EM@3AM: Erysipelas

- Jul 15th, 2023

- Mounir Contreras Cejin

- categories:

Authors: Mounir Contreras Cejin, MD (EM Resident Physician, UT Southwestern – Dallas, TX); Felipe Gonzalez Gutierrez (Medical Student, UT Southwestern – Dallas, TX); Joshua Kern, MD (Assistant Professor of EM/Attending Physician, UT Southwestern – Dallas, TX) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 65-year-old female with a history of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, chronic lymphedema and venous insufficiency presents to the ED with redness to her right leg noted 2 days ago but worsening since yesterday. She has had pruritus and swelling to the site accompanied by a painful burning sensation and a couple “painful knots” on her right inguinal region. She denies any prior history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT, IV drug use, or any history of vascular surgeries to the lower extremities. She has also had malaise for a few days and says that the redness has markedly increased since yesterday.

Vital signs are unremarkable. On examination of the right lower extremity there is a large area of intense erythema with sharply demarcated borders that appears raised with some swelling and mild tenderness to palpation. There are hyperpigmentation changes to the bilateral ankles consistent with the patient’s history of venous insufficiency; upon inspection, there is an ulcer to the medial aspect of the right ankle. Her joints are nontender and have full range of motion. No fungal infections are identified on the feet.

Given the patient’s comorbidities laboratory and imaging studies are ordered. A lower extremity radiograph does not reveal any gas formation and an ultrasound of the lower extremity is negative for DVT or cobblestoning, WBC is within normal limits and there are mild elevations in ESR and CRP.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Answer: Erysipelas

Introduction/Etiology

- Erysipelas is a superficial infection of the dermis that may extend to the superficial cutaneous lymphatics3, 6, 10

- Described as an area of sharply demarcated erythema with raised edges that most commonly affects the lower extremities (approximately 80% of cases) and face3, 5, 6, 10

- Streptococcus pyogenes is the most commonly implicated organism1, 5, 6

- Other organisms that have been reported but are rare include S. aureus(including MRSA), Klebsiella pneumoniae, influenzae, E. coli, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, and Moraxella species

- Infection often occurs from disruption of the skin1, 5, 10

- Erysipelas may extend via the lymphatic system, which explains why some patients have tender inguinal lymphadenopathy proximal to the affected leg

- Complications include thrombophlebitis, abscesses, and gangrene6

- Risk factors include lymphedema, obesity, leg ulcers, IV drug abuse, tinea pedis (from skin breakdown in the intertriginous space), poorly controlled diabetes (or other immunocompromised states), liver disease, nephrotic syndrome, AV fistulas, saphenous vein excision for bypass or radical mastectomy (i.e., due to lymphatic obstruction)3, 5

Epidemiology

- Erysipelas can affect people of all age groups, races, and sex5

- Some studies showed that erysipelas is more common in females

- Peak incidence is reported to be in patients aged 60 to 80 years

- The incidence and prevalence of erysipelas has decreased with improved sanitation and the development of antibiotics, respectively 5

ED Evaluation

- Erysipelas is a clinical diagnosis and most cases do not require laboratory or imaging studies5, 10

History and Physical

- Timing of symptoms and speed of progression3, 5, 6, 9

- Assess comorbidities3, 5, 6, 9

- Thorough exam looking for areas of skin breakdown that could account for a portal of entry

- Assess the intertriginous areas of the toes for tenia pedis with skin breakdown1

Differential Diagnosis

- Consider the following: necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, clostridial myonecrosis, pyomyositis, compartment syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, cellulitis9

- Red-flags include severe sepsis, septic shock, pain that is out of proportion to exam and a rapidly progressing infection

- Always consider a more extensive work up in any ill-appearing patient (e.g., sepsis), immunocompromised patients, IV drug users, patients with prosthetic heart valves or any intravascular device

- Clinical features may not abe enough to differentiate erysipelas from cellulitis, and in such cases the treatment should be targeted towards cellulitis

Labs

- No laboratory evaluation is required for the diagnosis of erysipelas. Labs are not necessary for otherwise healthy individuals without systemic symptoms ,as they do not change management3, 5

- Labs may show an elevated WBC, ESR, and CRP

- Blood cultures have a low yield (only positive in 5% of cases) but should be considered in those with prosthetic heart valves, artificial joints, and immunocompromised or toxic-appearing patients3, 5

Imaging

- Imaging not usually indicated3

- May assist in identifying other causes when these are suspected (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis)3, 11

- Imaging is usually in the form of plain film X-rays, CT scans, ultrasound, or MRI and depend on the suspected pathology

- Ultrasound can be of utility when the diagnosis is in question as it may provide evidence of infections that affect deeper tissues (e.g., cobblestoning in cellulitis)11

Treatment

- Most cases of erysipelas resolve without sequelae after appropriate antibiotic therapy.3, 9 The following are general recommendations for adult patients with normal renal function and may differ from local guidelines

- Some experts believe that when erysipelas affects the face covering for MRSA is indicated and that in cases where it affects the legs a penicillin or cephalosporin is sufficient11

- The following are indications for MRSA coverage 9

- Systemic signs of toxicity (fevers, tachycardia, hypotension)

- Purulent drainage or exudate

- Immunocompromised states (e.g., immunosuppressive drugs, chemotherapy)

- Risk factors for MRSA infection (past infection, MRSA colonization, intravenous drug use, or recent healthcare exposure)

- Parenteral antibiotics covering for both beta-hemolytic streptococcus and S. aureus including MRSA should be given in any patient who has systemic symptoms, including the following:1, 5, 9, 12

- Fever greater than 100.4°F/38°C

- Hypotension

- Sustained tachycardia

- Rapid progression of erythema (i.e., doubling of affected area within 24 hours)

