of venous thromboembolism recurrence after isolated superficial vein thrombosis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2017;15(6):1123-1131. doi:10.1111/jth.13679.

- Litzendorf M, Satiani B. Superficial venous thrombosis: disease progression and evolving treatment approaches. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011; 7:569-575.

- Cosmi B. Management of superficial vein thrombosis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2015;13(7):1175-1183. doi:10.1111/jth.12986.

- Kearon C. Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. CHEST. 2012;141(2):e419S-e494S.

- Grey J, Harding K, Enoch S. ABC of wound healing: venous and arterial leg ulcers. BMJ. 2006; 332(7537):347-350.

- Nisio MD, Wichers IM, Middeldorp S. Treatment for superficial thrombophlebitis of the leg. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004982.pub6.

- Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PDC, Nicolaides AN, Boisseau MR, Eklof B. Chronic Venous Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(5):488-498. doi:10.1056/nejmra055289.

- Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Venous Ulcers. American Family Physician. 2010;81(8):989-996.

One thought on “Complications of Varicose Veins: ED Presentations, Evaluation, and Management”