- Extensive erythema

- Immunocompromised state

- Inability to tolerate or absorb oral therapy

- The treatment for patients requiring parenteral antibiotics is the same as for cellulitis

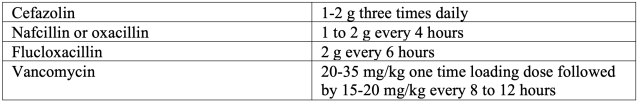

Antibiotic therapy1, 3, 9, 12

- Oral antibiotics that cover beta-hemolytic streptococcus

- Oral antibiotics that cover beta-hemolytic streptococcus and MRSA

- Can be used in cases of beta-lactam allergy

- Another appropriate regimen used when MRSA is suspected is amoxicillin 875 mg orally twice daily (streptococcal coverage) plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily (staphylococcal coverage including MRSA). However, this regimen is not to be used in patients with beta lactam allergies

- Parenteral antibiotics that cover beta-hemolytic streptococcus and MSSA

- Parenteral antibiotics that cover beta-hemolytic streptococcus and MRSA

- In recent years the FDA has also approved 3 antibiotics for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, including oritavancin(Orbactiv), dalbavancin (Dalvance), and tedizolid (Sivextro)3

- These agents cover MSSA, MRSA, S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, among others

- Duration of antibiotic therapy is analogous to that of cellulitis. In general, 5 to 7 days is appropriate for uncomplicated cases. Extension of antibiotic therapy for up to 14 days may be needed in the setting of severe infection, slow response, or immunosuppression9

- Symptomatic improvement is usually seen in 24 to 48 hours but visible improvement in skin manifestation can take 72 hours

- Adjunctive treatments include cold compresses, analgesics, and elevation of the affected limb5, 6, 9

- Tinea pedis may cause skin breaks that becomes a site of entry. 1 These require topical antifungal treatment in addition to the appropriate antibiotic regimen that covers for erysipelas. Oral or IV antifungals are seldom indicated 6

- Topical terbinafine or imidazole two times daily for 2-3 weeks4

- Absorbent antifungal powder containing aluminum chloride4

- Always keep the areas dry and avoid tight fitting clothing4

- Surgical consultation for debridement if there is gangrenous or necrotic tissue5, 6

Case Resolution

The patient received appropriate parenteral antibiotics with great response. The patient reported feeling better, pain and other symptoms were well controlled 24 hours after starting antibiotics and pain medication. The infection began to subside 72 hours after starting therapy. During her admission, an MRI was ordered and was negative for osteomyelitis. Cultures did not grow any organisms. Wound care was consulted for management of her ulcer. The patient was subsequently discharged home and had made marked improvement on subsequent follow up.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Erysipelas is a superficial infection that most commonly affects the lower extremities and is often caused by Group A Streptococcus infection

- Laboratory work up is often not necessary and does not change management in otherwise healthy patients. However, it must be considered in toxic-appearing patients, those with prosthetic heart valves, artificial joints, or immunocompromised states

- Clinicians must keep a broad differential and consider other conditions such as necrotizing fasciitis, clostridial myonecrosis, compartment syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, etc.

- Always inspect the feet for evidence of fungal infections as these may cause skin breakdown that could be the primary portal of entry

- Choose parenteral antibiotics for those with systemic symptoms, rapid progression of erythema, immunocompromised states or inability to tolerate oral therapy

A 70-year-old woman presents to the emergency department for a rash on her arm beginning this morning. She notes increasing redness on her right arm with some associated pain and swelling. She also reports generalized malaise and chills in the 24 hours preceding the onset of the rash. She reports no recent contacts with similar symptoms and has never had symptoms like this in the past. Her medical history includes type 2 diabetes, for which she takes metformin. Which of the following examination findings would suggest a diagnosis of erysipelas in this patient?

A) Annular shape with central clearing

B) Distinct border and associated fever

C) Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base

D) Poorly demarcated border

E) Purulent drainage

Answer: B

Erysipelas is a cutaneous disorder caused by bacterial infection of the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics, most commonly due to beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species. It is most frequently seen in young children and older adult patients, but it can affect any age group. Because there may be significant overlap in clinical presentation between erysipelas and other cutaneous disorders, both infectious and noninfectious, understanding of the characteristic signs and symptoms aids in making an accurate diagnosis and, thus, initiating appropriate treatment.

Patients with erysipelas generally report acute onset of a prodrome of systemic symptoms, including fever, malaise, and headache. This often begins in the minutes to hours preceding the development of local inflammatory symptoms. Physical examination findings of erysipelas are nearly always unilateral and include local erythema, edema, and warmth. The erythema typically has a characteristically distinct border, while that of cellulitis is much more poorly demarcated. The border may be raised, but erysipelas does not cause overt superficial skin lesions that other infectious rashes might cause (e.g., vesicular lesions in herpes simplex virus infection). Erysipelas is characteristically nonpurulent, and lymphangitis and regional lymphadenopathy may be present, but these often occur in cellulitis as well.

Treatment of erysipelas consists of oral antibiotics, with coverage of both beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Commonly used drugs for this purpose include cephalexin, dicloxacillin, and clindamycin. If the presentation cannot be clinically distinguished from cellulitis and there is suspicion of potential methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, coverage of such would be indicated.

An annular rash with central clearing (A) describes the typical appearance of ringworm (tinea corporis), which is a cutaneous fungal infection. Herpes simplex virus causes a rash appearing as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base (C), and this description is not consistent with erysipelas. How well or poorly demarcated the border of the erythema is in cases of cellulitis and erysipelas is often used to help differentiate between the two. A poorly demarcated border (D) is much more consistent with cellulitis. Purulent drainage (E) is possible with many infections, including cutaneous abscesses and cellulitis, but is not typical of erysipelas.